The inhabitants of the Pacific Islands and the inhabitants of the forests and steppes of America by tribal affinity, by the similarity of beliefs and the uniformity of family life based on maternal law, are presented in the light of contemporary sociology, forming one circle of peoples, which Ratzel called Pacific-American. If we exclude from this circle American cultural people and Malaysians who are familiar with the use of iron and are often in contact with a higher Asian culture, then we will be dealing with a group of such people who are not out of their natural state, similarities of lifestyle and artistic crafts can be combined into one.

The founders of this ethnographic view consider America not as the distant West, but as the most distant East, so that in their eyes the western coast of this part of the world does not appear to be the western edge of the inhabited earth, and the eastern coast is its eastern edge. The western border of the Pacific-American region of peoples coincides with the eastern border of the vast region of the Malay Islands. The split line coincides with approximately 130 ° longitude east of Greenwich. From the east, from this line and south of the equator, extends from New Guinea to the Fiji Islands, the region of Melanesia (or the area of the black islands); north of the equator, from the Palau Islands to the Gilbert Islands, lies in the Pacific Micronesia (a region of small islands), while the third region - Polynesia (a region of numerous islands) occupies a huge triangle in the middle of the Great Ocean, the corners of which make up Southwest New Zealand , in the north - the Sandwich Islands, in the south-east - Easter Island. The ocean world of the islands, as well as the American continent, as far as it is appropriate to talk about them in this department, we can divide for our purposes into three main areas: northwestern Indian tribes inhabit the first, west of the Rocky Mountains; in the second - other North American forest and steppe Indians, and in the third - South American Indians, mainly Brazilian.

In relation to life, all these peoples are on the same level of the later Stone Age. Their weapons and utensils are made of stone, bone, wood, or shells. They are engaged in farming and cattle breeding only moderately, to the extent determined by local circumstances. Weave mats and baskets are able to all the tribes of this circle of peoples; weaving art, in many places replaced by the manufacture of tapas, that is, woven fabrics softened through rubbing, is known only to some Micronesian and most American tribes; Pottery is known to Melanesians, Americans, with the exception of Northwestern Indians, and some, though a few, from Polynesians.

The architecture of this circle of peoples, much of which lives in dreamy naps and perpendicular rays of the sun, among tropical vegetation, differs in many places by massive low platforms, terraces, steep pyramids consisting of earthen mounds, cyclo-piled walls and even properly folded buildings of slabs; but in historical time, that is, since the arrival of the Europeans, the construction art of these peoples is essentially located on the pile construction stage, although in the true sense of the word pile construction exists only in one part of Melanesia, in New Guinea, and in one part of South America, Guiana

Images of animals and people here rarely attain that simple naturalness that they were able to impart to them hunting nations. But the lack of a correct understanding of nature and the ability to transmit it is usually hidden under the fantastic conventionality of style, the consistent holding of which indicates the presence of these peoples of reasonable artistic meaning. The inability to coherently portray a well-known incident is not at all everywhere, but the desire to speak for the most part takes precedence over the desire to express themselves artistically, and it goes to such an extent that the images approach figure letters, and in some places even turn into real figure letters, although they reach only its lower stage, the pictograph, transmitting the only meaning and connection of the whole phrase, the choice of words providing it to the reader.

But the unbridled artistic fantasy of these peoples is fully expressed in their decorative art. They manifest it primarily in the decoration of their bodies, coloring it, mottling scars and tattooing. In addition to decorations from the teeth of animals, shells, feathers, pieces of nacre strung on a cord, or imported glass beads, we see their use of masks during burial. The most distinctive manifestations of artistry can be considered as military and festive masks, as well as masks used in witchcraft and dances. In the decoration of utensils, boats, tools of plant images are not completely absent, but the main role is played by figures of animals and people in the most diverse and bizarre combinations or in the form of extremely amazing geometric linear combinations; regarding decorations of this kind, scientists have repeatedly come to the conclusion that, apparently, purely geometric patterns are nothing more than primitive images of animals or people, sometimes of religious significance, brought into a certain style.

