Japan is an archipelago of volcanic islands stretching in length, separating the Sea of Japan and the Sea of China from the Pacific Ocean in northeast Asia. By its geographical position, climate and soil, it is among the most blessed of countries predetermined by destiny for the magnificent flourishing of human culture. Nippon Island - “The Land of the Rising Sun”, which nature itself noted by the huge snow pyramid of Mount Fuji (Fuji), almost 4000 meters high, washed by a dark blue ocean, deeply crashing into its shores with its bays, is completely dressed in lush vegetation, in every season which is in a new kind of brilliance, and abounds in general with the beauties of nature, acting on a receptive person, elevating his spirit and evoking in him a creative mood. And indeed, the Japanese, a tribe of Mongolian origin, who had subdued in prehistoric times, the primitive population of the main of these blessed islands, the Ainu, and pushed them northward, managed to express their sense of nature and artistic flair in an extraordinary combination.

Europe learned about Japanese art in the 1930s. XIX century. And its rapid spread in it was a real triumph. In all parts of Europe, it not only found its ardent admirers and praise generous admirers, but also had an influence on the course of European art and especially on the art industry. Moreover, our connoisseurs, artists, and collectors humiliated Chinese art to the same extent that they exalt Japanese art; but in most cases this was due to incorrect assumptions and, above all, because Japanese art became known to Europe much better than the ancient Chinese. In Japan, the most ancient works of art for the most part were not made, as in China, the victim of the spirit of destruction that accompanied the changes of dynasties. The Japanese did not try, like the Chinese, to conceal the artistic treasures stored in their temples, palaces and public collections from the eyes of Europeans, but willingly opened access to them, at least since the coup d'état of 1868. Moreover, in the first decades, At one time, the Japanese who followed this revolution neglected to such an extent the ancient works of their national artistic creation that they distributed them to European collectors with a generous hand. Thanks to this, thousands of small Japanese plastic items, scrolls, paintings, picture albums, and hromo-xylographs got into the American and European collections. In Europe, already in 1830, Leiden owned a collection of more than 800 Japanese scrolls of drawings. In the British Museum in London in 1882 a collection of 2 thousand Japanese and Chinese paintings and color engravings was formed. From the same time in the Berlin Museum of Art and Industry there is a collection of 200 samples of Japanese painting. In Paris, some private collections (Gonze, Bing, Vever, etc.), as well as the Guimet Museum, are particularly rich in treasures of the Japanese art industry and polychrome wood engraving. Many curious in the same part contain the Berlin and Dresden engraving rooms, and the Hamburg Art and Industry Museum can be proud of its collection of samples of all kinds of Japanese art. But America has the largest number of them. Her private collections (Morse in Chicago, Vanderbilt in New York, Phenollosis in Boston) are so extensive that they cannot be reviewed. The largest Japanese collection in the world is in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts: it contains over 400 wall screens, 4 thousand paintings and 10 thousand engravings of the Land of the Rising Sun. Managed this museum E.-F. Phenollosis, who for 12 years headed the art institutions of Japan, was considered the best connoisseur and hardest researcher of Japanese art.

It should be noted that this art is presented better than the Chinese, not only in our museums, but also in our literature: Siebold's old work "Nippon" is still worthy of reading, at the end of the XIX century. detailed works on the Japanese art of Gonze, Anderson, Bing, Brinkmann and Munsterberg, monographs of Phenollosa, Edm. de Goncourt, G. Hircke, T. Dure, Carl Madsen and V. von Seidlitz, who contributed to our closest and accurate acquaintance with the art of Japan.

The further progress is made in the study of the history of Japanese and Chinese art, the more obvious it is that the Japanese art of all previous centuries owes much of its charm to Chinese art, its undisputed progenitor. As early as 1822, T. Dure asserted that Japanese art was Chinese, like Roman Roman was Greek; found the same and fr. Geert. Phenollosis, an ardent admirer of ancient Japan, expressed in 1884 that we are not at all mistaken if we consider that in Japanese painting all are of Chinese origin, of course, with the exception of a few, but sometimes magnificent, truly Japanese deviations. Attempts by some French scientists to provide the main role in the development of Japanese art to direct Indian and Persian influences should be considered unsuccessful.

