In contrast to painting, the sculpture, with its large, monumental, warmed by life, high-fiction works, gained access to the church not immediately after the victory of Christianity. Ancient Christian sculpture has not created anything that would be equal, with respect to dignity, with mosaics. But in many respects, the reliefs of sarcophagi correspond to the catacomb frescoes, and the miniatures are small ivory-cut reliefs. Thus, the ancient Christian sculpture was mostly made up of products of applied art; they could be easily moved from one point to another, and therefore the place of their discovery does not always indicate their origin, and since, due to the rule of the Turks hostile to all sorts of images, only insignificant fragments from the sculptures of the once Hellenistic East remained difficult determining the homeland of the works brought to the West, revealing signs characterizing the art of the main centers of the Christian East. All that we now guess about in this regard is due to the research of Bayeux, Shulfaut, Greven and Strigovsky.

Portraits dominated in the round sculpture of this time, as well as the statues of the Good Shepherd. About the bronze equestrian statue of Theodoric the Great in Ravenna, we know only from a written tradition. The majestic, Byzantinely strict bronze statue of the emperor, painted on the market square of the city of Barletta in Lower Italy, is considered to be an image of Theodosius, but it is more correct to see in it the figure of Heraclius (610–641). The most famous statue of the saint of the epoch we were considering was the bronze statue of the Apostle Peter in Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, until Vikgoff proved that it should be attributed, at the earliest, to the XII century. Despite the strong objections of Venturi and others, we continue to share the opinion of Vikgoff; the late Middle Ages are already indicated by the inner liveliness of this statue with its external immobility; In addition, hair curls and beards so schematized are not yet found in ancient Christian plastics. The statues of the Good Shepherd get a slightly different look in this era (see Fig. 7): the young man holds in his right hand all four legs of a lamb lying on his back; in his left hand is a shepherd's staff. Better than others, a preserved specimen of such figurines, more coarse in comparison with the pre-Constantine ones, is in the Lateran Museum. The other two belong to the Constantinople Museum, one to the Athens National Museum and one to the museum in Sparta. Already the sites of the finds of these sculptures testify to their Hellenistic origin.

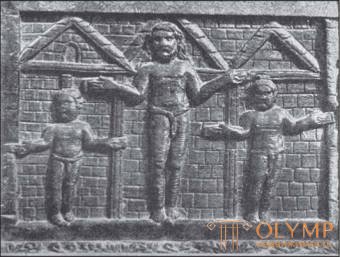

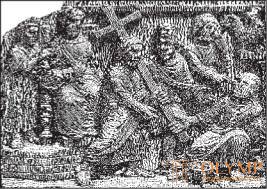

Fig. 48. Crucifixion. Carved of wood relief on the doors of the church of St.. Sabine in Rome. According to Strigovsky

In the area of ancient Christian relief plastics from a variety of mediocre reliefs on sarcophagi and carved bone images, first of all, some works of a special nature are curious. As far back as the 4th century, a rectangular, now disassembled, ivory box in the Christian Museum of Gaps, recognized as a reliquary (lipan), belongs to the fourth century. In his reliefs, distinguished by their skillful separation of fields, calm clarity of composition and confident cleanliness of forms, the most important events of the Old Testament and the New Testament are compared together. This elegant little thing is undoubtedly of Greek-eastern, probably Asia Minor, origin.

At the turn of the IV and V centuries. are re-opened to science Hell. Goldschmidt wooden doors of the portal of the Church of St.. Ambrose in Milan. The main panels of both halves are filled with embossed images from the history of David, but they are so damaged and restored that only two panels stored in the archives of this church can still be considered authentic. Their homeland can hardly be determined.

The preserved famous wooden doors of the portal of the Church of Sts. Sabines in Rome, carved in the V century, are very important for the history of art. Their sashes were decorated with 28 well-placed relief, luxuriously framed panels, of which 10 small and 8 large survived. 5 panels contain images of New Testament scenes, 13 represent Old Testament scenes. The first to the left board of the upper row shows the Crucifixion (Fig. 48). Three crosses, marked only by the ends of the transverse boards, stand in a row in front of the gables of the city. The Savior is almost twice as many thieves. All three figures are nude, and only their loins are covered with small draperies.

