Conducting the border between primitive and cultural peoples is a task that can stir up controversy. If someone wanted to recognize for primitive peoples only savages existing in hunting and fishing, and people on the prehistoric steps of the later stone and early metallic eras began to be called semi-cultural, then there would be few objections to this. For us, the point is not in the name, but in the course of development.

In prehistoric Europe, the introduction of metals into use, especially bronze, gave the whole life of the peoples a new, more gratifying, more brilliant character and highlighted a new way of decorating, although in the main branches of art, in architecture, sculpture and painting, a turn towards a better understanding forms and to greater maturity did not occur suddenly, but gradually; thus, the art of primitive peoples who can handle metals, especially iron, for example, the art of African blacks and Malays of Southeast Asia, is far from being in all, although in many respects it rises above the art of primitive peoples unfamiliar with metals.

To Malays, the ability to extract and process metals was brought, probably from the north-west, to blacks, from the north-east; but the acquaintance of both those and others with metals is older than their temporary or local increase over the primitive state. Andrei even considers it possible that the negros themselves have found a way to extract iron, especially since "their country throughout their length gives them good, easily melted material in bog ore." Bronze and brass, in any case, were brought to the Negroes as a gift of foreign lands; However, most of the metal products of those Negro tribes that, in artistic terms, attract our attention, are made of bronze or brass.

Both to the Negroes and the Malays, the ancient, alien and higher cultures were brought long ago. But while the Malays were consistently subordinate to Indian, Arabic and Chinese influences to such an extent that there was almost no trace of their own primitive state, the Negroes, despite the pressure on them of the ancient Egyptians, Arabs and Hindus, so stubbornly held their own characteristics that only in the north of the area they occupied, along with an admixture of foreign blood, an admixture of alien cultural elements occurred; the greater part of the "black part of the world", in relation to external and internal properties, thinking and feeling, knowledge and abilities of its population, is a rather monotonous whole. “Africans,” Frobenius said in his article on the imaginative art of this population, “Africanized all material, and therefore everything brought to them from outside is faded.”

The religion of African blacks is generally one step lower than the religion of the Pacific-American group of peoples, with which the religion of blacks has the similarity that inspires all sorts of objects and partly consists in the worship of ancestors and animals; but it does not achieve the same high development of cosmogonic and mythological notions. The faith of the Negroes in the immortality of souls is reduced to the belief in ghosts; endowing animals, plants, stones and works of the human hand with miraculous spiritual powers leads Negroes to fetishism, to the superstitious worship of a wide variety of objects that become sacred due to some circumstance or witchcraft. Fetish ministry has reached its greatest development in North and Central Africa. But real humanoid idols are more common on the shores of the Atlantic than on the shores of the Indian Ocean.

The places in which blacks have fetishes, replace the tribe with temples. In the most diverse forms, in the most remote places, in the strangest decorations, fetishes are looked at both the initiates and the uninitiated. Therefore, the architecture of the temple itself in blacks can not be considered.

