While the ancient Christian architecture invented rooms for prayer meetings of believers that were beautiful and worthy of this purpose, the task of painting in the era we were considering was to give the religious concepts of Christianity, freed from oppression of persecution, an artistic expression corresponding to the importance of the subject. If now, as before, we have to talk about rather mediocre, nameless works of this branch of art, again becoming a branch of the craft and with each decade losing understanding of forms, then, on the other hand, it should be noted that its content was often formed under the direct influence of richly gifted people, advanced minds of the time, pastors, prophets and singers of the new religion, and no matter how far the form and content of this art were from complete fusion, yet in many cases, especially in mosaic images It is very interesting to see how conscientious, colorful and decoratively effective craft painting itself is becoming more and more spiritual and significant in its reflection of high feelings in itself.

Wall paintings of this era can be best studied in the catacombs. Christian frescoes IV – VII centuries. Neapolitan and Sicilian underground cemeteries are rich, the study of which involves the names of the Fuhrer and Victor Schulze. Separate Christian grave murals were discovered in Alexandria and Fünfkirchen, but the Roman catacombs still provide the most complete picture of the development of Christian wall painting. True, from the beginning of the V century. they no longer buried the dead in them; but it was from that time that the graves of the martyrs became a place of reverent worship; Pope IV – VII centuries. the crypts of the martyrs were repeatedly restored and their walls were decorated with new paintings, and only from the time of the Lombard invasions did access to the catacombs cease.

Connected rows of biblical scenes, which after the world of the Church we observe in large church paintings and miniature paintings, are still not found in the cubicles of the Roman catacombs, and in the 4th and 5th centuries. Only a small number of new images, borrowed, of course, from the East, can be installed along with the old ones. Of the symbols are new, for example, two deer drinking water flowing from a rock, in the fresco of the catacomb of Domitilla, or the Lamb of God on a hill from which four heavenly rivers (the four Gospels) flow down, in the cubicle of St. Peter and Marcellinus. From the biblical scenes in a new way presented Christmas, in the catacombs of St. Sevastian (Baby, in swaddling clothes, with a radiance around his head, lies in a manger, near which an ox and a donkey stand), and an image of the Savior among wise and foolish virgins, in the catacomb of St. Kyriaca. The crucifixion appears in the catacombs only a few centuries later, for the first time - in the catacomb of St. Valentine, on the fresco, which Kraus attributed to the VII century, and Marukki - to the VIII. On the Crucified - long clothes, the saints are standing at the cross; the legs of the figures are not preserved. Thick black outlines and sketchiness in the poses of the figures also indicate here an era that has broken its connection with the old pictorial tradition. Christ and the saints more often appear now in the plots of catacomb painting in their true meaning. In the charming fresco of the catacomb of Domitilla, depicting the young Christ on the throne and on the sides of His four saints, according to Kraus, the four evangelists, we have a prototype of all the latest "holy conversations."

It is characteristic that here, in the middle of the 4th century, Christ was still without a beard, but with a simple radiance (nimbus) around the head, which, according to Crow, Cavalcazelle and Kraus, can be considered the most ancient nimbus in catacomb painting. We meet Christ with a beard for the first time in catacomb painting on the above-mentioned fresco with wise and unwise virgins. Christ among the disciples is now depicted more and more often with a beard and a halo. But the actual portrait of a young bearded Christ with a round shine around the head appears relatively late. A half-length image of this kind (more than in nature) in the catacomb of San Grandioso (S. Grandioso della Vanita) in Naples dates back to the sixth century, and the older of two similar heads, in the catacomb of St. Ponziana in Rome (Fig. 35), to VII. On both sides of a regular, framed face with a small beard, long hair, separated in the middle, falls; some sketchiness is already noticeable in the arched eyebrows; round shine around the head is decorated with a cross; in general, it is the ideal, meek type of Savior, later assimilated by the Renaissance. On the other hand, the transition to an old, harsh type of Christ, usually considered Byzantine, is visible, for example, in the belt image located in the crypt of St. Cecilia in the catacombs of Callixt (Fig. 36) and written, probably, in the VIII century.

