For the ancient Greek metropolis, the Hellenistic era is the age of state decline. Already in 146 BC. e. Rome ruled throughout Greece. But the winners on the battlefield immediately felt defeated in the field of scientific and artistic competition. The arts in ancient Greece then experienced a secondary flourishing, albeit under the influence of the world-wide Hellenistic art of the giant cities of the East, but retaining their spirit and their own coloring. In the intellectual life of the metropolis the leading role belonged to Athens and Olympia. In Asia Minor, the city of Attalides Pergamus became at that time the head of the movement. In the struggle against the Gallic hordes that were advancing from the north, the Pergamon state gained its independence, the Pergamon rulers acquired the royal crown. The era of the two first kings of Pergamum, Attalus II (241-197 BC.) And Eumenes II (197-150 BC.) - the heyday of this modern Greek state that emerged on the ancient Modese soil, has long been Ionian influence. In terms of education, Pergamon competed with Alexandria. The library of Eumenes II aroused the envy of the Ptolemies to such an extent that they even forbade the export of papyrus from their possessions. But the parchment people managed to get out of the difficulty: they invented parchment and began to use it instead of papyrus.

If the progress of art in the Hellenistic time on the Nile, Oronte and Tigre, we can only build assumptions based on written sources, rather than get a clear idea with the help of detailed data, then on the ancient Hellenic soil in the Greek metropolis, on the islands and in Asia Minor, we have rich material.

We know a lot about the Hellenic architecture of that time. Following the German excavations at Olympia, the excavations in Pergamum were carried out under the direction of Karl Humann, described by Konets, Humane, Bon, Lolling, Stiller and Rush. We owe the first our information about Ancient Ephesus to the Englishman Voodoo, and a compilation of all the data relating here was made by G. Weber. Among the French, who led the excavations on the island of Delos, Gomoll takes an outstanding place. The sanctuaries of Samothrace became known thanks to the End, Gauzer, Niemann and Benndorf.

Fig. 442. Capital of the Samothrace column. By the end

Bon and Shuhardt worked on Aegea. German scientists conducted research in Priene, and the British, Germans and French labored to finish the excavations in Miletus.

Stopping above all on the use of the vault in these ancient Hellenic areas, we must say that the vaulted vault above the entrance to the Olympia lists, built around 100 BC. e., especially after research Noak, can not still be considered the oldest on Greek soil vault, composed of wedge-shaped stones. A whole series of later arches became known, of which the oldest in the city walls of Acarnassus belong to the V century BC. e. In the Hellenistic era, this method of construction began to be used more often, namely, first in the lower floors. The ground floor of the “Ptolemyon” on Samothrace was equipped with an entrance with a beautifully folded vault, while the Temple of Athena Polias in Pergamum rested on the correct canopy vaults. That when building the upper parts of buildings, at least in Athens, for a long time, they feared to reduce the arches of wedge-shaped stones with a lock, can be seen through the arches of the aqueduct of the so-called Tower of the Wind, carved in one layered horizontal beams. On the contrary, the main hall of the gymnasium in Ephesus, belonging to the Hellenistic era, was covered with three cross vaults.

Be that as it may, in Greece, on the islands and in Asia Minor, until the end of the Roman Republic and later, the main task of architecture was the erection of buildings with columns and stone beams entablature. At this time the temples were completed, rebuilt and re-erected in the ancient style. The Doric and Ionic orders, as before, were subject to change, but where their treatment was not free, they took on more and more weak, dry forms. Take a look at what a sharp straight profile Ekhin has during his transition to the abacus in the capitals of the columns of the new Doric temple on Samothrace (Fig. 442). Pay attention to the shape of the southern Doric colonnade in Olympia. Look at the Ionic propylene columns in Priene, which belong to a later time than the columns of the temple itself. The Corinthian Order has now become boldly appearing in the outer colonnades: we find it fully developed in the columns of the gigantic temple of the Olympic Zeus at the foot of the Athenian Acropolis, a building that stood unfinished from the time of the Pisistratids; in 174 BC. e. its construction was resumed by the Roman architect Cossucius at the expense of the Syrian king Antiochus IV, and yet was not completed. We see the Corinthian order remarkably simplified (about 100 BC), with pointed reed leaves above the lower crown of acanthus leaves on capitals, in both porticos of the octagonal Tower of the Winds in Athens, and, finally, richly decorated with antennae, flowers, berries and figures of chimeras on the capitals of the ants and columns of small propylene in Elevzis, erected in 48 BC. e. Appius Claudius Pulcher (Fig. 443).