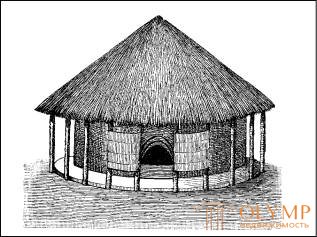

Fig. 65. Hut Marutse-Mambund kingdom. Across the Blue

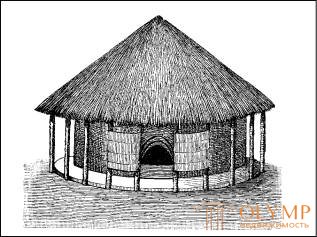

Fig. 66. Monbuttu Hut. By Schweinfurt

Negroes in the construction of dwellings dominated by a cone shape with a round or oval base. In the dwellings of the simplest type, the walls and the roof are not separated from each other. A hut woven from reed or woody branches that has no windows and is equipped with only one low entrance looks like a beehive or a real cone, such as Kaffar-Zulus in South-East Africa and the vagandans and vaniiroi that are anthropologically higher in the area of the origins of the Nile - the tribes whose huts of chiefs, built very carefully, with a canopy over the door, represent the highest stage of development like hives. Huts with a cone-shaped roof and a cylindrical wall, found in most tribes of Central Africa along with hive-like dwellings, are on a higher level. This roof rests on the wall itself, then on the vertical supports that surround it outside, so that a gallery appears like a veranda, then finally on the supports inside the hut, and a gallery is also formed between the supports and the wall. As characteristic specimens of the second type, one can point to the huts of the open Blue Kingdom of Marutse-Mambunda (Fig. 65), and specimens of the third type - to the Bitshuans' huts in South-West Africa. But in America you can also find a rectangular base of huts. It comes across in the pile structures of the Lakes of Moriah on the African Plateau, full of rivers and swamps; with a higher state of art on this basis, a slightly vaulted roof of leaf stalks of raffia palm is erected, such as, for example, in the Monbuttu tribe in central Africa, who visited Schweinfurt (Fig. 66); the same basis prevails throughout Congo, in the Ogowe, Gabun and Cameroon areas, where spacious and comfortable houses are often built on it. If we turn to the northern borders of Negro art, to the region of Niger-Benue in Sudan, where blacks have a high northern culture, we will see that the superiority of the inhabitants of this band in terms of art is manifested precisely in the architecture of the houses. In the house of King Umorussa in Vida, according to Flegel’s testimony, carved wooden columns support the low thatch roof, and the casement doors, like the columns, are decorated with elaborate carvings. To the south of Vida, on the Guinean coast, that is, again in a purely Negro country, in its ancient main city, Benin, conquered by the British in 1897, the semi-historical world of art was discovered, of which there were reports of Europeans in the 16th century. Here architecture seems to have achieved more development than anywhere else in tropical Africa. The supports of the veranda, as well as the beams of the flat ceiling in the royal palace, above which pyramidal towers were raised, were decorated with luxurious relief bronze plates, and a huge bronze serpent, wriggling down from the middle ledge of the roof. The finds made here have confirmed the fidelity of the ancient descriptions. In the Berlin and Dresden museums of ethnology there are heads of such snakes the size of nature.

In the Berlin and British museums you can also see bronze plates, which depict the very truthful entrance to the palace, occupied by Blacks guardians and decorated with the severed heads of Europeans.

Sculpture - the main art of blacks, to which almost all of them exhibit some ability. And they have in this art the primary role played by wood and wood carvings, usually left unpainted; but along with it, especially in West Africa, ivory carving is common; cast metal figures also have no shortage, and the bronze pieces of the Guinean coast can even be considered the most illustrative works in all ethnographic art. Nevertheless, the sculpture of blacks has a completely different character than the plastic of the Pacific and American tribes. She - sober and realistic. The fantasy of blacks is not inclined to a bizarre combination of figures of people and animals, and everywhere where these figures would be in the meaning of the genealogical tree of the above-mentioned tribes, leads them to a simple, natural relation of one to another.

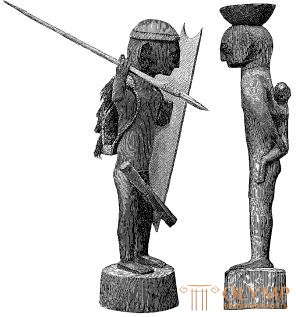

Fig. 67. The figure of the female ancestor of the Negro bongo. By Schweinfurt

In African sculpture, it is impossible to draw a sharp line between idols, images of ancestors, often called "images of souls", sculptures in memory of the dead, and between the free creatures of art. But it is instructive to trace in this sculpture the transition of barely scheduled semigeometric forms into completely natural forms and into their exaggerations, although even in some cases the path could be regressive. The guarding earrings of the Bamangvato sorcerers (betshuanov) in the Munich Ethnographic Museum strongly resemble human embryos. The magic doll of the Bari tribe living in the upper region of the Nile (the Vienna Court Museum), as it were, with conscious stupidity flaunts its forms of an undeveloped person. The statues of ancestors jutted in front of the grave of sergeant-sergeant Yanga of the bongo tribe, near Moody, published by Schweinfurt, are clumsy figures made with naive incompetence (Fig. 67). A few years ago, Frobenius pointed out how in all parts of Africa, on the graves of noble people were exhibited on the staves of the noble heads that followed with them into the afterlife, how, thanks to the worship of skulls, these pillars of spirits turned into images of ancestors and how from these pillars human figures. Thus, a long neck, similar to a stick, or a thin, long body, resembling a pole (sometimes it characterizes Negro plastics), are the remnants of poles from which these figures originated.