The feet of their feet are set apart. The forms here are so crude and lifeless, as if art, having entered a new sacrament at its door, returned to its infancy. But other scenes, such as the taking of the prophet Elijah to heaven, or the Ascension of the Lord, are performed better, more alive, and placed in a richer landscape setting; even more spiritual and at the same time more plastic are such compositions as, for example, the solemn apotheosis of the Church. Three different carvers undoubtedly worked on these doors; Was there at least one Roman among them? Strigovsky argued thoroughly in favor of the Asia Minor or Syrian origin of all these reliefs.

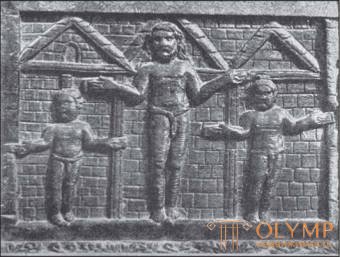

Fig. 49. The front column of the ciborium in the cathedral of Sts. Mark in Venice. With photos Naya

The following should indicate the marble ambon from Thessaloniki - works, the most important parts of which are in the Museum of Constantinople. Here, in separate figures placed in niches, the arrival and worship of the Magi are depicted. In the middle sits the Virgin and Child in the bosom. This is a Greek, fresh, albeit austere work of the Vth century.

A real masterpiece of ancient Christian sculpture is the ivory seat of carved plates of ivory in the Cathedral of Ravenna, presented by Emperor Otton III. According to Venturi, it was made in the 5th century. in Constantinople, according to Greven - somewhat later in Alexandria, according to Strigovsky - in Antioch, but, in any case, in the Christian East. Of the figures that fill in between the twisted columns of the niche of the front side of the seat, the most remarkable is the middle figure of John the Baptist. From the side reliefs should be noted episodes from the history of Joseph; Egyptians, with their wigs, differ sharply in type from Israeli shepherds; camels are depicted from life.

Among the kicking works of ancient Christian plastics also belong to the two anterior alabaster columns of the ciborium (canopy over the altar) of the cathedral of St. Mark in Venice. By definition, Gabelets, they belong to the beginning of VI. and Eastern - probably Syrian - art. Perhaps, they were taken out by the Venetians in 1247, among other columns, from the church in Paul. Each column (Fig. 49) is encircled with nine relief belts, each belt being divided by nine semicircular arches on columns into niches in which images of scenes borrowed from the New Testament and the apocryphal gospels are placed, made in high relief in a luxurious style. The two rear columns of the ciborium are the later imitations of the front.

Finally, the above-mentioned sculptures must be counted, as Strigovsky proved, six curved, ivory-carved reliefs of the pulpit in Aachen Cathedral. They depict the "Coptic saint on horseback," probably of the emperor Constantine, as a champion of the holy faith, a standing warrior, Isis, a Nereid, and two Bacchus figures; a mixture of pagan and Christian motifs, as well as the wild forms of these reliefs, are clear signs of their belonging to the Hellenistic-Egyptian, already semi-Coptic style of the 7th century.

Then there are very curious plastic works of stone and wood (we will return to artistic and industrial ivory products later), which, especially after Strigovsky’s research, can be considered as guiding monuments to study local Christian art in various circles of the Greek East, as well as more distant Christian countries.

At the head of the Egyptian circle sculptures should be put relating, as you might think, even in the IV. Hellenistic-Christian wooden carved relief of the Berlin Museum, depicting the expulsion of barbarians from a religious festival. The brisk, moving figures of the warriors of this relief can be compared to the fighting horsemen on the huge porphyry sarcophagus of the Vatican Museum in Rome, taken for the tomb of Constantine's mother. Fragments of such sarcophagi were found not only in Constantinople, but also in Alexandria. From Egypt and the porphyry itself. Therefore, we must assume that not only the sarcophagus of Constantine's mother, but also his pandanus in the Vatican - decorated with curls of vines and winged babies-geniuses collecting grapes, the famous porphyry sarcophagus in which her daughter was buried, was made in Alexandria. In the 6th century, the wooden reliefs of El Mu-Allak Church in Old Cairo, depicting the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem and the Ascension, were carved out of life. The Savior is represented, as in Byzantine art, sitting on a donkey not as a man, but as a woman. Then the 7th century Coptic art belongs to the Egyptian tomb relief depicting an orant, in the collection of Golenishchev in St. Petersburg. But most of the works of Coptic stone sculpture, collected mainly in the Museum of Giza, are not so interesting in artistic terms that it was worthwhile to dwell on them.

The Egyptian artistic circle is the closest to the Syrian-Palestinian, on the main monuments of which, for example, on the columns of the ciborium of the church of St. Mark in Venice, already indicated by us above.

