The art of the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia has existed for thousands of years, when Greek art was only beginning to stand on its feet, so that, in its rapid, victorious march of extraordinary height, to conquer Europe, Africa and Asia. Thousands of years have passed since then, and Greek art, despite the medieval interregnum and the desire of the new time to throw off its shackles, still enjoys a certain kind of predominance: remember the newest magnificent buildings of the whole world, still abundantly borrowing their forms from Greek orders, and programs studies in our art schools, in which now, as before, they draw and reproduce Greek statues. This has penetrated our consciousness, at every step you can find ornamental forms, directly or indirectly borrowed from Greece.

"True, freedom and beauty" - these are the concepts that are contested only by gloomy theory, to which Greek art owes the fact that it dominates the world. The art of the Greeks was able to reach the truth in imitation of nature. It was the first time, through a long struggle, to cultivate in him the ability not only to convey the human image in all the purity of its relations, with all the details of its body, in all the vitality of its characteristic movements, but also to depict its inner world with all the sensations expressed in its gestures and reflected in his mimicry: Greek art gradually taught us to see in extensive connected images no more than segments of the whole world of phenomena that convey them approximately true; he was the first to succeed, walking step by step, to invest in the images of his gods and heroes so much inner truth and so much persuasiveness that they compel the viewer to worship and self-purify them. Greek art first achieved freedom in its creations not only in the naturalistic direction, precisely conveying the anatomy of the body and the movement of the soul, but also in the independence of this image from all other spiritual forces and from the neighboring worlds of arts that influenced it in the epoch of its infancy. In its heyday, no art has ever been to such an extent national as Greek. It reflected only nature, and, moreover, as the Greek eye saw it, which was used to embody everything that it saw. The Greek gods, forests, mountains, springs, seas, celestial phenomena, the sun, the moon and stars, cities, finally, even virtue and vice (anthropomorphism) were personified. Greek art owes its eternal significance to a large extent to this free humanity. The beauty of Greek art undoubtedly lies in its truth and freedom; besides, like any artistic beauty, it consists in the complete agreement of the form with the content; at the same time, with respect to form, beauty lies in the expediency, by which the Greek artist, where necessary, subordinated liberty itself. All that has been said about the power of art to recreate the works of nature in its spirit, but with the elimination of accidents, which, in particular, reject it aside, all this is primarily found in the art of the Greeks. Some of their own sayings speak of this. In his best times, the times of complete independence, the private images that this art represented, imperceptibly became types in his hands, turned into exemplary figures of the whole world of people, heroes and gods from which they were taken. In order to attain the highest human beauty, Greek artists already from early on began to work on the definition of numerical relations between individual parts of the body. Changes in the taste of both individual artists and different eras were primarily expressed in changing these relationships. Of course, many of the greatest artists at all times worked on the basis of only their own observation, and this we could then calculate in their creations; but the fact that we could make such a calculation is proof of the expediency of the relations adopted by the Greeks. For all that, freedom and gentleness reigned within the limits of this expediency. Even Greek architects — and sculptors understand this by themselves — loved to take their torpor from ratios through minor deviations from geometric correctness, and in this way they sometimes barely noticeably tell their works the form of organic whole. Of course, there were no formulas for the depiction of the beauty of the soul that speaks from the heart to the heart; However, Greek art, in the animation of its works, surpassed everything that was created by more ancient peoples and former times: in its most mature creations, form and content are completely interconnected.

Idealism and realism, style and nature merge into one inseparable whole in Greek art. In the area of his tasks stand side by side, complementing each other, the ideal fantasy world and the historical world, or the world of the present and reality. The artistic imagination of the Greeks is closely connected with their poetry. The poems of Homer and Hesiod, the first to create for the Greeks the sky with his gods and the earth with its heroes, transferred to plastic arts their main material in a form as clear as crystal. With regard to the creation of images, poetry in Greece went ahead of the visual arts. In the same way, tragedy appeared in the field of images of higher spiritual excitations, while the painting and sculpture of the Greeks strove to achieve higher freedom in conveying emotional sensations and passions.

