The decisive victories won by the Greek nation over the Persian world monarchy in the first decades of the V century BC. e., once and for all provided the European peoples with the possession of the part of the world they occupied, and after their brilliant military exploits the Greeks committed great deeds in the field of transforming the human spirit.

For more than 100 years, Greek art in its organic development has strived for one great goal. Within the limits of the ideal tasks that the art of the Greeks served, this goal was to master nature through the possible transfer of its forms, and at the same time, to clean these forms from everything that was accidental and, thus, to create an artistic style corresponding to the inner and outer essence of each task. . The whole secret of the convincing power of mature Greek art lies precisely in the fact that it has always tried to unite nature and style, and not to put them together. This goal was gradually approaching even before the Persian Wars. If the last steps in that direction were taken precisely at the moment of national enthusiasm, which flared up brightly after the Persian wars, it only served to the benefit of the spiritual content of art, and if At that time Athens had decisively taken the lead in the movement both in the field of literature and theatrical art and in the field of figurative arts, this was primarily the natural consequence of the political primacy that fell to the city of Pallas Athens thanks to its leadership in victorious battles. But we should not lose sight of another reason for this leadership. The “Barbarians” of Souz and Persepolis, before their retreat, did not behave so cruelly in any city as in Athens. The buildings of the Acropolis turned into ruins; even in the lower town there was no stone left, and what was left of the destruction by the Persians served Themistocles, the winner at Salamis, as material for building fortified walls around the city and its harbor. Thus, the new era set Athens extensive, the greatest architectural and artistic challenges. The greatness of these tasks was heightened by social importance, their spiritual significance was heightened by the wealth of means that the victors could have; in other words, all the circumstances were such that they favored the achievement of Attic art after the Persian wars of such inner greatness and such external brilliance, to which it had never reached before or later.

Along with Attic art, the Peloponnesian still showed its peculiar strength. The main centers of art in the Peloponnese were Argos and Scyon, interconnected by some traditions; Compared to the purely social nature of Athenian monumental and ideal art, their art was civilized-limited, rooted in the lives of individuals, sought and produced unshakable rules for itself. Olympia, the main fortified city of Greece, could be proud not so much of its own artistic activities, as the number of works of art in it. As for Sparta, she was artistically poor. This harsh-haired city on the banks of the Eurota, which had acted as a rival to Athens in political life and finally won over them, seemed to have lost its artistic significance after Gitiada. Even after the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC. E.), Which brought Sparta for some time political supremacy in Greece, Athens immediately again stood at the head of the artistic movement of the new century. Argos and Sikyon in the Peloponnese did not abandon their former aspirations, and only Thebes, the main city of Boeotia, compared with them during its short-term political hegemony (371-361 BC) reached an independent, albeit short-term flourishing in figurative arts.

The Western Greeks of Sicily and Southern Italy, as well as the Eastern Greeks of the islands and Asia Minor, did not shy away from participating in the further development of Greek art, and perhaps it should be considered not by accident the fact that the greatest of Greek artists is the main activity which occurred in the era of the Peloponnesian War itself, were, with the exception of the sculptor Policlet, painters from Asia Minor and southern Italy.

After Greece has torn itself and again disintegrated into small states, it could have been mastered by weakened Asian opponents, gathering for this purpose with forces if, fortunately for European culture, the Macedonians, who were related to the Greeks by origin, borrowing their culture. In 338, Philip of Macedon put an end to Greek freedom, and his son Alexander in 330 ended the Persian monarchy. But Philip and Alexander felt themselves Greeks. Encouraging Greek art was one of the challenges of their lives. Of course, under the wings of monocracy, art was soon to embark on new paths, the direction of which was already noticeable among the great artists, contemporary Alexander. However, these artists, who were searched and chained to themselves by the Macedonian rulers, were brought up in the era of political and artistic freedom. Therefore, they belong, strictly speaking, to the heyday of Greek art, which ends with them.