Another important artistic province of that time was Asia Minor. At the head of the Asia Minor circle, we, together with Strigovsky, put a beautiful marble relief of the Berlin Museum with images of Christ and the Apostles almost life-size. The nobility of the forms, which distinguishes the figure of the young Savior, makes it necessary to attribute this, unfortunately a little weathered, work to the IV century, despite the presence of a halo with a cross, appearing in the East earlier than in the West. Christ, in the posture of the ancient orator, stands between two apostles in a niche crowned with a pediment; as if minted, drilled columns and the entablature of this niche, plastic monuments with similar architectural forms found in the West can also be brought into connection with Asia Minor.

In Constantinople, which depended on Asia Minor, relief-rich reliefs were preserved on four sides of a pedestal of the Egyptian obelisk erected by Theodosius in 390, depicting figures in fixed poses during the ceremony, and fragments of spiral reliefs from the Arcadia column of historical content. But two columns entwined with the vine-shaped drum in the Museum of Constantinople, with very vital images of animals and already somewhat sketchy human figures, for example, in “Baptism”, are especially curious. In contrast to the Syrian-Egyptian circle, Asia Minor and Constantinople form a circle, which for the first time can be called Byzantine; to this circle in the era that occupies us, old Greece must be counted.

In the West, as the main monuments of ancient Christian plastics, one should first of all mention the sarcophagi that have been preserved in large numbers. Taking care of their artistry, Christians, as before and pagans, tried to decorate and consecrate the last close shelters of their dear departed, and although artistic sarcophagi were sometimes ordered in foreign lands, most were made in the places where they were used.

Rome is extremely rich in ancient Christian marble tombs, the front sides of which, as Freedom proved, bear traces of the once-painted on them or gilding. The main side of the Roman sarcophagi, as a rule, is divided into compartments and decorated with reliefs in such a way that all free space is occupied by symmetrical images. The main images or waist portraits of the dead in a round frame are often placed in the middle, in the corners there are buildings, trees, ceremonial seats or decorative figures corresponding to each other. Images often follow one after the other without a break, so that the boundaries of individual plots are determined more with the mind than with the eye. But often the relief is dissected in a vertical direction, usually by means of arcades, and sometimes trees; there is also often horizontal dismemberment, which gives two tiers of images. In the high relief decorations of the post-Constantine sarcophagi, echoes of ancient art are still noticeable. Winged little geniuses hold round frames of portraits; Cupid embraces Psyche; "Salt" and "Moon" (sun and month) reign in heaven. On one sarcophagus of the Arles Museum, we see the Dioscuri, symbolizing loyalty. Christian images, undoubtedly prevailing, begin, as we have seen (see Fig. 7), with the Good Shepherd and other symbols, then, in essential ways, they adjoin the catacomb cycle and gradually turn into whole series of compositions on biblical themes. On the sarcophagi there are now plots alien to catacomb painting; from the Old Testament, for example, the Creation of Man, the Expulsion of the Progenitors from Paradise and the Taking of the Prophet Elijah to heaven, depicted on the side of a Roman sarcophagus kept in the Louvre Museum; from the New Testament, for example, Christ in the temple, the Judging of Judah, and the Ascension of the Lord, connected in one Vatican sarcophagus with the image of the sky in the form of an arc over the head of a human figure, personifying the earth. However, the Crucifixion is still absent on these sarcophagi, most of which belong to the years 350–500. All sarcophagi VI. already distinguished by poverty or rude forms.

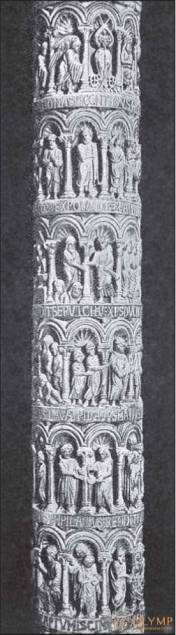

Fig. 50. The sarcophagus of Julia Bassa in the Vatican Grottoes in Rome. From a photo of Danezi

Very curious is the sarcophagus of Julius Bass, published by Grisar (fig. 50), kept in the gloom of the Vatican Groths. The inscription on it indicates the year 359, but, according to Wrigl, not the year of the sarcophagus, which is probably older, but the year of the position of the deceased in it. The relief images decorating it, arranged in two rows, one above the other, and separated from each other by twisted columns, represent figures of still good work and noble proportions. In the upper middle field sits on the throne a young Savior; under his feet is the sky, depicted as a veil, swelling over the head of the heavenly God in an arc. In the lower middle field, the entry of the Savior into the earthly Jerusalem is represented.

