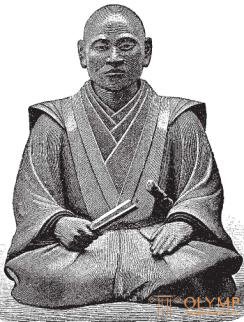

XV century. in Japan, as well as in China and Europe, was a century of rebirth, and the XVI century. brought what was done in the XV, to a brilliant result. This revival on Japanese soil can rightfully be called the Chinese Renaissance. As a healing remedy against the dizziness of the Tosa School, an appeal was made to the renewed animation of Chinese art. But the models for the Japanese painters were no longer the masters of the Ming dynasty, but the great artists of the Song dynasty (960-1279), and more than ever, painting began to set the tone for the further development of all other branches of Japanese art. Of course, the Japanese consider classical and national their own architecture of the 15th and 16th centuries, which little by little endowed the entire empire with castles, temples and palaces. No matter how good the proportions of their appearance are and how luxurious their interior is, we cannot say that architecture takes a further step forward in them. A large wooden Buddha statue in Kyoto shows that a large Buddhist plastic in Japan is now obsolete. Portrait sculpture alone produced something worthy of attention, such as, for example, published by Bing, a beautifully executed, truthful and simple wooden statue-portrait of the great shogun Gideyoshi, the work of the master Katakir (fig. 617). Naturalistic small-scale plastics had just begun to develop, while Seto's potters in Owari and Karatsu provinces in Gitzen province under Yoshimas (died in 1489), the patron of strictly regulated tea societies, which became famous under the name Chanoyu, were already supplying everything new and new varieties of luxuriously decorated dishes, and varnishes achieved such grace relief images and such magnificence of color, with the use of her cinnabar, silver and various inlays, which did not reach then no one. However, at the head of all this development of Japanese art of the 15th and 16th centuries was still painting.

Fig. 617. Shogun Gideyoshi. Wood, the work of Katakiris. By Bing

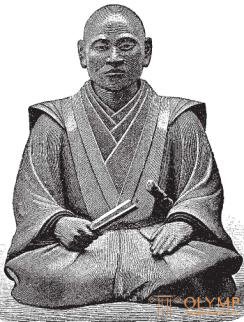

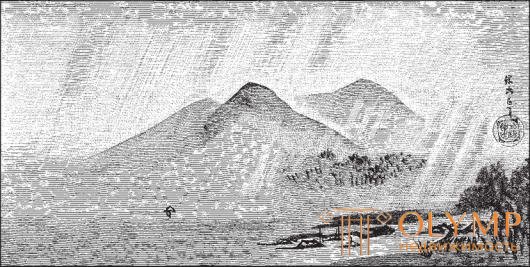

The foremost painters still did not neglect the Buddhist and historical subjects; but, imitating their Chinese predecessors of the Song dynasty, they more and more transferred the center of gravity of their mastery to landscape painting and small images from the world of animals and plants. The preference was given to the Chinese ideal landscape, with rocky mountains rising to the sky, the remoteness of which was indicated preferably by clouds of clouds obscuring them - with waterfalls, rivers and lakes, pagoda towers protruding over the tops of the pines. The change of seasons, causing both moods in poetry and Chinese and Japanese paintings to changeable moods, gave rise to winter, spring and summer landscapes. Small pictures of nature in particular are charming due to the snow depicted in them, under the weight of which trees and bamboo bend, or lush flowers on the bushes and branches, animated by birds fluttering on them. Next to the multi-color painting, Chinese painting received Chinese citizenship in black and white, in which now the Japanese have learned to transmit morning and evening fog, stormy and rainy weather. The images of this kind show a kind of a mixture of fluent, broad impressionistic courage with a learned academic sobriety; In this technique, every movement of the brush was traditional. Whatever enthusiasm the artist turned to nature, he nevertheless wanted to see her just as the Chinese imagined it. And the main founders of this trend in Japanese painting of the 15th century were indeed the visiting Chinese Yosetsu and his student Shiubun.