In the Berlin Museum of Ethnology there are many wooden Negro figures belonging to the higher stages of development; but these sculptures never differ in the monotony of execution as we see, for all their immaturity, in figures from Easter Island, from New Zealand or from North-West America. Every black man - a realist, a dreamer and a comedian in his own way. The figure of a kneeling woman with cups and a child behind her from Dagom, stored in Berlin, can serve as a good example of a relatively faithful nature image of a man, in which, however, the features of the Negro race are exaggerated. A wooden figurine of a woman breastfeeding a child from the Loango shore, published by Yust, represents a clear example of a conscientious desire for a living characteristic, as indicated by the teeth in the big open mouth of this figure, her hunchbacked Jewish nose, really found on the said shore, her decorative scars . Wooden horned idol from r. Niger (British Museum) - a sample of fantastic works of Negro art, in which from scary to funny - just one step.

The most fantastic work of blacks in woodcarving is Cameroon boat noses, which can be seen, for example, in the Berlin and Munich museums. By mixing animal and human figures, by eye ornaments that are rarely found in Africa, by the abundant coloring in black, white, red and green, these works of the German possessions in West Africa are closer to the works of German Oceania than all other objects of African art. “Maybe,” says Heinrich Schurz, “the future will clarify to us the history of these strange works, which apparently should shed light on many new tasks.”

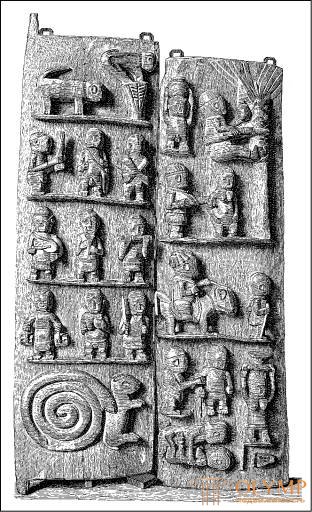

We have already talked about the carving on the door pillars and door leaves of Gauss blacks in the Niger-Benue region. In this ornamentation, in addition to concentric circles and rhombuses, there are large animal figures. Of particular interest are the two carved doors of the leader's house in Ayr (Fig. 68), which fell into the Berlin Museum of Ethnology. Here, in several rows placed one above the other, figures of people and animals are depicted in a bas-relief and events are described, the content of which is of ethnographic interest only. With regard to execution, they stop their attention not so much by the shapes of the dense, squat, clumsy figures depicted, but by the strict exposure of a primitive bas-relief. This was noticed by Julius Lange. People are presented now in front, now behind, then in profile; animals, surprisingly bad in pattern, are depicted as their side. Be that as it may, the content of these images, which Flegel asked for the sash owner to be explained to him, is very instructive for judging the Negro art. On the first platform of the first shutter a monkey is depicted, which, being pursued by a leopard and fleeing from it, climbed a tree. On the last platform of the second leaf is a man who is being held back from killing the seducer of his wife. But between all the events depicted it is difficult to establish any kind of internal connection. It is clear that the stage of art on which these reliefs stand has nothing to do with the original stage, which includes works of hunting and fishing peoples.

Nevertheless, it still corresponds to the famous prehistoric stage of art.

Much better than these Sudanese Negroes living on the border of a higher culture, depict the Negro animals living in the immediate vicinity of the Bushmen, especially the aforementioned Bethusheans, who are superior to many other tribes in their wood carving. They usually give the pens of their spoons the shape of animals, most often the giraffe, and one cannot help wondering how, with all the ineptitude of the design, these giraffes are true to nature and at the same time stylized. The concept of these subjects can be compiled from the samples stored in the Dresden Ethnographic Museum and the Berlin Museum of Ethnology (Fig. 69). Entire vessels made in the form of animals in Africa are less common and not as characteristic as in America. However, in the city museum in Frankfurt am Main there is a Zulu wooden vessel shaped like a tortoise.

