The last time of the great flowering of Japanese art begins in the middle of the XVIII century and ends in the second third of the XIX. At this time, the high state of national Japanese art is expressed by its realism in the spirit of the people. Some researchers believed that only the art of the first half of this period fully deserves the name of the Japanese, the art of the second half, when Katsushika Hokusai appeared in it, which Europe first adored Europe, they recognize as already affected by knowledge of the European perspective and European sense of nature; however, we can only partly agree with this opinion. We generally do not take into account intentional imitations of European art. Introduction to the use of European aniline paints seems to us an unforgivable step backwards. Although the Japanese gradually began to discover that there is a more correct perspective and more accurate anatomy than those that were known to the Chinese, we cannot, however, blame their artists for the fact that in practice they use these discoveries to a very moderate degree and along with this did not stop looking at their East Asian nature with East Asian eyes. In fact, these discoveries began in the first half of the period under review. Syunso, Harunobu, and Kiyonaga, in their own stylish way, however, made little concessions in favor of the new perspective and new forms than Hokusai and his associates made later, subordinating their sense of style to the feeling of nature.

Fig. 630. Poetess Komati. Netsuke Miva the Elder. By gonze

Applied art, in which the names of artists are now more and more common, still prevails among the Japanese. Netsuke depicted in our drawings already belong to this time, namely “Poetess Komati” by Miva the Elder, located in the Dreyfus collection in Paris (Fig. 630), belongs to the middle, and “Snail” is from Tadatoš’s Bing collection (see Fig. 608 ) by the end of the XVIII century. But the Japanese applied art of this time was also led by realistic painting, the best representatives of which delivered to him countless samples. Painting was the dominant branch of art and in this period, and with her in even closer connection was hromoksilografiya. The most famous painters of that time were at the same time famous masters of colored engravings.

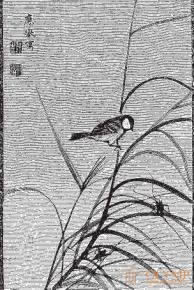

Fig. 631. Okio. Tit and beetle. By gonze

The Shiyo school, which flourished in Kyoto and got its name from one of the streets of this city, as well as the Uiyiyo-e folk school itself, which is also called the Vulgar school of art and crafts and whose residence was the city of Edo, both sought similar goals. , held almost parallel direction. But at the same time, the school of Shiyo was predominantly still along the ruts laid by the Chinese, while the Ukiyo-e school laid its own ways for itself.

The main masters of the Shiyo school are: Okio (1733-1795), Goshun (Gokkei, also called Yentsanom, 1741-1811), Pines from Osaka (1747-1821) and Yosai (1787-1871). Only the fifth master, Hanku (1749-1838) can be counted among them only indirectly.

Fig. 632. Pines. A monkey. By gonze

The development of the Ukiyo-e school we traced almost to the middle of the XVIII century. At that time, she set herself the main task of portraying the actors and fashionable beauties of the capital of the shoguns, and used chromoxylography for reproduction and distribution of her works.

In the middle of the 18th century, Khasikawa Toyonobu (died in 1789), a student of Shigenaga who replaced the third, yellow, blue paint, and Torii Kiyomitsu (died about 1765), who depicted in addition to everyday life, came to the fore in part of the tricolor painting. actors of the bathing scene and other scenes from everyday life in the style of Ukiyo-e. When Kiyomitsu's activity came to an end, Harunobu appeared as a bold innovator.

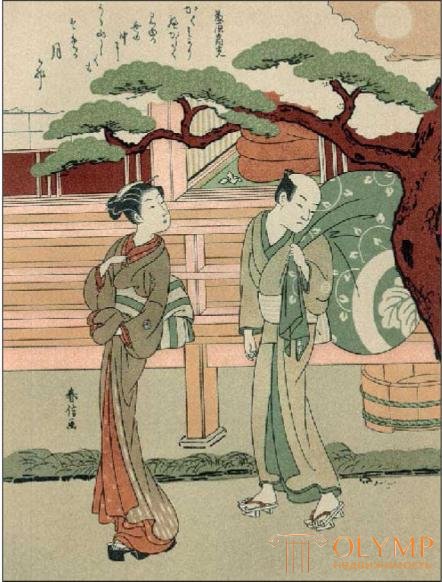

After Harunobu, in the first half of the period under review, which almost coincides with the second half of the 18th century, Shigemasa is a representative of the highest state of the Ukyyö-e school. 1750-1814) - a representative of the “majestic and simple and beautiful” and Syunso (died in 1792) - a particularly skilled figure-maker of actors. Torii Kiyonagu recognizes as the greatest master of chromalography in the history of Japanese art. His sheets, representing actors and women, are even clearer in contours and clearer in colorful tones than Harunobu prints. In some of his works a gentle chord is made up of mauve paints, salmon red colors, yellow and mat green. He is a true classic in this branch of art.