Greek art, especially sculpture, reproduced reality and grew directly from the competitions that united Hellenic tribes since the establishment of the Olympic Games. In running, racing, fighting physical strength and agility of the Greeks was tested. Winner expected high honors. Across the whole of Greece, gymnasiums emerged - institutions for exercise in strength and agility, where young people, after stripping naked, prepared themselves for solemn games. Due to this, the Greeks brought the body to perfection in proportion to its members, and the Greek artists early had the opportunity to study the male body from all sides and in all movements. The statues, which were erected in honor of the winners, were the closest and most direct evidence of the influence of physical exercises in depicting a naked body.

Finally, it is only in the history of Greek art that the artist first comes to the fore. In the big monarchies of the East and the South, the identity of individual citizens was lost in the vast mass of subjects, so their artists do not mention their history of art. On the contrary, in the small states of Greece, whose geographical fragmentation did not favor their unification, the civil independence of the individual grew on the ruins of the ancient monarchism. Already in the time of tyrants, in the VI. BC e., the first historically famous artists appear in Greece; along with the development of civil liberty, the number of artists' names and their significance increased. Soon came the master, whose names the posterity calls with reverence. And no matter how gradually and organically there was the development of Greek art (and no artist abruptly broke off his connection with traditions, but, standing on the basis of works of antiquity, he improved himself in the performance of particulars), the successive stages of the development of art are associated with the names of certain artists. development went on uninterruptedly and uncontrollably.

As a result, in the history of Greek art, a written, mainly literary, and artist history is given a place next to the history of artistic monuments . But since only a few of the monuments of Greek art are inscribed with the names of masters and only an insignificant number of these monuments can, on the basis of unquestionable sources, be recognized as original works of famous masters, the history of artists enters into the history of Greek art only as a department of literary sources for the history of monuments. arts that speak for themselves and which can be viewed as an almost independent branch of knowledge. To show the connection between the history of Greek artists and the preserved monuments of Greek art is one of the main tasks of artistic archeology. Johann Winckelmann, the father of the history of Greek art, who produced his main work in Dresden in 1764, based on the study of monuments, although he was not familiar with any of the original Greek works that were made available to us later. Winckelmann categorically stated that he did not consider his task to check and correct the history of Greek artists. Nearly 100 years after him, Heinrich Brunn, whose work appeared in 1857-1859, again took up the history of Greek artists, and, having collected all the previous works on this subject, he supplemented them with a long series of surviving works that he directly or indirectly attributed to certain masters or schools. Another generation passed, and Adolf Furtwengler (his work was published in 1893), again basing on the works of ancient Greek art and their copies, the number of which had increased in a completely unexpected degree, considered himself sufficiently advanced. , to attribute each of the ancient works, preserved in the original or in a copy, to one or another of the famous artists and put it in connection with certain of his creations, referred to in literary sources. Thus, he considered it possible to soon put "in place of the former pale and skinny picture a completely different, much richer picture of the history of Greek art." The fact that Furtwangler boldly ascribed the surviving works to famous artists does not prevent us from recognizing that his findings greatly enriched the historiography of Greek art.

If the study of the history of Greek artists after the appearance of the work of Brunn, who laid the foundation for it, established comparatively few new points of view, the number of Greek monuments, namely the original ones, has grown enormously. We consider it unnecessary to return to the excavations in Troy and the areas of Mycenaean culture; but it is necessary to mention, for example, the German excavations in the ancient fortified city of Olympia, undertaken under the leadership of Curtius and Adler in the years 1875-1881; about the German excavations of the End and Humana in 1878-1886. in the acropolis of Pergamum, the capital of Attalides, in Asia Minor; about the French excavations on Delos, the island of Apollo, and Delphi, the city of the most glorious of the oracles of antiquity: about the excavations made by the Greek archaeological society in the Acropolis of Athens and in Eleusis; about German excavations on Priene and in Miletus. Since the times of all these excavations, which caused a mass of original works to rest in life, resting in a deadly dream for 1.5 thousand years, the history of Greek art has completely changed.

