The painting of the first centuries of Christianity keeps us in the catacombs; of all the plastic arts, it was she who, in the ceiling and wall paintings of the burial chambers, achieved the greatest brilliance, and it was in catacomb painting that for the first time Christian art spread its wings for independent flight.

We owe our acquaintance with catacomb painting primarily to the studies of J. B. de Rossi, L. Perret, T. Roller, Ios. Vilperta, F.-Ks. Kraus, Victor Schulze, Yog. Fichera, O. Marukki, Ios. Fuhrer and their predecessors. Then, along with special works regarding this painting by researchers such as Ezh. Münz, L. Lefort, O. Paul, Hell. Gazenklever, A. de Val, Edg. Genneke and Wilpert (his major essay is Catacomb Paintings of Rome), monographs should be written on almost every single subject of ancient Christian art, and the authors' differences on one issue or another are partly due to their belonging to different religions.

From an artistic point of view, the Roman catacomb paintings, best studied, belong to the type of hand-crafted Roman-Hellenistic grave frescoes. As in the pagan wall painting of the Etruro and Roman hypogues, they, with a few exceptions, are dominated by a white background, due, however, to the weak illumination of the catacombs. This background is always made alfresco, that is, it is induced on a still wet layer of lime plaster, the images themselves are written in part also alfresco, partly on dried plaster. Although in places there are whole small landscapes of an idyllic character and often elements of the landscape are part of one or another scene, this last one does not have a solid background at all. But the catacomb images of this era have not yet returned to the black contours; the figures are delineated quite softly and naturally, and the more ancient images compare favorably with the later ones with a more correct pattern and a greater freshness of tones.

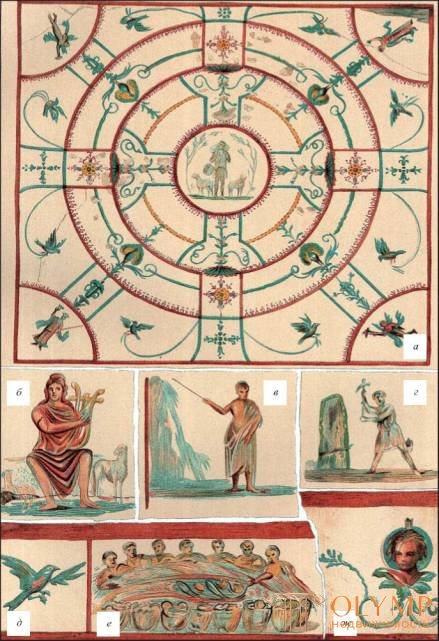

At the heart of the pictorial ornamentation of square ceilings of cubicles (as well as pagan ceiling painting of the same time) is usually the division of the ceiling into fields proceeding from a circular central field, this division inscribes the outer circle or octagon into an equilateral quadrilateral and then diagonally divides the entire area into segments of various shapes (Fig. 3, a). Borders of fields are often marked only with red or blue stripes, but often these are also seated with hooks, crosses, triangles, teeth, bows, or turned into Ionic pearl cords. The favorite Greek motifs of the linear ornament, a number of waves and meander incident on one another are rarely found, but the more often instead of simple lines or between them are the antennae of plants, leafy branches, vine shoots, flowers on stalks, garlands and flower vases; Acanthus leaves are usually depicted at the base of deciduous petioles and flower shoots.

Fig. 3. Painting in the catacombs of St. Kalliksta in Rome: a is the ceiling in the second chapel of the Holy Mysteries; b - Orpheus, on the ceiling, “Cubicolo dell 'Orfeo”; c - Moses; d - grave digger (Fossor); d - pigeon; e - the meal of seven; g - a mask from the second chapel of the Holy Sacraments. By de Rossi