Fig. 443. Eleusinian capital with chimeras. By von Siebel

Fig. 444. Palm-shaped capital. By the end

One of the innovations borrowed from Oriental art is, for example, the palm-shaped capital (Fig. 444), belonging to the columns of the inner side of the colonnade from the Attalus II gallery in Pergamum and apparently originating from the Egyptian palm-shaped capitals. The same innovation is represented by consoles in the form of bull heads in the market colonnade in Aegheus and capitals with bull heads in Ephesus and on the island of Delos, inspired by similar Persian capitals (see. Fig. 237). On Delos, they are located in the eastern gallery of the Temple of Apollo (Bull Gallery, fig. 445). Here the capitals, equipped with outstanding bulls front-facing buildings, were decorated with pilasters, to the back side of which Doric semi-columns were attached.

The peculiarities of the architecture of the time in question include the frequent mixing of the main components of the Ionic and Doric orders. In the large two-story gallery in Pergam on the top floor, we find a triglyph frieze above the Ionic columns. The flutes on the Doric columns of one building on the Market Square in Priene and the rather ancient temple of Demeter and Kora in Aegheya are separated from each other by ionic ribs (fig. 446).

Then, as new forms of another kind, you need to point out the octagonal bases of some of the Ionic columns of the Didimian temple of Apollo in Miletus, which was still under construction at that time, on the frieze with bull skulls and rosettes in Ptolemyon on Samothrace, and on the frieze with wreaths and bull skulls in Egea .

Fig. 445. Pilasters with bulls heads in a building on the island of Delos. By durmu

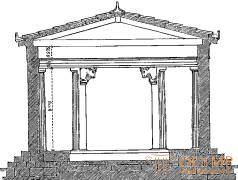

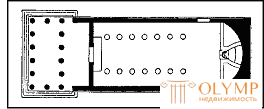

The Hellenistic era on Greek soil brought some features and novelty to the very plan and construction of buildings. At Samothrace at the very beginning of this epoch we find an elegant Arsinoe round building, similar to the Olympic Philadelion and the round building in Epidaurus, but different from them in its two tiers: the upper parts of the walls are decorated with Doric pilasters on the outside, and inside the Corinthian semi-columns, the bottom is decorated with bull skulls and rosettes. Even more distinctive is the marble Doric temple (Kabirov temple) in Samothrace (Fig. 447). It has a portico on the columns only from the front side, and its cellulose, divided into three naves and inside a semicircle ending at the back wall, resembles an ancient Christian basilica.

Fig. 446. Capital from the temple of Demeter in Aegean. By bon

In Pergamum at that time there already existed a large magnificent altar, built, in all probability, by Eumenes II (197-150 BC). The lower part of this building, in which a wide staircase went deep into the west, was about 30 meters squared. All four sides of this part and the walls of the staircase were decorated with huge high reliefs, the salvation of which glorified the German explorers. On the upper square, under the open sky, stood an altar, surrounded by a beautiful, open outside gallery with Ionic columns, in which there was a break only for the stairs. The wall of the gallery, facing the altar, was, in all likelihood, decorated with a strip of smaller reliefs, fragments of which were found right there. A further stage of development is presented to us by a two-story gallery with columns, built by Attal II (in 159-138 BC) in the temple square of Athena Polias, in Pergamum. The lower gallery, divided into two naves, had outside Doric, and inside the above-mentioned smooth-bore palm-shaped columns (see. Fig. 444). The upper gallery consisted of Ionic columns, of which we also spoke, with a Doric triglyph frieze.