Fig. 68. The door leaves of the chief's house in Ayr. From the original

Fig. 69. The handle of the Biteschuan spoon in the form of a giraffe. From the original

The casting of artistic metalwork from blacks is most developed again in Benin, whose bronze production, which existed in the 16th and 17th centuries, drew the strong attention of Europeans. After 1897, bronze heads, bronze utensils, mainly bronze plates with relief images, were brought to Europe in significant numbers. Among the rarer whole figures, animals are more common than humans. The lion's share of these subjects received the Berlin and British museums; but the ethnographic museums of Hamburg, Dresden, Vienna, Leipzig were not left without them. The collection of the British Museum is published by Reed and Dalton. The Berlin collection was published by Lushan, who already wrote about her. Opinions differ on the appointment of large heads, equipped with a round hole in the upper part of the skull, sometimes with high headgear, with the neck and chin completely covered with beads. British scientists consider these heads to be vessels for storing elephant fangs adorned with luxurious carvings, and Lushan assumes the existence of a connection between them and the worship of skulls, dead and ancestors. In the best of these heads (the head from the Berlin Museum is remarkable), the Negro type is reproduced so truthfully, the individuality of the face is captured so true, the casting made with the loss of the wax model (b cire perdue) is so excellent that only the mature art of the cultural peoples can counterpose these products something like that. Plates with reliefs are often curved inward, as if to be filled with roundness. In addition to the palace images already described, these plates depict people and animals: people, short-legged, long-bodied, but not particularly big-headed, represent, like all black sculptures, some Europeans, namely Portuguese, in costumes of the XVI and XVII centuries, sometimes blacks, and they are mostly dressed and armed (Fig. 70, from the collection of Hans Meyer) and less often, probably only when it is alien tribes, naked and tattooed. Most of the figures face the viewer directly. Turns that go as a frontal rule are rare, but they occur. Of animals, predominantly important ancestors or fetishes are depicted: a leopard, a crocodile, a snake, a turtle, a shark, a monkey, a frog, and also an elephant, a bull, and an antelope.

Fig. 70. Bronze plate from Benin. From the photo

The figures are sometimes in one way or another relation to each other, which can be said about both blacks and whites; but depicted on the same plate in groups or separately, they usually stand still and look straight ahead. Все они выделяются на фоне, покрытом узорами чеканной работы вроде вытканных на ковре. На некоторых особенно старательно исполненных, удачных и старинных произведениях пластики, хранящихся в Лондоне, узор состоит из кругов и крестов, в огромном же большинстве случаев – из четырех лепестковых цветов, видимых как бы сверху и иногда потерявших один, два или три лепестка. По качеству работа бывает очень различна. Особенно интересно "дерево фетишей" или, как называли его Рид и Дальтон, "палка предков", очевидно надмогильный шест упомянутого вида, хранящийся в Гамбургском музее. Человеческие головы и животные и здесь находятся в менее тесной взаимной связи, чем, например, у океанийцев.

Нет ничего невероятного в том, что это бронзовое искусство занесено в Бенин в XVI в. португальцами, как говорили о том англичанам сами бенинские негры. Но при каком бы то ни было взгляде на произведения негров приходишь к убеждению, что они и это искусство усвоили себе и африканизировали. Рид и Дальтон согласны с Лушаном в том, что из сохранившихся произведений нет ни одного, которое не было бы делом негритянских рук.

From Benin, a bronze and brass casting technique has obviously spread throughout Guinea, where it is still flourishing in a modified form. “Modern works of Ashanti and Dagomeans,” said Lushan, “without a doubt, the essence of the last scions of ancient Beninese art; there is no shortage of works in a gradual transition from him to them, so we must assume a continuous exercise in this art that lasted several centuries. ". Compare, for example, the brass pole of the Negro blacks from Lagos in the Christy collection in London with the Beninese fetish tree in the Hamburg Museum. And this pole testifies to how natural, than Melanesians, blacks combine for symbolically decorative purposes the figures of people and animals.

