Ludwig Siebel calls the period of the New Kingdom "the epoch of world relations". Then the Babylonian state flourished, although it was during this period that we know him least of all; at that time, a peculiar culture existed in Syria, Palestine, Phenicia and Asia Minor, and on the soil of Greece, education dominated in the poems of Homer, which is commonly called Mycenaean. Relations between all these countries were committed through peaceful exchanges and hostile clashes. Tutmes I, the pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, in a victorious procession reached the Negro countries of Nubia and the shores of the Euphrates, Tutmes III, with his campaigns in Syria and Palestine, approved the predominance of Egypt in that era of world history. The 19th dynasty includes the long and victorious wars of Set I and the great Ramses II with Hethe, the Mer-fta wars with the Libyans and the peoples of the Mediterranean coast. Under Ramses III, the 20th dynasty, uncountable hordes, advancing from the north, struck the stronghold that was the Egyptian kingdom. But the period of time, from Ramses IV to Ramses XII, was an epoch of decline, from which Egypt recovered only a few centuries later.

Fig. 126. Part of the gold dress princess Gator-Sat. From the photo of Brugsch

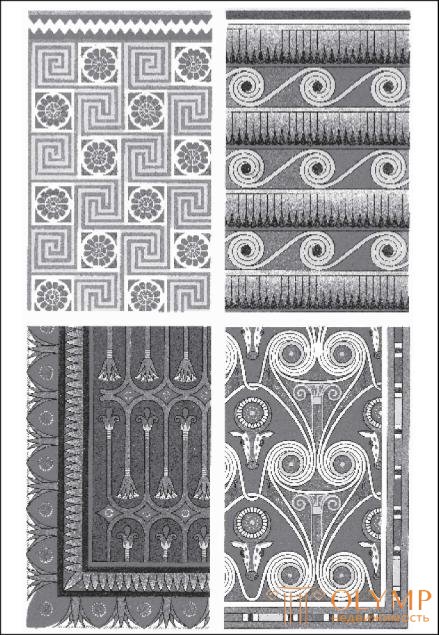

The Pharaohs of the New Kingdom, perhaps, greater builders than generals, covered the Nile Valley with a multitude of gigantic structures, the remains of which even now, 3,500 years later, retain the imprint of that era; they decorated the walls of their palaces, temples and tombs outside and inside with colorful reliefs or paintings that occupied the most vast spaces that had been allotted to it from other peoples; they supplied their above-ground and underground structures with statues, the colossality of which is a symbol of spiritual power. How much the world affairs of the Nile Valley have influenced Egyptian art remains unclear. True, numerous fragments of Mycenaean vases in Egyptian tombs, images of prisoners belonging to foreign races, and treasures of ambassadors who are tribute on flat images of Egypt, found in Tell el-Amarna wedge-shaped inscriptions in Babylonian language, inscribed on clay plates and containing in itself, the messages of the Asian kings and Egyptian governors to Pharaoh Amenophis IV (Berlin Museum) testify to how great the international relations of the Egyptians of that time were. It was at this time in the Egyptian ornamentation, especially in the picturesque decorations of the tombs, a number of new motifs appear, such as, for example, a system of spirals with a wedge-shaped calyx, a band studded with rosettes, or a developed network of quatrefoil and a combination of various kinds of cups with a lotus flowers or papyrus - a combination that, despite the purely Egyptian character of its constituent elements, is mistakenly called “Phoenician bouquet” or “Syrian flowers”; Richl called this ornament an Egyptian palm tree, and Borchardt called the “bouquet column”. It is impossible to deny that all these motifs are repeated in works of art and Central Asia, and Mycenaean, but it is hardly possible, together with some researchers of Egypt, to look at them as borrowing from the outside, and not as original Egyptian phenomena repeated by other nations. We find the spirals even during the first dynasties, and the opposition of the spirals is found on the scarabs of the 12th dynasty; "Syrian flower", that is, Egyptian palm tree, is found in Egyptian tombs much earlier than in the monuments of Syrian and Cypriot art; Finally, we, together with Richl, consider it a priori incredible, so that people endowed with such self-consciousness and such ingenuity as the Egyptians could suddenly lose their strength for further independent development. In any case, to speak of the "influx of elements of Asian culture and Asian art", which flooded Egypt, it would mean to go too far.