The art of the inhabitants of the Pacific Islands often reflects their common religious beliefs. The polytheistic circle of legends, which developed on a pantheistic basis, has mainly the history of creation as its subject, and then inhabits the whole world and its history from time immemorial to the present day with countless gods and spirits. Spirits of stones, plants and animals can be honored with the same divine worship as spirits of dead people. Patron spirits of tribes and individuals often take the form of snakes, lizards, crocodiles and sharks. The veneration of ancestors and the cult of animals are intertwined in a very strange way.

Human figures carved out of wood or stone, common in the entire area under consideration, can be mistaken for idols or images of ancestors. Although these figures are considered vessels in which God-like spirits, souls of the dead, or parts of these souls have invaded, however, the ocean of such figures does not deify. He is far from serving the fetishes that the Negro worships, as pointed out by Weitz-Gerland.

Melanesia, the kingdom of the "black islands", received this name from its dark-skinned, kinky, Negro-like inhabitants (Papuans, Negritos), anthropologically occupying an exceptional position between other yellowish-brown or reddish-brown tribes of the Pacific circle of peoples having direct or curly hair. The most extensive island of this area is New Guinea, whose art has led to very important conclusions regarding the development of ornamentation. From the ethnographic point of view, the most important groups of islands in this area belong to Fiji Islands; but perhaps the most original manifestations of art we find in the German archipelago of Bismarck.

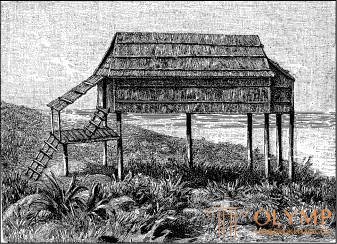

Since the temples of Melanesians do not differ from their public houses, except for a larger size, all their building art is expressed in these dwellings . The high, middle pillars, which run freely along the house, support a clearly distinguished ridge of the roof, and the lower corner pillars bear down on themselves the low sides of the sometimes-shaped roof and form a wooden or bamboo frame of the usual quadrangular structure. Light walls between the pillars are mostly made of weaving or mats. The roof is covered with palm leaves or mats. Most remarkable of all, wooden piles or beams, hewn with stone axes, are connected and attached to each other using only bindings of ropes and rattan, bast or lianas. In the north, on the coast of the bays of Gil'vinka and Humboldt, there are entire villages standing above the water. Finsh devoted a special study to the pile villages in the southeast of the island. In fig. 50 - pile construction in Annapata with roof sloping on all four sides. However, in New Guinea architecture one can notice Malay influence here and there.

Fig. 50. Pile construction in Annapata. By Finsch

Melanesians cannot be denied some ability to sculpture. Among their sculptures made of stone, the New Melklenburg (New Irish) figures carved from chalk, which can be seen in the ethnographic museums of Berlin, Munich, Hamburg and Dresden, deserve special attention. They are mostly white, only in some places slightly covered with yellow, red, sometimes blue colors and at first glance they seem to be plaster. In them, the mutual relation of body parts is wrong, the legs are too short, spherical, sometimes the cubic heads are too large. Sometimes the forehead and nose, as in prehistoric works, are on a convex surface, in comparison with which other parts of the face are recessed back. The eyes are completely round, curly hair is depicted by a network of protruding squares. Hands or symmetrically raised, or folded on the chest. The strict uniformity of both sides has not yet given way even to the frontality, according to Lange, which at least allows the members of the body to have a freer position.

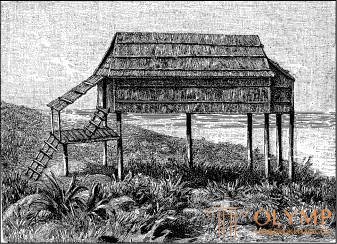

Melanesian wooden figurines, usually left unpainted, except for some protruding parts, covered with black paint, are better and more evenly executed. Among the most remarkable works of this genus are the images of ancestors from the shores of Gilwinka Bay, in the northwestern part of New Guinea, samples of which were published by Ole, the Dresden Museum. It is remarkable that these figurines, like the same “ancestor” from the British Museum, either sit behind ballet cuts, or, like the “ancestor” from the Dresden Museum (fig. 51), hold it in front of you with both hands and bring it to your mouth a similarly carved object in which Heinrich Schurz sees the remainder of the apron. It is also remarkable that the “artist”, as if knowing but mistakenly understanding Hildebrand’s view of the task of form in art, sometimes tries, as the illustrated profile drawing shows, to fit the whole figure into a given piece of wood in such a way that to touch the outer walls of the piece, prohibitively spaced from each other and connected to each other by an expressionless member extending the head. Other wood-carved objects from the coast of Gil'vinka Bay acquaint us with a peculiar Melanesian ornamentation, in which, just like in the mythological representations of the Oceanians, the images of people and animals are combined into adornments that are difficult to unravel, but generally rounded not without a sense of elegance of form. Examples of such decorations can be the ship's noses, spoon handles and amulets promulgated by Ule, in which among animal motifs one can always discern the crocodile's open mouth, while members of the human body are stretched in the form of ribbons at the ends of these objects.