Fig. 35. Head of Christ. Fresco in the catacomb of sv. Ponziana in Rome. By Perret

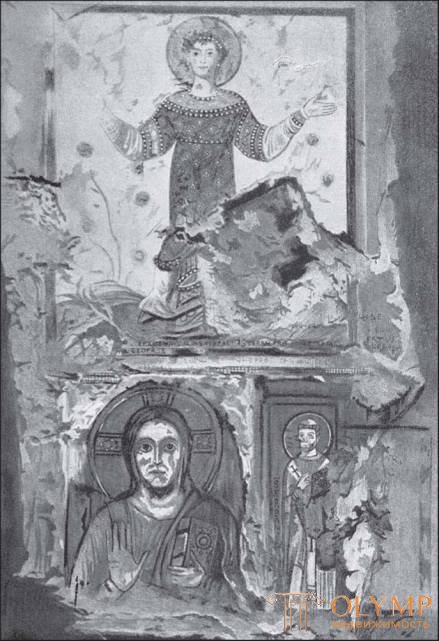

Fig. 36. Fresco in the crypt of sv. Cecilia in Rome. By de Rossi

Fig. 37. Oranta. Fresco in the house at the church of sv. John and Paul in Rome. By germano

A new, noble art world opens before us even during the life of Constantine the Great in the paintings that adorn the interior of basil and round churches. They were performed in part by mosaic, part by brush with al fresco. Among the literary sources, from which, after the research of Julius von Schlosser, Steinman and Vikgoff, we draw information about the ancient church painting, the first place is occupied by the preserved signatures under the sacred images (tituli), usually composed in verses. The 24 titles attributed to an equal doctor and deacon Elpidia Roustik (died in 533) clearly show that in the series of biblical scenes there was a parallelism between the events of the Old Testament and the New Testament: thus, the Fall was compared with the Annunciation, The Sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham - with the Crucifix. The composition of the symbolic mosaic in the apse of the basilica of sv. Felix in Nola could be restored by Vikgoff with the help of verses of St. Peacock (353–415), biblical wall murals in the dining room of the Equal Bishop of Neon (about 450) according to the description of Aniella (839). The sources even talk about the paintings of the church of St.. Martina on Tour, in Merowing Gaul, and the Church of the Abbot Benedict of Wyrmaus and Jarrau, on the other side of the English Channel (678-684).

But, of course, even more attention than all these testimonies deserve the remaining church frescoes and mosaics of the time in question. Among the few extant frescoes, the painting of the church of Sts. Maria Ancient (S. Maria Antiqua), open to the Roman Forum. Here we have a whole museum of early medieval painting. Christian antiquity is represented by the Crucifixion of the VIII century. The Savior is depicted still alive, with open eyes, in long clothes, with legs separately nailed to the cross - the composition features that remained typical until the late Middle Ages. Of the figures standing at the foot of the cross, Mary, John and Longin are inscribed. The contours are only slightly circled, and the plot is interpreted still relatively picturesquely.

Church mosaics, as opposed to frescoes, have come down to us in significant numbers due to the greater strength of their equipment; they convince us that the decoration of churches through these paintings, made of colored glass cubes, shining bright, thick colors, paintings that created a new vast area of sacred images, was a real artistic feat of Christian antiquity. For acquaintance with Roman mosaics, along with the publication of de Rossi “Musaici e saggi dei pavimenti”, the works of Müntz and Gershpach are of particular importance for us, and for Equal mosaics - the works of Jean-Paul Richter and EK Redin.

Fig. 38. The killing of three martyrs. Fresco in the house at the church of sv. John and Paul in Rome. By germano

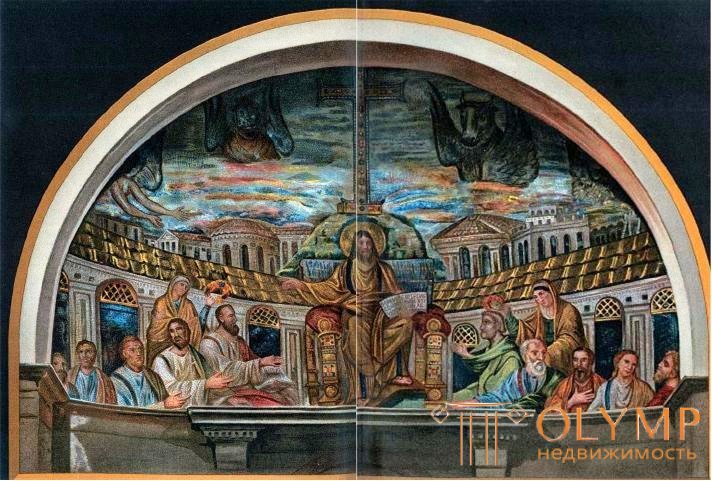

Fig. 39. Mosaic in the apse of the church of sv. Pudenziany in Rome. With a copy of K. Otto