Fig. 71. Stone tip Zulu tube with an ornament in the form of weaving. According to Ratzel

We also see a peculiar kind of relief in West African blacks in their ivory carving. A lot of small Benin art products made of this material, distinguished by primitive animation, have fallen into our museums. Of course, in terms of subtlety and freedom of execution, these arabesques, hardly carved on solid matter, cannot be compared with those bronze products, the shapes of which are initially molded from wax, but according to the material and design of the arabesques can be put on the same board with bronze works. Whole elephant canines were very skillfully turned into original art objects, and often the entire surface of the canine was covered with semi-relief carving. What is told and compared on these canines, we can only guess so far. On the elephant fangs of Benin, brought in large numbers to Europe, together with the bronze products mentioned, again, along with the images of blacks, are 17th century Portuguese. This kind of art existed all over the Guinean coast. Large European ethnographic museums are rich in a variety of works of this kind, decorated with many different figures: sometimes in the oldest cabinets of rarities they are considered medieval European works.

Actually the linear ornamentation of the blacks seems, at first glance, not requiring a detailed explanation. Dark triangles or semi-circles on a light background, rows descending or hanging from the top edge of objects or rising from the bottom edge, regular quadrangles arranged in a staggered manner, zigzag, parallel and intersecting lines are found in the south and north, in the east and west of the country occupied by non-gums , on a wide variety of objects, in a wide variety of types and, as it seems, have long played the role of only geometric decorations. From straight-line ornaments, South Africans carved on wood or stone, imitating weaving, deserve attention; their origin is more obvious than the origin of most other motives leading from textile. In fig. 71 depicts the Zulu tube tip decorated in this way (Berlin Museum of Ethnology). The crooked cross on the brass weights of Ashantians and tattoos in the r. Quilu. The hooked cross is found in India and Europe, in America and Africa, and we agree with Lushan, who remarked: "I personally still believe in the possibility that this sign appeared completely independently and independently among different nations and at different times."

Fig. 72. African ornament in the form of lizards. According to Vejle

In the Negro ornamentation there is also no lack of curves and wavy lines. Outlets on the sheath of a sword from Liberia (Stockholm Museum) give the impression of stylized flowers. On the bronze vessels of the Gauss blacks there is also a figure consisting of three similarities of the letter Γ, emanating from one common center. Considering these vessels, we again reach the extreme limit of real Negro ornamentation, which, like all ornamentation of prehistoric and primitive peoples, is distinguished by the rarity of the use of motifs of the vegetable kingdom in comparison with the use of human, animal and linear motifs.

But ethnology did not fail to explain the Negro, composed of the forms of man and animals, as well as linear, ornamentation in the same way as it was done with respect to Oceanian and Brazilian. Karl Weile pointed out that the lizard in Africa forms the basic form of a linear ornament and that different types of lizards can be recognized in various patterns, starting with a crocodile and ending with a gecko and a skink; sometimes these ornaments are overdeveloped, more often the weak form of their prototype (Fig. 72).

Negros, not affected by the ancient civilization of the Nile and the Mediterranean, despite their familiarity with iron and bronze processing, in essence can be considered a primitive people, but relatively Malays, this is true only to a certain extent, although ethnography ranks them as primitive peoples. Actually, the Malay world of Southeast Asia, again predominantly the world of the islands, borders on the ancient and cultural peoples of Asia in the north and west, and in the east comes into contact with the Melanesians and Micronesians, of whom we have already spoken. The modern study of our studies classifies among the Malays primarily the inhabitants of the Sunda Islands, Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Celebes, the Moluccas and the Philippine Islands. Ethnographically, these Malays are a mixed tribe with many varieties, and therefore their study from the point of view of the history of art comes up against many contradictions and difficulties. The ruins of huge buildings, of which the ruins of the Buddhist temple in Borobudur, in Java, with 555 niches for life-size statues of Buddha, do not belong to the semi-cultural state of the primitive people, but to the Brahmanian and Buddhist culture of India. The same can be said about the numerous stone and bronze Hindu statues of gods found here. Gorgeous green, brown and blue earthenware, often decorated with dragons, vessels that, according to Adolf Bernhard Meyer, belonged to the Borneo and the Philippines to the most valuable items of utensils in the native families that passed from family to family, these art treasures were brought from China for many centuries ago. Hindustan influence on the islands of the East Indian archipelago and trade relations with China existed at the beginning of the Middle Ages, perhaps even earlier. In the late period of the Middle Ages, Islam entered the Malay Islands victoriously. Instead of ancient Hindu temples, mosques began to be built, devoid of any grace; the art of casting bronze was forgotten; Arabic writing became the guardian of rather insignificant Malay history and poetry. Several centuries after that, the flow of European civilization poured into the Malay Islands, especially to Java, and Chinese industry began to compete here with European, displacing the ancient native fine crafts. Therefore, we would hardly have the right to speak of Malay art as the art of primitive people, standing on the metal age, if the ancient Malays did not retreat from the shores and from big cities to the mountains and into the islands. the form. About Java, perhaps, you can completely keep silent. In this case, the most interesting for us is Sumatra, Borneo and Luzon. Tribes such as the Batak on Sumatra and on the neighboring island of Nias, Dayaks in Borneo, Tagaly, Kiangans and Igrrots on Luzon make it possible to understand the original state of Malay art, and if we talk mainly about the Dayak art of Borneo, then only that they were best acquainted with this subject thanks to the book by L. R. Heyns.

