In Northern Syria, we find primitive original culture and art, which with the help of figurative writing and on the basis of common stylistic features can be traced from the north to the borders of Lesser Armenia, from the west to the heart of Asia Minor and to the Ionic shores of the Mediterranean Sea, Apparently, in Asia Minor. Even Wright and A. Says, and especially Perrot and Shipie, defended the opinion that the carriers of this culture and art were the Hittites (Hittites, Gefits), whom in the XIV century. BC e. they had to wage heavy wars with the Egyptians and who were known also to the Jews and the Assyrians. Puchstein doubted this and offered to name the carriers of this culture pseudo-libetta. But since the time of P. Jensen, who first dismantled the letters of this nation and proved that he is the ancestor of the current Aryan Armenians, who called themselves Gatians, one can hardly doubt that "the well-known name of the Hittites" Hittites "corresponds to the name" Gatians "." Anyway, we are talking about the art of those Hittites, whose writings, according to Jensen, were in use between 1300-550. BC e. The ruins of works of Hittite architecture, consisting of walls often cyclopean masonry, indicate the disappeared power and splendor. Products of applied art, among which amulets deserve attention, promise to lead to unexpected conclusions in the future. Until now, the value of the Hittites in the history of art is based only on the monumental works of their sculpture. The remains of large sculptures are found only in a limited number; more often there are figures of lions, the front of which is sculpted completely round, the rest of the body is filled with relief. But most importantly, Hittite plastic works of semi-exalted work, especially those that adorned the gates of the city walls or were carved on rocks in sacred or memorable places. The fact that all these monuments belonged to the same art, which Perrot and his English predecessors vigorously defended, and Gustav Hirschfeld, whom Puchstein again defended and finally proved Jensen, refuted, is manifested in the uniform and uniform development of the costume of the depicted figures. First, the bezborodnye kings of the Hittites wear a high pointed hat, a short sweatshirt and shoes with long toes, as we see in all the monuments of this people. Subsequently, the peaked cap becomes an accessory of the gods, the kings are content with a flat cap and are depicted in longer mantles; then a thick beard gradually appears and, finally, the clothes approach Assyrian.

Regarding the chronology of these sculptures, we mainly use the research of P. Jensen.

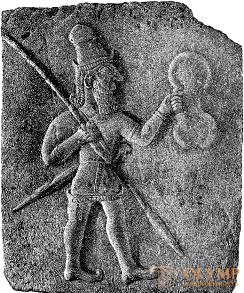

Two reliefs on the rocks of Karabeli, near Nymph, in Lydia, date back to the end of the 2nd millennium BC. e. They depict individual male figures, of which only one is well preserved. Whether these are really the figures that Herodotus considered the Egyptian monuments of the victories of Sezestris is an unresolved question. In any case, there is nothing Egyptian in them, but there is nothing Assyrian either. The best-preserved figure in a pointed hat, in shoes with long socks, with a spear and a bow, by its squat and angularity is characteristic of ancient Soviet art.

Probably a fairly close resemblance to these reliefs has a remarkable Eflathunbunar monument in Lycaonia. Its deaf cuboid facade is surmounted by a monolithic slab, which depicts a solar disk with huge wings extending over the entire monument. On separate fields are presented in two rows, one above the other, partly under the winged sun discs of smaller sizes, now weathered figures with raised hands. The arms, heads, and upper parts of the body are depicted en face, and the legs are in profile. The antiquity of this fantastic work is striking in the same way as its Hittite character.

Around 850 BC e. Reliefs of the palace in Gyudzhuk (Eyek) in Cappadocia. Along its facade, to the right and left of the entrance, stone reliefs depicting ceremonial rites stretch on the basement. There is a worship of the bull. The deity stands on the two-headed eagle, the most ancient of all known. The art of the Hittites seems to be more free and mature here than in previous monuments. Extremely vital animals (oxen, sheep, lions); especially the heads of the lions are remarkable; Two sphinxes at the gate have the appearance of Egyptian figures in Assyrian taste; otherwise assyrian influence imperceptibly.

