When Emperor Constantine, after the victory over Maxentius on the Milvia Bridge, won in 312 under the banner of the Cross, entered Rome, the triumph of Christianity, which had been prepared for a three-century struggle, was already complete. Christian art, too, after the religious tolerance edicts of 313 and 314, rose to an unexpected height.

In all the provinces of the Roman Empire, his victorious march began now: in Alexandria, where, unfortunately, only a few monuments survived, as in all of Egypt and North Africa; in Antioch, the treasures of which are still waiting for excavation, as well as throughout Syria; in the middle countries of Asia Minor covered with the breath of the East, whose monuments were put by Strigovsky in the forefront of the Christian art movement, as well as in the Hellenistic cities of the Asia Minor coast; in Thessaloniki, as in Greece itself; in Rome, which soon lost its world domination, as in other big cities of Italy, to which Ravenna has joined since the 5th century. Great importance for the further development of art, as in general for world history, was the fact that Constantine, shortly after the restoration of autocracy in the empire, turned his back on old Rome, in order to establish a "new Rome" in Byzantium, on the shores of the Thracian Bosphorus, today retains the name "City of Constantine." Ancient Byzantium as a new Rome became the prototype of the Christian city and the focus of Christian artistic activity. There is no doubt that Byzantine art already in the 5th and 6th centuries had its own special appearance, but it is equally certain that the characteristic features of this ancient Byzantine art were pre-formed in Alexandria, Syria, Asia Minor, and to a much greater extent, in features in the Sassanian, East; then it can be assumed that the new art forms of the East Asian and African East, which developed only in this “late antique” era, in many cases penetrated to the West and directly, bypassing Byzantium. The end of this epoch is felt where the ancient basis of art begins to be lost; This border is designated in the West by borrowing northern artistic elements, in Constantinople, which would be opposed by iconoclasm, and in the Hellenistic East by the victory of Islam.

The first great work of Christian architecture was the creation of a church.

The complete opposite of the Greek temple, which was conceived as the dwelling place of the deity, the Christian church, even when it was erected over the grave of the martyr, above all - the house in which believers gather; therefore, whereas in the construction of a Greek temple, attention was paid mainly to its appearance, the ancient Christian church architecture took care mainly of the dismemberment and decoration of the interior. From the very beginning, along with round or polygonal central churches, that is, located symmetrically around the vertical middle axis, we meet oblong churches with a raised middle nave — Christian basilicas that, fully responding to the religious need of believers, were the dominant form during the first centuries after Constantine the Great European temple building.

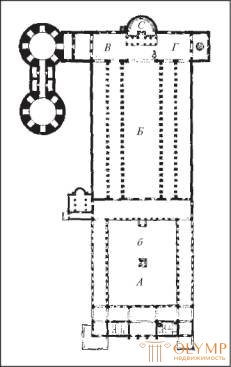

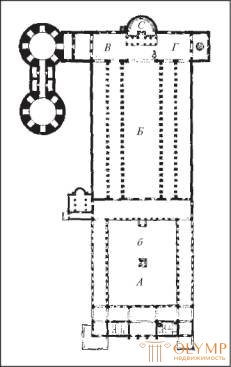

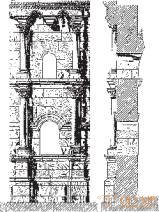

The original plan of the Cathedral of St.. Peter in Rome (Fig. 9) can give an idea of the constituent parts of the western Christian basilica; Internal view of the Cathedral of St.. Paul in Rome, restored after the fire of 1823 (Fig. 10, above), gives a general idea of the interior of the basilica. Although in the East the basilica developed earlier than in Rome, we appeal primarily to the Roman churches of this kind, which are more accessible to us.