Fig. 618. Seschia landscape in Chinese style. By gonze

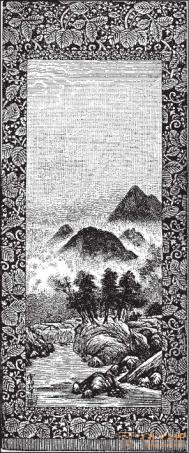

The three great Japanese masters who committed the coup in question were: Meishio (1351-1427), nicknamed Cho Densu, whose picture "The Death of a Buddha" in one of the Kyoto temples resembles the works of the ancient Chinese; Kano Masanobu (born at the beginning, and died at the end of the 15th century), the forefather of the artistic Kano dynasty, whose works, remarkable for their excellent patterns and colors, became very rare in Japan itself, and finally, even more significant than the first two, Sesshio (1414-1506) - the founder of Japanese painting in black and white in large size, the artist, whom Phenolloza considered the central luminary in a whole pleiad of masters. He called it "the open door, through which all others penetrated the seventh sky of Chinese genius, a well, from which all later artists drew the drink of immortality."

Fig. 619. Meishio. Holy with a lion. According to Anderson

The son of Kano, Masanobu Kano Motonobu (1475-1559), working in the style of his father and mainly in the style of Sesshio, founded the famous Kano school, which gave a lot of followers , which since its time has dominated Japanese art along with the Tosa school. While the Tosa school, of which Mitsunobu was then the chief representative , enjoyed the patronage of the Mikado, the Kano school was the shogun’s privileged school. Its head, Kano Motonobu, who painted images of Buddhist saints and Chinese landscapes, is considered the "prince of all Sino-Japanese artists" in the Orthodox history of Japanese art. However, Phenollosa found in him some lack of warmth, freshness and depth. The most outstanding students of the Kano school in the second half of the 16th century were Kano Sanraku and Kano Eytoku. Sanraku wrote mostly folk scenes and, therefore, has already come out of China; with respect to Eytoku Phenollosa, he said that he was perhaps the last great Japanese artist, "whose heart was warmed by internal fire, ignited by the torch of the genius of the Chinese dynasty Song."

Pictures of some of these masters of the XV and XVI centuries were in the European collections; others are known for woodcuts of Japanese work. Phenollosa recognized the landscape of Sesshio, which is in the Bing collection in Paris (Fig. 618), which was published by Gonze, especially characteristic. The Anderson collection in the British Museum has a genuine painting by Meishio (Cho Densu), depicting a saint with his lion in the desert (fig. 619), a whole series of Kakémono by Kano Motonobu, the Chinese landscape Kano Masanobu, part of the painting “Flowers and Birds” by Utanosuke, the moonlight landscape of Kano Sanraku and the allegorical female figure of Kano Eytoku. In the Girke collection in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology, there are works by Sesshia, Kano Motonobu and Kano Sanraku. In the Gonze collection in Paris, a curious image of a daimyo on horseback, belonging to Mitsunobu, the master of the Tosa school (fig. 620).

