In the study of the initial pores of art, the millennium can be viewed as one day. Modern wild nations are the direct heirs of the once-existing prehistoric peoples. Ethnology highlighted some dark sides of the prehistoric era. Ethnology and the study of the prehistoric period clarify and complement each other. For the history of the development of art, the study of the prehistoric art of cultural peoples who subsequently achieved perfection is often more instructive than observing the artistic creativity of wild tribes, whose position — whether they descended from a higher level or settled on a certain point — is always different either by absence or at least least, the paucity of development. But the creativity of wild peoples gives us the opportunity to understand many aspects of the original artistic activity, which in prehistoric art are forever immersed in darkness. If, for example, with respect to prehistoric peoples, we can only assume that they, along with stone and bronze works of art, existed in rich wood carvings, then we will see a graphic confirmation of this in the wooden products of savages; if the remnants of red dyes found during the excavation of the diluvial antiquities of Brittany, allow us to guess that prehistoric peoples used paint to decorate themselves, then the custom of savages to illuminate their own body seems to be an obvious confirmation that this tradition is one of the main manifestations of art in its original it's time.

The art of all savages begins with decorating your own body. Like Justus (Joest), we distinguish body coloring and painting with cicatrices from tattooing. When painting the body, a paint is induced on its surface, which can be washed off and replaced with another, and the body is covered with one color or a variegated pattern. Painting with the help of scars is made by scratching the skin with a stone knife or a piece of shell. Repeated on various places of the body and, moreover, in the form of certain patterns, plastic, protruding pale scars themselves form an ornament. The tattoo consists of scratched and punctured patterns, which, after the introduction of the coloring substance through the skin, remain on the body forever, not disappearing after the inflamed area heals. This substance is commonly used as a charcoal powder: translucent through the skin, it gives the pattern a blue color.

To a certain extent, a parallel can be drawn between prehistoric and ethnographic art . The art of the diluvial stone age corresponds to art at that stage of life of wild tribes, when they are hunters, fishermen, collectors of plants, especially the art of Australians, Bushmen and the northern polar peoples. The art of the newest stone age continues to exist among the tribes engaged in a little farming and animal husbandry, and even now, strictly speaking, belonging to the stone age; in this case, the parallel is the more obvious that, as Ratzel argues, there is an ethnological and anthropological connection between these tribes, namely, the inhabitants of the Pacific islands, on the one hand, and the American Indians, on the other. With the art of the prehistoric bronze epoch, one can compare the art of savages who are familiar with metals, but who use mostly iron, and not bronze; it should be borne in mind mainly Negroes and Malays, since alien higher civilizations do not take advantage of their culture, like the culture of the prehistoric Hallstatt period, which invaded more than once in the culture of the Bronze Age. Of course, we are not talking about the present life of primitive peoples, but about their state, in which they were at the first contact of the Europeans with them.

By their skill, the savages who did not go beyond the stage of hunting and fishing , who lived in the extreme northern and southern limits of the inhabited countries of the world, resemble diluvial mammoth and reindeer hunters because they are unfamiliar with mining and processing of metals, with weaving and pottery, with farming and cattle breeding; then, the resemblance between these peoples, as Andrei was the first to point out, is that, despite all their lack of culture, they show an amazing ability to draw. The same reasons have the same consequences here and there. The eye, which has excelled in observing the animal world, and the hand of a hunter, accustomed to falling into the beast, generate on the steps of the beginnings of every culture the art of drawing animals that is true to nature. In general, despite all the similarities in the manifestations of art at this stage, we already see differences here, determined by climatic, geographical and ethnographic conditions and overlooked by the latest views, but whose significance cannot be ignored.

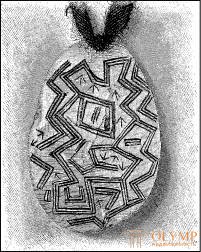

Fig. 39. Australian, made of a shell, ornament with a labyrinth ornament. From the photo

Dark-skinned Australians decorate themselves not with a tattoo, but with patterns from the scars protruding on a dark background in the form of light stripes. They paint both the body and their utensils with white clay, black charcoal and yellow ocher. White stripes are considered everywhere as festive clothing, while white color, sometimes devoid of any drawings, is an expression of sadness; red color most of the Australians adorn themselves, going to war, but also gives it their dead, going to the afterlife.