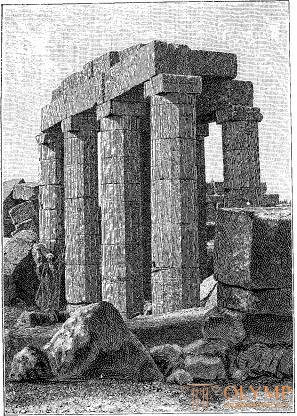

The architecture of the New Kingdom, the center of which was the "hundredth" Thebes, we can study mainly in the temples. But it should be distinguished temples, built in the open areas of the Nile Valley, from the temples in the rocks or grottoes of the upper part of this valley, constrained by cliffs. Then it is necessary to distinguish from the huge main temples, the architectural charm of which lies mainly in their insides, small chapels, colonnades and galleries of which are turned outwards. Next, it is necessary to distinguish the temples designated for worship from the temples in honor of the dead kings, which at that time were often built at a considerable distance from the tombs of the pharaohs. The tombs of that time, settled exclusively in the rocks, although often reaching enormous sizes, from an artistic point of view are of interest only from the painting that adorns their interior.

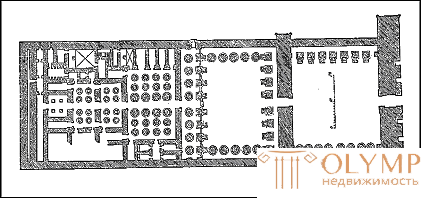

Fig. 127. Plan a gravestone temple of Ramses III in Medinet-Abu. By Perrot and Shipie

The most necessary for the cult, but the least interesting from the artistic point of view, was a low dark hall of the sanctuary. Surrounded by various chambers designed for the needs of worship, he was the final room in the whole enfilade of courtyards and halls leading to it. The location of these courtyards and halls was designated even outside the building itself, in its sacred fence. The road to the entrance, on the sides of which two massive obelisks stood guard, was between two rows of sphinxes facing each other with human or sheep heads or rams. The entrance gates, topped with a grooved cornice with a winged solar disk sculpture in the middle, seemed low, as if crushed between massive towers, the so-called pylons, which occupied the entire front facade of the building (see Fig. 97) and were also fitted with a grooved eaves and rings in which poles with flags were inserted. On both sides of the entrance gates colossal statues of Pharaoh, the founder of the temple, rose. Having passed the gate, the visitor entered, first of all, into the open courtyard, surrounded by a colonnade, into the so-called peristyle. Here, but not further, the people were allowed to take part in solemn sacrifices. This courtyard was followed by a pillared hall (hypostyle hall), the most artistic part of the Egyptian temple; its middle nave, the ceiling of which rested on higher and massive columns than the columns of the side aisles, had openings for the passage of light in the upper part of its walls, which surpassed all the rest of the structure. From this hall a special passage, also often decorated with columns, led to the lower room of the sanctuary. All these parts of the building, which the builder could optionally increase in relation to both the number and size, were designated outside in the dismemberment of the inclined walls characteristic of Egyptian architecture: on the edges of these walls was that roller, and at the top of them was the eaves with which we already met above; the ceilings of the above premises were stone, flat.

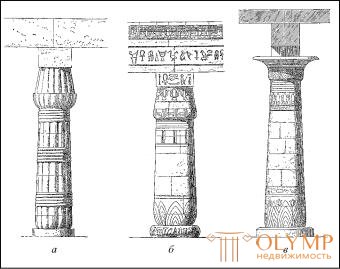

Fig. 128. The development of Egyptian columns in the era of the New Kingdom. By Perrot and Shipie