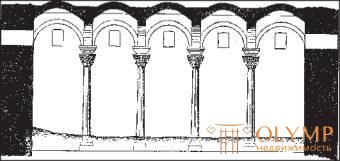

The Christian church was supposed to contain two main rooms - a vast hall for the gathering of believers and, to the side opposite to the entrance to it, an altar space for worship. These parts were joined outside the building — an atrium (porch), and inside — a narthex (porch) intended for the penitent and announced. The quadrangular atrium (see Fig. 9, A) is surrounded by walls, along the inside of which is a colonnade with a sloping roof; in the middle of the atrium there is a well for washing hands (b). The inner porch, which is constantly found in the East, is absent in Roman basils. The main, middle door, in addition to which there are side doors, leads from the atrium to the large rectangular hall for meetings of believers (B). This hall is usually divided in the longitudinal direction by two or four rows of columns (less often pillars) into three (or five) naves. The middle nave is often twice as wide and twice as high as the side aisles. Columns are connected to each other through a direct entablature or arches. Middle rows of columns support the walls in which the windows are made; the single-slope roofs of the aisles rest on these walls with their top; the middle nave is covered with a gable-tiled or shingle roof with flat gables. From the inside, wooden rafters supporting the roof in the Roman-Hellenistic world were either completely open and visible, or covered with a flat ceiling, divided into quadrangular fields, whereas in the East this device quite often replaced the stone vault. But sometimes the upper walls of the middle nave rest on the second row of columns, which open inwards the empores (choirs) of the aisles, which are rarely found in the West (see Fig. 10, below).

Fig. 9. The original plan of the Cathedral of St.. Peter in Rome. By holzinger

Fig. 10. The interior of the early Christian churches near Rome: the church of San Paolo fuori le Mura (above); lower church of sv. Lawrence (below). With photos Alinari

The exterior decoration of the western Christian basilica (usually built of brick) was extremely simple, the decorative elements in it were almost absent. The facade with a triangular pediment expressed a transverse tear of the building. The roof covering meant one expediency. The toothed cornice under the roof, on the walls of the lizen (small protrusions serving to revitalize large planes) often constituted the only external decoration of western basilica. The towers that appear only at the very end of this era, and the baptismal (baptistery), generally of the central type, as a rule, stood apart from the churches. Only in the middle of the century did church architecture change the appearance of the western basilica following the pattern of its Asia Minor and Syrian sisters, whose forms from the very beginning were more developed into a powerful organic whole.

There is no doubt that the ancient Christian basilica owes its origin to the ancient architecture. But then the question arises from which Roman-Hellenistic structures the basilica developed. Can we, along with many old and new researchers, consider it as prototypes of commercial, private basilica, school halls? Or should we agree with the opinion of de Rossi and Kraus that the pagan basilicas and the Christian cemetery chambers merged into the Christian basilica (see fig. 1)? Did Degio and Victor Schulze prove that the churches came directly from the living quarters of an ancient Roman house? A convincing sound is the explanation of Golzinger, who called the creators of the Christian basilica "eclectic", who chose the most expedient from a rich stock of ancient architectural forms and connected them into one harmonious whole. Let us recall at least the plan of the Maxentius basilica (see vol. 1, fig. 506) or the hypostyle hall with a flat ceiling of ancient Egyptian temples, illuminated with windows in the upper walls of its elevated middle nave (see vol. 1, fig. 128); We also recall the tabernacle sanctuary on Samofrakiya Island (see t. 1, fig. 445), in which we find a portico, a three-nave cella, a column-free space in front of a semicircular niche in the back wall, in a word, almost all the constituent parts of the basilica. In the end, the old position of Zithermann, which he put out in 1847 (the Witting came to this position), remains in force: the Christian basilica owes the ancient Roman trading and judicial halls only its name, it itself is a new creation of Christian architects from the needs of the cult. But at the same time, of course, these architects necessarily adhered to traditional forms.