About the architecture of the Australians, we can not talk. For many of them, caves and pits in the ground serve as dwellings. Others, to protect themselves from wind and weather, stick several tree branches into the ground or are content with flat, resembling niche huts made of brushwood, or wallless roofs, making a fire in front of them.

Australian decorative art deserves more attention : those painted or carved linear jewelery with which Australians supply their wooden weapons and utensils. The grooves formed by the incised lines are sometimes filled with red or white, less often with black paint. Often, but not always, one should distinguish from these decorative patterns signs indicating that a thing belongs to a known person or family. The transition from the language of signs on the baton sticks to the ornament is also not always clear. Circles and parts of circles connected on the Australian magic bars with longitudinal and transverse stripes, as we have every right to suspect, have a deeper meaning than it seems at first glance; the same can be said about the scrawled, angular labyrinths of lines on the Australian shells used to cover the nudity, which can be seen, for example, in the Dresden Ethnographic Museum (Fig. 39). There is also no doubt that the geometric patterns found on many Australian shields, throwing boards (wommers), clubs for striking and throwing (boomerangs), as well as baskets and mats, are just decorations. Simple or rhythmically placed and embedded parallel lines, zigzag lines, undulating or arcuate lines, as well as patterns consisting of punctured points and forming surfaces that look like a chessboard field, may well be of the same origin as this kind of prehistoric ornamentation, which we tried to explain above. The peculiarity of the Australian ornamentation is the filling of many fields with parallel shading, and the quadrilateral fields with parallel quadrilaterals, decreasing in size as they approach the middle of the field.

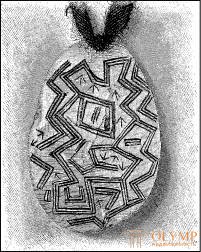

Fig. 40. Australian shield. According to Grosse

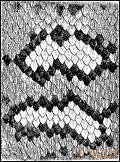

Some seemingly strange, ornamental motifs of Australian ornamentation, seemingly distinguished by the free, fantastic play of irregularly wriggling stripes, spots and geometric figures, should be seen as generated by the observation of nature, which, as we have seen, lies at the base of many simple linear patterns. patterns. The above-mentioned Australian patterns are most often found in a painted form on the outer side of Queensland shields: on a white background of various shapes, a part is red, a part is yellow, bordered with black stripes. On the shield, located in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology (Fig. 40), we see a white background, on it in red are given the average pattern and crosses, the other fields are yellow with a black border. Such shields, the overall color of which represents the characteristic Australian range of colors and produces a magnificent harmonious impression, are also found in the ethnographic museums of Munich and Dresden. Ernst Grosse explains that they represent an imitation of the patterned skin of snakes, and if you take into account only the general impression, this explanation will seem all the more likely that the Australian snake Morelia argus fasciolata (Fig. 41) is covered with yellow and brown spots that are equally strictly repeated and irregular. Forms outlined with a black border on a lighter background.

Fig. 41. A piece of skin of the Australian snake Morelia argus fasciolata. From nature

Along with linear and spatial ornamentation, Australian art has resorted to decorating weapons and utensils to depicting animals and people. This kind of ornamentation, devoid of style, is apparently derived from the use of a symbolic language; some tribes consider many animals sacred. These are their kobongs (totems), their heraldic animals, as we would call them now; therefore, they are very often scratched on the shields or on the tribe’s offensive weapons, and they are surrounded by linear contours. Human figures are found in a similar meaning. But who can explain what sense, for example, rough figures on religious throwing bars stored in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology, or on throwing boards of the Dresden Ethnographic Museum have?