Rival Kiyonagi Katsukawa Shunso - the ancestor of the branch of his name, separated from the school Uiyiyo-e. He is considered the most ardent portrayer of artists of the theatrical scene and artists in love. The most famous of his series of actors and beauties were published in 1770 and 1776. In 1774, he published, in addition, a collection of one hundred portraits of poets. He could impart passion and seduction to his moving figures, their faces with high eyebrows, long noses and slanting eyes, faces that are insignificant and look like masks by themselves are an attractive, somewhat sensual expression, and their rich, fluffy robes fascinating harmony paints. In the 19th century, Parisian art connoisseurs were delighted with his works.

Kiyonaga is adjacent in style to the famous Utamaro Kitagawa (1754-1797), which in 1886 Edm. de Goncourt devoted a special monograph. But compared with Kiyonaga Utamaro, there is more a mannerist than a classic. His figures and faces are stretched out, women began to differ in painful-sluggish movements, in his engravings a fantastic symbolism spread, characterizing him as an artist of the era of decline.

The last five of these masters are also known as painters. All of them were represented by their paintings at the New York exhibition in 1896. For example, it was owned by Fenollosa Kakemono Shigemasy, depicting a busy road passing by rice fields. Phenollosa said that there is no other landscape of the Ukiiyo-e school, which, to such an extent as this one, would arouse in the connoisseur of Japan longing for this country of gods. From the works of Korusai, a large board of a wall screen with the image of an old woman, a former dancer, was put up with a lantern and a knot in her hands. Phenollosis considered this picture one of the best works of the artist. Kiyonaga was represented by a picture from the Vanderbildt collection, written in 1781 and representing three girls on the river bank, and a picture from the Phenollosa collection, 1789, depicting a girl in a light red dress under a willow. Phenollosis regarding the first of these paintings said that the transmission of air in it defies any description, and in the second it noted the unprecedented originality of red paint. Of the works of Syunso, a Kakmono Phenollose belonging to the lady behind the toilet was exposed, and her reflection is amazingly well drawn in the mirror. Finally, there was a picture of Utamaro Kitagawa from the Vanderbildt collection, with two girls returning from bathing; Phenollosa called this picture "the triumph of painting" and, moreover, "extremely original."

Fig. 633. Japanese woodblock Harunobu. From the original

A little later, Syunso appeared on the stage of Toyogaru Utagawa, the head of a branch of the same school known by his name. Toyogaru Utagawa, who died at the beginning of the 19th century, wrote mostly multi-figured scenes in confined spaces, especially in theaters and tea houses, and, despite the abundance of persons acting in them, could arrange them without confusion, was distinguished by the diversity and warmth of colorful tones and in his the compositions made the strings of the inner life sound. At the New York exhibition he owned four paintings.

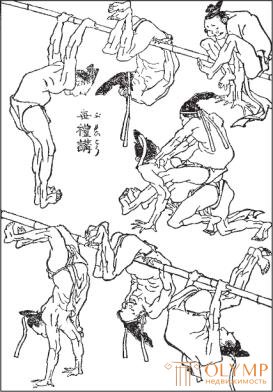

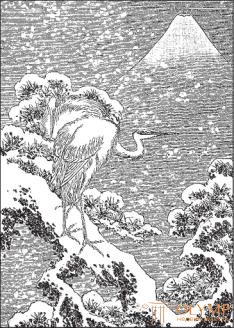

Favorite student of Syunso Hokusai (1760-849), who was known for his loud popularity in Europe and the most valued of all Japanese artists, was born in Edo and throughout his life spent in incessant work, produced an incredible number of paintings, drawings and, mainly, engravings on the tree. His paintings are relatively rare. However, the British Museum owns a large silk kakmono of his work, with a picture of the plot from the Japanese heroic saga, a bold, majestic and somewhat fanciful picture in the picture and heavy in color. The Girk collection in Berlin contains, besides a series of lightly sketched sketches by Katsushik Hokusai, two of his small sheets depicting genre scenes; His works are also found in English and French private collections. But especially many of his paintings are in large American collections. At the New York exhibition in 1896 there were more than a dozen. On one group of women depicted in full-size on a wall screen (owned by Ketchem), Phenollosa said: "There is not a single European master, starting with Dürer and Titian, then with Velázquez and ending with Sargent and Whistler, who would not have welcomed this piece as one of the most prominent in the world. "

The originality and versatility of Hokusai are quite evident in his woodcuts, the study of which, begun in 1882.