At the end of the 2nd millennium BC. e. in the area later occupied by the Greeks, there were movements of peoples and resettlement of tribes, as a result of which the Hellenic settled on the places of Pelasgian or Achaean Mycenaean races. One by one, the Aeolians, the Ionians, and the Dorians of the Hellenic root came to the scene. The Aeolians occupied the northern part of the western coast of Asia Minor and the neighboring islands, especially Lesbos. Ionians, who probably came from Athens, settled the middle part of the western coast of Asia Minor, on which they founded the large cities of Miletus, Ephesus, Colophon, Klazomena and others, as well as the middle group of Aegean islands: Naxos, Delos, Paros, Chios and Samos. Then, after their travels, known as the “Dorian relocation” (about 1100 BC), the Dorians took possession of the Peloponnese and occupied the southern part of the west bank with Cnidus and Halicarnassus, as well as the southern islands: Kiefer, Crete, Melos, Fera , Kos and Rhodes. After a few more centuries, Greek colonies arose on the shores of Sicily and southern Italy, later known under the common name of Great Hellas. In the IX century BC. e. emerged poems of Homer. Beginning with the VIII century (776 BC. E.) Hellenistic chronology in the Olympic Games has been conducted. Since the beginning of the 7th century, the influence of the Pythian oracle at Delphi has spread, penetrating everywhere where the Hellenic language is spoken, and even further, down to Phrygia and Lydia, from where the kings send their gifts to this "navel of the earth." The history of Greek art begins, if not to take into account the legendary names, as well as the oldest of the inscriptions on the vases, only from the VI century. BC e. But since the VII century. BC e. You can trace the development of Greek art on the preserved monuments of various kinds, and some types of works of art, especially painted earthen vessels, take us back a few centuries.

The history of Greek architecture due to excavations has changed. Researchers such as Dörpfeld, Reber, Perrot and Shipiere, whose views so successfully brought Noak together, produce a Greek temple directly from the megaron - the hall of men for Mykene and Trojans (cf. Fig. 195). Thrones and tables for dishes (altars, altars), erected invisible, only imaginary gods, were the forerunners of temples. Only after the Greek heroic poems had finished elaborating the images of the gods, was there a need to build dwellings for them, like human beings. The sacred altar on which the sacrificial fire was lit was placed outside these buildings, in the courtyard. The sacred court (temenos, peribolos) was surrounded by a wall, which was sometimes interrupted by a monumental gate (propylon) in front. Actually the temple had the purpose to serve only as a home for the deity, a shelter for his throne. At first, the Greek temples, like the Mycenaean Acropolis already described by us, were built only from unfired bricks and wood, and their covering consisted of flat clay flooring along horizontal beams. The main peace of the megaron turned into the oblong hall of the temple, into cella, the actual home of the deity. A portico (pronaos), closed from the sides, and opening in front with two columns placed between the extensions of the longitudinal walls of cella (antami), was usually arranged also on the back of them, and in this case was called a despair (opisthodomos). But the piety and artistic flair of the ancient Greeks were not content with such an overly simple transformation of the dwelling of earthly rulers into a temple. In order to arrange festively decorated shelters for the gods, Greek architects surrounded the temple in the antes from all its four sides with an open gallery with a colonnade and a completely finished peripteric church (peripteros) was erected on a platform with several steps in order to raise it above the earth’s dust. Some scientists deny that the temple in the antes preceded the periphery, but it seems to us quite natural. Only at the end of the development of the form of the temple, its flat roof turned into a gable, which, perhaps, has long been used in private buildings in Greece, just as in Asia Minor (cf. Fig. 228). Low gables over the short sides of the building were almost always facing one to the east, the other to the west. It must be admitted that the roofs of the temples, like their columns, even in the finished form of the peripherical temple, were wooden at first, although they were lined with bricks and baked clay.

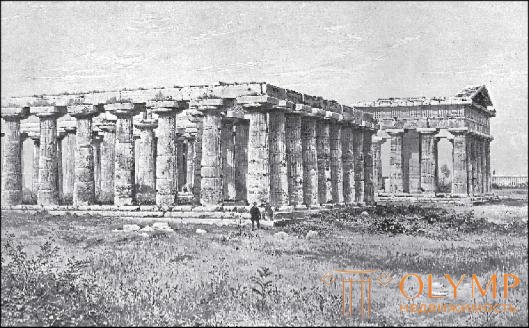

Fig. 247. The Basilica, or Temple, of Poseidon in Paestum. On the right is the temple of Ceres. Figure O. Schultz from a photo

Private changes in the Greek construction of temples are easiest to follow in the Doric style. The triglyph frieze, whose prototype, in all likelihood, was the above-described Tirinth dissected alabaster frieze (cf. Fig. 196), with the development of the surrounding colonnade, moved from the Antes to the entablature of this last and spread to all four of its sides. However, the Mycenaean column turned into a wooden Doric. The quadrangular plate above the capital (abacus) was kept. The round shaft has become echin from below. The chute beneath it, adorned with a wreath of standing, folded leaves at the top, retained its outlines and decorations in the era of the developed Doric style. But the columns, which had become thicker and consisted of whole tree trunks, according to their natural character, began to taper in the direction from the bottom up, and not from the top down, as in the Mycenaean art (Fig. 247). Wooden columns gradually gave way to stone, fluted. That in this case Egyptian protodoric stone columns served as a model for Greek architects (cf. Fig. 121), scientists as often claimed, as they denied; but in general it seems possible, if we take into account that it was in this era that Egypt began to enter into relations with the Greeks.

