After the death of Alexander the Great, Persia went to the Greek Seleucids, who soon, approximately in the middle of the 3rd century. BC e., were overthrown by the Parthian Arsakids who swept from the north. At that time, on the Tigris, opposite Seleucia, Ctesiphon "plentiful treasures" emerged, serving as the winter residence of the Parthian kings of Scythian blood. The Parthian kingdom, which flourished for 475 years, was a strong stronghold in the east against the coming dominion of the Romans. Only in 226 AD e. the revolt of the indigenous Persians who liberated their country, beginning with the south, put an end to the harsh domination of the Parthians and their alien cult of the gods. The ancient sacred fire blazed on new altars. Sassanid Ardashir I (Artaxerxes) was the founder of the knightly New Persian state of Sassanids, which in its numerous wars with the Western and Eastern Roman emperors defeated them, until finally in 641 did not fall under the onslaught of the Arab Mohammedans.

For almost nine centuries of dominion over ancient Persia, first Arsacides and then Sassanids, the country of the palaces of Persepolis and Susa had their art. The ruins of the magnificent buildings erected then in this country testify to the wealth and luxury of its sovereigns.

Unfortunately, these buildings, published and described by Flandin and Costa, Texier and Delafoy, cannot be timed to specific years. However, after Perrault and other writers denied the opinion of Delafua, who believed that the domed buildings in Firuzabad and Servestane belong to the 6th century. BC e., it was possible to determine, albeit approximately, the time of the emergence of the three main groups of buildings in which the Hellenistic or Hellenistic-Roman architectural style responds or premonitions. The end of this time, or the beginning of the Sasanian epoch, belongs to those of the ancient domed structures of its own Persia, which Delafua attributed to the time of the Achaemenids. Later buildings with vaults and most of the reliefs on the rocks appeared already at the Sassanian time.

The oldest of the buildings, proving the penetration of the Hellenistic-Roman style in Persia, is the temple of the sun in Kanjavar, near Gadaman, ancient Ecbatana. His peristyle, representing a strong mix of styles, can be attributed to the 1st century. n e. The columns of this gallery have Attic-Ionic bases, smooth trunks, and Doric capitals with Corinthian abacus.

The palace in the Kremlin Al-Gatra (Gatry), in the Parthian then Mesopotamia, was built in the II. Three huge circular arches lead from its facade to high porticoes covered with box-shaped vaults. Four small circular arches located on the sides and between the large arches lead to smaller rooms. The entablature piece represents a frieze adorned with acanthic leaves between ancient Persian stepped teeth. But the most remarkable here are the numerous human heads that adorn the archivolts and capitals of pilaster. They are sculptured in the spirit of Greco-Roman art and resemble the barbaric custom of exposing the heads of dead enemies at the gates of the fortresses. The whole facade gives the impression of the architecture of the Roman triumphal arches, distorted in barbaric taste.

Then III. belong to buildings with vaults in the heart of ancient Persia, which grew on entirely different grounds, but were in any case palaces of Persian sovereigns. Architectural monuments Firuzabad - the ancient ruins in Servestan. The entrance hall in these buildings, covered with a huge vaulted vault in its entire width, opens outwards in the form of a circulating portal; it is followed by halls covered with domes; even further lies the large quadrangular courtyard, surrounded by halls with chest-shaped vaults. Regarding the history of development, it is interesting to overlap the above-mentioned front quadrilateral halls with high oval domes, the transition to which from a rectangular base is made up of corner niches that are predecessors of real, regular pandantivas. We have already seen that similar problems with flat domes led to the same solutions simultaneously in Italy, Syria and Asia Minor (see Vol. 1, Fig. 512). But in order to serve as models for these new Persian domes, the Roman ones, as Shnaze believed, for example, are as unlikely as Delafouis's assumption that all European dome structures originate from the New Persian dome system. Most likely, the Mesopotamian dome architecture, which Strabo talked about, won itself, on the one hand, the Hellenistic West, and on the other - the Persian East, and then the highly highly domed form, which in Ancient Assyrian monuments was a characteristic Mesopotamian feature, moved from New Persia in the building art of Islam. The arches in the buildings of Firuzabad and Cervestan are sometimes too high, and since their supporting pillars protrude within the span, they assume, at least in appearance, that horseshoe shape, which was later developed in the architecture of Islam.