Fig. 634. Hokusai. Japanese acrobats. Engraving. By Bing

Fig. 635. Hokusai. Crane and Mount Fuji. Engraving. By Brinkmann

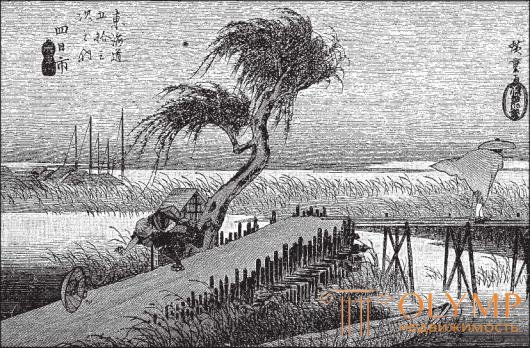

Along with this follower of Katsukawa Shunso, we must follow the successors of the school Toyogara Utagawa. Her pupil Toyokuni Utagawa (1772-1828), whom Gonze called great, and Phenollosa glorified as early as 1884, was one of the favorite Hroxylographographers of the Uchiyo-e school. Ему приписывают введение пурпурной краски в гамму колеров гравюры. Брат этого художника, Тоёгаро Утагава (ум. в 1828 г.), прославился кроме своих книжных иллюстраций цветными гравюрными пейзажами, отличающимися более правильной перспективой, нежели та, которая до тех пор была известна японцам, и вместе с тем чисто японским импрессионизмом. Так, например, в одном приморском виде этого художника линия горизонта моря совсем отсутствует, но пара далеких парусов, изображенная на высоте этой линии, дает чувствовать ее вполне. Тоёгаро, кроме того, играет в истории развития японского пейзажа видную роль как учитель Хиросигэ Андо (1797-1858), художника, ушедшего вперед дальше всех японских пейзажистов. Славу Хиросигэ доставили главным образом отдельные листы гравюрных пейзажей, которые он издавал. У него появляются европейские перспектива, передача теней, зеркальность воды; но эти все еще далеко не вполне усвоенные им технические приемы нисколько не нарушают его основного, сильно декоративного, японского приема передавать природу (рис. 637). Изображая, например, громадные синие волны, набрасывающиеся на берег, их пену он рисует согласно старинной орнаментальной схеме волн; темно-синий цвет его дневного неба или ярко-красный вечер него – умышленные усиления красок природы для пущей внятности декоративного эффекта. В XIX столетии японское искусство не могло принять никакого другого направления, кроме этого.

Fig. 636. Gokkei. Fisherman with an umbrella. Picture. By "Gazette des beaux-arts"

Considering the history of Japanese art, we have reached the final point of its development and at the same time the development of East Asian art in general. For Japan, which, after it at the end of the XIX century. She mastered the European science and technology, managed to defeat the gigantic Chinese Empire jokingly, of course, it became impossible to ever again bow down to Chinese artistic views. The question is whether her own artistic powers are sufficient to, on the one hand, invariably hold on to her national ornamentation, to which all European wisdom cannot add anything, but on the other, to give its free art its new roots. on the natural historical ground of European artistic knowledge (anatomy, perspective, etc.) and at the same time remain faithful to its East Asian and national Japanese feeling.

Fig. 637. Hiroshige Ando. Storm. Chromoxylography. From the original print

The great Indo-East Asian art in its totality is the opposite of the great West Asian-European art in its totality, which, being ancient than it, at all times, pagan, Christian and Mohammedan, had a versatile influence on it still not sufficiently discernible in all works, but nowhere, neither in India and Tibet, nor in China and Japan, has completely eradicated the main national features of this art. Pre-Buddhist Indian art, of which only poetic memories are preserved, and pre-Buddhist Chinese art, known to us - with the exception of the ancient bronze vessels - almost only from the drawings of Chinese historiographers, apparently, differed from one another as much as they differ from friend Aryan and Mongolian mindset. Since India, moving soon after the introduction of Buddhism in it to architecture and stone sculpture, made a decisive step forward in the field of monumental art, this finally alienated it, in terms of arts, from China, in which calligraphy and applied art. But then the Buddhist figurative art of India, the main force of which was the development of types of gods and saints not without influence from the Greco-Roman art and grouping them into narrative images, spread through the wide stream from northern India to Tibet and China, reached Korea and Japan, everywhere fertilizing other fields, but never flooding them or losing them. The Buddhist-Brahmanian monumental art of India spread through Southeast Asia to the remotest islands of the archipelago and, absorbing new forces from this new soil, gave rise in Indochina, as well as on the island of Java, such marvelous works of art as enormous and fantastically majestic which can hardly be found in his homeland. Meanwhile, Chinese national art, insignificant and petty, grew into a slender tree, the most lush flowers of which were not deprived of noble forms or tender fragrance, and this flowering tree of Chinese art spread its branches throughout Korea and Japan, where they are especially in Japan - brought ripe, excellent fruits until new, local shoots began to grow in the shade of these branches, covering the soil with fresh, lush greens, but adopted by their own efforts to aspire to the sky not earlier than the end but the branches of a decrepit Chinese tree that overshadowed them rotted.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)