At Olympia, the Philippineon (see Fig. 382) was a transition to the buildings of the Hellenistic era, among which the Palestr and the gymnasium are particularly remarkable. Palestra was decorated with Doric, Ionic and Corinthian colonnades. Between it and the gymnasium a special building of the gate of the Corinthian style towered, with a plan of propylene. The gymnasium on the east side ended in a gallery with Doric columns, divided into two naves and more than 200 meters long.

Fig. 447. Plan of the Kabirov temple in Samothrace. By Niemann

In Athens, on the eastern side of Kerameika, was built by Pergamon king Attalus II standing, bearing his name; it was a kind of market, 112 meters long, in two floors, of which the lower had Doric outside, and inside Ionic galleries. The aforementioned Tower of the Winds, in fact, the "horologies" of Andronicus of Kirry, are remarkable in their octagonal shape; in it were water and sundial. We have already spoken about the Corinthian columns of its porticoes. The novelty in it is a semicircular tower-like extension on the south side and bas-reliefs depicting eight main winds in the form of human figures in full size and placed on top of the outer surface of the eight walls of the tower; finally, the original roof itself is made of marble slabs and has the shape of a low octahedral pyramid; on a round stone crowning the roof, a weather vane stood in the shape of a Triton, which, rotating, indicated the direction of the wind.

Theaters studied in the XIX century, were in different locations. Instead of a moving, changing wall of the background, it is now customary to arrange a solid, fixed proskenion, between the columns of which wooden pinakes were put for hanging decorations. Because of this, the paraskenion lost its meaning, and it was possible to manage without it. However, the presentation was still in the orchestra, before slipping. Only in the Roman era was the scene added to it, logeion. The numerous theater buildings that had Hellenistic prospection (in Eretria, Oropa, Piraeus, Sicyon, on Delos, in Magnesia on Meander) should be attributed to the Hellenistic theater of Dionysus in Athens.

We can comprehend the general brilliant impression that lively Greek cities with their buildings, rich columns and gables, with small round buildings adorned in the Hellenistic era, can be found in German excavations at Olympia, Pergamum and Priene. Restoring the general appearance of these cities, of course, we must mentally remove from them the buildings of the Roman Empire, as long as we want to imagine these cities in their Hellenistic greatness: for example, the exedra Herod Attica should be excluded from the overall picture of Olympia, Traianum, the highest of his temples; but what remains after these exceptions is enough to imagine the architectural and picturesque splendor of the Hellenistic cities. Olympia occupied the whole valley and its slopes with luxurious buildings that for centuries formed an organic whole; Pergamum is a mountainous city, which in a short time grew and formed several terraces, one above the other; Priene - Hellenistic, as if poured from one piece of the city, located on an artificially leveled space, rising from sloping terraces, it could be proud of its streets, crossing at right angles; rectangular Market Square, on three sides furnished with colonnades; a public meeting building that looked like a theater; an exemplary Ionic temple, founded under Alexander in honor of the patroness of the city of Athens, with the help of which it was expanded and decorated.

Hellenistic art in the Greek metropolis, for its part, also participated in the development of the arts that took place in Alexandria. Proof of this is found in the wall paintings of the third-century tomb opened in 1885 by Fabricius in Tanagra and confirming our assumptions regarding the direction of the development of the arts on the Nile. In these paintings, it is easy to notice the attempts of a perspective image and the transfer of shadows; the drawing on one of the long walls of this tomb was a coherent landscape, from which a house painted perspectively with a flat roof survived, a tent-like building and a palm tree.