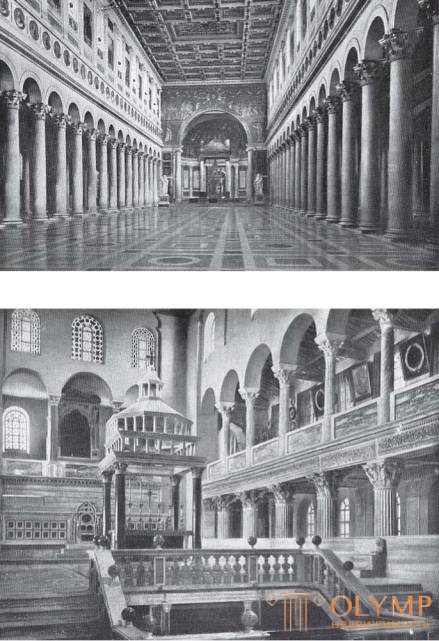

A large, compared with the basilica, the diversity in its architecture was represented by the central churches of this era, which were now round, then four, eight, or decagonal, then cruciform; accordingly, they can be brought into closer contact with pagan specimens, preserved in significant numbers in buildings of Roman palaces, baths, temples, and even wider than in Rome, common in the Hellenistic and Far East. Already the decagon of the so-called temple of Minerva the Doctor in charge (Minerva Medica) in Rome (see vol. 1, Vol. 4, II, 1) serves as a transition to Christian central structures with internal circular galleries. The difference in types of dome cover, from a simple overlay of a round dome on a circular base, to a dome supported by four pillars connected by semicircular arches and connected to a quadrilateral by means of spherical wedges (pandantypes, or sails, see Vol. 1, Fig. 512), characterizes one of the largest stages of architectural evolution.

Vaulted ceilings and a dome covering the middle of the building make up the essential belonging of the central architecture in the West, which used them initially exclusively for baptistery and tombstone and memorial churches, while in the East, the ancient fatherland of the dome, many grandiose church buildings, which later influenced the western art.

Fig. 11. Section and plan of the church of sv. Constantia in Rome. By holzinger

Constantine the Great decorated the new Rome with palaces and temples, on the coast of the blue Bosphorus, even more luxurious than the ancient one. These palaces and temples have long disappeared from the face of the earth, and only from ancient descriptions collected in the writings of V. Unger and J.-P. Richter, we know about the numerous basilicas of Constantinople, among which the first place was occupied by the old temple of Sts. Sophia; only from literary sources do we know the magnificent tomb church of the emperor and the church of sv. Apostles, which at the time of Constantine consisted of four cross-shaped naves; in the quadrilateral formed by their intersection, 12 columns, symbolizing the 12 apostles, supported the gilded dome. But the first Christian emperor decorated the Holy Land with the most luxurious and significant church buildings. A large five-nave basilica with empores over the side aisles stood near the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. The church of the Nativity of Christ (or Theotokos) in Bethlehem, which has survived to our time, also has five naves; at least its longitudinal part is ancient. The most famous central religious buildings of the East belonged to the octagonal church in Antioch, the extensive circular church on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, and the magnificent Church of Nicaea, in which the first Ecumenical Council sat in 325. The above-mentioned Jerusalem Basilica was connected through a two-tier portico to the magnificent Church of the Holy Sepulcher, which had the shape of a rotunda and crowned in the middle, above the Holy Sepulcher, with an open dome at the top. The remnants of this structure, which are part of the later buildings, published Strigovsky. Their rich cornices, with cords of pearls and lush curls of acanthus, resemble the ornamental motifs of Balbec and Palmyra (see vol. 1, fig. 508–510).

It goes without saying that all these magnificent Constantine buildings in Palestine, which embodied mostly Eastern architectural ideas, had a great influence on the further development of Christian church architecture.

A huge number of ancient Christian churches of the post-Constantine period, both in the eastern and western countries of the Mediterranean, reached us partly in ruins, partly in fairly good preservation. A whole series of scientific studies is devoted to the treasures and remnants of this artistic world; for the West, along with the valuable, but demanding while using it some caution by the work of Gübsch, mention should be made, for example, of the publication of Degio and Bezold. Monographs of Texier, Wood, Wolfe, Salzenberg, Quasta, de Vogue, Buttler, Strigovsky and others introduce us to the Christian monuments of Asia Minor, Constantinople, Ravenna, Syria and Egypt.

One of the main centers of early Christianity was Egypt, and the center of ancient Christian scholarship was its capital, Alexandria.

Egyptian Christians, whom the Arabs later called the Copts, were the bearers of the ideas of asceticism. The Nile Valley became the birthplace of the desert and monasteries.