Fig. 42. Australian pattern on the wall of the cave. According to gray

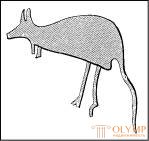

The original experiments of monumental wall painting , preserved in Australia, are peculiar to all these ornaments . On the walls of the caves and on the coastal cliffs of the northwestern, northern and eastern parts of this country, there are painted and scratched drawings depicting scenes from the lives of people and animals, partly ancient, partly modern. First of all, let us point out the open Gray in the late 1830s. the images on the walls and ceiling of the three caves on Upper Glenelg, in Northwest Australia; This is mainly a picture of people and kangaroos, painted with red, yellow, black and partly blue paints on a white background (fig. 42, 43). The crown of rays around the head of a human figure is obviously nothing more than a feather headdress. A face without mouth resembles images from a prehistoric era (see figs. 13, 16, and 31). You can then point to the numerous images of animals and people found by Stokes in the 1840s. on the coastal cliffs of Despous Island, in Northwest Australia. These drawings inside their contours are recessed into the reddish upper layer of stone, with the greenish core of the latter exposed. Some animals, such as kangaroos, fish with their offspring, water birds, crabs, beetles, are depicted relatively true (see Fig. 43), while people and scenes in faces are less clear and clear. This also includes contour drawings of similar content, recessed into the cliffs by whole inches, as described in 1879 by Nicholson.

Fig. 43. Kangaroo. Australian pattern on stone. By stokes

They are found in the vicinity of Sydney, on the southeastern coast of Australia, some of them exist, obviously, not for one century. Finally, they include drawings of central Australians made public by Spencer and Gillen, possessing only stone knives and stone axes; these are written on the rocks, slightly stylized animals that show the tendency to turn into geometric figures, sacred signs of totems, which can be taken for images of natural objects, as well as geometric figures, among which are often found concentric circles; All this is painted with childish incompetence and illuminated with white, red, yellow and black colors.

The first steps of the Australian easel painting can be considered drawings of soot on the bark, which the natives bring to remarkable perfection. Smith (Brough Smyth) has published some excellent images of this kind. Of course, in these images, often rich in content borrowed from the life of savages and their relations with whites, the perspective is completely absent in exactly the same way as the distribution of light and shadows. But the details are usually spotted accurately and transmitted vividly, although the fingers or the legs are sometimes miscalculated. It is hard to say where European influence begins on many of these images, but in general they prove that Australian natives have a great innate ability to believably and boldly depict observed objects on the plane, especially local animals. Animals are usually presented in profile, people - en face. But this infant art is not yet subject to any rules that would have been created by the savages themselves: each draftsman is guided by his own inspiration.