Those of the pagan animals and human images, which have long lost their mythological significance and turned into purely decorative elements, were borrowed from the Christian ornamentation ingenuously, without trying any symbolic interpretation. Panthers, goats, seahorses, birds, masks (f) alternate with geniuses and psychos in long robes, wingless cupids and winged babies-geniuses who, no matter how remind us of later Christian angels, should not be taken for them. In other cases, ancient symbols are interpreted in the Christian sense, as the Dionysian vine can serve as a particularly clear example. Let us recall the words of Christ to his disciples: "I am the vine, and you are grapes." The dove in ancient Christian painting was a symbol of the world, the Christian descended on the soul (e). The peacock, whose images with a flowing tail we find in many frescoes, was attributed to imperishability, so that it symbolized immortality. Anchoring as a symbol of Christian hope is already indicated in the Epistle of Paul to the Jews. As for the symbolic meaning of the fish and the lamb, they lead us already to the pictures in which they are depicted together with the figures of the fisherman and the Good Shepherd. The fishing fisherman is a symbol of the apostle rybayaris, who are told that they will become "fishers of men." The interpretation of water, the vital element of fish as the water of baptism, soon joined here. Thus, the fish at the beginning is the symbol of the person who has been baptized; only a little later does it become a symbol of the Savior himself, and then in this meaning is reproduced countless times. The establishment of this new symbol happened, as the Fathers of the Church testify, because the initial letters of the Greek words Ιησουζ Χριςτοζ θεου Υιοζ Σωτηρ (Jesus Christ the Son of God the Savior) make up the word ΙΧΘΥΣ, that is, "fish." Similarly, the lamb's symbol occurred. "I am the good shepherd," said Christ, "and when someone finds his lost sheep, he will take it with joy to his ramen." Already in the earliest catacomb frescoes, the Savior is depicted as the Good Shepherd carrying a lost sheep on his shoulders (a, a central figure); Accordingly, the lamb at first designated a person saved by the grace of Baptism, and only in post-Constantine time became the symbol of Christ himself, on the basis of the words of John the Baptist: "Behold the Lamb of God, take the sins of the world." In such a case, he is surrounded by apostles, also depicted as sheep. Attempts to attribute in all cases the same meaning to figures of worshipers with raised hands, usually female (orans), were not crowned with success. These figures in catacomb painting are elements of historical compositions, then earth (according to Victor Schulz) or celestial (according to Jos. Wilpert) portraits of the dead, and only in the post-Constantine epoch personify the Most Holy Virgin or Church. In other cases, finally, they are placed at the corners of the plafonds along with geniuses and victories as purely ornamental motifs.

Many of the catacomb frescoes testify to the ability of Christian painters to transmit separate religious ideas in simple but understandable and touching images and to reproduce biblical and evangelical events.

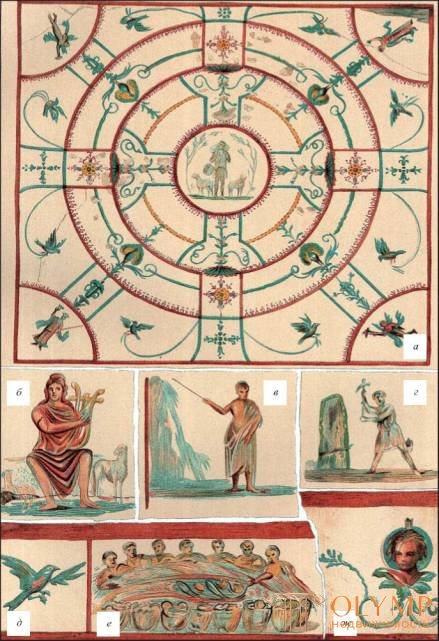

In one ancient Kirensk catacomb we meet the Good Shepherd with a lost sheep on his shoulders; around him are seven lambs, and above him are seven fish. Here lambs and fish symbolize the Christian community. On the contrary, in the ancient frescoes of the catacomb of Vigna Cassia in Syracuse, the images of the Good Shepherd are connected with biblical scenes; of these, the story of Jonah deserves special attention, the prophetic meaning of which is witnessed by Christ Himself, who saw in it the type of His death and Resurrection. Particularly interesting are the wall and ceiling murals of the catacombs of St. Januaria in Naples. On the ceiling of the front chamber of the upper tier among the pagan ornamentation, we suddenly encounter biblical scenes. It is curious that the image of Adam and Eve under the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil differs only slightly from the modern images of this plot. But the vast majority of Christian frescoes that have come down to us from the first centuries are decorated with underground cemeteries of Rome. How individual images were placed on walls and ceilings can be clearly seen in the example of one of the so-called chapels of the Holy Sacraments in Callistus's cemetrium (Fig. 4). The middle field of a lightly and gracefully dissected ceiling represents an image of the Good Shepherd with a sheep on its shoulders. On the left, right at the entrance, the young man Moses is depicted (see Fig. 3, c), exuding water from a rock with a baton (the rock is yellow, the water beating from it is blue); on the right, in pandan to this figure, is a female figure scooping from the well, over the edge of which the water of eternal life flows. On the left (from the entrance) wall, above, we see Jonah being thrown into the sea by sailors, and the “big fish” - a monster with a long neck and a huge tail rolled into rings that swims up to swallow the prophet; in the middle lower field, on the left, a fisherman pulls a fish out of the water, and on the right a man in an apron baptizes a naked boy in this water; but here we have an indication, rather, of baptism in general, than of the baptism of the Savior. To the right of this last composition, the healed, relaxed, is removed, putting his bed on his shoulders; Pandan image on the left side - repulsed. On the right wall from the entrance, only the image (corresponding to the composition on the opposite wall) of Jonah, erupted by a monster (see Fig. 2, b), was preserved. On the wall opposite the entrance, in the same place, is presented the already saved Jonah resting on the shore; below, in the middle field, the composition, which, according to de Rossi, can be interpreted as a meal of seven disciples of the Savior, who were honored by His appearance after the Resurrection at the Sea of Tiberias. To the right and to the left are two scenes with the same motif of hands raised to the sky; to the right - stand in the pose of Abraham and Isaac, thanks to God after the miraculous appearance of a ram; to the left - male and female figures stand next to a tripod, on which fish and bread lie; the man touches the fish, and the woman holds her hands up. It is difficult to decide whether we should see the Eucharist here or just a home pre-dinner prayer. To the right and to the left of these images is placed, in a special frame, on the beardless male figure with a pickaxe in raised hands: these are the grave diggers (fossors) who worked on digging the catacombs (see Fig. 3, d).