Fig. 12. The wreckage of the cover of the Coptic sarcophagus. According to wrigle

Fig. 13. Plan of the Basilica in Orleansville. By holzinger

From the early Egyptian basilicas, among which the church of St. Mark in Alexandria, nothing is preserved; but of the later Coptic churches, with their remnants covering considerable space, several have come down to us, quite clearly proving the eastern character of this architecture. These are wide and short basilicas, which, according to Butler, often have a dome or half-dome over the altar; according to Gaia, however, they are dominated by a flat coating; their arches - elongated or broken. The Roman transept is absent in them, but there are empores above the side aisles. The main Coptic church in old Cairo is Mari-Girgis, that is, the church of St. George; its apse is with semicircular ledges. One of the oldest monasteries is Anba-Shenoudi (White Monastery), whose three-nave church dates back to the V century.Its gates and stone fence are topped with an ancient Egyptian grooved cornice. In general, the echoes of ancient Egypt in Coptic art are not as rare as it was claimed in the past. True, ornaments of sarcophagus covers, church grids and others appeared on the Hellenistic soil, but here and there (Fig. 12) they already reveal a transition to a geometric stylization of plant motifs so beloved by the East.

Fig. 14. Ornamented plates from the basilica in Tebessa. By wieland

Fig. 15. Part of a series of columns encircling the absid of the church in Kalat Siman. By de vogue

As a prototype of the Syrian churches, you can point to the so-called Mouri Midje pretory. Usually and, apparently, it is correctly attributed to the pre-Constantine time and is considered a work of a pagan architect; but some researchers, such as the Horn. Gurlitt, they see in it a Christian church of the 5th century, which is at least doubtful. A magnificent six-column portico leads into a square hall with four columns in the middle and 12 semi-columns along the walls; these columns are connected by arches. A flat dome rests on the four middle arches. Four cross-shaped wings are covered with camber arches. Against the portico is a semicircular niche, and on both sides of it - two quadrangular chambers. We find the same arrangement of parts in the later Byzantine churches. And this example proves that the central buildings more closely than those elongated in length, are adjacent to antique designs.

The real oblong basilic type churches that prevail in Syria are distinguished by stonework (sometimes, like, for example, in Sciacca, the tree is completely absent in the structure), and accordingly this predominantly “constructive” character. There are neither transepts nor empores in them.

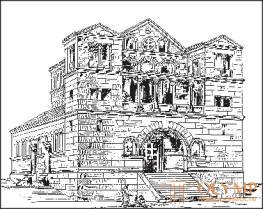

Free-standing columns connected by semicircular arches are in them as a general rule; but in the basilica of Ruwekhi and Kalb-Luza, the columns are replaced by pillars. The usual semicircular apse often does not appear as the outer rectangular outline of the basilica; diaconics and profesis are often joined to it. In some of these Syrian churches, medieval features are anticipated, so to speak: in Kalb-Luz, Turmanin and Kalat-Siman, small columns standing on brackets support the ceiling beams of the upper tier; in Kalb-Luz and Kalat-Siman, the same columns, moreover, encircle the outer wall of the semicircular altar niche (Fig. 15). The facades of the churches of Kalb-Luze and Turmanin are especially luxurious (Fig. 16): the upper portico (loggia) rises above the open narthex; on its sides are two four-sided towers with stairs inside. These towers, though not exceeding the middle of the pediment, are the first belltops known to science, organically connected with the church.

Fig. 16. Church in Tumanin. By de vogue

Greater autonomy is also visible in separate ornamental forms of Syrian basil. In some places, there is already a characteristic frieze of the Romanesque style (a series of arches under the eaves). The capitals of the columns of the middle nave are formed so loosely that they often only resemble the Ionic or Corinthian order from a distance. In the large, precisely swayed by the wind, leaves of the capitals of Kalat-Siman, one can hardly recognize the forms of the acanthus. The curl of the acantha, with strongly shortened stems, with flowers in the form of leaves and wheel-like rosettes on the door cornice of the church in El Barra (Fig. 17), is already on its way to styling in the Byzantine spirit.