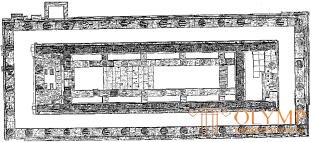

Fig. 248. Geroon's plan at Olympia. By durpfeld

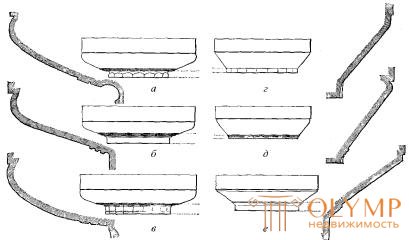

It is believed that in Geraona, the temple of Hera in Olympia, we have proof that this whole process of development went exactly in this way. Be that as it may, this sanctuary of Hera, the highest heavenly goddess, is considered the oldest of the Greek temples, from which remains are quite consistent with each other (Fig. 248). Its construction is quite fundamentally attributed to VII. BC e. Its surrounding colonnade, in contrast to the later temples, standing on a three-stage base, rises on the basis of only one step. It had 6 columns on the short sides and 16 columns on the long ones. It was of such considerable length, which later did not often repeat. Some of the columns made of marl limestone (poros) are monolithic, most of them are made of pieces; on one of them there are 16 flutes, but for the most part - already by 20. The entire course of the development of the Doric capitals is shown in capitals. In the more ancient, under a very convex ekhin, there is still a chute, but it soon disappears, and ekhin gradually takes on an almost straight profile (Fig. 249, a - e). It has been noticed that the wooden columns of the original temples from the 7th century began to be replaced by stone ones. Indeed, Pausanias, a famous Greek traveler II. n e., the best interpreter of which must be considered Wilhelm Gurlitt, reported that even in his time one of the columns of the rear portico of Garaon was wooden. The interior of this building is a very indicative example of how its division into three ships developed from the side chapels of the temple, and the walls of these chapels, which also served to support the ceiling, were torn down as soon as it was noted that the end columns were completely enough to support the ceiling beams. After this, the long hall turned out to be divided by two rows of columns, eight each, into a wide middle space and into two narrow side galleries. The original flat clay roof was in the 7th century. BC e. replaced by a gable roof of brick slabs with gable appendages (acroteries) of baked clay. Regarding the origin of these acterias of the pediment, Benndorf produced curious studies, confirmed later and continued by Trey. Acroteries should be considered as finishing the round front ends of cylindrical wooden beams, which, being visible from the outside, passed along the top of the Asia Minor wooden houses. The round shape of the most ancient gable acroters is thus explained by itself. Among the remnants of the terracotta architectural parts of the Olympic Geraona, a disc-shaped appendage of the roof was also found. With their technical design and unique coloring, these terracotta resemble ancient Mycenaean earthen vessels. The pattern, already somewhat in-depth, is illuminated with white, yellow and violet paints on a matte polished black or dark red background. There is a plastically rough round pole with sockets. Flat ornaments consist of circles, scales, chess and gear patterns. Eastern stripes and wavy stripes also slip. However, plant forms are not yet found.