Only the vaulted parts of the churches and the upper walls of their longitudinal hull were covered with mosaic paintings. The bottom of the side walls was covered with carpets with images woven on them, but more often they were decorated with patterns of multicolored marbles (opus sectile), which served as a good connection between the upper glass mosaics and more roughly ornamented (rhombuses, circles, crosses, ribbon weaving) stone floor. At the top of the longitudinal walls of the middle nave, the events of the Sacred History were mainly reproduced, now located in a sequence of separate scenes. In the apse and on the triumphal arch, the apocalyptic heavenly glory was depicted, the victory of the Church, the triumph of the Savior, or those saints were glorified, whose memory is dedicated to the church. Everything that was read or preached from the pulpit seemed to the eyes of the congregation alive, visual images.

By the IV century, finally, a magnificent mosaic of St. Capella. Rufins and Seconds in the Lateran Baptistery (Portico di San Venanzio). In the middle of the abscess is a lamb, and on its edge are pigeons; on the dark blue background, golden-green curls of the acanth with a flower inside each curl stand out spectacularly. The dark blue background from this pore completely displaces white from the mosaic until it, in turn, displaces the golden one.

Then you should point out the wonderful mosaic decorations of the church of Sts. Mary the Great (S. Maria Maggiore). Biblical compositions at the top of the walls of the middle nave, some scholars refer to the time of Pope Liberia (352–366), at which the church was built, while others, with great reason, by the time of Sixt III (432–440); the mosaic of the triumphal arch belongs to the same epoch, whereas the apse mosaic is a work of the late Middle Ages. In any case, in forty scenes from the books of Genesis and Joshua, adorning the middle nave, we have for the first time a rather long series of biblical images, although only Old Testament. True, the ancients of these 40 mosaics can only be recognized as 27. Landscape elements are often obscured by the arrangement of events in two planes, one above the other, and more often, the introduction of a golden background in places. In these mosaics, despite the fact that the technique of individual figures is already barbaric, each composition as a whole is natural and understandable. The small size of these paintings suggests that they were not composed for church decoration, but rather for miniatures. Both sides of the triumphal arch are decorated with three parallel rows of New Testament scenes relating to the dogma of the virginity of Our Lady. In the top row, for example, on one side, the broad scene of the Annunciation, in which the Ever-Virgin Mary is depicted sitting and spinning purple, also corresponds to the widely composed scene of the Presentation of the Lord, on the other side.

In the 5th century, a mosaic was made on the inside of the portal of the church of Sts. Sabina, where on a gold background are depicted, as evidenced by the inscriptions, “the church of the circumcision” and “the church of the pagans”, and the mosaic (heavily restored) on the triumphal arch in the church of Sts. Paul outside the walls. In the middle of the second of these mosaics is a belt image of Christ, of a strict type; 24 apocalyptic old men in white robes approach him from both sides, holding crowns of glory in their hands. In both churches, the gold background in different places of the images alternates with blue.

Absid mosaic of the church of sv. Cosmas and Damian (S. Cosma e Damiano) proves that in the first half of the 6th century, mosaic art still stood at a considerable height in Rome. In the lower lane on a golden background, among a green meadow, on a hill from which flow four heavenly rivers, stands the Lamb, surrounded by apostolic lambs. The background of the main composition is dark blue. In the middle, in rainbow clouds, a giant figure of Christ, with a stern face framed with a small beard, hovers. Below, on the ground, the apostles Peter and Paul lead Christ to the Cosmos and Damian, handing them over to the Savior. In the corners, under palm trees, there are the founders of the church: on the left - Pope Felix III (image restored), on the right - St. Theodore In the figures of this widely conceived monumental mosaic, despite the rich, purely antique draperies of the apostles, there is already some rigidity; nevertheless, from the point of view of content, this composition, with the image of the Savior twice repeated as it is described in the “visions,” represented a new stage in the development of Christian iconography, as indicated by its surprise and imitation. On the mosaic of the triumphal arch of the church of Sts. Lawrence outside the walls (S. Lorenzo fuori le mura) The Savior is depicted already on an even golden background, with gloomy facial features sitting on the globe; the same gold backgrounds have motionless, as if numbed mosaic figures of the church of Sts. Agnes outside the walls (between 625 and 638), - mosaics, in the composition of which the saint for the first time occupies a central place, as well as mosaic figures of the round church of Sts. Stephen (S. Stefano rotondo, 642–649), where the cross of Calvary shines in the middle, still without a Savior. The composition of the mosaic of the church of St.. Cosmas and Damian repeated, dry and lifeless, at the beginning of the 9th century. in the church of sv. Praksedy and a little later - in the church of St.. Cecilia. The figures of the saints become elongated, skinny and devoid of any expression; the place of the hatching here is taken by the black outline. The most barbaric of Roman mosaics is the mosaic of the church of Sts. Mark (827–844): the six saints standing on the sides of Christ barely resemble living people; connection of elements, giving the internal unity of the figures of the mosaic of St. Pudenziany, is completely absent here; figures stand, like statues, apart, on separate elevations. It should not, however, be forgotten that these regressive forms were harbingers of moving forward on a new basis.