The 200-year period of the prosperity of Greek art can be divided into stages. The preliminary flourishing to a certain extent coincides with the rule of Cimon in Athens, expelled from there in 461 BC. e. The first magnificent flourishing was the time of the rule of Pericles, who died in 429. The era of the Peloponnesian war does not constitute a special chapter in the history of art, having in many respects a transitional character. The second heyday begins from the IV century and, after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC), lasts for at least one generation.

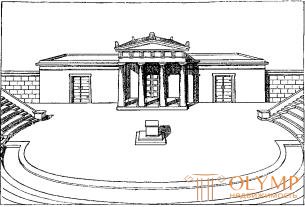

Fig. 306. Restoration of one of the oldest Greek theaters. According to Derpfeld and Reish

In the V century. architecture, whose works of creation of sculpture and painting were organically linked or strictly agreed, remained with the Greeks, if not guiding, then in the full sense of the word, the main art. In the development of the artistic side of the construction business, which alone is interesting for us, now, as before, stands at the forefront of temple and art. However, we, intending to keep up the ascending order, this time we begin our review with civil architecture, in the works of which, by the way, all the versatility, creative power and thoughtfulness of Greek architects are already revealed. Places intended for all kinds of public celebrations are especially indicative. Initially, it was natural, only aligned spaces under the open sky. Only over the centuries they turned into real art buildings, satisfying the increased requirements of protection from the weather, various amenities needed for placing people, and the pomp of the decoration.

After the studies of Dörpfeld and Reisch, our concept of the Greek theater has radically changed. Now we know that sublime stages belong only to Roman theaters, that in the Greek theater the actors, as well as the choir, performed on the round “place for dancing” (orchestra), in the center of which stood the altar (thymele). The orchestra was surrounded on three sides by seats for spectators. On the fourth side, opposite the seats for spectators, was a tent (skene), from which actors appeared on a flat arena. In fig. 306 - Restoration of the ancient Greek theater Dörpfeld with a view of the Skene, which is already a permanent structure here. Places for spectators, where it was possible, were arranged on the mountainside so that theater visitors could stand or sit one above the other; Such a device continued to hold on even after the seats for the spectators turned into an artistic one, although the building was still open-air, in which the rows of seats went one above the other and each upper row was longer than the one directly lying below it. Schenna, in front of which a wooden movable partition (proskenion) soon appeared for hanging decorations painted on it, gradually developed into a structure decorated with semicolumns and having on both sides an upstairs wing (paraskenion).

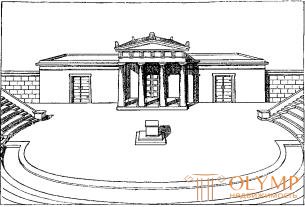

Fig. 307. Plan for Olympic Buleterium. By durpfeld

Of the surviving theaters of the 5th century, the theater of Dionysus, on the southern slope of the Acropolis mountain in Athens, was originally built before the Persian Wars, but only remnants of a circular orchestra, dug under the foundations of a Roman theater, reached us. From other theaters of the 5th century, such as, for example, theaters in Syracuse and Orope, only the ledges carved into the rock remained, which served as seats for spectators.

The buildings in which the musical contests took place contained enclosed spaces and were called Odeions . More Pericles built in Athens, a permanent Odeon, from which no traces have survived, there are only brief descriptions of it. According to Plutarch, in this building there were many places for listeners and many columns, and its sloping hipped roof ended with a pomeranian, which was made like the pomeranian of Xerxes' tent. The race for the boys' race in the race was called the stadium (stadion), because the length of its arena was equal to the stage (about 196.8 meters). On one of the narrow sides of the lists, which had the shape of a semicircle, as well as on both its long sides, seats for spectators were arranged, arranged in the form of ledges. Hippodromes, buildings for horse and chariot races, had the same plan, but much larger. All surviving buildings of this kind belong, however, to later centuries and are of little interest to the history of art. In the V century. they gave the impression of more natural, cleared with human hands and adapted for this purpose areas, than buildings. In the same way, the places where young men prepared for competitions, gymnasiums and Palestrés, which later turned into magnificent buildings with colonnades, courtyards, and halls, didn’t have any particular architectural processing at this time.