Fig. 226. Hittite relief from Shinshirely. From the photo

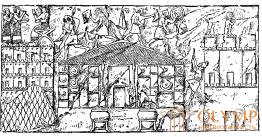

The younger names on the cliffs in the large open sanctuary (Jasilikaya) of Bogazkoye, in Cappadocia, are a bit younger than the Gujukiuk reliefs. And here the language of forms is still rather free of Assyrian phrases; but in their content, these sculptures obviously fit the Syrian and already Assyrian ideas about the deity. Similar to the Malta reliefs described above (cf. Fig. 183), they lead us to heaven, the gods of which stand on animals. To these gods are moving long processions of lower gods, among whom the king marches; ceremonies and individual figures are depicted in various places of the rock. The priest bears, as it were, a small temple, crowned with a winged solar disk and supported by grooved columns, the volutes of which are bent downwards. In these columns, it was thought to see the pioneers of the Ionic columns, but Jensen proved that here, as in the groups of signs found in other places, we see only Hittite hieroglyphs relating to the carrier figure, the king.

The development of the art of the Hittites in all their field, apparently, went the same way. The direction, in which the Assyrian influence was generally imperceptible, was followed by another, perceiving the idea, but not yet the language of the forms of Assyria, and, finally, the third, which was no longer able to get rid of Assyrian forms. Then the art of the Hittites, as old as the weak, quickly submitted to the early Greek spirit, which had burst into them from the west; It itself was too powerless and unstable to play any significant mediating role between the arts of the East and the West.

The region of present-day Armenia, in the northeast of Asia Minor, as established by V. Belkom and Lehmann, occupied in 600 BC. e. and later the Chalds, who owned pre-Armenian wedge-shaped inscriptions. Regarding the works of their art in Van and its environs, there are few positive data in general. Apparently, their stone constructions were as alien as the artistically developed system of columns. The supports of the beams were round pillars without bases and capitals.

Somewhat earlier and at the same time with the art of the Hittites in the north and west of the peninsula, washed by the Black, Aegean and Mediterranean seas, other Asia Minor art flourished, richer in the beginnings of development; The creators of this art, which undoubtedly belonged to the Aryan tribe, were of the same root as the Hellenes, and from the earliest times were in a wide variety of relationships with them. But before the development of this art was over, the entire western coast of Asia Minor went to the Ionian Hellenes, who planted on it or opposed the present early Greek culture to their relative Greek life.

On the threshold of Asia Minor art is a huge work of sculpture, which the ancient Greeks considered one of the wonders of art, if not nature itself: in a niche carved into a rock on the northern slope of Sipila and 10 meters in height, a round figure of a woman on a throne is carved out of natural rock which was previously mistaken for Niobe, sung by Homer, and now is recognized as the depiction of the mother of gods, Cybele, described by Pausanias. According to Pausanias, this statue is made by the son of Tantalus. Consequently, being in a locality that later became part of the Lydian kingdom, it belongs to the fabulous Phrygia Tantalus and Pelops, considered the ancestors of the Mycenaean king Agamemnon. Thus, the Mycenaean art of Troy was also Old Frigian; indeed, the tomb located near Sipil and associated with the name Tantalus, despite some differences, can be likened to the domed tombs of Mycenae. Outside, it is a circular cylindrical structure, folded smoothly from polygonal stones with a conical top, topped with a statue of the symbol of life (phallus). Inside it has an arrow-shaped arch, formed by protruding one above the other horizontal rows of stones, and represents a deaf rectangular chamber with the correct ratio of individual parts. The cone of this tomb collapsed just like the tops of all the neighboring tombs. Symbolic images, sculpted from red trachyte, which crowned him, are scattered around.

Other works of art of Asia Minor belong to the aftermath of the times; therefore, the oldest of them belong to the end of the ninth century BC. e.