V century, belong in Ravenna, above all, the famous mosaics of the ancient baptismal San Giovanni in Fonte. The mosaics of the dome and its pandantes, together with the stucco decorations of the walls, form one luxurious whole. On the middle medallion of the dome is depicted on a golden background the Baptism of the Lord. Christ, already with the features of an elderly man, bearded, stands in the river on the loins; through the transparent waves of the river, the lower part of his body shines through. Opposite John the Baptist, a half-figure of the god of the Jordan River rises from the water, resembling ancient avatars. The next dome belt has another blue background. Twelve gold schematized plants stretch, like the spokes of a wheel, from the lower zone of the dome, decorated with apocalyptic symbols, to the middle medallion; in the intervals between them, 12 apostles, dressed in windblown clothes, carry their crowns on their cloaked hands.

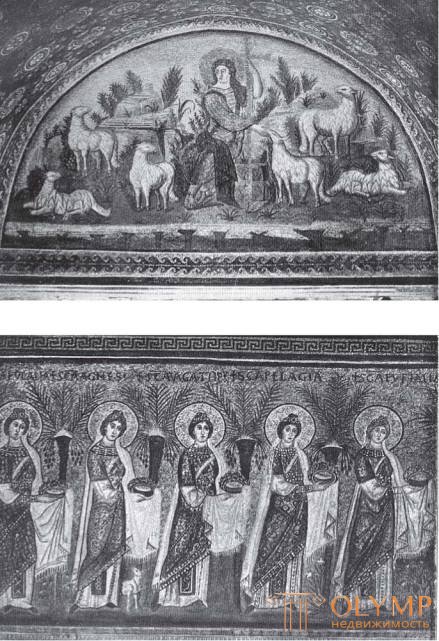

Mosaic decorations of the ceiling and the upper part of the walls of the Galla Placidia mausoleum belong to the 5th century. In the main composition, in the lunet above the entrance door, Christ, in the form of the Good Shepherd, sits among the lambs in a rocky area overgrown with shrubs (Fig. 40, above). Sky is blue; Christ, depicted here as a shepherd and at the same time as a ruler, has a purple robe over his golden garment. In the entire Roman mosaic painting it is impossible to find another image so noble and majestic.