Fig. 51. The figure of the ancestor from Gilwinka Bay: a - front view, b - from the side. Ole

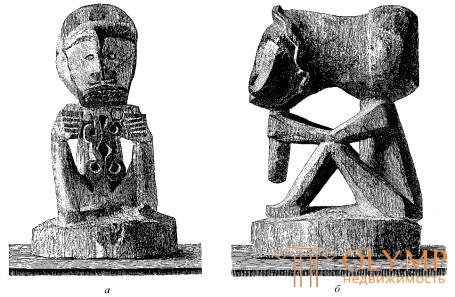

Ole was one of the first to point out that the geometric patterns of the carved and scratched works of New Guinea, predominantly the shores of Gilwinka Bay, stem from the figures of people and animals and that they have a mythological significance. The carving of these bands, similar in shape to a question mark or the letter S , to these circles touching each other and, as it were, fiery tongues, does not at first glance resemble animals and people; if, however, it is possible to discover several such figures with ribbon-like winding end members of the body inside the common pattern and notice several distinct crocodile jaws, then you come to the conclusion that distorted animal figures are really the basis of all this ornamentation. East of the Gil'vinka Bay, this ornamentation is soon replaced by another, which consists of thinner lines and which we can observe, for example, on the pivot of arrows (fig. 52), the Dresden Museum. The origin of these ornaments from images of crocodiles or lizards is undoubtedly. Therefore, both of the drawings examined by Ula are combined into one under the name "Animal ornamentation of the northwestern part of New Guinea."

Fig. 52. Animal ornamentation of the northwestern part of New Guinea. Ole

Ole's research was continued by other scientists. Alfred Gaddon, based on the London collections, divided the British part of New Guinea into five distinctly different artistic districts, and from the gradual development of human and animal figures in local art into geometric forms, he drew extremely far-reaching conclusions regarding the history of decorative art in general. Studying the German part of New Guinea (the Land of Emperor Wilhelm), K. Preiss walked the same way, who relied on a wealth of material collected in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology. It is interesting that here every district has its own art, true to its own laws of development. In Finschhafen district, plastic human figures are depicted in a squatting position. A high cap covers the head with low-hanging ear lobes, but the head is so deeply pressed into the shoulders that the quadrangular chin touches the navel. The geometric figures and ribbons embedded in pumpkins, wood, tortoise plates or bamboo and filled with black, white and red colors appear to consist of rows of dancing human figures, whose bodies are turned into ovals or rhombuses and the members in angular patterns. Crosses are formed from the eyes and nose. Bird heads turn in trapezium, semicircles, triangles and spiral appendages. In the Astrolabe Bay district, the plastic figures of the people crouched have a different type. On their head, perhaps for the designation of hair, there is a tire in the form of a plate; the face is long, the chin is not angular, but sharp; instead of the eyes, rectangular bulges peek out from under the convex forehead. Linear ornamentation is more angular than in Finschhafen. At various transitional stages of the transformation of human figures into an ornament, one can trace how little by little the head disappears, the body turns into a rhombus, arms and legs - into straight lines touching each other at angles. In the area of the north bank, plastic human figures are usually presented in a standing position, with their arms raised up. The ears are normal, and the nose is sometimes elongated like a beak. The linear ornamentation of this area is particularly rich, and in it one can clearly distinguish such patterns, which, scanty in their forms, modified and arranged in rows, turn into geometric patterns. These samples are limited to the figures of squatting and dancing people, human faces and their parts, flying dogs, fish, snakes and lizards. “All these objects of the image,” Preis said, “experienced such a transformation into simple lines, that the study of the development of these lines for the study of ornamentation was generally extremely fruitful, especially since the results delivered by completely different samples are very close to each other.” For example, the rounded strip of the meander, apparently, occur sometimes from dancing people, sometimes from flying dogs. Such a transformation is not subject to denial, since there are all its intermediate stages. Most of these patterns, moreover, are dismembered so strangely and diversely that they cannot be imagined without assuming a special kind of starting points for them. But the native artist, who deals with simple schematic patterns, zigzag lines, and even with meridric drawings, is not always aware of their origin. The established derivation of identical simple geometric patterns from the forms of various living beings in itself shows that the patterns, already independent of these forms, are inherent in the fantasy of the draftsman, so that, strictly speaking, all the above-mentioned images of the organic world are gradually woven into geometric patterns.