The change in style was expressed primarily in the form of columns (Fig. 128, a, b, c, and Fig. 129, a and b). The column with a capital in the form of an unblown lotus flower, this pride of the Middle Kingdom, disappears. Columns with a capital in the form of an unfolded flower, often representing the now pointed petals of the calyx of the plant Nymphaea caerulea, are found, like lily-shaped columns, only in the figures. Papyrus columns with capitals in the form of a closed bunch of flowers of this plant gradually lose their characteristic features. Sometimes the column is composed of many stems, intercepted in several places like hoops (Fig. 128, a). But more often, both the column itself and its capital are divided into eight stems (Fig. 128, b). Columns in the form of bundles of stems after the 19th dynasty are rare. A papyrus column with a smooth stem and a capitol in the form of an open bunch of flowers (Fig. 128, c, formerly called the capitol as an open lotus flower) comes to the fore, and it can still be distinguished by the narrowing of the base and short leaves on the bottom and on capitals, which are found only in papyrus. Palm-shaped columns are becoming more common, and the bell-shaped capital, which originates, in all likelihood, from the capitals of wooden poles for tents (see fig. 112, e), makes weak attempts to perform on the stage at Karnak. Smooth rods of columns are covered with inscriptions and drawings, and all the walls of temples, like columns, are also abundantly decorated with letters and images that differ in more magnificent and more varied tones of colors than the paintings of previous times. "The temple," said Maspero, "is an image of the universe, as the Egyptians understood it. Each part of it was decorated according to its meaning." The base of the walls is decorated with all kinds of floral ornaments. The blue ceiling is littered with yellow five-pointed stars. Between them, the kites of the goddesses of the south and north are hovering, occurring both on the ceiling of the middle nave of the hypostyle hall and on the door linens; sometimes the sun and the moon are depicted on a dark as night background. But among the earthly flowers and the heavenly bodies that adorn the inner walls of courtyards and halls, as well as the outer walls of pylons, there are true paintings. On the outer walls and partly on the walls of the courtyards enclosed by columns, the king's worldly deeds are depicted, his wars and victories are glorified. Then, going deep into the temple, one can see how the king, surrounded by members of his last name, approaches the deity, its ancestor. Finally, on the walls inside the temple, godly acts and sacrifices that were once committed by the king are depicted.

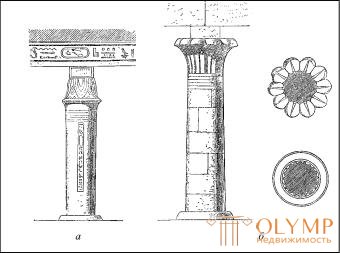

Fig. 129. Columns: a - with a bell-shaped capital, at Karnak; b - with a palm-shaped capital, in Solele. By Perrot and Shipie

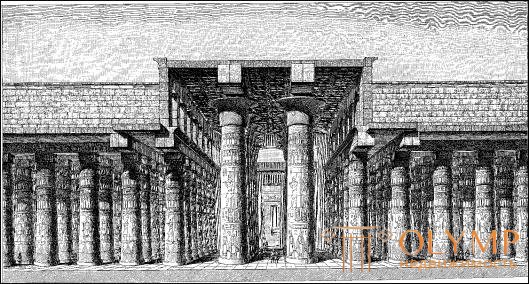

From an architectural point of view, the Egyptian temple can be considered the first attempt to create a dissected stone structure, expressing the inner content in its form. But this attempt was not always crowned with success. So, for example, a hypostyle hall divided by columns into several naves, having a flat ceiling and illuminated with windows done in the upper part of the walls of the highest middle nave, was in essence a solution of the problem naturally associated with the size of the hall and, moreover, a solution that opened the way to the success of the building art. However, the separate premises of the Egyptian temple did not constitute one organically integral structure; the artistic decoration of the columns deprived them of the impression of strong supports, and the whole building was generally ponderous, the weight was felt from the outside even more than the inside because of the massive walls divided into parts and the towers at the entrance gates. But even inside the building, the overall impression was rather oppressive than elevating spirit, because the visitor had to wander in the gloom of the forest of columns, between their thick trunks, close to each other, and, as they approach the sanctuary, plunge into the darkness more and more thick, unenlightened. At least outside, while it was light, paintings and inscriptions took over. Located in a strictly defined system, they played the role of interpreters of the idea of both the spiritual and artistic significance of the entire structure.

Fig. 131. Hypostyle hall in the Karnak temple. On the restoration of Shipie

Fig. 130. A group of columns of the temple of Amon at Karnak. With photos Plyushova