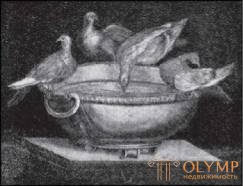

The participation of Pergamum in the further development of painting is more pronounced than in architecture, which affects the decoration of interior spaces in luxurious buildings. Mosaic floors were one of these decorations, and pergamists were famous as excellent masters of mosaic work. The most famous of them was Soz, according to Pliny the Elder, who performed Oikos-Asaratos (Untamed House) in Pergamum. The building received such a name because on this mosaic floor were depicted with the help of small multi-colored pieces of smalt remnants of food and all kinds of litter, as if the floor remained unmarked. "The pigeon drinking water is especially remarkable, and the shadow of its head falls on the surface of the water; then other pigeons bask in the sun or crowded on the edge of the vessel." Quite a lot of free-will imitations of this Pergamon painting have survived. The most famous mosaic comes from the Villa Adriana and is stored in the Capitoline Museum in Rome (Fig. 448). As the “unmarked floor” was generally introduced, we can to some extent make up a concept for the mosaic floor found on Aventine and located in Lateran in Rome. In this kind of images on the floor, imaginary stylishness suddenly turns into a contradiction with style. But the mosaic image of pigeons beautifully testifies to the successes of the painting technique in Hellenistic art. The sculpture of that era in Greece and in the ancient homeland of this branch of art, Asia Minor, seems to us much more active than painting. Pergamum Plastic came out on top. Pergamon sculpture is significantly different from the Alexandrian.

Fig. 448. Pigeons by the water. Mosaic. From the photo

The plots of their historical images were sculpted by the Pergamon sculptors of Attalus and Gauls from the victorious wars. Pliny the Elder said that the sculptors of bronze, Epigon (probably his name was so, and not Ishigon), Pyromah, Stratnik and Antigonus depicted the battles of Attalides with the Gauls. We learned from Pausanias and other writers that Attal I ordered that his beloved city, Athens, be displayed on the southern wall of the Acropolis as a gift to the gods, with figures of full size, Greek victories over giants, Amazons, Persians and Galls. The merit of Heinrich Brunn is that he proved that a significant number of Amazons, Persians and Gauls, obviously belonging to the aforementioned gift of Attal, are now scattered in our museums; that the surviving figures are those that once admired in the Athenian Acropolis. But there are also grounds for assuming that these Athenian marble sculptures are only copies of the lost bronze originals and that these originals, being in size, probably were in Pergamum. It is remarkable that not a single one of the statues of the winners that were part of this group has been preserved, unless it is recognized as such, together with Conrad Lange, one, heavily spoiled equestrian statue of the Neapolitan Museum. The marble sculptures of the already dead enemies of the Greeks of this group include the bearded giant who fell on its back, the Amazons who fell on their backs and fell to their left side, the Neapolitan Museum. Among them, it is necessary to rank the handsome Gallic youth stretching to the full on the back, the Venetian Doge's Palace. Of the number of still falling and partly still fighting figures, mention should be made of two Persians, dropping to the left knee, in the Vatican and the Museum of the City of E, as well as statues of Gauls, two of which are located in the Doge's Palace in Venice (Fig. 449) and one in the Louvre Museum in Paris.In the Gauls' figures, the originality of Pergamon art cannot be more clearly displayed. The coarseness of the forms of the body of the northern warriors, developed not by the exercises of the palestra, but in serious battles, is striking. The surface of the exposed parts of the body breathes strength and a kind of life. The movements are captured in all their accuracy.

