1. Overview of the development of Russian art

In the period under review, Russian art developed in its own distinctive direction, connecting the Byzantine heritage and creatively transformed borrowings from classicism (mainly Italian). Churches, monasteries, and to a lesser extent secular houses are performed in a characteristic national style. Painting is represented mainly by icons in the Byzantine style and frescoes, the manner of which by the end of the century developed in the direction of realism.

Russian studies of recent decades have successfully tried to highlight with bright light the later departments of national Russian art, the only surviving daughter of Byzantine art. In addition to the history of Novitsky art and individual articles by various scholars, for the XVII century especially important are the “Monuments of ancient Russian architecture” Suslova and “Materials on the history of Russian iconography” by Likhachev. Since, however, the significance of the Russian art of those times was limited to the land of the kings, we are satisfied here with brief instructions.

In the flourishing Russian church architecture of the 17th century, we meet, in a variety of ways and often mixed with each other, mainly two main types that emerged side by side in the 16th century: the five-dome church type, whose brilliant onion domes, often numerous, rise above the roof cylindrical neck-like towers, then on the surfaces in the form of obelisks, and the type of pyramidal church, surrounded by verandas and covered stairways, but also usually crowned with small onion domes. The octagonal pyramidal belltowers were often placed next to five-domed churches, but often also connected with them into one inseparable whole. Ancient wooden Russian style responds mainly in more simple pyramidal churches; in some areas of the empire of the kings, especially in the far north, and now there is no shortage of real wooden churches that preserve the style in the original purity, and precisely because of seemingly translations from Old Norse. Characteristic, for example, is the wooden church in Umba on the White Sea, with its piled roofs one above the other and connecting the entire octagonal middle pyramid, topped with a bulbous dome. There is no hint of an Italian renaissance.

The Italian Renaissance and the international Baroque style, even in the Russian stone churches of this era, respond only slightly, fragmentary and in distorted versions. The example given by the Archangel Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin with its capitals in the style of a pure early Renaissance, did not find any imitators. Simple round columns and pilasters, which make an impression of Tuscan from a distance, sometimes carry flat tops, which are a cross between Doric and Romanesque capitals. Corinthian memories appear in more pure forms. Closely contiguous pillars of railings and slender round columns are connected by wide belts. Numerous, luxuriously decorated exterior window frames are crowned with keel-shaped arches more often than with triangular gables. On the entrance portals, no less richly framed, round and flat arches often alternate with keel-shaped. Some of the special nature of the roofs are due to the attic, mostly keeled elongated, false extensions, which they exactly seated. Becoming smaller in the upper rows, these decorations connect the edge of the roof with domed towers. Empty wall squares do not like. Sometimes the walls are completely covered with faceted or even cassette quadrangles. The railing of the verandas, porches or galleries rarely consist of separate pillars; for the most part these are solid walls, decorated on the outside with quadrangular cassettes arranged in a row to the height of the wall. Among the abundant, diverse, individual forms of this style, ancient geometric patterns, zigzags, stripes, and scales can be seen here and there. Compared with the Russian style of medieval cathedrals, this whole type of building and decoration can be designated by the name of the national Russian baroque.