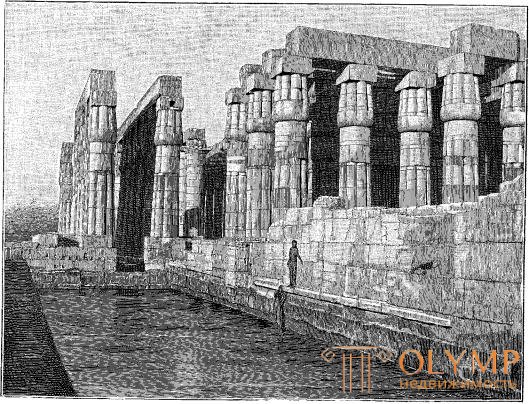

As mentioned above, the center of the construction activities of the New Kingdom was Thebes. The villages of Karnak and Luxor are located on the right bank of the Nile on the site of the ancient city. The construction of the great Karnak temple of Amon, founded by Amenemhet I, the pharaoh of the 12th dynasty, was continued by almost all the sovereigns of the 18th and 19th dynasties and even later times. The temple, preserved in Luxor, which was preceded by an unfinished building belonging to the Middle Kingdom, was begun by Amenophis III, the pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, and completed by Ramses III, the 19th dynasty. The large temple of Amun at Karnak, 1400 meters long and 600 meters wide, is the largest monument of Egyptian religious architecture (Fig. 130). In its main hall, built by Tutmes III, there are also protodoric columns (see Fig. 121), which are like copies from the Benihassan columns. In the peristyle of the courtyard, belonging to the same king, there are eight-column papyrus columns with closed flower umbrellas and sharp edges of the stems, which we have already pointed out (see Fig. 101); in one of the other galleries of the same temple, the columns have a capital in the form of a bell, which faces a hole downwards (cf. fig. 129, a); a capital in the form of an umbrella of flowers, open from above, appears for the first time inside this temple only in a large hypostyle hall belonging to the 19th dynasty; of 134 columns on which the ceiling of the hall, which is 100 meters long and 50 meters wide, rests, such a capital is given to only twelve round smooth columns of the middle nave, reaching 21 meters in height (fig. 131). In the large temple of Luxor, the front courtyard of which lies at an angle to the rest of the more ancient part of the building, the capitals in the form of an umbrella of flowers are found in a high 14-column passage connecting this first courtyard to the second. In general, even in Luxor, a closed papyrus capital predominates, but not in a smoothed form, but in the form of a bundle. The core of the column is sometimes intercepted in various places by large hoops (Fig. 132). In Thebes, on the left bank of the Nile, mainly the great funerary temples of the 19th and 20th dynasties deserve attention. Back in the 1st c. The queen of the 18th dynasty, Hatshepsut, daughter of Tutmes I, built in Deir el-Bahri, near Thebes, for herself and her loved ones a wonderful structure deserving the same attention as half-cave temples among the tomb temples of the kings. The temple’s sanctuary itself is carved into the rock. Four courtyards, arranged by columns, through which the cave temple passes, lie one above the other on four terraces, connected by stairs. Anyone who sees the influence of Asian structures in the form of terraces, with which Tutmes I could get acquainted with his hikes, should recall that the buildings of the Egyptians have always adapted to the terrain and that in each of their temple there are small rises with steps leading from one premises to another. The passages to the temple in question are covered with a ceiling, holding onto the stones one above the other. Amenophis III, to whom the main parts of the temples of Karnak and Luxor are attributed, as well as the sitting colossi in Medinet-Abu, which were once in front of his temple, created in the small temple Elephantine, on the southern border of the state, an exemplary structure of a special type of temples, arranged outside with columns from all four sides; unfortunately, this building was destroyed in 1822 and is known only from drawings.

A very special place in the history of both religion and architecture of Egypt is occupied by Amenophis IV. He replaced polytheism with worship only of the sun. He disliked the city of the temples of Amon and founded between Thebes and Memphis, in the current Tell el-Amarne, a new city that adorned the temple of the sun and the palace; their long-known ruins brought a lot of new discoveries, thanks to the research of Flinders Petrie. Already in the pillars of the palace, there is a desire to refresh and revitalize the decrepit Egyptian art with new borrowings from nature. Some of the columns are a bundle of reeds, tied with straps, and images of geese hang under their capitals. Other columns are decorated with tendrils of ivy or cissus leaves copied from nature. The third columns are surrounded by ornamental fields on which spirals appear. Finally, there is a capital palm-tree, as in Soleb around the same epoch, sometimes with a glass mosaic of blue, golden and red. “In general,” said Steindorf, “the preference given to mosaic technology is everywhere. Guski crowning the walls were often lined with pieces of black and red granite; hieroglyphic inscriptions were also composed of dissimilar stones.” Along with the wall painting on plaster there are painted painted floors. The art of Tell el-Amarna is distinguished by a motley, peculiar freshness. But just as soon after the death of Amenophis IV, his religious reforms, under the pressure of a hierarchical reaction, turned into nothing, the peculiar art of Tell el-Amarna crumbled into dust, from which it arose.