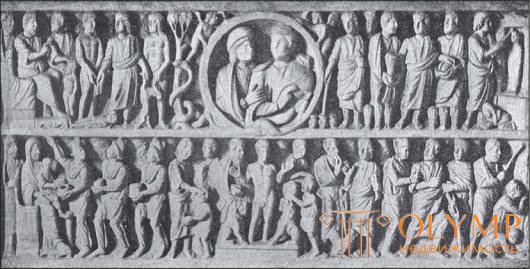

Among other Roman sarcophagi, let us point out the later sarcophagus of the Lateran Museum (according to Ficker Number 104), which was once in the church of Sts. Paul (Fig. 51). The middle of the upper band is a round frame with portraits of the married couple for which the sarcophagus was intended. Biblical scenes, revealing already some parallelism in the alternation of Old Testament plots with the New Testament, follow both in the upper and in the lower row one after another continuously; the distinction between one scene and another is only that their adjacent figures are turned back to each other.

Fig. 51. Roman Christian Sarcophagus in the Lateran. With photos Alinari

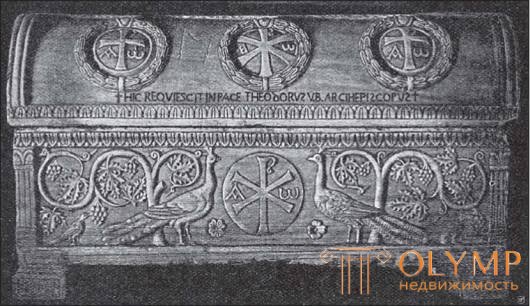

Southern France is particularly rich in Christian artworks of the genus under consideration outside Rome. These works are glorified by the publications of Le Blanc, who paved the way for their study. In Arles alone, there are 79 Christian sarcophagi, closely resembling the Roman sarcophagi, while 16 Toulouse and 8 Narbonne sarcophagi differ from the first in their tapering shape. But in Italy, the ancient Christian sarcophagi are not preserved in Rome alone. 11 are in Campo Santo in Pisa. Ravenna sarcophagi are numerous and distinctive. Already they alone convince in the impossibility of looking at the Equal Art as the successor of the Roman. In their general form, high covers, resembling shingles and timbered roofs, are most striking; they are often decorated with monograms, crosses or wreaths. Then in their images there is no Roman crowding. Biblical scenes, consisting of a small number of symmetrically arranged figures, are usually scattered over the smooth surface of the plate, and the choice of subjects is very limited. Often, in the middle of the front side, there is only the Savior standing or seated on a throne, to whom saints with scrolls or crowns in their hands, covered with the edge of clothes, approach from both sides; All relief space is limited by palm trees and characterized as a segment of the universe. On the sides there are sometimes presented, as, for example, in one sarcophagus of the Ravenna Museum, biblical events. The place of the Savior is often occupied by the Lamb of God standing on a hill; in this case, the saints on the sides of the Savior are replaced by lambs, as, for example, we see it on the sarcophagus of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia.But instead of the Lamb, there is often just a cross or a monogram of the name of Christ, as, for example, on the sarcophagus of St. Theodora in the church of St. Apollinaria in Classe, where, moreover, peacocks are represented instead of lambs, and instead of palm trees - winding vines (Fig. 52). Ravenna sarcophagi with figured compositions are generally older than those decorated with symbols alone. It is best seen from them how quickly plastic disappeared after the heyday of Ravenna.

Fig. 52. Sarcophagus of sv. Theodora in the church of St. Apollinaria in Classe in Ravenna. From the photo of Ricci

Closely limited, although rich in itself, the artistic field of plastics is represented by small ancient Christian ivory carvings, among the products of which the main role is played by double boards (diptychs), individual plates and rectangular or round boxes. Shtulfaut tried to distribute the most important of the early Christian ivory works in Roman, Milan, Equal and Montai schools. But this division cannot be established in reality. Going through the labyrinth of research in this area is currently the most reliable under the guidance of Greven and Føge.

