In Japan, as in China, Buddhism, degenerated into a cult of idols and transferred from Korea across the sea in about VI. in our chronology, preceded by an ancient national religion, without costly sacred images. But the history of the pre-Buddhist art of Japan is out of the question. The ancient religion of Shinto, gradually transformed from the original worship of nature to the cult of ancestors, began to create idols not before being amalgamated with Buddhist and Taoist views, and, in order to survive, had to enter into a peaceful contest with the teachings of the great founder of the Ganga coast religion; original samples of its extremely simple temples, hardly distinguishable from the huts of ains, could not reach us already because religion prescribed from time to time to destroy these small Shinto shrines and build new ones instead.

Thus, the most famous of the shrines of Shinto (Miya) in Japan, the temple in Issa, first built in the first century. n e., despite all its later restructuring, has retained its ancient basic shape and former dimensions. This simple little building of logs driven to the ground with a rectilinear roof, a strong protrusion that brightens the front around the sanctuary, with the ends of gable rafters highly prominent above the roof in the form of horns, gives some insight into original Japanese art, which was at the highest level of art primitive peoples, which only we know.

The history of the development of art in Japan has a more obvious connection with the internal coups in its political history than with the phases of the history of its religion. Until the 18th century, Japanese art was aristocratic. The clans of Japanese artists themselves, whose activities, enclosed in a particular artistic direction, can sometimes be traced back over many centuries, were all noblemen, in which art was mostly passed down from generation to generation. The flourishing periods of Japanese art coincide with the prosperity of famous dynasties, whose eminent members not only forced the art to serve themselves, but also practiced it quite often themselves.

Yamato Province was the main arena of the history of Japan’s state, spiritual, and artistic development. Nara, the ancient capital of this province, was the seat of the Mikado (emperor, tenno) until Emperor Quanmun (782-806) transferred his residence to Kyoto. The ninth century, in which Nara and Kyoto flourished simultaneously, was the first flourishing period of Japanese art.

X century in Japan can be called the time of chivalry. Noble families of noblemen (daimyo) Tahir and Minamoto, whose predecessors were Fusiwara, led because of the predominance of bloody feuds among themselves and with the emperor. These quarrels led to the fact that one of the Minamoto clan, Yoritomo, received from the emperor the title of commander-in-chief (shogun) with the rights of supreme secular power and in 1184 founded in Kamakura, on the shore of a sea bay, at the foot of the sacred Mount Fuji, the second capital, equal to Kyoto's imperial residence. From this time until 1868, the shoguns (Taikuns) were valid, and the Mikado were only fictitious masters of Japan. The twelfth century, in which this dualism arose, was the second flourishing period of Japanese art.

The era of the most enlightened and not indifferent to the art of the shoguns, descended from the surname Ashikaga, falls on the XV and XVI centuries. The shogun Yoshimas of the named family, who died in 1489, was himself known as a painter. His time is the third blooming period of Japanese art.

After the Ashikaga clan, the Tokugawa clan rose. The shogun (died in 1616) transferred the residence of the shoguns from Kamakura to Jedo from this whole family. Gonze decisively asserted that the first century of the shogunate of the Tokugawa family, corresponding to our XVII century, was the fourth flourishing period of Japanese art, while Phenollosa disputed this. In fact, in this century, together with the lush late flowering of the former Japanese art, some beginnings of the new appeared.

But that the last times the Tokugawa surnames, especially the time span from 1750 to 1850, were indeed the epoch of the fifth, and last, flowering of Japanese art, although it was sometimes denied, but in the end it was always recognized again.

Thus, the history of Japanese art begins, in fact, only with the introduction of Buddhism in the VI. n e. In the creative "twilight", in which was then the Land of the Rising Sun, brought the light of the art of the Heavenly Empire, believed to have emigrated to Japan or Korean prisoners of war. Then we see that Japanese artists of all specialties travel to China to study classical East Asian art at its very source, or that Chinese artists migrate to Japan to reap laurels and make capitals as teachers of their youthful young brothers in race.

Fig. 612. The guardian of the temple. Tree. According to Anderson

The most ancient Buddhist temples of Japan belong to the magnificent shrines that adorned the ancient capital of Nara in the 7th and 8th centuries. The first Buddha temple in this city was erected under Emperor Shiumun (724-749), and the beautiful temple of the goddess Kuanon (Kuan-yin from the Chinese), ibid, under Emperor Quamun.

The magnificent architecture of this time was decorated with large sculptures. The colossal bronze gilded figure of the seated Buddha (Daibutsu), for which the temple of this god was built in Nara, was cast in 739. This statue, with the exception of the head, renewed a thousand years later, is wonderfully executed and distinguished by its clean forms and especially impressive grandeur. If the depicted god had risen to his feet, he would have been 42 meters tall. However, such statues of the Buddha - classical, but not in Chinese, but in the Indian spirit, and in which we are struck in Japan, as in China, the absence of features of the Mongolian type, did not have any further historical development. Therefore, it is more interesting for us to have wooden figures produced along with them, freer for work, more closely imitating nature, although also generated by the needs of Buddhist worship. Two remarkable temple guards of this kind, opened in the 80s. XIX century. in another temple in Nara, they are considered perhaps the most ancient of the remaining works of Japanese sculpture, namely sculptured in the VII century. But these works are attributed to Korean masters, and they show anatomical correctness, which even later Japanese art could hardly achieve, the ability to mobility is seen, completely contrary to the principle of the frontness of the sacred statues of that time, so much of this movement is visible that, with all the vitality of these figures, there is something restless, unrestrained in them (fig. 612). Such statues were painted and placed in the niches outside the Buddhist temples; they personified, probably, two great Brahmin gods, Brahma and Indra, relegated to the degree of service spirits of Buddhism.