Fig. 73. Batak Magic Rod. According to Ratzel

Prior to their intercourse with the Hindus and the Chinese, the Malays, as Crawford had already proved on the basis of their language, were engaged in farming and cattle breeding, weaving plant fibers, mining and processing iron, perhaps also gold, which only later were joined by copper and tin, pottery in which, however, they did not attain special mastery; they lovingly indulged in navigation and commerce and, having developed their own letter of the letter, were ready to cross the border of the primitive state; Meanwhile, their religious beliefs boiled down to the same cult of souls, ancestors, and animals as we saw in America and Oceania, and in some respects even approached the same fear of ghosts and the same fetishism that are observed in blacks. The cult of ancestors, the idea of the ship of the dead, bringing the soul to the afterlife, and the rhinoceros replacing the ship of the dead, as soon as the afterworld is transferred to the clouds, impregnated the artistic imagination of the Malays. Images of ancestors, piled on top of each other or located in the form of a number of figures of people and animals, similar to those we saw in Melanesia, especially in New Mecklenburg, and in America, among northwestern Indians, Shurtz recently found in the Batak. As samples of such images, you can point to the magic wands stored in the Leipzig and Dresden ethnographic museums (Fig. 73); The most complete embodiment of the myths about the ship of the dead can be considered the Batak model of a coffin in the form of a ship with the head and tail of a rhino bird, in the Dresden Museum, and the Dayak picture with similar ships, in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology. If, in view of this, nothing is impossible in that the ancient Malay culture served as the starting point of all the Malayan, Polynesian and northwestern American art considered by us, then it cannot be denied that the art of this zone went another, perhaps even the opposite way. In the study of the art of primitive peoples, the sequence in which phenomena that existed at the same time evolved one after another still almost constantly eludes us. Scientific research in this case now and then falls into the back streets.

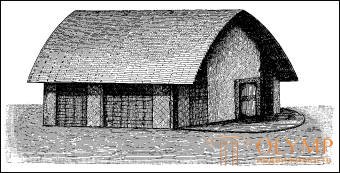

Fig. 74. Batak House. With models from the Dresden Museum of Ethnography

The architecture of the homes of the Malays has a very definite imprint. Among primitive peoples, they are the most ardent lovers of piles, and where foreign influence did not act on them, they still remain faithful to pile constructions. Even on land, they arrange their homes, usually on stilts, sometimes towering more than 12 meters. Palembang City, in which the main street is played by the Musi River, is the Venice of Sumatra, the city of pile structures on the water; Dayak villages in the virgin forest in Borneo and the villages of Tagal and Igrorot described by Hans Meier on the mountain peaks of Luzon consist of pile villages on land; the capacious family houses of the Batak on Sumatra and the single-cottage dyaks of Borneo are kept on stilts in the same way as the smallest huts of these islands. All Malay tribes have a general rule - to build housing with a quadrangular plan, so convenient for pile structures; round, oval or octagonal structure found only as an exception. A high steep roof, representing sufficient resistance to tropical rains, is sometimes sloping, sometimes with a gable, then combines both the slope and gable (Fig. 74), such as the Batak, for example, whose oblique gables rise above the steep roof slopes. More extensive buildings in the rare case are not equipped with verandas, which, however, are sometimes replaced by an open plank platform, freely laid between the piles at the height of the lower floor. To connect the individual parts of the building, the ancient Malays used only bast ropes or rattan loops. There is no shortage of decoration and decoration of houses. At the Batak, the outer walls are painted on a white background with numerous black and red ornaments or images of animals, and the top of the gables is decorated with carved symbolic bull heads carved from wood. Do igorrotov found sculpted on the door pillars of human figures. In Dayak gables are usually covered with abundant carvings, often representing curls, and to the walls and on the beams are attached "carvings of demons and various ugly masks", sometimes clearly indicating Chinese influence.