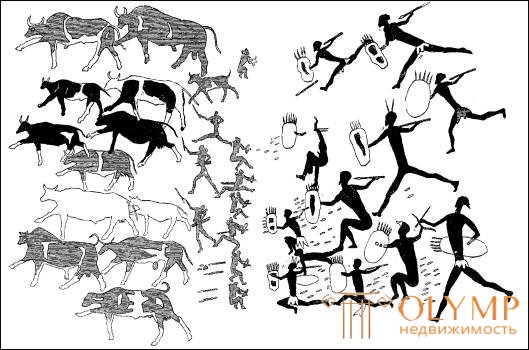

Fig. 44. Bushman drawing in a cave near Hermon. According to Andrew

South African bushmen, the “unfortunate children of the present time,” as Fritsch called them, in spite of lighter skin color, in no way stand at a higher level than the Australians, but differ from them in both body color and some other features. The national weapon of this "most decisive, one-sided and clever hunting tribe of all we know" (Ratzel) is a bow and arrow, which the Australians lack. Jewelry, among which already colored glass beads play a role, as well as iron arrowheads, are received by the Bushmen from their black neighbors, who have reached a higher level of development. Instead of scars, which would not stand out on their fair skin, they use a real tattoo, but they only carry out insignificant strokes and stripes, which never form real patterns. The construction of huts is given by the Bushmen even more difficult than by the Australians; they usually live in caves and under sheds of rocks, in mountains, their geometric images do not have to be spoken, since decorative art hardly ever exists among them. But for all that, among the Bushmen, we see the most striking examples of the depiction of animals, which we find in general among prehistoric and primitive peoples. Their drawings and paintings on the cliffs exceed Australian size, diversity and skill. "Not a single tribe of South Africa, right down to the inner parts of Central Africa," said Golub, "did not come to such art of working stone as the Bushmen showed. Bushman dispersed his boredom by carving on stone, producing it with the help of stone tools; using these same tools , he decorated his extremely unpretentious dwellings, proved his artistic abilities and created for himself monuments that will last the longest of what other local tribes have done. " In some places where the Bushmen now live or where the Bushmen used to live, at every step there are images made on blocks of roadside rocks, at the entrances to caves, on the steep walls of the cliffs, and such decorated with images points extend approximately from Cape of Good Hope across the Cape Colony far beyond the Orange River. As in Australia, these images are illuminated with red and yellowish ocher colors, joined by black and white; the drawings are made on the light background of the rock or are hollowed out in contours on a dark cliff with a harder stone than they are. The most common are single figures of African animals, such as ostriches, elephants, giraffes, rhinos and various antelope species, as well as domestic bulls and, in modern times, horses and dogs. People are also depicted, and the figures of Bushmen, Kaffirs and Whites retain their characteristic features. Images of animals are found in whole thousands one near the other. The same animal artist, as if for the sake of exercise, reproduces countless times, with the images arranged in rows; Sometimes, when it comes to scenes of hunting, fighting, military campaigns and expeditions for prey, people and animals are mixed in the same picture.The most well-known image published by Andrew, which was copied by the French missionary Diterlen in one cave, located two kilometers from the mission station of Hermon (Fig. 44): Bushmen stole their herds of bulls from kafirs; the herd is stealing to the left, the kafra, armed with spears and shields, rush after the robbers, who turn around and shower their long-legged enemies with a cloud of arrows. How clearly expressed here is the difference between tall black kafirs and squat white-skinned bushmen! How well and truly drawn running cattle! How beautiful and lively the whole incident is! But the perspective removal and distribution of light and shadows are just as small here as in the drawings of the Australians. Regarding all other images of this kind, copied or brought to Europe, we must saythat Gutchinson and Buttner’s reports of the existence of prospective images among the Bushmen are based on a misunderstanding. Individual animals, drawn in the form of silhouettes, appear entirely in profile (Fig. 45). To verify this, enough of those drawings that, thanks to Golub, entered the Vienna Court Museum and the Karlsruhe collection.

Fig. 45. Бушменский рисунок. По Фритшу

Если мы перенесемся из южной части обитаемой земли в более холодные страны, то и в них встретим подобные художественные попытки, хотя и отличающиеся местными и этнографическими особенностями, но выражающие столь же низкую ступень культуры. В Северной Америке область обычаев и искусства эскимосов простирается от Гренландии до Берингова пролива. К этой области с северо-востока примыкает область чукчей, которые, хотя и содержат стада полудиких северных оленей, однако не могут быть отделены от эскимосов, как народ, имеющий свое оригинальное искусство. Норденшильд, лучше других познакомившийся с чукчами, ставит их даже ступенью ниже, чем эскимосов.

In recent times, iron and copper have been brought to all these Arctic peoples; they themselves, as before, process only the skins, stones, bones, horns of reindeer and walrus tusks. Hans Hildebrand quite rightly says about them: "A people who do not know the art of metalworking are still in the position of a man of the Stone Age, although he possesses this or that metal object."

The harsh climate in which these people live, forced them to surpass the Australians and the Bushmen in their ability to make clothes and make homes. True, the clothes of the northern peoples consist exclusively of animal skins, but they nevertheless skillfully make skirts, jackets and trousers of the latter. True, the summer dwellings of these peoples are usually tents made of hides, kept on props of floating wood and whale fins; but for a long winter, most Eskimos build themselves domed snow huts consisting of a round or oval main room and several surrounding rooms. The central Eskimos in northeastern America, according to Boas, build even extensive huts divided into several rooms and covered with domes out of snow, and thus receive public houses in which they gather to sing and play together.

Fig. 46. The yoke of the Eskimo drill with the image of animal skins. According to bastian