More significant remnants survived from buildings intended for public gatherings and meetings. We can figure out for ourselves the concept of boolevteries, in some ways the town halls, since Olympia's boolevterium came to light again (Fig. 307). It consisted of three large separate halls, which on the east side were connected by one common Doric portico. The middle hall was square in plan. The north and south halls were longer than average; their eastern, short side had the shape of a semicircle, and on the western front side the hall opened with a portico with a span and columns set between the antes; along the entire length in the middle of each hall there was a row of columns dividing it into two ships. The northern hall, as Derpfeld concluded for the capitals of one of his antes, was built in the 6th century, and the south, in which Doric capitals are similar to the capitals of the Olympic Temple of Zeus, in the 5th century. The middle hall and portico were built during the later restructuring of the building. Excavations at Olympia also led to the discovery of a plan of one of the pritanees , the state palaces of Greece, in which the sacred center of Hestia was located. Complete reconstruction in the Roman era, of course, buried the original building under itself and cut it in many directions. It can be seen, however, that its shape was square, 100 Greek feet (one plefron = 32.8 meters) in each side. Apparently, in this building led a portico with two columns. Symmetrically located halls, galleries and courtyards adjoined the square hall, in which, probably, the altar of Hestia was located.

In many significant cities there were public buildings for peaceful conversations, "talkers", as we would call them now, or leshe, as the Greeks called them. They were often decorated with paintings, and in their construction they probably resembled the stands that served for walks and for public readings. Usually they consisted of a wall and two rows of columns in front of it, from which the outer one went out into the square or the street. In Olympia, remains of the Doric, decorated with painting "stoa poikile" and the large Echo of the Echo gallery located behind the gallery, which in the 4th century closed the eastern side of Altis, the sacred Acropolis stronghold. Greek markets were also often surrounded by columns with porticoes. The same porticos stretched behind the theaters. The surviving remnants of these dual porticoes belong almost exclusively to later centuries. But, in any case, they were still in the V century, together with artificial, having a definite, correct plan, city streets. After Themistocles had walled the Athenian harbor of Piraeus, and Pericles had connected it with the city by long walls, it was necessary to rebuild Piraeus itself in order to turn it into an exemplary, well-located walking place. The plan for this restructuring was compiled by Hippodam Miletsky, who also planned a new gulbushche of the colonial city of Furies in Lower Italy (in 441), which intersected four or three widths at right angles. The third main gulbische, arranged according to the Hippodam plan, was located in the city of Rhodes (407); it girded his harbor in a semicircle, like a theater hall.

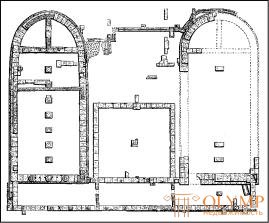

Fig. 308. Sikiontsev's treasury in Olympia. By durpfeld

Residential buildings on the streets of such "artificial" cities had common demarcating walls, but from the front they, as a rule, did not have artistically designed facades. In contrast to the Greek temples in the residential building, the gallery with columns was always turned not outward, but inward; not a single house, which claimed to be the dwelling of a nobleman, could do without a courtyard furnished with columns. But if, as it seems likely according to the studies of Bié, the later Greek house occurred in a straight line from the Mycenaean royal palace through the development of its court and the weakening of its value as a megaron, then the Greek houses of the classical V century. should be considered a certain intermediate stage of this transformation of dwellings.

The middle between civil buildings and temples is occupied by so-called treasuries, which were erected in various cities, such as in Delphi and Olympia. We have already become acquainted (see fig. 254, 255) with the oldest structures of this kind in Olympia; Sikiontsev's treasury, which could be restored better than all others, is, according to Derpfeld, in the middle of the V century (Fig. 308). It had the appearance of a temple in antis, with a simple portico on two Doric columns that stood between the projections of the longitudinal walls. The elegant, noble in form, but not very sloping profile of the cushion of the capitals of the columns of this building indicates the time of its construction.