Fig. 449. Wounded gall. Marble statue. From the photo

Fig. 450. Dying warrior. Marble statue. From the photo

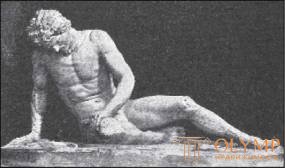

Следует упомянуть о нескольких мраморных фигурах разной величины, которые на основании их сходства по характеру и позам с вышеозначенными статуями можно признать современными им произведениями пергамской школы. Сюда относится прежде всего изваянный из мрамора греческих островов знаменитый "Умирающий воин", Капитолийский музей в Риме (рис. 450). По ожерелью на шее, скрученному из золотой проволоки (torques), всклокоченным волосам на голове, растрепанным усам, тяжелым формам тела, сильно развитым лодыжкам, "жесткой, не гладко натянутой коже" нельзя не узнать в этой фигуре галла, а его поза ясно показывает, что это воин, сраженный в бою. Кровь льется из раны на правой стороне его груди; он упал на бок, склонившись вперед, и, опираясь в землю правой рукой, едва удерживает свое тело. Поникнув головой, он ждет прихода освободительницы-смерти; на его лице – упорство, мука и приближающаяся потеря чувств. Сюда же относится известная группа в натуральную величину "Галл и его жена", музей Буонкомпаньи в Риме. Она прекрасно описана Гельбигом: "Галл, преследуемый по пятам неприятелем, только что успел нанести смертельный удар своей жене в левую сторону груди и теперь поражает самого себя, безусловно смертельно, вонзая себе меч в большую артерию. Левой рукой он еще поддерживает свою умирающую подругу жизни. На его лице, обращенном в сторону преследователей, выражается удовлетворение тем, что ему не попасть живым в руки неприятеля".

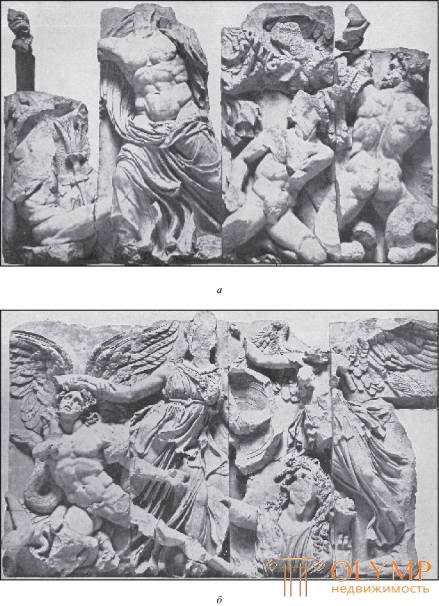

Fig. 451. Fragments of the Pergamon frieze "The struggle of the gods against the giants": a - Zeus is fighting the giants; b - Athena fights with giants

The works of this kind introduce us to a truly new world of art. In the truth of life, the images of foreigners and their folk historical themes would have been unthinkable in the days of Phidias and even Praxitela, although they embody artistic views that have gradually developed since then. We see the same direction in large plastic works that appeared in Pergamum under Eumenes II (197-159 BC). The most important of these works, now the pride of the Berlin Museum, is a large frieze preserved only in many fragments depicting a battle with giants, decorating the lower floor of the altar of Zeus and the walls of his staircase from all four sides (Fig. 451). This frieze, originally 100 meters long and 2.3 meters high, was executed by various sculptors, whose names are unknown, but, judging by the majestic unity of his composition, one may think that he was designed, perhaps, by one person. Favorite Greek art story - the struggle of heaven with the earth, the gods with the giants, has never been reproduced with such vitality and strength, as grandiose as here. On this very high, extremely stylish relief, in which only elements of painting are applied in some places, what are their diversity, the background image, the reduction of body forms, and, however, some figures are completely separated from the background, the most passionate, fierce battle that one can imagine imagine. On the side of the main gods of Olympus, numerous minor gods fight, in part even those with which the fantasy of the later Greeks endowed the sky. On the battlefield, we see a three-faced Hekat with several hands, like an Indian idol. On the side of the well-known main giants, other children of Earth also participate in the battle, whose names, indicated in the inscriptions with their figures, are not found anywhere else. Often the human image, as in ancient Greek art, has only some of the giants, and many of them have a snake body, while others are equipped with one or two pairs of wings. Some have horns, animal ears and claws. Everywhere victory remains on the side of the gods. The giants, to the aid of which Gaia herself appeared in vain, the elderly Mother Earth, are defeated everywhere, some - crying out the air, others - falling unconscious. The snakes that make up the lower part of their bodies manage to wrap their beads around one of the gods or sink their teeth into it. Zeus shakes the aegis with his left hand, and lightning strikes his right with his hand at the king of the giants Porphyrion (a). Athena, seizing the four-winged giant Alkioneya by the hair, draws him behind him (b). Apollo and Artemis, having stepped over their opponents to the ground, are preparing to shoot arrows at other enemies. The strength of the movements everywhere corresponds to the power of bodily forms. The transformation of the old types in the spirit of the new time can be seen here in the figures of the gods, the novelty of the forms is shown in the figures of the giants. The ancient idealism of the Hellenes is reflected in the overall composition, for example, in the monumentality of the location of the heads of the main figures under the columns that surrounded the building above the relief. The realism of the time in question is manifested in the striking naturalness of the movements, the extreme specificity of all forms, the warm life truth of the surface of all naked body parts. Mostly traces of paint remain, proving that Greek marble works were once illuminated with different colors. Here paints contributed to concealing some weak points in transitions and angles. In general, the Pergamon “battle with the giants” testifies to the still high state of Greek art, and therefore there is nothing surprising in the fact that in the later period of ancient culture it was counted among the wonders of the world.