Fig. 17. The door cornice of the church in El Bar. By de vogue

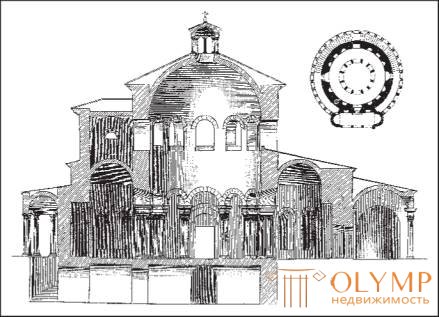

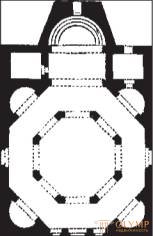

The transition to the central buildings in Syria is the magnificent commemorative church in Kalat Siman, reminiscent of the St. Konstantin Church. Apostles in Constantinople. The four basilica-shaped parts, located to the east, north, west and south, constitute the four wings of the middle quadrilateral space, turning into an octagon, having no covering. The present central temples include the Cathedral in Bosra and the Church of Sv. George in Esra. The Cathedral in Bosra (Fig. 18), as the inscription on it says, was built in 511–512. It is a quadrilateral outside, and a circle inside; the semicircular apses are located at the corners of the quadrangle.

Fig. 18. Plan of the cathedral in Bosra. By de vogue

Church of sv. George in Esra (Fig. 19) has a square in plan, the inner corners of which are occupied by semicircular niches; the middle space here is octagonal, and eight pillars connected to one another by arches support a high dome; the transition from the octagonal base to the dome dome is made up of hexagons, but not yet spherical pandantives (see v. 1, fig. 512), which will soon become part of Byzantine church architecture.

In Hellenistic Asia Minor, Syria and Macedonia, we are returned to a different kind of church, occupying an intermediate position between the basilica and the domed churches with a cruciform plan. In them, the quadrilateral formed by the intersection of aisles — its pilasters still closely joined with the outer walls — is blocked by a dome, while the building’s length is underlined in the plan inserted in front of the apse by a square or semi-square, and in the architecture of the building by the side pilasters or columns and a deeper porch. Whether the overall plan of the building remains central (in this case square) or, like a real domed basil, turns into a rectangular due to the increase from the west side of the short longitudinal nave - the question is not particularly significant. The famous church of the East, Justinian Church of St.. Sophia in Constantinople, to a certain extent, belongs to this type, although it has been completely reworked in this ingenious structure quite independently.

The magnificent “domed basil” of Khoja-Kilisi in Asia Minor, even in ruined form, the dome of which, however, could be a simple tower with a hipped roof, older than St. Constantinople’s temple. Sofia (537). Younger than him, in any case, the dome of the Basilica of Qasr ibn-Vardan in Syria, in its plan approaching the square. The difference in opinions between Strigovsky and Wulf, the two best German experts on Eastern architecture, came down to the fact that it was older or younger than the Church of Sts. Sofia is the most famous of the square churches of this kind, for example, the church of Sts. Nicholas in the World, the Church of St. Clement in Ankira, especially the Church of the Assumption of the Virgin in Nicea and the Church of Sts. Sofia in Thessaloniki. Strigovsky saw in them the predecessors of Hagia Sophia, and Wulf, like most researchers, imitated her, only in a simplified form.

Thessaloniki basilicas, which, like those of Asia Minor, everywhere have semicircular arches instead of direct entabers, empores above the aisles and already developed imposts above the columns, take us to Constantinople. The church called Eski Jami belongs to Thessaloniki in the first half of the 5th century, and by the middle of the same century the church of Sts. Dimitri, in which the pillars alternate with pillars. Church of sv. George is a simple round construction, the half-dome of which directly lies on strong external walls, dissected inside by quadrilateral niches.

Armenia was in close contact with Syria and Asia Minor. Affected by pagan times by Roman-Hellenistic and Sassanian artistic influences, it seems that from an early time it took an active part in the development of church central structures. In 1903, Strigovsky, who previously considered Armenian art to be the successor of Byzantine, expressed a different opinion about him, according to which octagonal structures and cruciform domed churches appeared in Armenia quite independently, and in general, Byzantine art (later) received more from Armenian than it delivered to it. The church of Sv. Gayany in Vagharshapat, built about 600 g .; It is curious that its middle dome was supported by already four free-standing pillars, and the transverse part was covered by a basalt vault. In opened in 1900, the round church of St.. George near Echmiadzin, founded around 650 by Catholicos Narses III, the four middle pillars are interconnected by groups of six columns arranged in a semicircle. These columns belonged to the basket-shaped capitals found by Strigovsky in the garden of the Echmiadzin Theological Academy. The somewhat later Patriarchal church in Echmiadzin, with its square plan, has an elliptical niche in each of the four sides.