Fig. 4. One of the chapels of Cemetheus Callixtus in Rome. By de Rossi

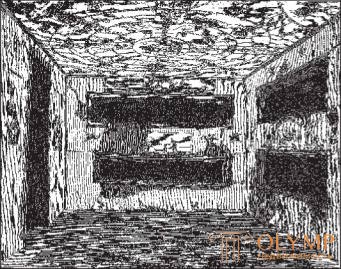

Fig. 5. Psyche. Fresco crypt of sv. Nerey in the catacomb of Domitilla in Rome. From the photo

In artistic terms, first of all, the decorative unity of this painting, achieved by strictly symmetrical matching of its elements to each other, draws attention to itself. The mistake of some researchers, such as Springer, was to recognize this symmetry only in the ceiling painting of individual cameras. As for the content of these frescoes, it should be noted that here, as in other catacombs, purely decorative, symbolic, household and historical images are linked into one whole, reflecting the faith of Christians in the Atonement.

All images of this kind we find in the remaining Roman catacombs. The decorative cycle includes, for example, antique murals of the crypt of St. Yanuariya in the catacomb Pretext, with images of the seasons, personified figures of children collecting roses, ears, grapes and olives, or the fresco of the crypt of St.. Nereus is in the catacomb of Domitilla, where Psyche in long clothes vomits flowers (Fig. 5). On the contrary, in the circle of Christian ideas, the image of the legendary pagan singer Orpheus takes on a completely symbolic character. In the catacomb of Domitilla, on one acre, he is represented sitting among wild animals and taming them with the lyre, and on the ceiling of one of the chambers of the Callacst's catacomb, he is surrounded by lambs and, thus, approaches the type of the Good Shepherd (see. Fig. 3, b). Orpheus owes his appearance in ancient Christian art partly to the miraculous power of his lyre, partly to the idea of immortality, which Orphic sacraments were imbued with. However, already in the III century it disappears from the plots of catacomb painting.

Realistic images, in addition to so frequent fossors (see Fig. 3, d), are primarily portraits of the dead. But in these images the phenomena of reality are easily combined with symbolism. On the large mural of the “crypt of the five saints” in the catacomb of Callixte five male and female figures, whose names are marked with inscriptions, are depicted standing with prayer-upraised hands among the blooming paradise garden; similarly, “family meals”, which in their content can often be compared with pagan memorial dinners (cf. the frescoes of the Villa Pamphili, see v. 1), in some cases, such as, for example, in the so-called Greek chapel of the Priscilla catacomb, presenting fraternal meals (agaps), hint at the Last Supper or even the mystical heavenly feasts of the righteous.

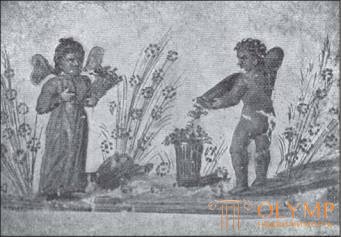

Fig. 6. The Mother of God, etc. Isaiah. Fresco in Priscilla's catacomb in Rome. By Roller