Fig. 75. Chiang Ancestral Sculptures. By A. B. Meier

The ancient sculpture of the Malays is essentially wood carving, although almost everywhere they also have rough stone figures. And in this sculpture the main role is played by the sculptures of people, sometimes issued as images of ancestors; but along with them there are also such human figures, which, although they are not objects of worship, are, however, considered to be personifications of good or evil spirits and in some places are placed at the door pillars, near the grave houses and on the roads for aversion of evil spirits. Although these figures are not as bad in relation to their general proportions as the Melanesian ones, and do not have such ugly large heads, in Malay sculptures human forms are no better conveyed than in Melanesian ones. However, between the figures belonging to different islands and tribes, you can notice some typical differences. The idols and figures of the ancestors from Nias Island, mostly crouched and with their heads covered, with careful work and the correct number of fingers and toes, have sharp facial features, thick lips and short, upturned noses. Much more ugly are the similar figures of the Batak in the Dresden collection: their heads are oval, their faces and noses are flat, the members of the body are disproportionate and shapeless; the overall impression they make is extremely small. On the contrary, the Dresden figures of ancestors, brought from igorrots from the island of Luzon, are notable for their expressiveness; true, and in them the mutual relation of body parts and the shape of its individual members are transmitted with surprising negligence, but the faces with their Mongolian eyes and noses curled down are very typical, and in movements and postures, the desire to reproduce individual life is expressed. In fig. 75 depicts two figures of ancestors - works of kiangans, closely related with igorrotas: a woman with a child on her back and a warrior with a raised hand.

Fig. 76. Dayak Knyalan. According to Hein

Fig. 77. Dayak shield. According to Hein

Speaking of Malayan carvings, representing a mixture of figures of people and animals and related to the religious ideas of this tribe, we have already mentioned the stylistically carved magic batons of the Batak. These subjects include the so-called Knyalan Dayak (Fig. 76), the Vienna Court Museum. These uniquely arranged and painted carvings used during ceremonies at hunting festivals represent strange combinations of animal and human figures on the back of a stylized rhino bird. If we take into account the purpose of these objects, the mythological significance of the fairy-tale bird and the external similarity of these works with the products of Melanesians and north-western Americans, then we will have to, together with Schurz, recognize them as important links in a common chain of similar images.

The original painting of the ancient Malays can be called pictography rather than painting pictures. This can be said even with respect to the large Dayak tables published by Grabowski, depicting the ships of the dead. But painting plays an important role in the decorative art of these tribes. To verify this, it is enough to look at the Batak houses and the Dayak shields. Here it is impossible to separate the painting from the ornamentation.

But in this area, the original Malayan forms are obscured by such a layer of Indian, Chinese, and Arabic motifs that it is almost impossible to recognize what was originally the property of the Malays.

Fig. 78. Sword handle from the island of Java. According to Hein

Fig. 79. Ornament, consisting of curls and volutes, from the island of Sumatra. According to Hein

The Malayan ornamentation, borrowed from the animal world, in images on the plane reveals an undeniable tendency to turn into geometric shapes, and in Malayan circular and curvilinearly curving patterns one can see a desire to imitate plant forms, caused by acquaintance with Indian and Chinese ornamentation. Tigers and dragons of Chinese shields turn on Dayak shields in the faces of demons with their eyes bulged, mouth open and huge fangs, sometimes with the remnants of the forms of the human body. On the Dayak shield, which is stored in the Berlin Museum (Fig. 77), all this is clearly distinguishable, but on the shield from the internal parts of Celebes, in the Leiden Museum, the components of the image are so scattered that you need some skill to see something whole in them. The 400-year-old sword hilt in Vienna

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)