Fig. 249. The development of the capitals of the columns of Gareon in Olympia (from a to e). According to Derpfeld (from the work of Curcius and Adler "Olympia")

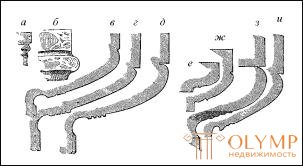

Fig. 250. Development of the capitals of archaic Doric columns: a - from the treasury of Atreus in Mycenae; b - at the Lion Gate in Mycenae; c - from Gareon to Olympia; d - from the temple of C in Selinunte; d - from the temple D in Selinunte; e - from the Hellenistic temple in Tiryns; Well - from the sanctuary of Cardiako, on about. Korff; h - from the temple of Apollo in Syracuse; and - from the treasury of the Syracusans at Olympia. By noack

In general, the appearance of a finished Doric stone church, in which we meet it at the beginning of VI. BC Oe., especially in ancient and southern Italian temples, the columns of the district gallery are striking, as if directly growing out of their common base, made of massive slabs, and equipped with 16-20 vertical segmental-like cross sections of recesses (spoons, flutes) with sharp edges (see fig. 247). Columns stand at a distance of 11 / 4-11 / 2 of its lower diameter from one another. Their height, with their increasing desire for greater harmony, varies between the 3rd and 4th lower diameters. Behind the core of the column is its neck, separated from it on the border of its upper piece by one or more narrow fillets and consisting of more ancient columns from the above-mentioned trench, decorated with a crown of leaves (fig. 250) and gradually disappearing during the 6th century. Over the neck of the column, several belts (kyma) encompass Echin, followed by a quadrangular tile (abacus), completing the capital of the column, and with it the lower supporting part of the structure. The upper part of the latter consists of two members - architrava (epistylion) and frieze (Fig. 251). The architrave, consisting of stone beams thrown from the axis of one column to the axis of the neighboring one, is smooth and ends at the top with a protruding shelf, under which, at a certain distance from one another, small bars are attached with conical drops on them similar to nail heads. These six drops hanging from each of these bars probably originated from wooden pegs used to hold the pieces together. The Doric triglyph frieze above the architrave consists of quadrangular surfaces alternately protruding forward and somewhat retreating backwards. Outstanding portions are called triglyphs; two flutes are embedded in the vertical direction, and the two halves of the flutes border their edges. Triglyphs are located just above the above bars with drops, which, as it were, form one whole with them. The retreating parts, the so-called metopes, are, in fact, smooth surfaces, but they are often decorated with sculptural work. Above the triglyphic frieze lies, strongly protruding, a cornice (geison), crowning the entablature; its lower horizontal surface, the so-called teardrop, is equipped, respectively, with each triglyph and each metope, with a row of quadrilateral oblong plates (mutuli, viae), set in drops. The cornice is completed with a strip of slightly curved profile. Similar eaves, but without plates with drops, border pediment. On the edge of the cornice (sima), behind which rainwater gathered, lion heads were planted, through which open mouths it could pour out. Acroteria, crowning the top and corners of the pediment, often had the form of animals, human figures or vessels. The extreme tiles of the brick roof of a building with its long sides usually had the appearance of palmettes. But the main decoration of the temples served as sculptural works, placed both on the metopes and on the pediment. The monumental sculpture of Greece immortalized its glory mainly by the execution of pediment groups for temples and other buildings.

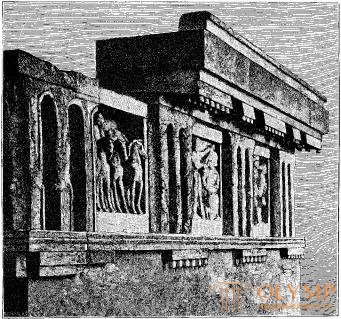

Fig. 251. The entablature of the temple of C in Selinunte. From the photo

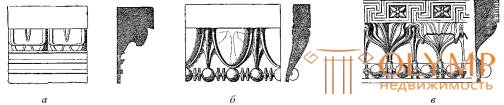

The impression of the Doric temple was largely due to the copious but elegant coloring. The finished Greek stone temple seemed very colorful. The building in general was of the same color, but some of its parts received full color, usually in red or blue. The excavations, however, did not confirm the assumption that Echin and abacus Doric capitals were always painted. But the curvilinear part of the eaves and straight bars of the architrave received colored ornaments in the early era, one - in the form of a wreath of wide leaves hanging down (fig. 252, a ), others in the form of a tape meander, simple or tortuous. The triglyphs were usually dark blue, and the metopes were left white or stained in their plane. But coloring everywhere served not to smooth the forms, but, on the contrary, to give them greater relief. Leaves hanging down to express their burdens that lies above them. The crowning bars were decorated with wreaths of palmettes (anfemii) of sculptural work or painted.