In the second half of the ninth century. worked painter first blooming pores of Japanese art Kose-no-Kanaoka. Gong compared it with Cimabue, Phenollosa - with the greatest artists in the world - Fidiy and Michelangelo. However, what is attributed to him from among the "kakmono" who gained fame in Europe, what, for example, the image of the Buddhist deity Dziyo published by Gonze, belonging to one private person in Japan, reminds, at most, Cimabue (Fig. 613). These paintings of Kose-no-Kanaoki are believed to have survived only in the temples of Nara and Kyoto. U-tao-tzu, the paramount Chinese artist of the times of the Tang dynasty (see Fig. 591, a), served as a model for him, from whose works the main image of Nirvana Buddha has survived to this day in one of the Kyoto temples. The main motives of such images of Nirvana were already pre-announced in the reliefs of the Gandhara school, and that the Greek-Roman remnants of the language of the forms of this school were inherited by Japanese Buddhist painting from the same painting in China, can be seen from much later Japanese paintings of this kind, as Grunwedel pointed out. Buddhist religious painting proper, in both Japan and China, has up to now a special direction that exists alongside others and is distinguished by the greatest possible smoothing of Mongolian-type features, rich colors, love of gilding and a smooth overlay of color schemes inside the contours. Under the successors of Kanaoki, who were at the same time his descendants from the name Kose, this purely Buddhist trend remained dominant for a hundred years.

Fig. 613. Buddhist deity. The picture attributed to Kanaoka. By gonze

At the end of the XI century. There was some reaction against this trend in the person of one of the students, Kose Motomitsu, of Fusiwar’s last name. Motomitsu, the work of which is considered one original Buddha image in the collection of Girke in Berlin, was the founder of the Yamato school, which later turned into the Tosa school. The Yamato-Tosa school is viewed as the causative agent and keeper of the national trend, the opposite of Buddhist, Chinese and later popular-realistic aspirations in Japanese art. However, in this school, nationality obviously showed itself more in the choice of plots, which she liked to take from legends, from the history of chivalry, from life and nature of Japan, than in the way of image and technique, in which she continued to keep the previous techniques of working with a thin brush and variegated paints.

Fig. 614. Fighting rider. Painting school Tosa. By Bing

The Yamato School flourished in the twelfth century. Its main masters, what are the "divine" Takanobu, Mitsunaga and Keion, "the greatest draftsmen of Japan", and Tamegissa, "the magnificent, whose paints compete with Titian", Phenollosa was ranked among the greatest painters of all time, but apparently put them too high. In the thirteenth century Tsunetaka, also from the family Fusivara, adopted the name of the province of Tosa for himself and for his school, and from that time the school of Tosa continued to flourish under this name, which the Japanese old temper associated with the concept of the most aristocratic and most national art direction in their country ( Fig. 614). According to Anderson, the paintings of Tosa school in Japan, which more often have the appearance of a side screen than a kakmono, produce the same impression as their miniatures of European medieval service workers with their bright, lively colors on a gold background, only often in an enlarged size.

Fig. 615. Woodcut. According to Anderson

It is believed that this school introduced a technique in Japanese painting to depict roofless houses when you need to take a look at what is happening inside. Fig. 615 represents this technique applied in the woodcut of Sukenobu (1742). Then, in the XII century. the son of the name of Minamoto Toba Sojo laid in this school the foundation of a new kind of painting, humorous and caricatured, and satirical painting, established since then in Japanese art, became known as Toba-i (Toba's style).

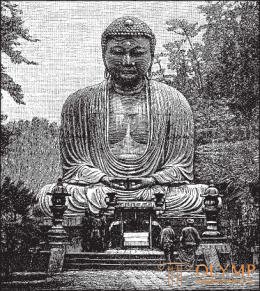

Whereas in the flourishing era of the XII century, painters continued to work mainly in Kyoto and Nara (Kasuga), in Kamakura, in front of Ioritomo, architects, sculptors and gunsmiths showed vigorous activity. In the main temple of Kamakur, a colossal statue of a seated Buddha was placed (fig. 616), almost the same in size, form, and technical design with the same statue in Nara; this statue is better preserved than the statue in Nara, which later was attached a new head; but the temple, where it stood, fell apart, and now the impression made by this statue among the verdant luxurious nature must have been extremely grandiose. Minted iron plates and coats of arms of the knightly age under consideration, the masters of which considered themselves sacred and blessed by heaven by artists, are still preserved here and there in the treasures of Japanese temples.

Fig. 616. Sitting Buddha. Bronze statue in Kamakura. From the photo

In the 13th century, Japanese ceramics were improved to some extent. Our acquaintance with its history is primarily due to the writings of S. Bing and the Japanese Oued Tokunosik, written in French. The potter's wheel was brought to Nara and Kyoto by the Korean priest of Giogi in the VIII century. The first glazed stone dishes, one-color, like celadon, were made in the following centuries according to Chinese designs. Since the XIII century. tea houses spread in Japan. The need of the Japanese for pottery prompted the famous potter Koshiro to make a trip to China in 1223-1227, in order to study its production. Returning from there to his homeland, he founded in Seto (in the province of Ovari) large pottery houses, from which colored glazed stone (but not porcelain) dishes received everywhere in Japan the name of the seto (netomono) products. The charm of old seto (co-seto) products lies in their beautiful forms and the brilliance of their brown glaze with multi-colored spots.

During the 14th century, the quality of Japanese art declined under the influence of the Tosa school, which became more and more conditional.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)