On the Bismarck archipelago, especially on the island of New Mecklenburg, wood carving, representing a combination of human and animal motifs, takes such strange, fantastic forms that, by originality, has nothing like itself in the whole world, among all branches of artistic and craft industries. Once you see patterns of this thread, you can not get rid of them, as from a nightmare. They feel the pressure of burning tropical heat on the fantasy of the person who created them. Уже одна окраска придает им особенный характер: они иллюминированы черным, белым и красным цветами, к которым изредка прибавляется немного желтого и (привозного) синего. Но оригинальность этих фигур заключается главным образом в их мотивах, которые представляют хватающих друг друга с открытой пастью и снова отпускающих друг друга людей и животных, и в искусной сквозной, напоминающей плетение из прутьев работе этих свойственных каменному веку резных украшений, которые мы встречаем на щипцовых балках и дверных косяках, танцевальных масках, амулетах – словом, везде, где только есть возможность что-нибудь изобразить и вырезать. Ядром, которое окружено всем этим решетчатым нагромождением, служит обычно человеческая фигура, но иногда его составляют разные фигуры, касающиеся друг друга во всех возможных и невозможных положениях. Нередко главной фигурой являются рыба, ящерица и петух, а чаще всего – птица-носорог, которую океанийцы считают священной птицей мертвых. Глаза обычно состоят из вставленных раковин и иногда играют в композиции самостоятельную роль, независимую от человеческих лиц и голов животных. Каждое произведение задает нам новую загадку. Генрих Шурц предложил весьма убедительное мифологическое толкование этих произведений. Уже по самому своему существу культ предков связан с представлением генеалогического дерева, со стремлением изображать их рядами и приводить в связь между собой; культ же животных, тесно связанный с почитанием предков, побуждает в таких изображениях чередовать предков-животных с предками-людьми. Но весь этот двойной культ умерших обусловливается представлениями о загробной жизни. Корабль, увозящий души умерших в загробный мир, заменяется птицей мертвых, как только люди начинают предполагать существование этого мира за облаками, а не на далеких островах; птицей же мертвых во всей малайско-меланезийско-полинезийской области считается преимущественно птица-носорог. Открытая пасть животного, из которой выставляется человеческая фигура, обозначает символически не поглощение, а тесную связь, произрастание одного создания из другого.

In Germany, the ethnographic museums of Berlin, Dresden, Munich and Hamburg are rich in works just reviewed.

In fig. 53 - carved product, which is a human figure, combined from shells crabs, Berlin Museum.