Fig. 452. The female head found in Pergam. According to Kekule

The frieze on the inside of the upper wall of the same building, located in the Berlin Museum, is devoted to images borrowed from the Pergamon heroic legends - according to Robert, the myth of Tele. In this work, the spirit of time manifests itself differently, but as clearly as in the “battle with the giants.” The relief of this frieze was executed in the picturesque manner of the Alexandrian reliefs. Landscape nature backgrounds, different depth of the hollow parts, different height of the bulges and bold views make up the features of this frieze.

Of the interesting works of Pergamon sculpture, one must first of all point to the beautiful female head, in which, more clearly than anywhere else, a change in style that has occurred since the times of Praxitel (Fig. 452) is shown. “The separate parts of this head,” said Kekule, “are perfect no less than the parts of the head of the Praxitele Hermes, and they are one inseparable whole; in the picturesque respect they harmonize with each other.”

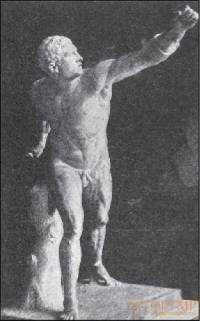

Fig. 453. Borghese fighter. From the photo

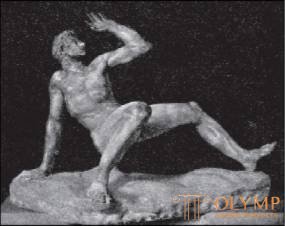

Of course, Pergamon art should have been reflected in the art of the rest of the cities of Asia Minor. Under the influence of the Pergamon frieze, a small frieze depicting the “battle with giants” was found, found near the Temple of Athena Polias in Priene and stored in the Berlin Museum. The picturesque landscape character of the smaller Pergamon frieze is developed in relief, located in the British Museum and representing the apotheosis of Homer, in the work, as the inscription on it confirms, Archela Priyensky. And on this relief, and on the statues of the last half of the period under consideration, the signatures of their performers are often found, and the artists now excise their name mostly not at the foot of the works, as they did before, but on the works themselves, hoping to better ensure the memory of themselves. We find such signatures on the sculptures of Asia Minor. On the famous “Borghese fighter” of the Louvre Museum, the name of Agassius of Ephesus , who owns this statue, is displayed on a tree stump under the right thigh of the figure (fig. 453). This marble statue, depicting a young, beardless naked athlete, was named after the name Borghese, to which it once belonged.

The courage and vitality of this young man of the offensive movement created the glory of this one of the most expressive marble statues in the world. The young man fights, apparently, with the rider. He takes a big step, leaning forward with his whole body and holding a shield in his left hand.

His right hand, armed with a sword, leaned back in a strong swing. In none of the other statues can one find such a distinctly expressed supreme tension of forces. The realism of this figure indicates that it is executed later on the Pergamon frieze. We can not imagine that it was carved before 100 BC. e.