Fig. 252. Kimatii: a - Doric; b - Ionic; in - lesbos. By Baumeister

The interior of the large, main temple retained its division into three ships, which we have already become familiar with when describing the Olympic Gereon. The stone ceiling, divided into quadrangular recessed fields (a ceiling with cassettes, with Kalimmaty), with gold stars in the middle of each such field, painted in blue, hid behind it the wooden roofing rafters. The opinion that most of the significant temples received light through a hole in the roof, since the days of Derpfeld’s research and research, Durma has been considered untenable. As can be seen from the notes of Vitruvius, an ancient Roman architect and writer, the hyperal churches with open, bright space inside were only rare exceptions. Almost all the famous and famous Greek churches penetrated the light only through their monumental entrance doors; in the bright southern sun, this opening was enough to illuminate the inside of the temple.

But the main charm of the architecture of the Greek temples was not inside, but outside these buildings. The Hellenic abode of the deity produced the impression not of its internal, but its external side. Everything was geometrically commensurate, and this particularly distinguished the Doric temple. Here you can best see how this strictly geometric proportionality was softened and slight deviations from it were allowed, giving the impression of organic life. These include: replacing straight lines with a slightly curved one; quarrels, that is, small bulges on the horizontal beams of Doric temples; swelling (entasis) and thinning of the cores of the columns; slight inclination of the outer columns of the inside; the narrowing of the gaps between the corner columns and the irregularity in the position of the triglyphs that marked the axes of each column and each span between the columns and which in the developed Doric style at the extreme ends of the frieze seemed to shift from the axis of the column to an angle. The general form of the Doric temple is so harmoniously finished that even Bettiher in the "Tectonics of the Hellenes", in a work that was once famous and now outdated, explained the origin of the details of this form not on the basis of the history of their development, indicating everywhere their origin from wooden buildings, but on the basis of the theory of the ideal embodiment of abstract constructive and static laws. It remains, however, certain that the finished Doric temple represents in its architecture strict adherence to the constructive laws of gravity and its backwater and in certain forms expresses these laws in the clearest way. It also remains undeniable that the desire to arrange quiet dwellings of gods under roofs supported by columns led to a complete, most perfect development of buildings with columns and gables. But above all, it remains the truth that this artistic creation, no matter where it borrowed individual architectural elements, was a completely independent manifestation of the Greek genius. There is no architectural work in the whole world that would be like a Doric temple. As a whole structure, he had no predecessors to himself, and this structure in the totality of its parts was so striking that the art of humanity firmly held it to the present day.

In Southern Italy and Sicily, remains of ancient Greek temples are preserved, more significant than the metropolis of these colonies than in Hellas itself. In Paestum and Akraganta (Agrigento), these remains still hold; in Selinunte, Syracuse and other places, as you know, they have already fallen to the ground. Detailed scientific research conducted by Koldewey and Puchstein shed light on the history of the development of the Greek temple. The Doric temples of this part of Western, or Great, Greece, the construction of which, however, relates to the beginning of the sixth century, at one time gave the impression of austerity, even some heaviness. They have a front portico (pronaos), but the rear portico (opisthodomos) is still missing. Corner columns are not yet close together. Closely spaced, squat columns have a greater swelling on the rod (entasis). Low capital is strongly projected. The chute with a wreath of leaves under a capital is its permanent accessory. The triglyph frieze is somewhat narrower than the architrave. The gable is relatively high. The central temple at Selinunte (the so-called temple C) was built at the beginning of the sixth century; its columns are monolithic and have 16 flutes each. In the surrounding gallery there were 6 columns on the short sides and 17 columns on the long, so that it was even longer than the Temple of Hera in Olympia. Its portico is closed by the front wall, but the row of columns in front of it is double. Its entablature is exhibited in the Palermo Museum (see Fig. 251). A little later the northern Selinunte temple was built (the so-called temple D). It has 6 columns on the short sides and 13 columns on the long sides, so we already find here a normal numerical ratio. The portico of this temple is bounded laterally not by the antes, but by three quarters of the columns. The columns of the portico have 16 each, and the columns of the district gallery have already 20 flutes each. Megaron Demeter in Gagjer, near Selinunte, in which, together with particularly ancient forms of the cornice, we find in this last hint of the Egyptian trench, is curious about the open position of the entire sanctuary with its surrounding courtyard walls, entrance gates and an altar. The oldest temple of Paestum (see fig. 247), the so-called basilica, has 9418 columns; accordingly, an odd number of columns of its front side is divided into two parts inside the central row of columns. A little later, the so-called temple of Demeter in Paestum was built; its columns, number 6413, are already decorated with 24 flutes. Its portico, located inside the district gallery, is only half fenced with walls (in antis), and its front half consists of three free-standing columns (prostylos). If both of these temples were built really only in the middle of the 6th century. BC e., then their style still corresponds to the style of buildings that prevailed in the East at the beginning of this century.