Be that as it may, there is nothing unheard of that the daughter turns out to be more beautiful than her mother. Even if Chinese art were as accessible to study as Japanese, we probably would have remained with the opinion that this last differs from the first with a deeper sense of nature, a more subtle understanding of colors, a more elegant taste, more good-natured humor In particular, the Chinese can give the palm in the processing of hard stones, porcelain production, cellular enamel making, and the Japanese in lacquered products, chromalography, small artistic and metal works. In general, it is clearly seen that in Japanese art and craft production, art and the requirements of life are interconnected even more closely and more meaningfully than in Chinese. Arts and crafts are nowhere in such inseparable interconnections as in Japan. Gonze is right to write at the beginning of his great work on Japanese art the phrase: "The Japanese are the first ornamentalists in the world." But also the sense of nature and the sense of style are nowhere interconnected so inseparably as in Japanese art, and due to the close connection of these feelings that are in the blood of their masters, the Japanese should be recognized as one of the most artistic peoples in the whole world.

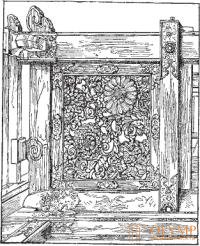

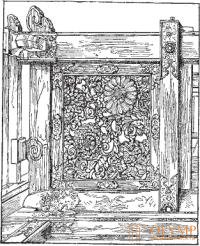

Fig. 604. A door fence, ornamented with chrysanthemums, in one of the Kyoto temples. By Brinkmann

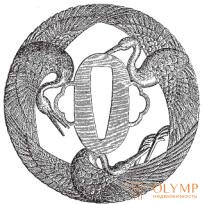

So, the Japanese ornamentation in its basic features and main components increased on Chinese soil. Although in Japan, as in China, there is no shortage of geometric lines in the game, in patterns consisting of a swastika and a meander, in whimsically curved and intermittent ornamental motifs, but here, as well as there, the main thing are animal and plant forms, often closely interconnected. Of the animals in Japan, as in China, the feathered inhabitants of the airspace, and then the scaly and armored inhabitants of the seas and, finally, amphibians and insects, enjoy special love. Representatives of flora in Japan are predominantly bamboo and pine branches, spring flowers, peonies and chrysanthemums (Fig. 604), and everyone agrees that the Japanese can distribute their more or less stylized animal and plant motifs on an ornamented surface with even more dexterity , with even less concern for strict symmetry than the Chinese. But next to the real world of animals and they have fantastic creatures inherited from China: the dragon, the phoenix, the fairytale deer, and so on; the dragon plays the main role, although it does not serve as a symbol of imperial power, as in China, and therefore has not five, like the Chinese imperial dragon, but only three claws on each paw (fig. 605). The symbol of imperial power in Japan is a stylized chrysanthemum flower, unfolded in the form of a wheel, a kind of daylight, illuminating the rays of the rising sun with its rays.

Fig. 605. The reverse side of an old Japanese metal mirror from Nara. According to Anderson

Japanese architecture is even more than Chinese, comes down to carpentry.