But the most important for studying the further development of architectural forms remains the temple. Regarding the plan and construction, the Greek temple at that time has already experienced the main time of its evolution. Significant deviations from the established norms were met only to the extent that local conditions of the soil or features of one or another deity worship demanded. Small differences, such as changes in proportions, number and arrangement of columns, occurred most often from the whim of the architect or his customer. As a matter of fact, none of the Greek temples is quite like the other. The development concerned only certain forms and proportions, as, for example, in the Doric order it represents to us the transition from significant thinning of the column core and removal of the cushion of capitals through a noble elastic range to dry straightness (see Fig. 249), and in the Ionic Order the transition from complex the composite form of the capital to the later, normal, gradually becoming more and more subtle. Sometimes, along with this, there were deviations of a local character, such as, for example, attempts made in Athens to bring the Ionic and Doric styles closer together.

Fig. 309. Natural stipules of acanthus. By Meirer

Fig. 310. Natural acantha bracts. By Meirer

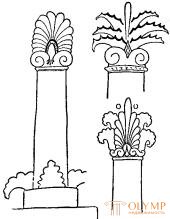

The most important event in the history of Greek architecture in the 5th and 6th centuries. BC e. there was an introduction to the use of the third, Corinthian order of columns. Hand in hand with the development of the Corinthian style, there was an introduction to the Greek ornamentation of the acanthus leaf. That in this case it is really about the plant "bear's paw", as it seems at first glance, and moreover about its bract, Meirer brilliantly proved against the theory, which took acanth only for the modified form of the Egyptian lotus flower. It is impossible not to consider progress that the Greeks for some time sought to enrich their borrowed from the outside, rather scarce ornamental motifs, limited to the meander, weaving, wavy lines, lotus and palmettes, introducing into the ornamentation of their native, natural forms of the vegetable kingdom. The introduction of acanthus was the happiest and most fruitful attempt of this kind. Acanth began to replace the palmette everywhere, from which it differs in external outline in that the notches between the teeth of its leaves are rounded, not as sharp as the palmette. First of all, this form appeared on top of gravestone stelae, both real and depicted on vases, in the latter case, moreover, at the stem and the foot of the stele, which includes an acanthous jewel "like a bract." Very early, the acanth also began to replace the palmette on the ridge of the roofs of temples, such as in Olympia; he soon penetrated, alone or in conjunction with palmettes, into floral belts; spiral antennae clearly show us how “the phenomena of germination on the stem of a plant” transform into the acanthic ornament (fig. 309312). We see the most important use of the acanthus leaf in the ornamentation of the Corinthian capitals, the invention of which is attributed to the sculptor Callimachus. The need for capitals, which would be more luxurious and fuller than Doric and at the same time not as one-sided as the Ionic one, designed only to be looked at from the front, became urgent in the second half of the 5th century, especially since the then taste leaned towards softer and free forms. The main cup-shaped form of the Corinthian capitals had its prototypes in numerous protocorinthian capitals of ancient Egypt. A crown of leaves, standing vertically around the bowl, is found on Egyptian capitals, and on the Theban capitals of the new period of the Egyptian state four leaves have already appeared, rising from the lower crown of leaves to the edges of the bowl and twisting upward in the form of narrow curls (Fig. 313). Replacing the Egyptian leaves, which in the lower crown were only painted, the plastic image of the acantha gave the Corinthian capitals an original character. The quadrangular upper plate (abacus), to which four snails, a stem, twisting upward like a shell, rise, finally gives the impression of originality to the developed Corinthian capitals (fig. 314). A thick ring, often shaped like a band of pearls, separates the bowl from the rod. The crown of acanthus leaves doubles. Eight top leaves out of the intervals between the bottom eight. In the space between every two upper leaves, it rises from them along a stalk that resembles a reed; it bends, twists and, forming a curl at the top, touches it to the curl of a neighboring stem; in addition, between these short stems and the edge of an abaca concave inward, an ornament in the form of a fan-shaped flower or rosette is placed (fig. 315). In all other respects, the main difference between the Corinthian style and the Ionic close to it is only in the cones of a wavy profile, which sometimes were placed instead of the dentils under the crowning cornice, as it were, to support it. Due to the very nature of their taller, capitalist-looking capitals, Corinthian colonnades, which were notable for the distance between the columns, seemed to be taller, more open, and lighter than the Ionic ones.