Fig. 454. Venus de Milo. From the photo

By this time we, along with Furtwengler, carry another famous marble statue - the Venus de Milo, the Louvre Museum (Fig. 454). In the XIX century, she became a common pet due to the beauty of her figure, which unfortunately reached us without hands; the warmth of the heart, which breathes the noble features of her face; the extraordinary softness of cutting marble, giving its nude torso a natural fullness and tenderness. The statue was found on the island of Milos in 1820. It was made, as can be seen from the inscription on a broken piece of the socle, which is one with her, Alexander (or Agesander), the son of Menid from Antioch on Meander. The left leg of the "Venus de Milo" in its present form is on an elevation and, in all likelihood, in fact was somewhat extended above the plinth; now it is filled with plaster. The lower part of the statue is covered with a rather simply laid drapery, which, no doubt, would have gone down if it had not been held by its right hand goddess. Many attempts have been made to restore this wonderful figure. Dedicated to her works would constitute a multi-volume library. The assumption that the god of war stood near her, on the right, is now unfounded. In general, the question whether the fragments of the left hand found near it belonged to this statue as well as the hand with an apple in it belonged to the statue. The opinion that this hand is real finds itself more and more adherents, but there is a fair doubt as to the authenticity of the hand in view of the weakness of its execution. We would have gone too far if we had embarked on a close examination of all attempts to restore this statue. None of them seems convincing to us, nor even the most reasonable attempt by Furtwangler. In his opinion, the left hand holding the apple rested on the stand, while the right one held the drape. The best we can do is to admire the pure beauty of the surviving main parts of the statue of the goddess of Milos. The artistic and historical significance of this statue, according to Furtwengler, is mainly due to the fact that the sculptor, creating it, reworked in the Hellenistic spirit one of Skopasz’s works, which served as a model not only for her, but also for Venus Kapuan’s (see fig. 409). "Venus de Milo," as the ideal image of the deity of Asia Minor Hellenism, refers to the same kind of avatars as the figures of the gods in the Pergamon "battle with the giants." The same must be said about the torso of Apollo, found in the Asia Minor city of Tralles Humane and stored in the Museum of Constantinople. As in the "Venus de Milo" we recognize the alteration of one of the works of Scopas, so the "Apollo Tralless" should be considered for processing one of the types of Praxiteles.

Fig. 455. Farnese bull. From the photo

All the Asia Minor art of the considered pore and earlier time is reflected in small Mirinian terracotta groups and figures that can be seen, for example, in the Louvre Museum. Compared with the Tanagra figurines (see fig. 421), which they resemble, they breathe a more intense life, attached to them in part by eastern ideas.

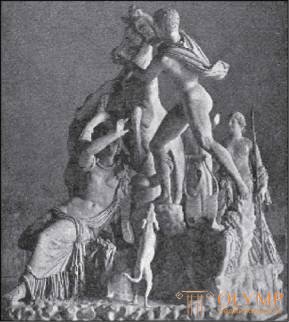

Later Masters of Trallesse introduced us into the realm of tragic plots. Apollonius and Tavrisk composed for the island of Rhodes, and perhaps performed on it, a monumental marble group, already in the time of Pliny the Elder, transported to Rome, where it was discovered near the term of Caracalla in the 16th century, under Pope Paul III (Farnese). Now this group with figures in size, known as the Farnese Bull, is one of the most famous sculptures of the Neapolitan Museum. The plot of this group is taken from "Antiope" Euripides. It depicts the moment when Tsef and Amphion, intending to avenge the insult inflicted on their mother Antiope Dirkei, is tied with a rope to the horns of a wild bull, in order to execute a painful death. Both brothers, standing on the cliffs of Kiferon, restrain the bull, torn from their hands; Amphion keeps him by the horns and by the face; Cef in one hand holds a rope already tied to the horns of a bull, and the other probably grabbed Dirkey’s hair, which fell in horror to the ground at his feet, and tied it to the bull for them. The restoration of this work, in which Cef holds the rope with both hands, is apparently wrong. Antiope stands behind the bull and calmly looks at what is happening. In front sits a shepherd boy on a rock.