In Lydia, from the beginning of VII. (from 694 g.) Gigues, Ardis, Aliatt and Creuse reigned one after the other, first of all, the most ancient burial mounds are interesting. Over the entire field occupied by these barrows near Sarda, stands Aliatta's gravestone, according to Herodotus, not inferior to the Egyptian pyramids. If this tomb did not reach the height of the greatest of them, then it surpassed it in its volume. In this earthen embankment, partly covered with stonework, of which only scant traces remained, hid a rectangular chamber with a flat ceiling made of long marble blocks, and a passage to it, covered though with a rough, but regular-round duct vault. In the history of trade relations, as well as in the history of applied art, the Lydian kings immortalized themselves by inventing and distributing coins. The oldest coins of the times of Giges and Ardis were knocked out of an electron, an alloy of gold and silver, had an ovoid shape and only on one side were provided with in-depth symbolic images, among which a fox occupied a prominent place. It is believed that the improvement, which consisted in the fact that they were minted from pure gold, and made images on them, at least on the one hand, convex, came here, probably from neighboring Ionic cities, Miletus and Ephesus, in Sardis it found imitation even under Aliatte and Creuse. In fig. 227 is one of these ancient Lydian coins with an in-depth depiction of a fox (British Museum).

Fig. 227. Lydian coin. By Perrot and Shipie

More important than the burial mounds of Lydia, along with which you can put the graves of Caria and Mizii (Troy), the tombs in the rocks in the eastern countries of Asia Minor, which differ sharply from the works of Hittite art. It is very important that both kinds of monuments of Asia Minor art, simultaneously appearing side by side with one another, almost exclude one another in their distribution. Tombs in the rocks in the north of Asia Minor are found in Paphlagonia, in the south of the peninsula - in Lycia, and within the country - in Phrygia, in the later post-Hungarian Phrygia, Phrygia of the time of King Midas.

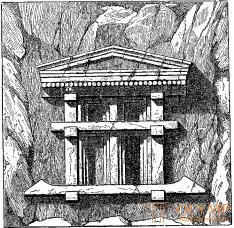

Fig. 228. Assyrian relief depicting an ancient Armenian temple with a pediment. By Botte

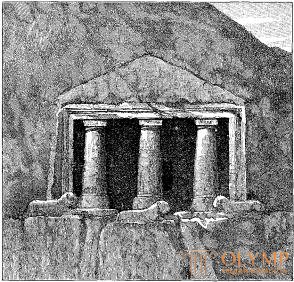

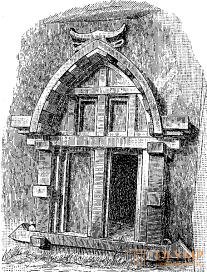

Fig. 229. Midas' tomb in Phrygia. By Perrot and Shipie

Phrygian facades, carved into the rocks, are scattered near Kütagija (Kjutahijas) in a space of 40 kilometers from north-east to south-west. The northeastern ancient settlement of the facades in the cliffs of this area is known from the time of the Texier travels, while the southwestern tombs near Ayazinn were discovered only in the 80s of the 19th century. Ramsay. Then Reber and Kurte again investigated the Phrygian monuments in the rocks; One of the results of these studies, especially those produced by Kurt, is that it should not mix facades of religious significance with grave facades. The Midas Tomb (fig. 229) and all its facades, ornamented with a geometric pattern, should not be considered tombs, since they don’t have a burial chamber, but deceased religious buildings and monuments. In any case, the tomb of Midas, as can be seen from the inscription in the Phrygian language, borrowed from the Phoenician alphabet, is dedicated to or built for King Midas. The imitation of a wooden structure was expressed here in a fake door, leading only to a flat niche in the hem, framing the facade, and also in the shape of a pediment. In addition, the pattern design itself, not quite similar to the meander, but consisting of crosses, squares and quadrangular loops and covering the entire facade, could just as easily be borrowed from similar woodcarving ornaments and patterns on carpets, as is usually claimed. The imitation of a wooden roof can be seen even more clearly in the facade of the Delikli Tash. The monument in the rock near Arslankaya also belongs to the most important works of this genus. It is processed on three sides; on the pediment of its front side there is a sphinx, on the pediment of one of the lateral sides there is a neck, and on the other side there is a lion who has risen on its hind legs; in the niche is an image of the great mother of the gods with two lions on the sides. This building can certainly be considered religious. From all its ornamentation, although of local origin, the Greek spirit already blows; the same can be said about the frieze of palmettes and buds on the facade in Kyuchuk-Yasili-Kaye, in which its Assyrian origin was expressed as clearly as the Ionic character.