In the 6th century, the mosaic art of Ravenna quickly assumed a different character. The composition of the Epiphany in the Arian Baptistery (S. Maria in Cosmedin) represents only the unfortunate version of the domed mosaic in the church of San Giovanni in Fonte. And mosaics in three rows adorn the walls of the middle nave of the basilica of St.. Apollinaria New, remarkable in its magnificence, and the novelty of the plots. Sketches of this painting were made under Theodoric, and then both the upper rows of paintings were executed; the bottom row is completed only under Bishop Agnell (553–561), who converted this church to a Catholic one. The upper row contains 26 New Testament scenes, 13 on each side, which stretch along the nave under the ceiling itself. Gospel miracles are depicted on the north side (to the left of the entrance); Christ is still young and beardless in them. On the south side, for the first time in Christian art, we meet a series of scenes depicting the Passion of the Lord; The Savior is represented by a hard-lipped, blond, bearded. But the main episodes of the Passion, The wedding of thorns, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, are still missing. This cycle of images ends with the Myrrh-Bearing Wives at the Holy Sepulcher, the Journey to Emmaus and the Appearance of the Risen Christ to the eleven apostles. All these evangelical scenes, whose Byzantine style is proven by Redin on many details, are depicted on a gold background. Individual figures are more sketchy than in the church of sv. Mary the Great is in Rome, but their postures are generally calmer, clearer and simpler. In the middle row, in the piers between the windows, images of prophets and saints are placed larger than in nature. The lower friezes above the column arches, in spite of everything that was not said in their favor by art historians, constitute the main essence of the general impression produced by the painting of this church. On the north side - 22 holy wives, in white robes, separated from one another by palm trees (see fig. 40, below), march from the Klassis gate to the Dormitory of Mary, sitting in the eastern end of the frieze on the throne in a fixed pose, en face, holding The baby is on its knees and surrounded by four angels in the form of winged youths. On the south side, holy men, also in white robes and separated by palm trees, walk from the gates of Ravenna to the Savior, seated against Our Lady, with a strict appearance. Individual figures are already somewhat monotonous and deprived of expression, but their solemn processions, standing out against a golden background, make an indelible artistic impression. In them, so to speak, heard the distant, last echo of the processions of the Parthenon Frieze.

Fig. 40. Ravenna mosaics: Good Shepherd, in the tomb of Galla Placidia (above); procession of holy women in the church of st. Apollinaria New, on the north wall (below). From photos of Alinari

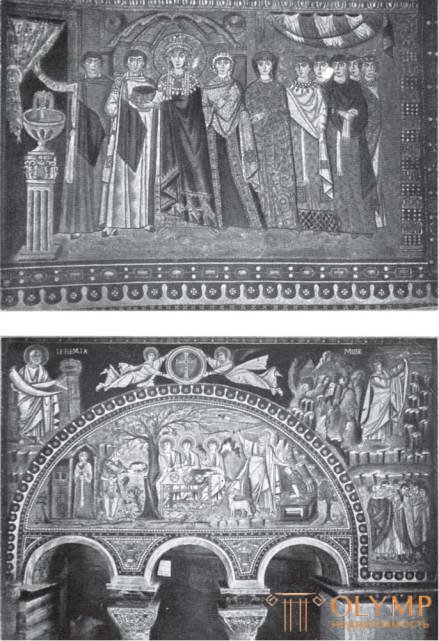

In the middle of the VI. On the walls of the churches of the Equal churches appear images of the Byzantine imperial couple, Justinian and Theodora. Mosaics of the church of sv. Vitali, illustrating, as Kvitt and Schenkle proved, the dogma of the two natures of Jesus Christ and executed, undoubtedly, at the request of Justinian himself, belong to the most important works of ancient Christian painting. In the middle of the main apse, on a golden background, the Savior, still young and bezborody, sits on the globe. Below are two purely Byzantine ceremonial compositions: Justinian is on one side and Theodore (fig. 41, above) with their retinues on the other side: the emperor’s repulsive face, with cheeks with flabby, hairless cheeks, arched eyebrows, a thin nose and squeamishly compressed lips, gives the impression of a real portrait. In the quadrangular space in front of the apse - two paired paintings: on the left (see Fig. 41, below) is Abraham, who serves three angels, and Isaac's Sacrifice: on the right is Abel's bloody sacrifice and the bloodless Melchisedec sacrifice. Between the ribs of the cross vault, with which the chorus is blocked, four winged angels in long robes (Fig. 42) are supported by a floral wreath placed at the top of the vault with the Lamb of God inside. Blue and gold backgrounds alternate in these fields, but in the general impression of the choir's painting the golden background prevails, on which the green color of the landscape of both side paintings stands out most effectively. Mosaics of the Archbishop's Chapel in Ravenna only partly belong to the time in question, and in the church of Sts. Apollinaria in Classe is only a symbolic mosaic of the apse.