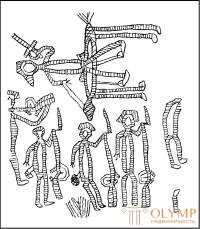

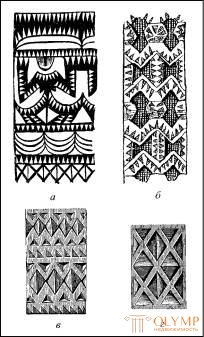

Scratched drawings and their interpretation should be sought in the Melanesian region and outside of New Guinea. Scrawled and blackened drawings, a kind of hieroglyphic writing, we find mainly on bamboo canes and sticks, such as, for example, blacks in "Melanesian Diasiora" (according to Ratzel), on the Malayka peninsula, and among the inhabitants of New Caledonia (Fig. 54) and New Hebrides. Steveres and Grunwedel are found at Malakan Negritos (Orang-Gutan, Orang-Semang) drawings, scratched and charcoal-blackened on charcoal on women's bamboo crests, on bamboo quivers, pipes and wands of men, which we see in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology. Patterns consist of obviously geometrical figures - from corners, triangles, quadrangles, circles, zigzag lines; but upon closer inspection, these drawings turn out to be stylized and abbreviated representations of miraculous animals and objects, for example, zigzag lines signify frog legs, the same last ones — whole frogs pointing to the marsh where they live. Together, these signs constitute magical formulas that have the power to protect carriers of objects on which they are inscribed from diseases and all dangers. Each danger has its own specific formula, each formula has its own special pattern. Something similar exists in the negritos of the Philippine Islands, as evidenced by the crests of the Dresden Museum.

Fig. 54. Drawing on Novokedledonskoy bamboo canes. From the original of the Dresden Museum of Ethnography

Compared to wild Melanesians, who still have cannibalism, Micronesians and Polynesians, taken together, make up a monotonous tribe, if not in all respects more cultured and rich, then in any case more gentle and reasonable.

The Micronesians , in general, give the impression of a small people descending from the once higher level of culture. "A light whiff of historical life," said Ratzel, "melancholically wraps around their villages and lonely ramparts on the hills, now made redundant."

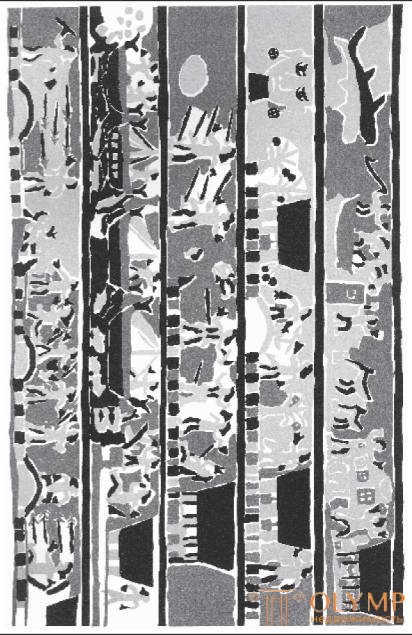

Finsch, on the contrary, spoke repeatedly about the prehistoric buildings of this group of islands. The unknown history of these peoples, which for some time have been under the protection of the German Empire, seems to us prehistoric. Mainly on the Karolinsky Islands, for example, on the island of Lella (Leyley), which was once the residence of the people's leader, near Kushai (Kuzaye), and on a small basalt island near Ponape, huge walls survived, partly composed of basalt pillars placed longitudinally, like wooden logs ; these walls owe their origin to the aggregate labor of long-vanished generations. The stone lower parts of the buildings, to a limited extent suitable for these historical or prehistoric remains, constitute one of the features in the dwellings of the current generation of Micronesians — dwellings, which, however, are different in the group of islands. For example, in the Karolinsky islands, the supporting pillars are always hewn, the roofs are distinguished by high, narrow, sometimes painted gables, between which the roof ridge, dropping down in the middle, gives it a saddle look. In the Palau Islands, the crest is straightforward, but at the gables it comes out somewhat to protect the images painted on them. Especially luxuriously decorated large houses serving as meetings, so to speak city hall. The picturesque and plastic decorations on the gables and beams of the main houses in the Palau Islands belong to the most outstanding works of art in Micronesia. In the middle of the pediment there is usually a plastic, yellow-colored female figure, distinguished by more pure and rounded shapes than those we saw in Melanesians. The rest of the pediment is painted with red, yellow and black colors, and inside large dissecting lines are placed objects and signs, among which the main role is played by sockets like sunflower and naturally transmitted sea fish, located near several rows of small acting human figures. The beams inside the houses are completely covered with long images like friezes or belts. The drawings are partly embedded in raw wood and rubbed with a white mass, partly painted on the plane with black, red and yellow paints. In the Dresden Museum there are two such beams, brought by Semper from the Palau Islands and made public by Adolf Bernhard Meyer, as well as color shots of a number of other beams. In fig. 55 - a series of individual beams (pushed lithographer to one another). Like all the narrative series of images, the drawings seem to have partly the character of figured writing, the meaning of which, of course, can only be understood by acquaintance with the entire cycle of legends and legends of the Palau Islands. But in reality it is on a small scale monumental images of incidents, and for the initiated, this pictorial way of narration leaves nothing to be willing in terms of liveliness and comprehensibility. We recognize here canoeing, dancing, battles, whale-fishing scenes. Everywhere one can distinguish houses with their stone lower parts and protruding gables, palm groves everywhere are distinguished, and the sea can be recognized by shuttles and fish. Human figures are presented ineptly, in the form of silhouettes, mostly in profile, but they are distinguished by quite lively mobility. The well-known rhythm and uniformity give all the ranks, taken together, the proper decorative frisiform character.