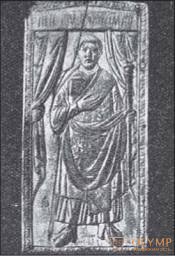

Fig. 53. Diptych Consul Felix 420 g. According to Venturi

Fig. 54. Pilate, transmitting Christ to the people. Ivory carving. From the photo

Of the diptychs, the inner sides of which were intended for writing, and the outer sides were embellished with carvings, the so-called consular diptychs were the heritage of pagan Rome. Consuls and other government officials gave away diptychs decorated with their portraits during solemn and festive days. The consul diptych Antion Sample in the sacristy of the Aosta Cathedral belongs to 406, and a board from the diptych Consul Felix in the Paris National Library belongs to 420 (fig. 53). On this board is a portly dignitary in ceremonial dress, standing between the canopy curtains; In the 5th century, probably, also belonged to the four famous plates of the British Museum, which were part of the box, with images of Christ teaching, the Court of Pilate (Fig. 54), the Crucifixion and the Resurrection; the big-headed and squat figures are nevertheless arranged quite well. In our opinion, these reliefs are more Roman than Greek. These and other similar works can be contrasted with the diptych of Galla Placidia in the cathedral sacristy of Monza, with its long and thin figures, executed, obviously, on another soil closer to the Greek East. In general, already a priori it can be concluded that ivory carving originated from Africa, the birthplace of this bone, and originates not from Rome, but from the East. The best products of this kind, even if they are of Roman origin, are undoubtedly made by the hands of Greek masters; For example, the magnificent plate of the Munich National Museum, in the lower part of which depicts the Myrrh-bearing Wives at the Holy Sepulcher, and the Ascension of Christ at the top, on the right, can serve as a model.

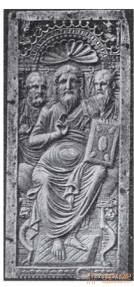

A true Greek-Oriental spirit emanates from the precious tablets of the British Museum of V in. (Fig. 55), depicting a winged angel, inhumanly powerful and at the same time very natural figure, standing on the steps of a luxuriously ornamented semicircular niche. Frequently mentioned diptych of the Berlin Museum, with images of a bearded Savior on one board between the apostles Peter and Paul (fig. 56), and on the other, the Virgin Mary, sitting on the throne between winged angels, belongs to the 6th century. and is close in style to the equal episcopal seat.

Fig. 55. Winged Angel. Ivory carving. From the photo

Fig. 56. Savior with the apostles Peter and Paul. Relief on ivory. From the photo

A number of similar works may be, with a considerable degree of probability, included in the Syrian-Egyptian circle. Syrian-Egyptian recognize, for example, a small oval ivory box in the Berlin Museum, with reliefs depicting episodes of the young years of the Savior. At the head of the Hellenistic-Alexandrian products of this kind you need to put the famous pixid of the Berlin Museum, dating back to the IV century; on one side of it a subtle relief depicts a young Savior among the apostles, on the other - the Sacrifice of Isaac. Some of the best Hellenistic-Alexandrian products of a somewhat later time include the imperial diptych board in the Louvre Museum, which comes from the Barberini collection in Rome, depicting the emperor — probably Constantine the Great — on horseback as a winner in the struggle for the holy faith. Alexandrian-Byzantine can be recognized relief of the Cathedral of Trier, representing the transfer of relics to one of the Constantinople churches; already Egyptian-Coptic recognizes Strigovsky carved "board of Christ" Ravenna Museum with very elongated figures. And in this area scientific research has not yet said its last word.

Fig. 57. Bronze medal with the images of the Apostles Peter and Paul. By Venturi

Ancient Christian metal products of artistic significance are less common than good bone carving. Among the silver vessels, the place of honor was opened in 1894 by the quadrangular vessel of the church of San Nazaro in Milan, rightly attributed to Greve Hellenistic East. The lid depicts the Savior between the loaves and the fishes, on four sides, the Mother of God and the three Old Testament scenes, still half in a promising manner. The magnificent early Christian bronze medal, belonging to the Christian museum of the Vatican (Fig. 57), depicts the characteristic heads of the apostle Peter, with short hair, and the apostle Paul, with a bald head. One of the most beautiful bronze lamps of the time in question, having the appearance of a ship with a sail, is in the Uffizi Museum in Florence. The helmsman of this vessel symbolizes Christ; on the nose is a praying sailor. Decay and change of forms in works of applied art occur everywhere according to the same laws as in large purely artistic works. Only where the new world of forms encounters the old, can we expect new revelations. Therefore, we need to take a quick look at the German North, which followed its own way in this particular area. Westgothic, Langobard and Frankish metal products of the 6th and 7th centuries. testify to the existence of internal communication in all the German applied art of this era, still akin to the art of primitive and semi-cultural peoples.