Fig. 620. Mitsunobu. Daimyo riding a horse. By gonze

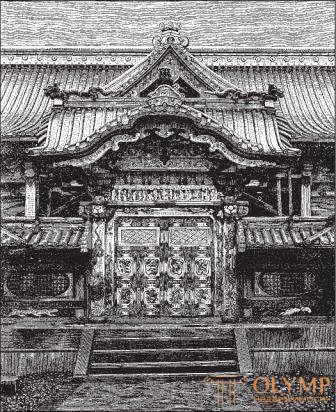

In the 17th century, Japanese art became increasingly bright in its striving for decorativeness, which is most striking to Europeans. It was expressed in architecture, which at Shogun Yemitsu from the house of Tokugawa (1623-1652) had the highest degree of craftsmanship and luxury. Grandfather Iemitsu Ieyasu, the first of the great surname Tokugawa, died in 1616 at the 74th year of life. The temple dedicated to his memory in Nikko, built under his successors by the gifted architects of the time, Cengoro (Iengoro), is usually referred to as the most magnificent and characteristic monument of Japanese architecture. It is located on the mountainside among a wonderful park and consists of a number of terraces, stairs, fences, separate chapels and pagodoo towers. But the magnificent carving with which the roofs of its gates, bent upwards along the bottom edge, as well as the interior of its halls, is especially surprising. The purity of the carpentry of its pillars, beams, planks, struts, as well as the finishing of bronze plating, bronze nails and other metal parts is amazing; at the same time, everything shines in it with strong, bright, but harmonious colors, which make an enchanting impression. On the outer pillars of the main inner gate (Fig. 621) stretch upward, wriggling, the sacred dragons, executed very realistically. Mummy portraits depict mummy trees in lush spring bloom, the branches of which move to the upper timber. Even higher, on the frieze, a multi-figured set of gods is represented; on other architectural parts of the garland of flowers and the plexus of animals interspersed with elegant geometric ornaments. Never before has wooden buildings reached such a perfection as this; never has wood carving produced anything so full of life as, for example, the famous "sleeping cat" in the chapel of the dead of this temple. "Whoever did not see the Tsengoro thread in Nikko, he did not see anything," say the Japanese. The wonders of his art left Zengoro also in Kyoto. On the luxury, diversity and ease of his skill give a complete concept of carved gates and ceiling cassettes in the temple of Nishi Gongwaniyi. At the same time, there are 30 planks with reliefs on the outer wall of the Matsunomori temple in Nagasaki, published by Muller Beck. These are works by Kiushiu, representing scenes of Japanese industrial life, they are distinguished by carefulness and fidelity of drawing and stylish coloring. But Yemitsu was mainly concerned with decorating the temples and palaces of the new capital of the Tokugawa dynasty, Edo (Tokyo). The buildings in Nikko and Kyoto can be considered as the final phenomena in the history of the development of Japanese architecture. The path that she had to walk from the simple hut of the Aino tribe and the simple ancient Shinto sanctuary to the majestic buildings covered with painted carvings in these cities was not short.

Fig. 621. The main gate of the Ieyasu temple at Nikko. According to Anderson

In the transition to the XVIII century. next to the large decorative carvings of wood, a sculpture of small forms was increasingly advanced . Small Japanese bronze items, which are best studied in Paris collections, especially in the museums of Cernuski and Guimet, as well as in the Eder collection in Düsseldorf, depicting people and all kinds of animals, are wonders of art in terms of liveliness of design and fineness; plastic products of various kinds, with which we have already become acquainted, in part, speaking of the so-called netsuke (see fig. 608), also only during the seventeenth century did they gradually acquire the artistic processing by which netsu of the eighteenth century became favorite works of Japanese applied art; the same should be said about swords cups, which we have already spoken of. In the 17th and 18th centuries, all the delightful metal works of famous masters, which are the pride of European collections, were performed. The kinai engraver (a cup with langoustines of his work, shown in Fig. 622, is in the Gonze collection in Paris) worked in the 16th century. Toomioshi and Ieiu, who owns a cup with flowers (fig. 623) in the same meeting, lived already at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Fig. 622. A cup of sword with crayfish. Job Kinai. By gonze