In the Firuzabad Palace (fig. 547) there is only one front portal hall, but behind it there are three dome halls, the domes of which are elevated only from the inside and seem low from the outside. On the contrary, the serviestansky palace, built later, has three portals, but only one main hall, the dome of which, if you look at it from the outside, stands above the building in the form of a large semi-oval. The walls of the Firuzabad Palace contain many niches, the framing of which is a cornice borrowed from the ancient Persians. Outside, the long sides of this palace are decorated with fake arches, foreshadowing medieval arkatury. The half columns between the arches have neither bases nor capitals; a simple strip of teeth, similar to the teeth of a saw, crowns the wall above the main eaves.

Fig. 547. Section of the Firuzabad Palace. According to Flandin and Costa

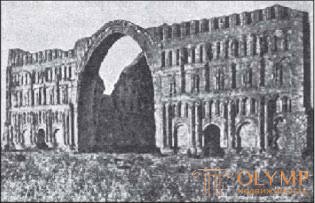

The most important of the structures that give us the concept of the art of the Sassanian time is Takht-i-Khosru in Ctesiphon, which is one huge hall, perhaps serving for the audiences of King Khosrow I (531-579 AD). From this building, a wall of a three-tier facade (Fig. 548) has been preserved, in which, like in the Firuzabad Palace, there is in the center, instead of the gate, a huge arch that extends above the wall and continues inside the building in a hall covered with a giant vault. For the sustainability of the extensive brick facade of the facade, the upper tiers of the wall somewhat retreat inward; in addition, to give the wall greater strength are double rows of arcades, thanks to which the three tiers are divided into two floors, so to speak. In the vertical direction, the lower tier is divided into parts by pairs of columns with trapezoid capitals, which reflect Byzantine influence, and the second tier - by simple near-wall columns. The arcs of arcades are simple circular ones, but due to the fact that the pilasters carrying them on themselves protrude inward, they produce the impression of horseshoe-shaped ones. Remarkably, one of the walls inside the building is cut by a real pointed arch. Thus, we clearly see here the general continuation and further development of the Firuzabad servetan style with some individual innovations, which were later perceived and developed further by both Islamic and Christian art. Delafua considered it probable that this building, on whose bricks no slightest trace of glaze was preserved, initially had a metallic luster from the silver brought on it, while floor carpets and wall curtains imparted a beautiful and cheerful appearance to the interior of the building. Written sources mention the Sassanian wall painting, but its echoes reached us only in the tissues of that time and in the late Persian miniatures.

Finally, the building in Rabbath-Amman, which we, together with Delafoua, recognize as the latest surviving Sassanian structure, represents, instead of the elevated circular arch of the entrance to it, an already pointed arch; on the lancet vaults, a huge Sassanian bridge rests in Schuster. Thus, we see here the transition to the time of Mohammedanism.

Fig. 548. Ctesiphon Palace. By delafua

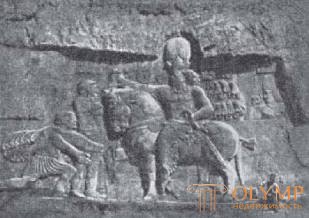

The sculpture of Arsakids and Sassanids is not as independent as their architecture. At first glance, it seems to be the offspring of Hellenistic-Roman sculpturing to which the Arsacid relief on the rock in Begistoun responds, depicting the Parthian king Gotharces I (45-51 AD), galloping on a horse and crowned with the goddess of victory, even more than similar Sasanian reliefs, in which, for all their affinity with the sculptural works of the late Roman Empire, some original features are already beginning to appear. A number of these reliefs begins with colossal images of the exploits of Shapur I (240271 AD), sculpted on a rock not far from the cave tombs of the Achaemenid kings in Nakshi Rustem (see fig. 236). Here, first of all, two horsemen in rich royal attire, standing against each other at such close distance that their horses touch one another with their foreheads, are striking. Riders hold a hoop between themselves with their right hands. The slain warriors lie under their horses; behind the junior rider is a servant, chilling him with a veil of the vane. On the senior rider - the royal crown. This relief depicts, apparently, Ardashir I, making his co-regent his son, Shapur I. To the right of this relief, the triumph of Shapur over the emperor Valerian is very vividly represented (Fig. 549). The second series of reliefs glorifying the acts of Shapur is in Darab Gerda, between Shiraz and the sea. The huge size of the main scenes are closed, sometimes on both sides, several, one above the other rows of reliefs of a smaller scale. Here we see images of wars, the conclusion of peace treaties, triumphal processions and hunting scenes.