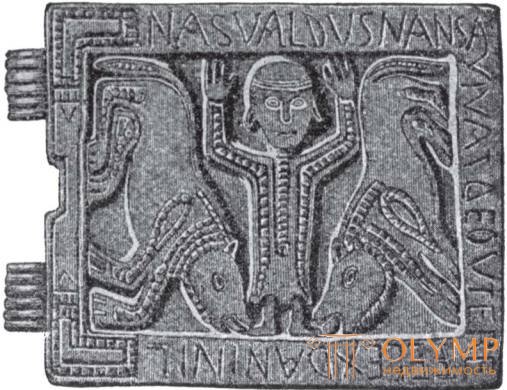

Fig. 58. Daniel is between two lions. Metallic decoration of the era of the Merovingian. By lindenshmit

In German metalwork of this time, which served religious purposes, Christian symbols and figured images are only occasionally mixed with the ornamental motifs of the pagan era of Merovingian art that we know (see t. 1, fig. 546). On the one hand, luxurious, but rough, probably in the Sassanian kingdom, cellular glaze (verroterie cloisonnee), in which the pattern is usually made of red stones or glassy pastes separated by metal partitions, is used to decorate metal plaques; Old Germanic irregular belt or belt braid with the heads of animals, along with which triangles, diamonds, circles, discs, sockets and a new type of weaving with wide loops appear, while leaf foliage, failures but imitating antiquity, is found only in the Merovingian francs, moreover only on the eve of the Carolingian era. By the end of the 6th century, the golden crown of the Lombard Queen Theodolinda, richly decorated with red stones, dates back to the sacristy of the Cathedral of Monz; VII century. they belong to the related Westgoth crowns at the Cluny Museum in Paris and at the Royal Arsenal (Armeria Real) in Madrid. On the one hand, in the Merovingian graves, flat Christian crosses covered with ancient pagan ornaments are found, on the other hand, they are decorated with ancient Christian figure figures. How shapelessly these last were performed, shows, for example, the image of Daniel in the den of a lion on a single plate found in the graves of Lavigny (Fig. 58); but the principle of symmetric filling of a quadrangular surface is here observed with an inviolable sequence. Products of goldsmiths belonging to that part of the Frankish state of the Merovingians, which is now part of France, are especially famous. Bishops competed here with the royal court in decorating churches with jewels. This is not enough: in the face of St. Eligiya, Bishop of Noyon (588–659), we meet here an artist who enjoyed great fame. Goldsmiths still consider him their patron. Until the French Revolution there were still magnificent works that came out of his hands, for example, the bowl of the church of the Shell Abbey, near Paris. Masterpieces of sv. Eligiya were canopies over the tombs of St. Martina on Tour, St. Genoveva in Paris and of sv. Dionysius in Saint-Denis. Of the still existing works of St. Eligiyu is credited with the lower half of Dagobert I’s throne at the Paris National Library. In addition, in many churches in the north-east of France, altar decorations (retables) and reliquaries are preserved, reflecting its artistic direction. On them, clumsy figures are also quite common, but in general they all stand on the basis of Merovingian ornamentation. Already works of this kind make us feel that the vocation of Central Europe was to put Christian art face to face with new tasks.

The history of Christian art before the 8th century reminds us of the “white night” of those countries where the evening dawn merges with the morning. The evening dawn of Roman-Hellenistic art was at the same time the dawn of Christian art. In the post-Constantine epoch, the main European centers, Rome, Constantinople, Milan and Ravenna, for some time kept apart from each other, each developing their own artistic influences coming from the Hellenistic and Far East. That Rome, the spiritual capital of the Christian world, did not take any part in the formation of Christian art is certainly incredible; one glance at the Roman catacombs, basilicas, mosaics and sarcophagi is enough to guard us from underestimating the artistic merit of the Eternal City. But from the fact that in Rome, after its two-thousand-year, almost uninterrupted spiritual dominion over the world, the monuments of ancient Christian art were preserved, it would be a mistake to conclude that Rome was the starting point and main focus of the artistic movement in the time we considered. The reasons that prompted the Roman emperors to move to Milan, Ravenna, Constantinople, prevented Rome from retaining leadership in the arts; on the other hand, the fact that Constantinople became the main political center of the empire easily explains to us why it was here, on the shores of the Bosphorus, the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara, that artistic impulses coming from Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt resulted in to those transformations of forms that created the Byzantine style, and then laid the beginning of the Romanesque style in the West.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)