Fig. 42. Mosaic decoration of the ceiling of a quadrangular space in front of the apse in the church of St.. Vitali in Ravenna. From the photo of Ricci

Along with the monumental mosaic, since the times of Constantine the Great, miniature painting became more and more important. The long book scrolls of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans are only rarely found in Christian book art, and flipping books, being more convenient for use, are soon made solely usable. The most luxurious of them are written in gold or silver letters on purple parchment. The artists who painted the books were called minitors, from minia (minium or native cinnabar), which they often used; hence the drawings were later called thumbnails. Illuminated with glue paints with a brush. The organic connection between the text and the illustrations is unknown to this early period, as well as the decoration of the initials. Illustrations were usually placed at the beginning of the book and then filled out a whole page, as well as under the text - and then occupied half a page. Along with few secular manuscripts, a significant number of Christian illustrated manuscripts have come down to us, but the complete Bible, decorated with miniatures, has not been found. Most often illustrated are the Pentateuch of Moses, the Book of Joshua, the Psalter, and the Gospel.

Since Anton Springer wrote his article about the miniatures early Middle Ages and provided a foreword great essay Kondakov on Byzantine illustrated manuscripts, research in the field of miniature painting thanks to the work Tikkanen, Victor Schulze, Vikgoffa, Yanicheka, Goldschmidt, Stettiner, Strigovskogo, Dietz, Ludtke and Gazeloff has led to many new and valuable results, and in the history of illustrated manuscripts, the independent meaning that the main eastern cities of xp stianskogo the world, along with Rome and Byzantium, and even to Rome and Byzantium.

Illustrated manuscripts IV. Reached us mainly in copies of a later time. In fact, it seems that only the sheets of the early Latin translation of the Bible (the Italic manuscript), which were kept in Quedlinburg and later in the Berlin Royal Library, belong to the IV century. Their images are also closely related to the miniatures of the Vagican list of Virgil (see vol. 1, Vol. 4, II, 2). Four pages depict 14 plots from the Books of the Prophet Samuel and the First Book of Kings, with still classical forms, but motionless and impassive figures against the blue sky. They are modeled by glare and gold marking.

Most of the early manuscripts illustrated are written in Greek. Of these, the most ancient is the Book of Genesis of the Vienna Court Library. It was probably made in the 5th century, in Front Asia, perhaps in Antioch. 48 miniatures occupy the lower half of the pages, written in silver letters on a purple background. These drawings depict the events of the initial Jewish history, from the fall of Adam and Eve to the burial of Jacob. Separate figures in the same composition are repeated several times at different points in the action. In this case, you can distinguish the work of at least two artists. The first two or three figure-rich miniatures have a purple background of parchment instead of a background and are mostly located in two more or less interconnected rows, one above the other; the rest are landscape background and blue sky. In the former, drawing prevails, in the latter, painting. Of the first, it is worth noting the meeting of Eleazar with Rebekah, among the latter - the feast of Pharaoh and the scene of Joseph’s adoption of his brothers (Fig. 43; in the background they slaughter goats).

Fig. 43. Joseph accepts his brothers. Miniature from the Book of Genesis of the Court Library in Vienna. According to vikgoff

Both there and here the plots are interpreted easily, fluently and vividly, and the Syrian or Asia Minor fauna is depicted with special love and idyllic breadth.

The truth is already close to the Vienna Book of Genesis, written as early as the 6th century, the purple Gospel code stored in the cathedral of the city of Rossano (in Calabria). Ten of his fifteen miniatures (all in a whole page) present in their lower half busty images of prophets, at the top - New Testament scenes, of which, for example, the Last Supper was composed in the same way as the Last Supper in the Equal Church of Sts. Apollinaria New. In contrast, the entire sheet is occupied, for example, by the extensive composition “Christ before Pilate”. The landscape here is completely absent; figures and faces, somewhat steeply turned in profile, are more schematic in drawing than in the Viennese Book of Genesis; the coloring is too bright, the contours are outlined more sharply.

The Rossan manuscript is very similar to the purple manuscript published by G. Omon, fragments of which found in Sinop are kept in the Paris National Library. The miniatures of this manuscript illustrating the Gospel of Matthew occupy only the bottom half of the sheets, and the images of the prophets are not placed under the compositions on the Gospel themes, but next to them. There are not only a landscape background, but also a strip of land under the feet of the figures. Спаситель является на пурпурном фоне пергамента бородатым, в золотом одеянии, с золотым нимбом.

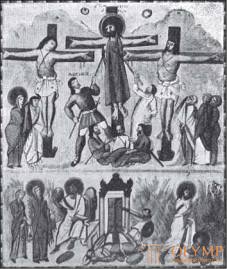

Fig. 44. Распятие и Воскресение Спасителя. Миниатюра Лаврентьевского кодекса во Флоренции. По Лабарту

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)