Fig. 549. The triumph of Shapur I over the emperor Valerian. Sassanian relief on the rock. By delafua

The last times of the Sassanids, by the time of Khosrov II (591628), include the sculptures of Tage-Bostan, near the city of Kermanshah, on the present Turkish-Persian border. Tage-Bostan is a niche with a circular vault, on the outside of which, at the rounding, two winged goddesses of victory are depicted, inside, on the back wall, a king’s statue is carved and above it is a symbolic image of his accession to the throne, and on both side walls Adventure. The general character of these sculptures testifies to their Hellenistic-Roman origin. No matter how rude their execution, according to the language of their forms and the motives of the movements represented, they nevertheless belong not to primitive, infant art, but to art borrowed from being in decline. The fact that they have a new, echoes the medieval era.

Fig. 550. Sasanian coin (front and back sides). By delafua

Coins of Arsakids and Sassanids (fig. 550) have the same character with these reliefs, as well as relief images on Sassanian silver vessels, which can not always be distinguished from Bactrian, semi-Indian and Gothic. Undoubtedly, the Sassanian ones must be recognized as some of the silver gban of the Hermitage and the c. Stroganov in St. Petersburg; Undoubtedly, the Sassanian bowls are also, of which the king in the hunt for antelopes and boars is depicted on one in the Paris müntz office, and on the other, in the Hermitage, the king hunting lions; undoubtedly, of Sassanian origin and the golden bowl in the aforementioned Parisian collection with the image of King Khosrov on the throne at the bottom. On it we find luxurious ornamentation of colored stones inserted into gold nests, a method of decoration that we talked about above, as a special trick of European goldsmiths from the times of the resettlement of nations and the Merovingians, probably borrowed from the East.

If the silver bowl collection gr. Stroganov in Rome, depicting a king sitting at a meal with his legs tucked under himself on a carpet laid on the floor and described by A. Rigl, really refers to the Sassanid era, it serves as evidence that the Eastern custom of sitting on carpets on the floor, and not on any furniture, was distributed in the Sassanid kingdom, at least in domestic life. That the Sassanian king is depicted here is more than likely judging by his costume; In addition, the magnificent carpet of later origin, depicting a luxurious garden in strict styling, is in the collection of Dr. A. Figdor in Vienna, consistent with old descriptions of Sasanian carpets, the character of which is reflected in it. Therefore, it must be assumed that floor carpets were in common use, if not yet in ancient Persia, then in Persia of the Sassanid times, and the technique of their manufacture was already assimilated by the then Persians. The essence of this technique is that tufts of wool are attached to the vertical warp threads, and due to the fact that they are overlapped with rows of “weft yarns”, dense fabric is obtained. The carpet depicted on the above-mentioned silver cup collection gr. Stroganov in Rome, even in relation to his pattern, is the predecessor of Persian carpets who later became famous: a wavy line border surrounds the main field, evenly filled with a pattern of stylized plants. Remains of luxurious Sassanian silk fabrics have been preserved in various places; such matter found in the church of sv. Kuniberta, in Cologne, is described by A. Schneutgen and F. Justy. The hunting scene on its middle field represents an episode from the life of Prince Baram Gore (420-434), in the dining room of which, according to written legends, hung a picture on which the pattern of this fabric was woven. In general, Sasanian ornamentation in weaving, as in other branches of art, is a link between the ancient world and Islam.

Fig. 551. Sassanid capital from Isfahan. By delafua

Fig. 552. Capital pilasters from Tage-Bostan. By delafua

Ancient oriental elements are also found in places in the decorations of Sasanian buildings, but usually with the modifications that this kind of ornaments received in the Greco-Roman world. Rigl rightly remarked that the still bushy acanth, plastically reproduced on one Sassanian capital from Isfahan (fig. 551), regardless of the modern ornamental motif of the evolution of Byzantine art, has the character of a true Hellenistic acanthus. Only the middle beam and here seems to be the predecessor of the later Arab-Persian cup-shaped palmettes. Then on the capitals of one pilaster from Tage-Bostan (fig. 552) we observe further development parallel to the Byzantine one. And here the main element is “a vegetable bush with a fleshy trunk, in the form of a candelabra”, but the leaves coming out of the trunk have already lost the character of acanthus, and the flowers, shown alternately visible from the side, now above and hanging, like rosettes, on the tips of the leaves, resemble a stylized vegetative ornamentation of the Arabs.

But the ornamentation in the Hellenistic-Roman spirit, which fills the pediment of one Sassanian palace in Mashite, is very realistic. Here, the vines and animal figures intertwine and form one luxurious whole, but the combination of fairly pure Hellenistic forms with Byzantine stylized indicates that the art of the Sassanians in artistic terms, as in the historical, occupies a middle position between the classical and Arabic arts.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)