Fig. 311. Reproduction of acanthus in the Greek painting of vases and on gravestone steles. By Meirer

Fig. 312. Ornamentalized acantha bract in Erechtheion. By Meirer

Fig. 313. Egyptian cup shaped capital of the New Kingdom. By durmu

Fig. 314. Corinthian capital of the Temple of Apollo in Figalia. By durmu

Fig. 315. Developed Corinthian capital of Epidaurus. By Meirer

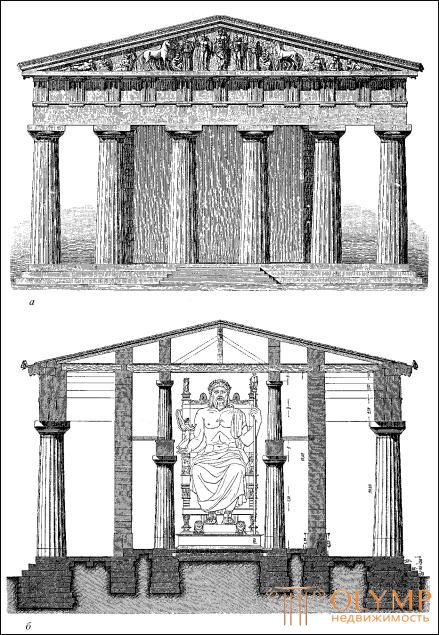

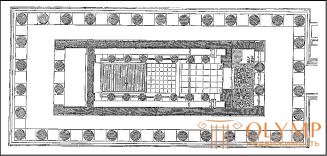

The first large temple erected in Greece after the Persian Wars and completed in the spirit of the new time was the Doric temple of Zeus at Olympia (Fig. 316 and 317). The ruins of this temple and its description by Pausanias give us the opportunity to quite clearly imagine all its former glory. It is especially important to us as a typical Doric temple of the first blooming pore of Greek art. The builder of the Olympic temple is considered to be Libon from Elida, a local artist as opposed to others who worked in Olympia.

The cella of the temple was divided into 3 naves by two rows of columns of 7 in each.

Pronaos and opisfod each had 2 columns between the antes and opened into the gallery surrounding the temple, in which there were 6 on the short sides and 13 on the long sides. In a rather strong refinement of the columns and in the width of their abacus, the remainder of the archaism is shown; pillow capitals are high but soft and clean in shape. The affiliation of this temple to the epoch of preliminary flourishing of Greek art is expressed more in its sculptural decorations, which we will talk about later than in its architectural forms. Next to it, as the Peloponnesian building of the last quarter of the 5th century, the original Dorian temple of Hera in Argos, rebuilt in Doric style, should be erected , which was erected after a major fire in 423 by the Argospse architect Evpoleme according to the same plan, but, as the excavations showed, with more graceful forms of individual parts.

Fig. 316. Temple of Zeus at Olympia. On the restoration of Dörpfeld: a - facade; b - cross section. By Derpfeld and Adler

Fig. 317. Plan of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. By durpfeld