Figure 230. Mountain tomb in the Gambarkaya. By girshfeld

Наоборот, в так называемом юго-западном некрополе встречаются настоящие гробничные фасады. Подражание жилью обнаруживается у них не столько снаружи, сколько внутри. В погребальном покое, как правило, вырубаются ложе и при нем каменное изголовье. Одна из самых любопытных усыпальниц – так называемая "развалившаяся гробница", фасад которой украшен довольно хорошо изваянными львами и двумя воинами в латах, сражающимися с чудовищем. Вышеупомянутые фасады с геометрической орнаментацией едва ли древнее всех других, как это полагали до сего времени. Переходным звеном является именно памятник в Арсланкайе. Из всех этих произведений, по-видимому, ни одно нельзя отнести к более раннему времени, чем VII в. BC э., и едва ли какое-либо из них исполнено раньше разгрома Лидийского царства персидским царем (546 г. до н. э.). В той же местности находится еще вторая, более поздняя серия гробниц в скалах с фасадами совершенно эллинского характера. До сих пор полагали, что происхождение их относится к V и IV столетиям до н. e. Однако Кёрте и Ребер доказали, что они принадлежат эпохе римских императоров. Лишь одна из них могла бы быть приписана промежуточной эпохе, именно гробница, открытая Кёрте близ Кёкче-Киссика: по гладкому фасаду с фронтоном и по колоннам открытой галлереи она подходит ближе к пафлагонским гробницам в скалах, чем к более древним, фригийским.

These paflagon tombs in the rocks, explored by Gustav Hirschfeld and partly open to them, are distinguished by a semi-Greek style and burial chambers with open aisles to them, as well as porticos on the columns, this is not typical of Phrygia buildings. The portico in front of the tomb in Gambarkaya (Fig. 230) has three columns, many of the porticoes in Iskeleb - two, and one of them is the only column. Columns taper upward, rest on massive footings and, instead of capitals, are equipped with quadrangular plates and sometimes several plates lying one on another. Only the capitals of the columns of the fourth tomb in Iskelib, consisting of lion heads, are somewhat different.

Fig. 231. Lycian Mountain Tomb: triangular pediment. According to Texier

Lycian tombs in the rocks, thoroughly researched and described by Benndorf, are distinguished by the imitation of wooden buildings. Although none of them are older than the tombs of the Persians, many are younger than the conquest of Lycia by the Macedonians, and some are close to the buildings and sculptures of the Greek style, but in their type they belong, obviously, to the pre-Greek period, and since nothing like them is found anywhere, should be considered their national Lycian monuments. These stone facades of tombs and burial buildings of Lykia are exact replicas of local wooden log buildings. They can clearly distinguish thresholds, pillars, frames, beams. The ends of the beams strongly protrude outward and sometimes hook-shaped.

Fig. 232. Lycian mountain tomb with a lancet pediment. According to Benndorf and Reiss

Hellenic art will lead us once more to Asia Minor. The borrowings made by him at the time of his infancy from the Asia Minor barbarians, it returned to them in abundance. But it would be a mistake to attribute the period of Greece’s influence on non-Greek Asia Minor to the early epoch and see in the above-mentioned Paflagón and Phrygian capitals of the columns resembling the Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian Capitals of the Greeks, no more than miserable imitations of Greek patterns. The very diversity of their outlines, fresh and original, proves that they, like the Cypriot capitals, are likely to be considered the initial forms of the developed Greek orders, although in some cases they are younger than the latter. Only due to the interaction of these and similar previous stages on the same soil of local development and eastern influence, the high artistic imagination of the Greeks managed to develop their three classical orders.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)