Fig. 132. Ruins of Luxor temple. With photos Plyushova

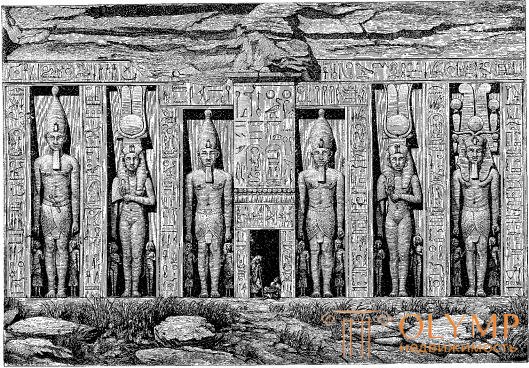

Seth I, the pharaoh of the 19th dynasty, built a temple with palm-shaped columns at Sezebye; но главным его сооружением, которое продолжал его сын и преемник Рамсес II, стал большой храм в Абидосе с его передними дворами без колонн, двумя залами с колоннами, но без среднего нефа, с семью святилищами, крытыми ложными сводами. Преемник этого государя, Рамсес II Великий, покровительствовал зодчеству больше всех других повелителей Египта. Продолжая в Фивах, на правом берегу Нила, постройку Луксорского и Карнакского храмов, он сооружал на левом берегу свой надгробный храм, известный под названием Рамессеума, в котором второй двор украшен столбами с кариатидами. Рамсес II построил храмы также в Мемфисе, Танисе и Бубастисе. Но особенно своеобразны оставшиеся от его времени небольшие храмы, высеченные в скалах по верхнему течению Нила, в Нубии. В Бет-эль-Валли, Герф-Гусене и Вади-Себуа, равно как и в Дейр-эль-Бахри, эти постройки относятся к полугротам, так как их передние помещения расположены под открытым небом. Но в Абу-Симбеле (Ибсамбуле) храмы уже совершенно скрываются в недрах отвесных прибрежных скал, так что снаружи видны только их фасады. Фасад малого храма в Абу-Симбеле украшен стоящими во весь рост колоссальными фигурами, из которых четыре изображают Рамсеса II, а две – его супругу (рис. 133). Внутри храма потолок зала подпирается шестью столбами, на капителях которых снова является голова богини Гатор. Фасад большого храма, столь часто воспроизводимый в рисунках, занят четырьмя сидящими колоссами, достигающими 20 метров высотой; рядом с ними стоят статуи меньших размеров. Потолок первого большого зала внутри храма покоится на восьми так называемых столбах Осириса, то есть на столбах, лицевая сторона которых украшена колоссальными статуями Осириса во весь рост, прислоненными к ним спиной.

Fig. 133. The facade of the small temple of Abu Simbel. According to Priss d'Aveno

However, despite the enormity and magnificence of their works, the architecture of the 19th dynasty with its schematic neatness and smooth lining of the columns presents undoubted signs of the decline of that power and grace that distinguished the architecture of the 18th dynasty.

Of the buildings belonging to the era of the 20th dynasty, only those that were built under Ramses III are remarkable. In Karnak, not far from the large temple of Amon, he built the temple of Hon, the god of the moon, the son of Amon, not distinguished either by size or elegance of details, but often mentioned in the history of art as the simplest example of Egyptian temples architecture (see Fig. 97). The tomb temple of Ramses III in Medinet-Abu is only a riddle from Ramesseum, his great predecessor. On the other hand, a very original civilian structure is the Ramses III Pavilion, richly decorated with flat images and located along one longitudinal axis with a gravestone temple, at some distance from its entrance. This structure, a semi-fortress-half-palace, apparently, can be considered as a monument to the king, invented by him.