Fig. 623. Sword cup with flowers. Job Iyeu. By gonze

In painting, the great schools of Kano and Tosa produced in the XVII and XVIII centuries many more artists who had received great fame. But upon closer inspection, their fame is exaggerated. The famous landscape painter Tanyu (1600-1674), whose disciples himself identified himself as the shooter Yemitsu, Naonobu (died in 1651) and his son Tsunenobu (died in 1683) in Edo, Sanseцу (died in 1654) ), Sanraku's son-in-law, in Kyoto, is considered the luminaries of the Kano school. An impressionistic, mood-full landscape in the rainy weather by Tanyu, in the collection of Ernest Garth in London, is reproduced in Figure. 624. Mitsuoki (died in 1691), Mitsugoshi (died in 1772) and his son Mitsusada (died in 1806) are considered to adorn the school of Tosa. The works of most of these artists and their contemporaries fell into the European collections; they testify not to the progressive development of these schools, but to their decline. The works of those painters of the 17th century who aspired to free themselves from the oppression of the regulations established by the schools in order to keep the decorative trend of their time, devote themselves to so-called small art, or look at their native Japanese nature and life and pass them on a much deeper impression. in a new way. Among such artists are Sotatsu (he worked around 1670), one of the greatest painters of colors and colorists in Japan, transferred from Kano to Tosa school, his contemporary, Kano Marikagge, distinguished by the art of writing in china, and a student of Soatsu, Korin Ogata (1660-1710), according to Gonze, "is the most Japanese of all Japanese painters," who informed the ornamentation of the character that our time likes so much (Fig. 625). But the new naturalistic trend, which was soon to become famous under the name Ukiyo-e (the school of the sorrow), separated from the school of Tosa, which from the very beginning was committed to national themes. The founder of the new school, Matagei, worked in the middle - XV century. He wrote true, full of life types, groups and scenes from the life of the lower classes of the people. The art dealer Ketchem in New York had in 1896 a wall screen depicting women engaged in music, according to Phenollosa, one of the best works of Mata-gay. Although the oldest masters of the Tosa school, and even Kano schools, such as Kano Sanraku, were the first in this field, Matagei formed an entire school of followers of this trend in Kyoto. His pupil Hasikawa Moronobu, who died in the second decade of the 18th century, is one of the most beloved Japanese artists. Kakmono in the Girke collection in Berlin, which depicts a society about to ride a boat, according to Girke, "is undoubtedly the best of the surviving works of this artist and enjoys great fame in Japan." Hasikawa Moronobu was also engaged in decorative art, writing samples for silk painters and Kyoto embroiderers; his drawings for wood engraving contributed to the improvement of this branch of art. In addition to these artists, as one of the most versatile and significant masters of the time in question, Icho (1651-1724), who belonged to the Kano school and spread Udiyo-e's bold, fresh and colorful style to Edo, should be mentioned. Two emakimono his works are in the collection of Girke; one of them shows miners, the other is a Japanese holiday. In fig. 626 - village scene. All these masters prepared the last period of the magnificent flourishing of Japanese art, which began in the middle of the 18th century. Over a hundred and fifty years (1600-1750), various technical arts, partly with the assistance of these artists, also achieved high development.

Fig. 624. Tanyu. "Rain". According to Anderson

In Japan, chromoxylography is most closely associated with painting , which increasingly gained worldwide fame. Since Phenollosa in 1891 published his detailed scientific catalog of the New York exhibition of Japanese paintings and engravings, and Seidlitz in 1897 wrote a detailed history of Japanese multicolored engravings, this latter has become one of the most important and most famous pieces of art history. Until the beginning of the 17th century, in Japan, for several centuries, books were printed partly with wooden boards, partly with movable wooden or copper type. Similarly, prints on separate sheets have long existed in the Buddhist religious cult. The first Japanese book with woodcuts was printed, apparently, in 1608. But only in the engravings of Hasikawa Moronobu (1646-1714) to a secular book, which appeared in 1682, does the xylographic technique matured to artistic force and clarity . Black and white masses are distributed on his surface of the pattern with the correct understanding of the effect of their opposite; multi-figured compositions differ ancient Japanese stiffness.