Fig. 197. Church of the Resurrection in Kostroma. According to V. Suslov

In Moscow, there is the so-called “Red Church” of the Dormition of the Virgin, a famous example of the most luxurious combination of onion-dome and pyramid-tower systems, and at the same time with extremely clear Italian influences, with the walls divided into columns in the style of Corinthian and baroque window frames. The more clean bulbous-domed style is the Moscow Church of the Nativity of the Virgin in Putinki, whose simple lower floor gives the impression of a corinth, and all the beauty described earlier is scattered in the upper floor. In the Rostov Kremlin there are five churches of the XVII century. The Church of the Resurrection and the Church of St. John the Wonderworker have high, richly dissected facades, decorated on the front facade with medieval round towers, and at the top end like real five-domed churches. The Church of the Resurrection in Romanov-Borisoglebsk near Rostov (1652) is a five-domed church with a clearly expressed two-storeyed verandah with semi-circular arcades that correspond to semi-circular painted fields under the main roof, and the necks of bulbous domes are divided by keel-shaped fake arcades. With a similar arrangement, the Church of the Resurrection in Kostroma (1650) has, without exception, semi-circular openings and faceted walls. The church of the Kazan Mother of God in Murom (1648) is especially richly dissected, and it is equipped with two pyramidal towers. Frames here are found to be semi-circular, keeled with triangular gables, one of which is torn apart, as in the Western Baroque style. The frames of the windows of the Church of the Kazan Mother of God in Markov look completely Russian. An example of the 17th century Russian church with flat domes and flat zakomara can serve as the Archangel church of the Makaryevsky monastery in Zheltovodsk.

Fig. 198. Framing the window of the Church of the Kazan Mother of God in Markov. According to V. Suslov

Among the Russian houses of this time, first of all, the present building of the Belvedere or Terem Palace in Moscow located around the pentagonal courtyard should be called five stepped, gradually decreasing floors, the dismemberment of which from afar, but only from afar, reminds Italianizing late Renaissance. A particularly interesting Russian private house of this time, a stone building with (restored) wooden extensions - the house of Zelejshchikov in Cheboksary, Kazan province. Opened by two arched spans, the middle ledge, in which a staircase goes up, is crowned in front of the roof by a huge wooden keel-shaped gauge. Finally, we should not forget about the Sukharev Tower in Moscow, erected in 1689 by Peter the Great. Compared with Ivan the Great, who was completed in 1660, whose “bride” the Russian people call her, she already produces a much more European impression on her skeleton. It is one of the last architectural works of the “Moscow” period of the empire of kings. The founding of Petersburg (1703) begins the Petersburg period of Russia, which deliberately turns its face to the West.

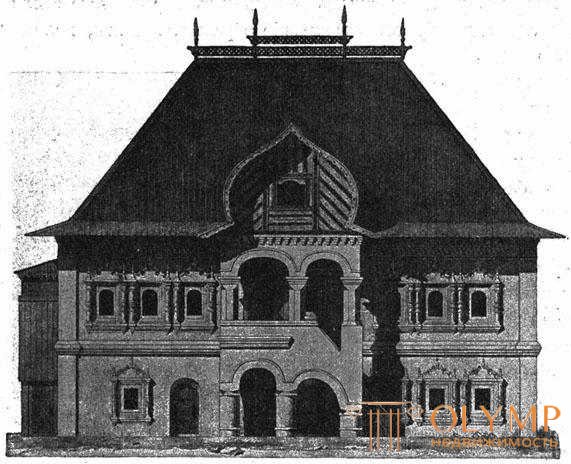

Fig. 199. House Zelejshchikov in Cheboksary (Kazan province). According to V. Suslov

About Russian painting of the XVII century, you can talk a lot or a little. We must be content with little. In addition to church frescoes, predominantly on a blue background, always written in ancient solemn Byzantine rhythms with exaggeratedly long figures, images on the boards of church iconostasis, private house icons and miniatures of manuscripts, which are touched by the West with copper and wood, join the Kiev school.

Large series of XVII century frescoes, in which an independent sense of nature and ardent artistic fantasy often struggle with old prescriptions, are preserved in some Moscow, Yaroslavl and Rostov churches. The Archangel Cathedral in Moscow (1680–1681) depicts a series of life-sized kings, in fixed positions, above their tombs, but there is also an image of the Last Judgment. The painter of these paintings is one Ermolaev. But Simon Ushakov is considered a real innovator, in which Moscow at the end of the seventeenth century had a master who broke off Byzantine bonds with a powerful sense of life. However, the news available to us about his illustrious works is not enough to make a visual representation of them.

For a review of the Russian iconography of wall paintings and room images, we still do not have reliable strongholds. There is no doubt that in this numbed Byzantine-Russian art further research will reveal the important beginnings of development for various localities and various external influences coming from even Western art.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)