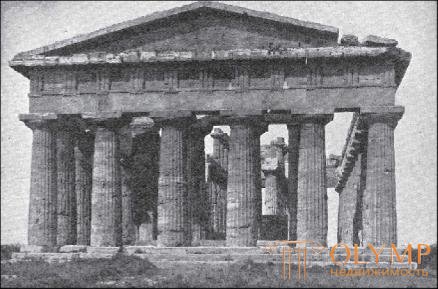

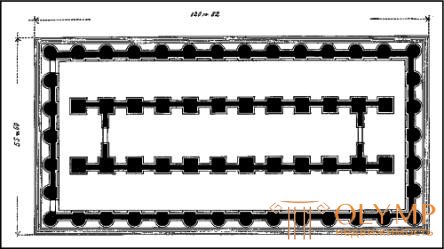

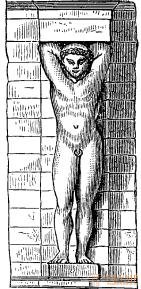

A number of Doric temples of southern Italy and Sicily are quite similar in shape to the above. Of these, we point out, first of all, the temple of Poseidon in Paestum (Poseidonius; fig. 318), which, in any case, even if we attach importance to the opinion of Koldewei and Puchstein, who believe that it was built later than the Athenian Parthenon, was erected after the Persian Wars . The temple had 6 columns in the short and 14 in the long sides, and inside it was divided into 3 naves by two rows of columns, above which was on the second row. This is the only one of the temples of the ancient world, from which the upper tiers of columns have survived. The weathered limestone from which it is built, from the time it lost its painted plaster; the nature of the grim force of closely spaced columns with 24 flutes each; the massiveness of its capitals, which are still distinguished by a large carrying forward and crowning the cornice; the simplicity and clarity of the distribution of gravity — everything gives this temple its peculiar greatness. The great temple of Zeus in Akragante (Agrigento; fig. 319) gives us a clear idea of what the Greeks called pseudoperipter. It is not surrounded by a colonnade, as peripherical temples, but by massive semi-columns leaning against the walls of cella on all four of its sides, 7 on each of the short sides and 14 on each of the long, with intervals of sufficient size to fit them. adult. The roof of the temple was supported from the inside by respectable pilasters with naked male figures attached to them - Atlantes or Telamones (Fig. 320). One of these Atlanteans, about 8 meters high, in the forms of which mature archaism manifests itself, is put back in its former place. Of the Doric temples in Akragante, one should mention the temple of Juno Lacinia and the Temple of Concordia: they have 6 columns in short and 13 in long sides. The Temple of Concordia and the unfinished temple on the edge of the hollow of Segesta belong to the most preserved ancient sanctuaries. The Temple of Athena on the island of Ortigia, in Syracuse, which had 6 columns on its short and 14 on its long sides, can be considered one of their monuments of a fully developed Doric style; its columns are highly refined and have 20 flutes each. In Selinunte to the V c. temples of both southern hills; the temple of Hera E on the eastern hill, judging by the style of the sculpture of his metopes, should be recognized as the same age as the temple of Zeus in Olympia.

Fig. 318. Temple of Poseidon in Paestum. From the photo of Zommer

Fig. 319. The plan of the temple of Zeus in Akraganta. By Durmu

On the Ionian coast of Asia Minor, soon after the Persian Wars, vigorous building activity also began. The large Ionic temple of Artemis at Ephesus (see fig. 227), spared by the Persians, was completed in its original form by the architect Peonius and the work manager Demetrius in this era . A large Ionic temple of Didim Apollo in Miletus, destroyed by the Persians, had to be built again. This building was made by the same Peony with the help of Daphnis, who managed the works. However, most of the architectural remnants of this huge brilliant temple, which had a double colonnade around itself, and, therefore, belonged to dipteras, bears the character of post-Alexandrian time. Apparently, the building was left unfinished. Of the other Ionic structures, you can point to the Nereid Monument in Xanthus, in Lycia, although there are still disputes about the time of its construction. As far as can be judged from the ruins, it was a small temple, standing on a high foundation, with four widely spaced Ionic columns on the short sides and with six on the long ones. There was no frieze in its entablature, so here, as in Assos, only an architrave decorated with plastic images separated the columns from the denticule cornice. From the Nereid Monument in Xanthus, only the bare foundation was preserved. His rich sculptural decorations are in London, in the British Museum.