Among the oldest Doric temples of this kind are the temple in Tarente, the sanctuary of Zeus in Syracuse, the temple of Apollo on the island of Ortigia, near this city, and the temple of the sacred well in Cardaco, on the island of Korf. But in Athens, remains of the oldest city temples are open. Previously, the later Doric temple, the magnificent Parthenon of Pericles, in the Acropolis of Athens, existed at least three temples dedicated to Athena Pallada: one built after the Persian Wars in the same place where the Parthenon flaunts, and the other two - before the Persian Wars near that point on which subsequently was the Erechtheion. The remains of the oldest of these ancient temples were opened and piled together. They also refer to the beginning of the VI.

The most ancient Doric temples formerly ranked (for example, Durm) a temple in Assos, on the Aeolian coast of Asia Minor. On its columns - from 16 to 18 flutes. There are no drops on the bars under the triglyphs and on the muduli. On the architrave, contrary to custom, there are sculptural decorations. Judging by the style of these jewelry, to which we will return, they should be of later origin. The oldest surviving Doric temples formerly considered the temple in Corinth. Without a doubt, it belongs to ancient antiquity, as it can be inferred from the fact that in its district gallery there are 6415 columns, as well as their heavy rods on 20 flutes and for the capitals, which are very prominently forward, still lacking a channeled neck (fig. 253) .

Fig. 253. Part of the temple in the Corinthian Kremlin. From photo (collection Merlin)

Treasures in Olympia acquaint us with a kind of buildings, very important for the history of architecture. Adler called them "architectonic gifts" dedicated to a higher deity. Their porticos with a gable supported by columns prove that the gables and colonnades did not constitute in Greece the exclusive membership of the temple-building industry. But one location of these buildings from north to south, and not from west to east, sharply distinguishes them from the temples. The states that built them ordered the manufacture of their parts from an indigenous stone at home and then sent them to Olympia, where buildings were laid out of them. The oldest treasury in Olympia - the treasury of the Sicilian city of Gela dates back to the beginning of the 6th century. It received in the history of construction art of great importance, since for the first time it was found out that, in the ancient style, the cornices of the pediment and sides of the building were often lined with colored terracotta.

Fig. 254. Terracotta decoration of the temple of C in Selinunte. By durpfeld

Fig. 255. The terracotta cornice of the treasury of the Gelois in Olympia. By durpfeld

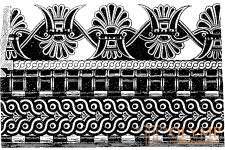

The painting of these terracotta in the temples has been going on since the beginning of the 6th century, to a certain extent in parallel with the ornamentation of earthen vessels. Терракотовые украшения вышеупомянутого древнейшего храма в Селинунте, как и коринфские вазы, расписаны прочными красной и черной лаковыми красками по бледному фону глины (рис. 254). Наряду с линейными орнаментами и простыми двойными плетенками здесь уже появляются орнаменты на мотивы растительного царства. Венок из свешивающихся листьев на верхней полосе карниза еще по-дорически полуугловато геометризован. Но пальметты в местах соприкосновения двойных плетенок уже имеют такую же форму, как и на милосских глиняных вазах; соединенные ряды, состоящие попеременно из пальметты и распустившихся цветков лотоса, которыми увенчана верхняя полоса карниза, имеют восточные формы, облагороженные эллинским чувством стильности. Меандры, плетенки, розетки и пальметты – главные составные части терракотовых карнизов сокровищницы Гелы в Олимпии (рис. 255). В одном из позднейших храмов Селинунта на терракотовом карнизе, между меандровой лентой и рядами лотосов и пальметт, находится шнур перлов (астрагал) почти в ионическом вкусе (рис. 256).

In addition to the Dorians, as it is known, the Aeolians and the Ionians are the main branches of the Hellenic people. Therefore, together with the Doric, the Eolic and Ionic styles arose immediately. The Corinthian Order, on the other hand, belongs to a later stupa.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)