Fig. 625. Korin Ogata. Flying ducks. Figure from a Japanese essay. According to Anderson

Fig. 626. Icho. Village scene. By Bing

The pupil Moronobu Okumur Masanobu (died in 1751 or 1752) was a great master in painting, and only in the first period of his activity did the mentor keep. Of the other followers of Moronobu in the field of monochrome black prints - Tahibana Morikuni (1670-1748), the publisher of many illustrated collections for artistic artisans' leadership, engraved on wood with greater dexterity and comprehensive understanding of this case, and Hasikawa Sukenobu (1671-1760; see rice 615), which mostly excelled in portraying the tender beauty of Japanese women, began to work rather casually. It should be noted that the masters of Japanese engraving on wood only invented and painted their compositions, but others cut them. An engraver used to stick a painter’s drawing on thin paper onto a piece of, as a rule, cherry wood and then began to cut it with a sharp knife. The coloring of the printed black ink engravings, which at first, even under Moronobu, was rather scanty, the followers of this master became more complicated and then led to printing with several colors, and again turned to Chinese samples, unfortunately still not fully scientifically researched.

Printing in two colors was introduced in Japan, believed to be in 1743 by Nishimura Shigenaga (died in 1760), depicting scenes of everyday life. In addition to Shigenaga, printing paints subdued the aforementioned Masanobu, the first specialist in tempting images of the beauties of tea houses, and mainly the great Torii Kiyonobu (1688-1755), founder of the Torii school, the first expert in the witty images of Edo actors. The first tricolor woodcutting of Phenollosa was Shigenaga print, printed in 1759 and depicting a residential gallery, but Byng believed that Masanobu had done printing in three colors before. For the oldest two-color woodcuts, a delicate red paint of salmon color and a dark green color of a Christmas tree were usually used, and the black color of the initial print and the white color of the background to some extent turned the two-tone prints into four-tone ones. Less common is yellow paint of a brown tint in combination with lilac. The third paint, which was first added to the red and green, was not quite in harmony with them, yellow, and then these colors were added to a tender grayish-blue. Japanese chromacelography soon began to use an infinitely large number of colors, as well as silver and gold; but her early works fascinate our eyes with their modest little color, and if in all of this “empty” art dedicated to actors and prostitutes with long-nosed faces and ugly body forms, you can find some charm only in terms of technology and color, you cannot deny that the best of these prints easily and gracefully convey the ideal side of the mores of the Japanese theater world and tea houses.

Wood engraving was not, however, the only branch of artistic technique that flourished among the Japanese. At the turn of the XVII and XVIII centuries, Korin Ogata, "the most Japanese of all Japanese painters," devoted himself mainly to lacquer painting. Its peculiar beauty is distinguished especially by its golden lacquer with tin, lead and silver inlays. Just as this artist in Kyoto, Ritsuo in Edo put the art of varnishing on national soil.