Fig. 320. Atlas from the temple of Zeus in Akragante. By Michaelis-Springer

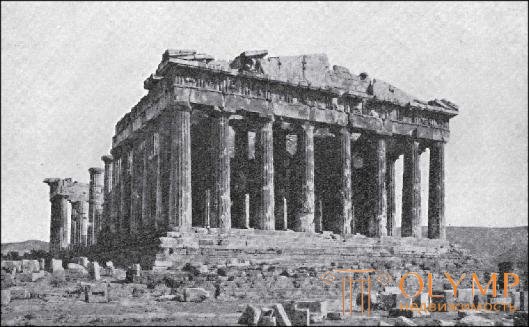

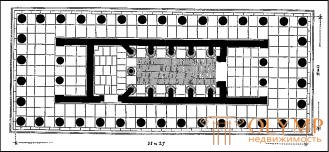

The purest atmosphere of art V in. emanates from Attic architecture - the art in which the power is combined with grace, strict correctness - with freedom, harmony - with pomp. Art has already managed to completely mature and throw off the last shackles, when Athens needed its services for important buildings. It is hard to believe that the Athenians, after the fire that devastated their Acropolis in 480, left its temples in ruins for 10 years. First of all, it was necessary to restore the old Pisistratovsky temple, located on the northern edge of the Acropolis Mountain and dedicated to the defender of the city, Athena Pallada, and at the same time, Poseidon Erechtheus. Even under Kimon, if not under Themistocles, construction was begun, further to the south, on the top of the mountain, a new temple of Athena Pallas, Parthenon; we are talking about the ancient Parthenon, which was longer than the second temple with this name, which received worldwide fame. It was never completed, it was demolished, when Pericles, on the advice of the great sculptor Phidias, commissioned the architects Iktin and Callicrates to build a new temple of Penteli marble in its place. This building was started in 447; in 434, the temple was ready and was a miracle of noble beauty and serene grandeur. He stood for 2 thousand years without losing his essential features, although he was disfigured by outbuildings and superstructures, turning him into a temple, now into a church, now into a mosque and, finally, into a powder shop, until in 1687 the Venetian bomb . But the Parthenon still stands half full, and its ruins still speak of the glory of Pericles, Ictinus and Phidias (Fig. 321). He did not belong to the largest temples of the ancient world; its length is about 70, width is 31 meters; but he made a charming impression of the proportionality of his parts. With a whole, surrounded by only one row of columns, 8 on each of the short sides and 17 on each of the long, it was a Doric temple, distinguished by an extraordinary nobility of proportions. Large pediment groups successfully filled the triangular spaces of the gables. Metopes on all its four sides were decorated with reliefs. The dark blue triglyphs stood out favorably from the red background of the metopes. Its cordial pearl (astragalus), which separated the crowning eaves from the triglyphic frieze, was its ionic feature. The capitals of the columns slightly thinning upward and swollen (entasis) had an ekhin slightly curvilinear, almost straight profile and only a little abacus protruding forward. Zella already outside was conspicuous features. She stood two steps above the district gallery, which was placed on a stepped base; her pronaos and despair opened into this gallery each of a series of free-standing columns. The frieze above these pillars, like the Ionic Zofora, was decorated with sculptural images and continued on all sides of the cella that opened onto the district gallery, thus having a length of 159.45 meters. The building of the temple itself consisted of cella, facing the entrance, as always, to the east and divided in this temple by two rows of Doric columns, 9 in each, into 3 ships, and the back room, in which the ceiling with its cassettes was supported by 4 columns of Ionic character. The Parthenon differed from most of the former and later Greek churches by the harmony of its parts, the grace of size, the slight scale of the straight lines - qualities that are felt more by the eye than are descriptive. Thanks to these qualities, the Parthenon, to which we will return to the plastic decorations, is considered the most classic of all classical buildings.