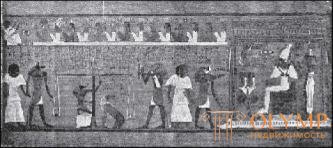

In the flat images on the walls of these buildings, our attention is stopped by more reproduction of the secular acts of the pharaohs than the mystical images of religious rites, scenes of initiations, sacrifices, burial of the departed and transportation of mummies in the burial courts. Only now, in the period of the New Kingdom, images of the trial of the dead with weights for the soul appear, which testifies to the growth and evolution of the Egyptian beliefs. Some of the reliefs of religious content in the temples, such as the image of a goddess who feeds the king with her breast (in Gebel Silsil and Beth Valley), or many images of the praying king (Amenophis III in Thebes and Seth I in Abydos), belong to the most distinctive and gracious fantasy creatures of Egyptian artists. On one relief, located in the Louvre and quite tolerably preserved its colors, Seth I is presented along with the goddess Gator. The relief of the Abydos temple, depicting a sacrifice performed by Pharaoh, already reveals a change in artistic outlook, finally matured in the era of the New Kingdom. The proportions here are slim and stretched much more than in the period of the Middle Kingdom; through thin covers on the lower half of the figure, the body slightly shines through; the desire for lightness is noticeable everywhere, but the traditional position of the upper half of the body is still far from being left, and the thumbs on the right hand and on the left leg are still not drawn on the proper side. During the 19th dynasty, an unnatural way to depict fingers bent outwards is repeated in the future, for example, in the lime relief, depicting Ramses II as a child (Louvre).

Fig. 134. Egyptian ceiling ornaments of the New Kingdom. According to Priss d'Aveno

The real works of historical monumental art should be considered images of the civil acts of the pharaohs on the outer walls of the temples of the 18th and 19th dynasties. The acts of the sovereigns of the 18th dynasty were for the most part peaceful. The picture of Queen Hatshepsut in the country of incense on the Red Sea, depicted in her gravestone in Deir el-Bahri, presents a graphic picture. The procession is still located in several rows, one above the other. Water, indicated, as always, by sheer zigzags, teems with turtles, sea crayfish and all sorts of fish. Scenes of load and departure of ships differ in the greatest movement. Then the novelties of the 19th dynasty are great pictures of the wars of the era of Set I and Ramses II. The defeat of the Bedouins is represented on the outer surface of the walls of the Karnak temple. In Thebesan Ramesseum, in the Luxor temple and in one of the chambers of the Abu Simbel temple, Ramses II is depicted - a giant on a military chariot drawn by ardent horses, pulls a bow or shakes with a spear, he triumphs over his enemies, who lie before him one on another, or attacks the besieged fortress. Ramses III in the temple at Medinet Habu is depicted staring at a naval battle, standing on the shore, firing arrows from his bow and stepping over corpses, as well as returning on chariots from lion hunting in thick reeds. In the images of battles and military expeditions of this epoch there are all those attempts to express distance, to which we indicated above, that is, when depicting figures that are in different planes, one behind the other, they are placed entirely or half one above the other, and the contours are doubled , with the figure that is further, given an even larger size than the nearest. The novelty was also the image of the horse, which generally appeared in Egypt only during the Middle Kingdom. Although the forms of this animal at that time were never developed with such love as in the Old Kingdom, donkey forms, but the movements of horse figures are reproduced vividly and clearly. Gently-felt love scenes on the walls of the pavilion in Medinet-Abu take us to a completely different world. They represent the episodes of the intimate life of Ramses III and his wife. Each of these paintings is a small sweet idyll.

Fig. 135. Amenhotep IV and his spouse. Relief in Tell el Amarna. According to Lepsius

From the images on the plane in the Theban tombs of the New Kingdom, the decorative ornamentation of ceilings is primarily interesting in the decorative aspect. In fig. 134 shows how flower cups of various shapes, Egyptian palmettes, rosettes, curling ribbons and even bull skulls are mixed in this ornamentation with geometric or geometrized basic motifs, including, along with arc coymas, chess fields, etc., also appear networks of meanders and spirals. Wall paintings with figures performed in royal tombs semi-volumetric (previously mostly flat) and introduce us to various ceremonies of religious worship, funerals and trials of the dead, not found in ancient tombs, but mainly with the everyday and home life of the inhabitants of the Nile Valley. In the way of reproduction of plots, we meet here new attempts to discard the ancient Egyptian patterns and introduce new motifs and movements observed in nature into the image. In this regard, the tombs in Tell el-Amarna are particularly significant. Worship of the sun is depicted here with extraordinary clarity. The solar disk stands above the sacred rite in heaven and sends its rays to the earth, from which a hand comes out, ready to accept the sacrificial gifts. Amenhotep IV, called in Tell el-Amarna Juen-eten, and his wife, sitting next to him, are depicted as a single figure with double contours, but with extremely individual, almost caricature features, with an amazingly thin neck, protruding belly and soft rounded lines (Fig. 135). In the feast scenes, the servants are given free poses, and the legs of the figures in Tell el-Amarna more than anywhere else have the correct position to see all five fingers. Finally, painting on the walls and on the floor, opened by Flinders Petrie in the Palace of Tell el-Amarna, is very important. In the middle of the best-preserved floor (fig. 136) there is a pool of water with fish and lotus flowers; in the space surrounding this pool, birds flit over various kinds of flowers. All this together is amazingly free and natural for Egyptian art. But for this reason alone, we still do not consider ourselves entitled, like Gelbing, to ascribe to these images Mycenaean or Phoenician origin. In our opinion, the researcher Shteyndorf exaggerates, arguing that these images are "performed in a completely natural style, free from all conventions." In essence, only a few steps have been taken here to achieve greater naturalness. In the same way, it is necessary to consider an exaggerated opinion, as if in the faces of two princesses in one of the wall paintings "light and shadow are transmitted with an amazing gradation of tones."