Stone walls in Japanese buildings are rare. In these buildings everything is wooden. Strong walls are often not available at all. Even instead of external walls, there are often moving walls that can be inserted or removed, if desired. Inside the houses, instead of them, they are content with folding partitions and screens. The characteristic Japanese tile roof, strongly protruding its edges forward, is supported by a whole labyrinth of wooden supports in the form of sconces. The roofs of houses, as well as the ancient temples of Shinto, are usually straight. However, the Buddhist temple construction transferred to Japan, along with the multi-tiered pagoda towers, also Chinese roofs with curved edges (Fig. 606), and from the Buddhist temples such roofs were later borrowed by other buildings. In Japanese houses and ancient Shinto temples, we see in all its beauty the natural color of wood. The greatest purity and accuracy of carpentry and lathe work, the fit of thorns and nails, in which the latter are often finished artistically, the grace of decorative carving, painstaking processing of all particulars with surprising love often give a simple carpenter constructions of this kind to the character of completely finished artistic works. But where it is customary to resort to painting, such as, for example, in Buddhist buildings, it is warmer and more harmonious than in China. Japanese torii, symbolic simple gates in front of the temples, not similar to Chinese pass-lions, retained the old wooden structure. Two vertical pillars are interconnected from above by two transverse logs. As an exception, you can only point to the large torii of the Ieyasu temple in Nikko, made of stone and bronze (fig. 607). Finally, Japanese architecture, like Chinese, has a tendency to combine many rooms into one organic whole. If there is a need for several halls, they are arranged next to each other in the form of special houses; large buildings of this kind, joined into one strikingly beautiful whole by one common magnificent garden, are usually located not so primly symmetrical as in China. What is most charming in Japanese architecture is the magnificence of parks with large temples and palaces, with high flowering shrubs, with rocks, waterfalls and fountains, with pedestals for lamps and statues; these parks could be called works of landscape architecture, although in another, but perhaps in a more precise sense of the word, than Indian structures in the rocks (see Fig. 565).

Fig. 606. Temple near Osaka. From the photo

In Japanese large-scale plastics, we also find only numerous sacred images of Buddhism, and, moreover, always in a strictly frontal position, while all other sculptures of the same time and earlier, even the oldest surviving ones, are distinguished by complete freedom of all motives of the movement. Japanese Buddha images are of the Gandharic type, given to the Hellenistic Old Indian. The roundabout path through China and Korea, which the religious large plastic of Japan went through, thus did not blot out signs of the original origin of this branch of art. Finally, it is remarkable that Japan has preserved the world's greatest bronze statues of Buddha, even more enormous than in China - proof of the Japanese desire to bravely cope with major tasks.

Fig. 607. Torii Ieyasu temple in Nikko. From the photo

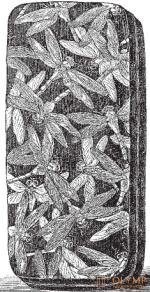

As for the Japanese small plastics, then you can write entire volumes about it. None of the art industries to the extent that in this one, the Japanese do not show all the subtleties of their sense of plasticity, their ability to use the forms of nature and stylishly adapt them to the purpose of the work. This is evidenced by products from all sorts of materials - from bronze, iron, wood, ivory, baked clay, lacquered works, things made from several different materials, and in various ways, and painting, used in this form and with such taste only some Japanese. These are small statuettes and groups that do not have a specific meaning and purpose, the Japanese call such things okimono, then all sorts of everyday objects, of which the special cups of swords and netsuke, worn on belts for attaching any kind of objects, are especially respected by our collectors. . On them we find images of people, animals and plants, now alone and alone, then in their daily mutual relations, communicated good-naturedly and with humor - small artistic things, distinguished by a subtle sense of nature and poetic mood. The abyss of diligence inspired by love to work, the abyss of creative imagination, the abyss of individual artistic freshness are manifested in these purely Japanese works. How carefully avoids the Japanese sharp corners, making netsuke, because of his appointment! With what taste he has on the sword's cup the through or laid-on work of the figures of plants or animals, especially spiny lobster, fish, snakes, adapting them to the roundness of the product! This can give the concept of rice. 608 - Netsuke in the form of a snail, the work of Tadatoshi (from the Bing collection in Paris), and fig. 609 - a sword cup with figures of cranes (from the Hamburg Art and Industry Museum). Brinkmann wrote: “There is nothing surprising in the fact that a worker on metal, wanting to depict his favorite bush of nantes on a wrought iron cup of a sword, plays gold branches and leaves with inlay on it; but he supplies these branches with red berries, for which he cuts hollows in the gland and puts pearls or corals in them, or he places on the iron plate an image of a locust, one of the symbols of military courage, made of multi-colored metals, and in order to make expressively the greenish, brilliant, bulging eyes of this nation washed, inserts pieces of polished malachite into his head. Or, finally, he conveys the variegation of autumn leaves of pumpkin, inserting pieces of variegated mother of pearl into a bronze or gold minted plate. wooden dolls, or on a branch of chrysanthemums carved from ebony, puts silver circles of flowers in a wreath of black extreme flowers, or on a lotus leaf carved from wood, strengthens a metal frog of knocked-out work, or revived a carved wooden vessel, depicting an old pine tree trunk, small gold and silver ants. "