Polar peoples forced to wrap themselves do not particularly care about their bodily adornment; nevertheless, women in North America sometimes tattoo parts of their bodies with simple patterns consisting of rhythmically and symmetrically arranged points and strokes. But the inhabitants of the north are not strangers to the aspiration to decorate their fur clothes in an appropriate and original way, and especially diligently adorn any utensils made from the bone of antediluvian mammoth canines, reindeer horns and walrus tusks. Bows, rocker arms of gimlets, handles of boxes and buckets, smoking tobacco pipes, etc., are not observed by Eskimos living in North-West America (from the Greenland Eskimos), are thickly dotted with scrawled ornaments filled with black, less often with red paint and on the end they are equipped with carved animal heads or similar decorations. Geometric linear patterns are relatively rare and do not go, as Grosse has already noted, further than the simplest motifs of a ribbon, a seam, a scar; while the often depicted individual and concentric circles imitate partly beads strung on a cord, partly images of the moon and sun. There are also concentric circles connected by tangents and giving the impression of spirals. But the prevailing motifs of the ornamentation of the polar peoples are again borrowed from nature and life, especially from the world of northern animals. From simple ornamental rows of stretched animal skins, grazing deer, looking out of the water of walruses, fish swimming one after another and rhythmic rows of various similar animals, sometimes joined by a decorative row, alternately consisting of summer tents and people, similar to figure letters, above all to the picture narrations about the life of the north-western Eskimos and Chukchi. In this kind of paintings, processions of hunting and fishing, wandering and homework, celebrations and disputes are presented. Remarkable is the clarity and liveliness with which these children of nature, who depict the human head only in the form of a black circle, can tell their story. These vivid life stories, which should be viewed as a transmission of history, are often very complex and, as pointed out by Walter James Hoffmann, repeating one near the other and changing their appearance, gradually turn into decorative stripes; probably, their initial development in general occurred exactly in this way. The language of human gestures, depicted graphically, immediately becomes a pictorial letter, and the events presented schematically, immediately turn into a decoration. Among the items adorned with a simple range of decorative motifs are the rocker drills with a repetitive animal skin pattern, kept in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology, and an Eskimo headband, adorned with a number of plastic seals and in the Vega collection in Stockholm (fig. 46, 47) .

Fig. 47. Eskimo headband. According to Hildebrand

Fig. 48. Mother and child. Carved figure. According to Hildebrand

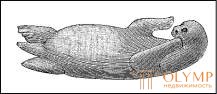

In addition to the plastic decorations on the ends of the instruments, among the Eskimos and Chukchi we find true fine art in a well-developed small sculpture. In bone carving, mammoth tusks, reindeer horns and walrus teeth, the polar peoples are the direct heirs of the Paleolithic artists carving the reindeer horns, and the inhabitants of the French caves. Their human figures, such as the figure of the Chukchi (fig. 48) from the Stockholm collection, are obviously no more artistic than the prehistoric human figurines found in the mountainous France, but they are better preserved and therefore it is more convenient for them to see that strict Yuli Lange expression frontality, from which there are as few exceptions in the art of wild peoples as in the art of prehistoric peoples. Plastic figures of animals are captured and transmitted correctly in general terms, but in terms of vitality and artistic processing they are inferior to the best prehistoric works of this kind. We find in polar peoples plastic images of almost all northern animals, mainly large marine mammals, whales, walruses, seals of various species, then polar bears, foxes, water birds; but it is the reindeer, so often found between the plastic images of the ancient European hunters on the reindeer and in the scratched drawings of polar peoples, that the latter almost do not come across in the form of plastic figures. Probably the body shapes of these animals are too complex and elusive for arctic carvers. In fig. 49 - a lying on the back seal found among the Aleuts, Vega collection, in Stockholm. The National Museum in Washington and the Trade Museum in San Francisco are rich in arctic and carved works, and the Berlin Museum of Ethnology and the Munich Museum of Ethnography are in Germany.

Fig. 49. Seal. The product of the Aleutian small plastic. According to Hildebrand

As for the purpose of plastic works of this kind, they are considered partly bait for fish, partly toys for children and adults, partly decorations of clothes and dishes, partly amulets and protective pendants of a mystical-religious nature. There is nothing impossible in the fact that some small objects of this kind are nothing more than products of a free aspiration for art. The question of the development of all this Eskimo art was studied by Hoffmann. Attempts are being made to prove that some of the ornaments were influenced by the Indians of the guide, on others by the Chukchi, on the third by even the Papuans of the Torres Strait; it is proved that here the straight-line ornaments express a more ancient, and concentric circles - a later stage of development. But, fortunately, Hoffmann also recognizes that these concentric circles are not borrowed from the Papuans, who have similar round-shaped ornaments, and have emerged independently here and there and in other countries.

In general, we see that the art of all these hunting and fishing nations is not alien to supersensible and symbolic representations. But his realistic character appears even brighter everywhere. It convinces us that art in general does not begin with symbolism, but with observation of nature.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)