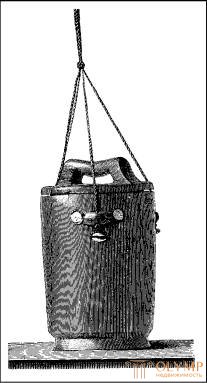

As a feature of the Micronesian one should, in addition, point to the ancient Palauan wooden vessels and utensils with mother-of-pearl inlay. White carved shell pieces stand out nicely on a dark red painted wooden background. Inlays have partly the appearance of triangles, which are sometimes arranged in rows, like leaves sitting on petioles, and sometimes form rows of geometric figures, bird figures or even warriors, as can be seen, for example, on a Palauan vessel with a lid stored in the British Museum. Of these products, the hanging vessel is especially remarkable (fig. 56); his vertically pierced handles seem to be noses, two mother-of-pearl mugs placed on both sides are his eyes, and planted under cowry cup with a hole is his mouth. Obviously, such a result was obtained intentionally, and such vessels adjoin the original urn-owned urn with faces found on the Danish islands.

If not in the fullest, then in the most pure form Oceanian culture we can observe in Polynesia. The myth-rich Polynesian religion, which worships Tangaroah as the creator of worlds and the highest heavenly god, is the source and guardian of all mythological ideas of the Oceanians; Polynesian history, in the center of which are legends about wandering in immemorial times, preserved among the population of the central groups of islands, especially Tonga, Samoa and Tahiti, New Zealand in the extreme south and the Sandwich Islands in the extreme north, reached us in the form of remnants of ancient structures, mainly in the form of massive, cyclopically folded concessions, which to this day serve as the foundations on which Polynesian "temples" and dwellings are erected.

Fig. 55. Painted bars houses in the Palau Islands. According to Karl Zemper and from the original of the Dresden Museum of Ethnography

But neither these temples, consisting only of fenced sacred spaces with scenes, idols of gods and altars, nor spacious Polynesian dwellings and public houses, are not at all or almost no better than Micronesian buildings of this kind and do not represent a further step in the development of architecture. Only in New Zealand are visible successes of this art, due to the local climate. Here, houses often consist of sturdy plank walls, and local carpentry, even before the arrival of Europeans, developed so much that it has already reached the real nailing of the boards to each other and putting them into one another, instead of using the binding of pillars and beams into Central Polynesia .

But neither these temples, consisting only of fenced sacred spaces with scenes, idols of gods and altars, nor spacious Polynesian dwellings and public houses, are not at all or almost no better than Micronesian buildings of this kind and do not represent a further step in the development of architecture. Only in New Zealand are visible successes of this art, due to the local climate. Here, houses often consist of sturdy plank walls, and local carpentry, even before the arrival of Europeans, developed so much that it has already reached the real nailing of the boards to each other and putting them into one another, instead of using the binding of pillars and beams into Central Polynesia .

Fig. 56. Ancient Palauan hanging vessel. From the original of the Dresden Museum of Ethnography