Fig. 608. Netzke in the form of a snail. Work Tadatoshi. By gonze

Fig. 609. Sword cup with cranes. By Brinkmann

Actually, Japanese painting , if one does not touch upon the last development of its folk school, cannot be described otherwise than its ancestor, Chinese painting. Many of the most famous Japanese paintings, in European view, are no more than black drawings made with brush and ink. Traces of the origin of painting paintings from illustrations in manuscripts did not disappear as it crossed the Sea of Japan and China. Japanese sources give us the opportunity to trace the calligraphic basic character of Japanese painting, as well as Chinese, in all its changes. Based on one of these sources, Anderson introduced us to ten classical kinds of calligraphic brush drawing, which we discussed in the previous chapter. Lines thin, of equal width, calmly and without any pressure going along the contours of the figures, characterize the drawing technique of the first kind (Fig. 610, a); in the second kind, the contour lines have the form of short strokes, breaking under a sharp or obtuse angle, with thick wedge-shaped presses (b); in the third kind, the lines are rounded, with larger or smaller bulges, depending on the requirements of the drawing ( c ), etc. Japanese art historians are able to classify all famous Chinese and Japanese artists on the basis of these differences, which, however, are found only in the performance of costumes. After what has been said, it is hardly necessary to state once again that multicolored Japanese painting, again if one does not take into account attempts made in the last great era, suffers, like Chinese, with the absence of shadows and reflexes, shortcomings of light and shade, errors against anatomy and prospects. Body shapes everywhere deliberately appear flat.

Fig. 610. The first three kinds of Sino-Japanese drawing. By anderson

Fig. 611. Inkwell with inlay. By gonze

Separate Japanese paintings, like Chinese, are in the form of scrolls that are hung on walls unrolled from top to bottom (in Japanese, they are called kakmono), or desktop scrolls that unfold from right to left (Emakimono); In addition to such pictures, the Japanese also have folding harmonicas and forming something like an album. Fixed parts of the walls in temples, palaces and homes are rarely decorated with paintings; they are often placed on walls that move apart like shutters, and even more often they are found on movable walls, which, having the appearance of screens, are an important attribute of Japanese household utensils. Such screens were sometimes painted by the greatest artists.

As transfers of painting to other technical branches, varnishing, embroidery, painting on vases and woodcarving are worth attention first of all. Japanese products of these four species belong to the most perfect of their kind. Artists-lacquers are able, without sacrificing the fineness of a flat or relief image at all, to enhance its decorative impression with the use of gold, silver, mother-of-pearl, ivory or coral. The inkwell from the Gonze collection in Paris (fig. 611) is decorated with an image of a whole swarm of dragonflies made of tin and mother-of-pearl and set in black lacquer. Embroiderers, reproducing charming pictures of nature with a magnificent mood with the help of colored silk on silk fabric (fukuss), sometimes take up the brush in order to enhance the impression of the image. Japanese potters, as opposed to Chinese painters on porcelain and their imitators in the Japanese province of Gitsen, achieve spectacularity with a bold and wide reception of their decorative pictures of nature in simple, harmonious colors. Chromalography is so important in modern Japanese folk art that even great masters conceived many and their best images so that they were initially reproducible in a large number of copies by printing from several boards (see Fig. 633).

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)