A dog with a barking rushes at the bull. The power of the movement and the fever of passion are expressed in the group surprisingly truly. Welker successfully refuted the point of view of the detractors of the Farnez Bull. Of course, in the works of art of the preceding centuries, for which it would be impossible to create such a work, one can see more mature and noble art, but one cannot but admit that it was freedom that prevailed over the art of all other nations in Greek art. performance was finally to produce such works in which the art in relation to technology becomes almost a focus, and in terms of the internal content comes to all sensations in extreme degree of tension.

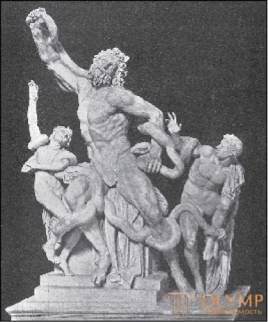

Fig. 456. Laocoon. From the photo

A confirmation of this development of Greek art is also the famous Laocoon group, the Vatican Museum in Rome (Fig. 456). This work, like the Farnese Bull, was known to Pliny the Elder; it stood in his time in the palace of Emperor Titus. The performers of the group, who worked on it in cooperation, Pliny called the Rhodian artists Agesandre, Atenodor and Polydor. What an active part in the development of the arts of that time was Rhodes, can be seen from the fact that, according to the testimony of ancient writers, besides the famous Colossus, the work of the aforementioned Hares, educated by Lysippos, there were up to one hundred other huge statues on this island. The sculptors Agesandre, Atenodor and Polydor are known to us, moreover, by inscriptions on works that have been lost. The nature of these inscriptions, as shown by studies of Hiller von Gertringen, indicates that they relate to the first half of the 1st century BC. e. The opinion that the "Laocoona" group was executed only in the time of Titus, has been very convincingly refuted by Overbek. In any case, “Laocoon” of later origin than the Pergamon frieze with a “battle with giants”, but performed earlier than the Roman poet Virgil lived, since this group has nothing to do with his description of the incident depicted in it. It owes its origin most likely to the Greek tragedy. Laocoon, the Trojan priest of Apollo, was guilty before the gods, for which an angry Athena sent him to punish two giant snakes, who wrapped their father and his children around their rings and strangled them. The group that came to us, which was discovered in 1506 near the term of Titus, as can be seen from everything, is exactly the original about which Pliny the Elder wrote. It represents a catastrophe at its most pathetic moment. Snakes are already wrapped around their victims. Laocoon himself writhes on an altar, and the terrible pain of a snake bite in his left thigh causes him to let out loud cries. Montorsoli, who replenished this group in such a way that Laocoon, holding his right hand high, tries to distract the snake from himself, mistaken: Laocoon’s right arm, convulsively bent at the elbow, is thrown back behind the back of his head (Fig. 457). The younger son sat down on the altar to the right of his father; the second snake dug into his right side, and he was already falling, losing consciousness. The eldest son, standing to the left of his father, at the steps of the altar, is still only slightly wrapped in rings of the monster. He still has enough strength to fight them; with the manifestation of filial pity, he turns to his father. The despair of a terrible moment, expressed in this group with extraordinary force, excites in us "horror and sympathy." Laocoön is especially magnificent. The understanding with which the play of the muscles of his naked strong body, which came into convulsive tension, and the expression of pain in the noble features of his face, framed with a thick beard and curly hair, are evidence of the high level on which the sculpture was. Pliny called "Laocoon" "a work that surpasses everything created by painting and plastic." In the XVIII century, when only a few real Greek works were known, causing our surprise, this group was considered the main creation of Greek art. Now we know that, by its amazing technique, the strength of realism and physical pathos, the Laocoon group at least represents the highest degree of development of that Hellenistic direction that had never tried to reproduce anything taken from real life. We know those prototypes that served as models for Rhodes artists; we recognize, no matter how challenged our opinion on this subject, in the figure of Laocoon

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)