Fig. 321. The ruins of the Athenian Parthenon. From the photo

Fig. 322. Plan of the Temple of Apollo near Figalia, in Arcadia. By Durmu

Fig. 323. The capital of the columns and the frieze of the temple of Apollo near Figalia, in Arcadia. By durmu

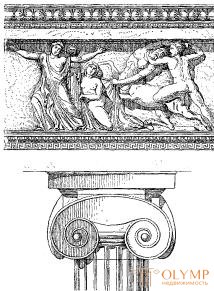

The main builder of the Parthenon, Iktin, endowed other cities with important structures, two of which, the temple in Eleusis and the temple of Apollo in Bass, retained their glory to this day. The church on the coast of the blue bay of Elivzis, the so-called Telesterion, has always been distinguished by its original form: it was a square in the plan with columns, resembling a similar building of the Egyptians and Persians. After it was destroyed by the Persians, Iktin received in 440 an order to erect it again on a larger scale, compared to the former, and from that time its interior was a grove of 42 (687) columns. Doric portico from its eastern side was added only at the end of the 4th century by Philo. The plan of the temple of Apollo near Figalia, in Arcadia (Fig. 322) was invented by Iktin shortly after 430. There was originally a small, simple temple here. Iktin, in gratitude for the cessation of the plague that raged in this healthy, fresh, wooded area, surrounded the old temple with a new building with a colonnade. It is remarkable that the new temple was built at a right angle to the old one, so that with its short face it was not facing east, like this last one, but to the north. As a result, the old temple of cella entered the back of the cella, but so that when its northern wall was demolished, a special entrance was made on the eastern long side of the new temple. This new temple was an oblong peripter with 6 columns in each of the short and 15 in each of the long sides. The columns were in it even more straightforward profile than in the Parthenon. The development of style in this respect took place in an unbroken sequence. Inside the cella was 5 side chapels on each long side. The protrusions of the wall that separated the chapel from the chapel, each ended with an incomplete column of the Ionic order, namely, 3/4 of the column. Капителям этих неполных колонн со всех трех их сторон была дана форма лицевой стороны ионической капители, для того чтобы при взгляде на них сбоку они не представляли свесившихся и свернутых подушек. По своим огромным волютам и двучленным киматиям без всякого валика эти капители считаются представительницами первоначального, западного типа ионического ордена (рис. 323, внизу). Но в том месте, где новая постройка открывалась в старую небольшую целлу, находилась колонна с коринфской капителью – быть может, самой старой коринфской капителью, какая нам известна (рис. 323, вверху). Ее чашеобразная форма еще не совсем замаскирована лиственным венцом. Нижний двойной ряд аканфовых листьев окружает только нижнюю часть чаши, из которой по углам поднимаются вверх стебли, сопровождаемые до некоторой высоты более длинными аканфовыми листьями. Внутри храм был обильно украшен пластическими произведениями. По антаблементу ионических неполных колонн целлы тянулся знаменитый скульптурный фриз, находящийся теперь в Британском музее. В совокупности всех частей этого храма был виден большой шаг вперед в отношении большей свободы и большего разнообразия всех деталей. This was probably the first temple in which columns of all three orders were simultaneously applied.

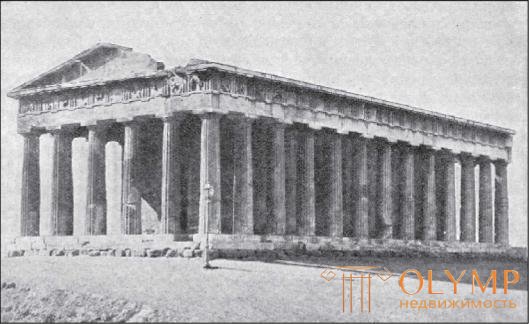

Fig. 324. Temple on the Market Square in Athens (Fezion). From the photo

To the most ancient Doric temples of the second half of the 5th century in Attica, in addition to the Nemesis temple we considered in Ramna, the temple of Athena at the foothills of Sunia and the temple of Penteli marble built on the Market Hill in Athens, which is remembered to everyone who saw it as best preserved than any other Greek temples (Fig. 324). The original name of his temple, Theseus (Fezaillon) turned out to be flimsy; the assumption that he was devoted to Hephaestus also raised objections, although Sauer, in his work, defended this opinion. By its construction, this building with a district gallery, which has 6 columns in the short sides and 13 in the long, is nothing special, except for the district arcade greater than the usual depth of the front side.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)