Fig. 136. Painted floor in Tell el-Amarna. By Flinders Petrie

But with regard to the freedom of movement of figures, the real paintings in some of the Theban tombs of that era really go farther than what was thought possible in ancient Egyptian art. One has only to look at the dancers and musicians in one Theban painting from the British Museum (Fig. 137), to immediately recognize that the Egyptians were really able to replace the usual profile in the paintings en face and en trois quarts. However, Erman is quite right: such liberties were allowed only when depicting the faces of lower classes; but even then, let us add on our own, these liberties were no more than exceptions, confirming the general rule.

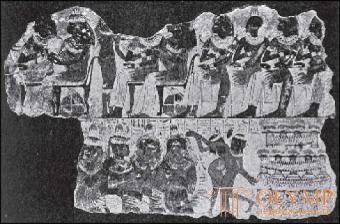

In Egyptian painting of the considered epoch, a special kind of flat images emerges - paintings on papyrus, the world's oldest book illustrations or miniatures. The first papyrus scrolls with similar images refer only to the period of the New Kingdom. The images occupy the upper part of the manuscript, and are located in various places of the text, and are sometimes located all over the scroll. These are red or black contour drawings made with a thin reed pen and then slightly or completely illuminated with a brush. Most of the papyrus scrolls before the Greek era were preserved in the tombs. The sayings, who served the dead, so to speak, a guide to eternal life, were written for the dead: in the Old Kingdom - on sarcophagi, in the Middle - on the coffins, in the New - on the scrolls of the papyrus, placed with the corpse. These scrolls were usually decorated with drawings. Their samples are available in almost all European museums. The oldest of the surviving books of the dead belongs to the 18th dynasty, and the oldest of all "books that exist in the netherworld" - to the 20th. A complete copy of the Book of the Dead is in the Turin Museum. Drawings of such scrolls rarely represent anything new in artistic terms. The main place among them is occupied by images of the trial of the dead. In fig. 138 - a fragment of a papyrus scroll stored in the British Museum. In contrast to such monuments, satirical papyruses introduce us to a new aspect of the character of the Egyptian people and their art. It is based on the love of mockery with the help of an animal epic. The actions of people or of certain persons are transferred to the world of animals and through that they are exhibited in a ridiculous way; for example, the satirical papyrus in the Turin Museum presents a parody of the exploits of Ramses III, depicted in his Pavilion at Medinet Habu. Fighting warriors are presented in the form of cats and rats. On one of the papyri of the British Museum, the king is depicted as a lion, and his wife, with whom he plays chess, is depicted as a gazelle.

Fig. 137. Theban fresco of the New Kingdom era. With a photo of Thompson

Fig. 138. The trial of the deceased. Painting on papyrus. With a photo of Thompson