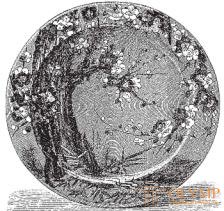

Pottery in Japan received a new development from the time the shogun Gideioshi brought several skilled potters from his victorious campaigns to Korea (in 1592 and 1597) and settled them in different provinces of his empire. Now, along with the glazed earthenware, which continue to be Japan’s pride, real porcelain appears, imitating Chinese. The Japanese, thanks in part to the Koreans, and partly independent studies, managed to unravel the secret of the production of Chinese porcelain, at least a hundred years earlier than the Europeans. The first experiments on the preparation of Japanese porcelain were made in the province of Gitzen as early as the 16th century, but only around the middle of the 17th century did the Japanese learn to paint on glassy glazes. At that time, huge porcelain factories, which initially worked only for the Japanese, but soon began to supply luxury goods to Europeans, also began to find sales for their products in the extreme west of the Old World. These products are named after the province of Gitzen and the factory point of Arita, or Imari harbor, through which they were exported. In Europe, they are especially rich in the Leiden and Dresden museums. Since Ernst Zimmermann researched and put in order the Dresden collection, we know that, contrary to what was believed recently, it is not only rich in luxurious vases painted in gold and red with gilding and made in three or five completely identical copies. to be sent abroad, in Japan itself almost not considered Japanese, but also rich in excellent examples of antique porcelain made for the Japanese themselves. In the first group, the main thing of which is a bowl 56 centimeters wide, the colors are blue, light bluish-green and partly iron red. The second group, in which flowers, landscapes and garlands, combined with linear patterns covering the background, shine bright and brilliant like a varnish, red and dark blue colors, include only bowls and bowls with lids. Among the blue porcelain of the third group, which until now was believed to be Chinese in Dresden, two bowls in the form of a blossoming flower are especially remarkable. "Cobalt blue paint," said Zimmermann, "although it never reaches such strength and density here as in the best works of Chinese art, but far surpasses Chinese in the grace of its application to business." The Japanese porcelain, which the Japanese themselves bought up and highly valued, primarily includes vessels from Kutani, Kaga province. Drawings for a delightful enamel painting on Kutani porcelain, executed on black contours and representing a magnificent combination of emerald green, straw yellow and violet colors, composed, apparently, by none other than Morikagge himself, the best student of Kano Tania. To get an idea of these drawings, it is enough to look at the spring landscape depicted on a dish from the Gonze collection in Paris (fig. 627).

Fig. 627. Japanese porcelain dish. The work of Morikagge. By gonze

Fig. 628. A clay vessel by Ninsei. By Bing

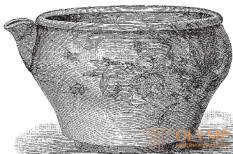

But the main workshops of colored glazed stone utensils originated in Kyoto and Satsum. Kyoto's glazed clay products delight connoisseurs with their deliberate roughness, impressionistic coloring, strong, rich and simple colors. They are always left a piece, not covered with glaze, in order to be able to see the quality of the clay. The glaze dripping and dripping from a thing is sometimes used as a grateful decorative means. Landscape motifs of ornamental painting are constantly styled according to the technique. The development of this branch of art in Kyoto is associated with the names of famous artists. Painter Ninsei, who lived in the middle of the XVII century, is considered a master in this field, who freed Japanese art from Chinese and Korean influences. He is credited with introducing an excellent combination of three colors, gold, blue and green, against the background of a cream color - a combination that informs many vessels that came out of the Kyoto workshops, so peculiar charm.

Fig. 629. The old Satsuma vase. By gonze

The rare ingenuity of Ninsei was shown both in the forms of his vessels and in small plastic works that came out of his hands. This artist owns the vessel depicted in Fig. 628, borrowed from one illustrated Japanese essay. But in the first half of the 18th century, the younger brother and student of Corin Ogata Kentsan (1661-1742), to whom Brinkmann devoted a special work, occupied a position in Kyoto as no less honorable than that held by Korin Ogata himself. He made dishes for use in tea societies and combined fast, but faithful, transmission of landscape nature with extraordinary technical style; his paints, of which the emerald green covers often whole surfaces, are distinguished by their strength and luxury, which cannot be found like. The Hamburg Art and Industry Museum has one of the most beautiful, but not one of the most extensive collections of Kyoto products.

Finally, Korean traditions have lasted the longest in Satsuma province. The real and unreal products of this province, which flooded Europe in the late XIX - early XX centuries, as in the XIX century, flooded its porcelain Gitzen, can not avert our taste from the really old Satsuma. According to Brinkmann, the finest of the "old Satsums" should be considered "those noble products in which for one hundred and fifty years the only decoration of small dishes, exclusively made from local clay, was a glaze of ivory or ivory color, evenly studded with small cracks and later served on real Nisiki de Satsuma products, an excellent background for delicate gold painting and other paints (the so-called brocade painting, painting brocade). The vase in Fig. 629 corresponds to this type of product; Bing's lecture in Paris.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)