The following are the main images of the Christian cycle. God’s Father Himself in this epoch is not depicted yet, but His hand is often depicted coming from the clouds, as, for example, in the scene of Isaac's sacrifice in Ostrian cemetria or in the composition “Moses receiving the commandments” in the catacomb of St. Peter and Marcellinus. As for the image of the Savior, it appears already in the early catacomb painting, sometimes in the form of the Infant on the lap of the Mother of God, as, for example, in the beautiful fresco of the Priscilla catacomb (Fig. 6), sometimes in the form of a young man, as in the Baptism scene in the crypt of Lucina, sometimes still in youthful and beardless type, in the form of a miracle worker, for example, in the scene of the Resurrection of Lazarus in the last of the chapels of the Holy Mysteries; finally, by the end of this epoch, Christ appears as the Master among His disciples, for example, in the fresco of Ostrian cemetria. The earliest extant images of the Blessed Virgin are the above-mentioned murals in the Priscilla catacomb: Our Lady with Roman traits sits half-way to the left; Baby takes her breast. A star is depicted above it, and in front of it stands, pointing to a star, a beardless man, whom we, along with Kraus and Wilpert, recognize as prophet Isaiah (see Prince Isaiah Ave., VII, IX, Matt. I, 23) . This is a serious, calm, heart-telling scene in which, so to speak, all the future Madonnas are apprehended. Almost at the same time, the Most Holy Virgin appeared on the ceiling fresco of the same catacomb, but without the Child, sitting on a throne, in front of which stands a young angel-evangelist, perhaps the most ancient of the angels of Christian art that have come down to us. Throughout the pre-Constantine era, angels are depicted, as in the above example, in the form of wingless youths dressed in a tunic and cloak. In the form of winged youths they appear, adjoining the Hellenistic images of victories, first in the art of the Christian East, but also here only after the victory of Christianity over paganism.

Most of the Roman catacomb frescoes depict biblical events, and the Old Testament scenes are reproduced more often than the New Testament, with the exception of the Good Shepherd, and perhaps not just a coincidence that the oldest surviving Roman catacomb paintings, namely the Flavius gallery frescoes in the catacomb of Domitillus (Imititella) besides small decorative landscapes, a vine with winged children's figures and symbolic images of the Good Shepherd and a memorial meal, they contain only two Old Testament scenes: “But th in the ark "and" Daniel in the den of a lion. " Daniel is usually depicted naked, en face, between two lions in a heraldic style. Three youths in the fiery furnace have Phrygian caps on their heads and stand in the pose of orants among the flames. Noah, to whom the dove carries the olive branch, swims on the waves alone, in a small box (cf. with antique vase images of Danae, thrown into the sea).

The cycle of New Testament scenes in catacomb painting begins, as has now been established, with the "Annunciation." This is followed by the “Adoration of the Magi”, which are depicted in the number of two, then three, then four, in Phrygian clothing, marching to Our Lady holding the Baby in her bosom. Some of the murals of this era undoubtedly represent the baptism of the Lord. The latest category of New Testament compositions is the Miracles of the Savior. As for His Passion, their images are completely absent, unless they recognize, together with Wilpert, one of the scenes of the so-called crypt of the Passion of the Lord for "Warriors mocking Christ" or for "Scourging." In the scenes of Miracles, with the exception of Healing the Bleeding, the Savior is always without the apostles. Healed, it occurs at least 12 times. Almost twice as often, “the multiplication of breads by the Savior” comes across, which concerns the staff of the bread baskets before Him. The “Resurrection of Lazarus”, which looks like a mummy, standing in front of the entrance to the tomb, is repeated at least 39 times (Genneke). Do not forget that the victory over death was the core of Christian dogma.

In all the catacomb frescoes, the depicted action is played out with the least possible number of figures, extremely simply and calmly. Since the same subjects were interpreted approximately equally in all, including in the Roman Catholic Christian catacombs, it must be assumed that some painters-decorators of the cubicles did not assemble the images themselves, but adhered to the samples developed by collective creativity. Be that as it may, this alien external effects painting came out of the heart and speaks primarily to the heart.

К древнехристианской живописи можно отнести также изображения на золоченых стеклянных сосудах. От большинства этих сосудов сохранились лишь двойные донышки и между двумя их пластинками заключен тонкий золотой листок, в котором выскоблен рисунок, иногда оживленный раскраской. Хотя родина подобных золоченых сосудов, как надо полагать, Восток, однако большая их часть найдена в римских катакомбах. Самые древние из таких сосудов мифологическими и реалистическими сюжетами своих изображений свидетельствуют о своей принадлежности языческому времени. Из сосудов доконстантиновской эпохи, отличающихся тонкостью рисунка и шрафировки, всего один, принадлежащий Ватиканской библиотеке, украшен, несомненно, христианским изображением, и это последнее — опять-таки Добрый Пастырь. В этих произведениях древнехристианского искусства, как и во всех прочих, символические изображения предшествуют историческим, библейским сюжетам.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)