Constantinople - the rich palaces of new Rome, spread out on seven hills along the banks of the Bosphorus, the center of Byzantine art; We will first consider two centuries that have elapsed between the death of Constantine and the accession of Justinian to the throne.

In Constantinople there were not so many old buildings for plundering as in Rome, but the abundance of marble in Proconnes (in the Sea of Marmara) was already in the 4th century. allowed the generation of stonecutters to appear. The century Theodosius saw the first steps in the development of a new, Byzantine architecture, retreating from the common Roman-Hellenistic art forms, but nonetheless, as Strigovsky proved, closely related to the Christian art of Western Asia and Egypt. The Golden Gate, built by Theodosius the Great between 388 and 391, is the oldest Byzantine architectural monument of this kind. Simple and massive, these gates made an impression with their monumental side towers, reminiscent of Egyptian pylons (see t. 1, fig. 128), and the strict grandeur of the white marble facade. Pilasters on the sides of their three spans are decorated with Corinthian capitals; For the first time in Europe, on the leaves of acantha, one can see a deep cut of the blades, characteristic of Byzantine art (perhaps, transferred from Egypt), which here was the first step to geometric styling. Further development of the Byzantine style we already see in the Outer Gate, built half a century later. On both sides of their span are columns; the facade is decorated in two tiers with false columns and entablments: the rectangular fields formed by these latter were filled with reliefs on scenes from Greek mythology. Capitals of columns - a type of capitals of the composite style, with erect leaves, instead of ionics (s), between volutes; their feature is made by plastic images of birds playing the role of angular volutes. In contrast to the harsh simplicity of the Internal (Golden) Gate, these multi-colored marble sawn cuts already reflect the increasing pomp of the Byzantine courtyard.

Fig. 20. Underground reservoir Eshrefidzhe-Sokagi in Constantinople. According to Strigovsky

The parallel development of architectural forms can be traced through the underground public reservoirs of Constantinople (Bodrum). These are extensive, dimly lit galleries, the arches of which are supported by columns. In Alexandria, famous buildings of this kind are known, in several tiers one above the other, with columns of white marble and red syenite; Alexandrian architects built and Constantinople Bodrum era of Theodosius II. The oldest Bodrum that have come down to us (built, in all likelihood, around 421) - Eshrefidzhe-Sokagi (Fig. 20) and Chukur-Bostan. In the first, the vaulted ceiling rests on 28, in the second, on 32 columns of the Corinthian, but with elements of the Byzantine order; in both between the capital and the fifth arch, the above-mentioned impost is inserted - a cube with a trapezoidal face, which is beveled down, replacing the entablature protrusion. Contrary to the views of Portheim, Ryvoira and others, we remain convinced that the impost appeared here earlier than anywhere else in the West, even earlier than in Ravenna.

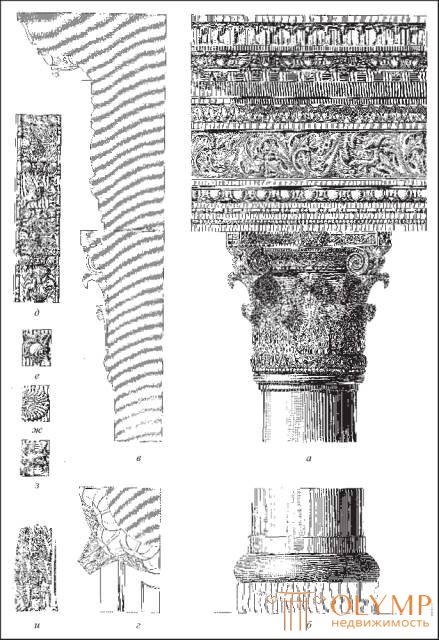

Fig. 21. Column and entablature of the church of sv. John in Constantinople: a and b - front view; in - the profile of the capital and entablature; g - bottom view; d - leaf foliage capitals; e, f, s, and - bottom view and details of the cornice. According to Salzenberg

Fig. 22. Tank Bin-Bir-Direk in Constantinople. With photos of Seb and Joailier

The century of Theodosius (V) is followed in Constantinople by the century of Justinian (VI). If, referring to the architectural monuments of this century, we look first into the underworld of reservoirs, then arouse the greatest interest

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)