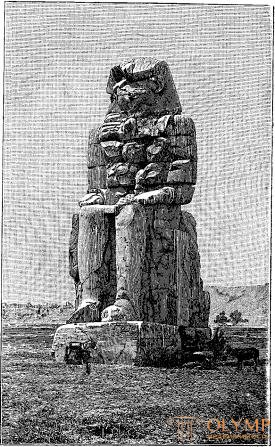

Fig. 139. Statue of Memnon near Medinet-Abu. From the photo

The sculpture of round figures in the era of the New Kingdom, which easily overcame technical difficulties in modeling particulars, especially legs, hats and clothes, was distinguished by even greater thoroughness, but in general was simpler and lifeless than in the Old Kingdom. With the portrait likeness of the sculptures of kings, their faces are embellished according to the prescribed prescriptions; figures are becoming more slender; their posture, as far as the Egyptian numbness permits, is made more and more natural and free. Of the gigantic statues of the kings in a sitting position, carved out of red granite, which were erected in front of the temples, the statues of Amenophis II at Medinet Habu are remarkable, one of which was known to the Greeks as the singing statue of Memnon. They reach a height of almost 16 meters, without a foot (Fig. 139). Colossus Ramses III in the Ramesseum has a height of more than 17 meters. The Colossi of Ramses, who stood in front of the temple in Abu Simbel, as most of the remaining information, which Maspero considers exaggerated, says, reached up to 20 meters high. Of the smaller royal statues belonging to the New Kingdom, the statue of Tutmes III in the Museum of Giza is notable for the naturalness of facial sculpting, just like the heads of Giremgeb, the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, and his spouses kind of animation of very successfully reproduced facial features. The most beautiful of all the numerous statues of Ramses II is considered to be a granite statue in the Turin Museum, excellent in technique and indicating the artist’s observation. Of the other kinds of sculptures, the sessile family groups are particularly interesting, such as, for example, the Pta-Mai group, the priest of Pta, in the Berlin Museum (see Fig. 104), and also the figures of people praying, offering sacrifices or squatting. Squatting figures are usually wrapped in wide mantles. Saint-Mut, the tutor of the princesses at the court of Queen Hatshepsut, whose statue of black granite is in the Berlin Museum, is wrapped in such a robe with the princess (Fig. 140).

Fig. 140. Statue of Saint-Muta. From the photo

The host of Egyptian celestials comes at this time a new deity, the evil spirit of Bes, depicted as a dwarf who grinned his teeth. He is credited with West Asian origins. Since the 18th dynasty, his figure has been repeated countless times, in large and small sizes. The small faience statue of Bes, the Berlin Museum, is reproduced in Fig. 141.

Fig. 141. Bes playing the harp. According to Erman

The oldest surviving Egyptian bronze figurines, such as, for example, the figurines of Ramses II in the Berlin Museum, which can be considered the oldest cast in bronze in the world, also belong to the New Kingdom; but most of these works belong to a later era. Especially famous is the bronze statuette of the Bubast queen Kuromama, the 22nd dynasty, located in the Louvre Museum in Paris. In this figure, the luxurious golden unmasking corresponds to the harmony and roundness of the forms characteristic of the refined taste of the era of its execution (Fig. 142).

Among the clay figures of the New Kingdom, which the masses laid in the tombs with the dead, curious faience figures with colored, mostly blue irrigation. Samples of ivory carving are generally found in separate specimens from the time of the 52nd dynasty; Among the products of this genus, the statuette of Ichi, the 18th dynasty, and the museum in Giza stand out. Iti sits on the cup-shaped capitals of the column and looks at the world imperatively and at the same time comical. Small wooden figurines of the New Kingdom are often struck by the great subtlety of execution. A standing warlord in the Louvre and a similar figure in the Berlin Museum belong to the 18th, and the famous wooden figurines of priests and children in the Turin Museum belong to the 20th dynasties. Carved into the tree are lovely “toilet spoons”, the handles of which represent extremely realistic motifs borrowed from the vegetable kingdom and from the lives of animals and people. The flowers, buds and stalks of the lotus are repeated here in a wide variety of forms. In one of the spoons in the Louvre Museum, the drawing of which is often cited in publications, the handle is a thicket of lotuses through which a notable girl sneaks around, picking flowers, with a highly selected dress (fig. 143). The handle of the other spoon represents an almost nude girl who, while swimming, chases a duck; the spoon itself is hollowed out in the back of the duck. Similar works are in the Museum of Giza.

Fig. 142. Bronze statuette of Queen Kuromama. With photos of Girodon

Products of goldsmiths during the three great Theban dynasties closely adjoin the same works of the Middle Kingdom. The breastplates of mummies, the framing of which depicts the gates of the temple, and the middle is occupied by symbolic, through-work, emblem-style patterns, constitute the main kind of jewelry among the remaining monuments of goldsmiths in the New Kingdom. To the number of Kleynods of the Museum of Giza

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)