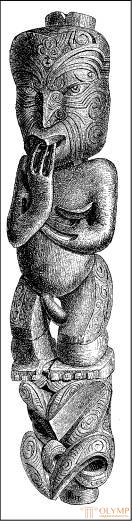

In Polynesian sculpture, or, strictly speaking, wood carving, we meet more often than in Melanesian art, human figures, which, due to the religiosity of the Polynesians, should be recognized as the depiction of the gods, and in these images of the gods we often find right next to naive attempts to convey human appearance, deliberate distortion for the sake of mythological ideas. Of the Polynesian idols of the London Missionary Society, recently transferred to the British Museum, such a deliberately distorted mythological image belongs to the round figure of Tangaroa, which, for all its clumsy naturalness, navel, nose, eyes, ears, nipples, breasts, etc., consist of idols children's figures. The plastic of the New Zealanders is characterized by a male figure with a right hand attached to the mouth (in the Christie’s London collection, fig. 57). Her short legs and big head resemble the Melanesian figures of ancestors, but strict symmetry is replaced in her by the frontality (according to Julius Lange), since her arms are folded more freely. Body shapes and especially facial features are softer and rounder than those of Melanesian figures. The face itself is proportional. The eyes, mouth and nose are natural and proportionate. The face is artfully tattooed with spiral features, like those of New Zealanders. It is remarkable that here, as in all works of New Zealand art, we find on the hand only three fingers, which testifies to the inability to count. A peculiar combination of human forms can be seen in the idol from the islands of Hervey, the Munich collection. Under the big pointed head, flattened from the sides, on each side is placed a crippled, jagged back hand with three fingers, and the torso is made up of six small, crouching human figures with splayed legs, and these figures are adjacent to each other in a continuous row, alternately looking in front and side. If such works express the same mythological fantasy as in the Melanesian carvings of New Mecklenburg, then it must be admitted that here this fantasy is expressed more simply and more strictly.

Fig. 57. New Zealand figure. According to Ratzel

Images of this kind are very important for explaining Polynesian ornamentation. Based on the female figures depicted in flat carvings on decorative sacred axes, sacred oars and drums found on the Hervey Islands, Reed and Stolpe tried to explain the origin of a whole class of geometric linear ornaments of these islands from the stylization of these figures and, therefore, not only recognize all this ornamentation, consisting of countless figures of goddesses, but also to see in it the expression of religious-symbolic representations, very related to those that we find among Melanesians. These ornaments are presented in Fig. 58: a - on the handle of the oar (Hamburg Museum); b - on the handle of the bucket (Basel Museum); in - on the wide part of the paddle; Mr. - on the ax ax butt (Stockholm antiquarium). This kind of attempt to explain, of course, should not be generalized, since they can even lead to opposite conclusions from relatively neighboring areas. In addition to the region of Rarotonga-Tubuay-Tahiti, Stolpe himself, from where the example is taken, recognizes in Polynesia a number of other provinces that are important for ornamental art. In the province of Tonga-Samoa, for example, straight and zigzag lines dominate, sometimes incident on each other, but leaving room for figures of people and animals planted between them. In the province of Maori (New Zealand), ornamentation consists of curved lines, for the most part even from fully developed spiral lines, which, thanks to the conch-eyes that are often among them, sometimes take on a distorted look of a human face.

Fig. 58. Ornaments of the Hervey Islands. According to Stolpe

Finally, a special cultural region of Polynesia is Easter Island, which lies in the extreme east of this mass of islands. Since the reports of Geisler and Thompson, we can form a clear concept of the peculiar art of this separate world, inhabited by only 150 souls. Of the architectural works of this island, we are primarily struck by the small stone houses of sculptors, without windows, covered with stone transverse beams, near the crater of Mount Rana-Rorac, and the house of egg-gatherers of gulls on the slope of Ranakao facing the sea. Both in that and in another place the storms would demolish the wooden huts. And here, it means that one can see to what extent inventive need is. Waiting for seabirds on the slope of Ranacao, young people whiled away the time and had fun with various artistic exercises: they carved out plastic figures on rocks or on door pillars in the form of half-reliefs, grind limestone plates with red, black and white colors inside the buildings and covered them with different images. The main content of these sculptures and paintings is the semi-animal-half-human gods, mainly the figure of the keeper of the eggs of seabirds, the great sea god Meke-Meke with the beak of a seagull. These works of art can be studied mainly in American museums.

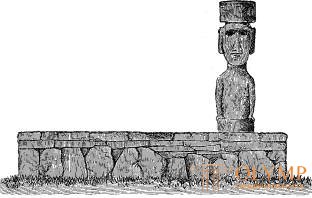

Fig. 59. Platform with a stone figure on Easter Island. By thompson

On all the shores of the island, the ruins of the former dwellings are preserved and next to them are not the temples themselves, but the large stone platforms on which the statues of the ancestors were placed are in connection with the stone tombs, sometimes giving the impression of dolmens. Something similar we find on all the Pacific Islands, but the peculiarity of Easter buildings is that the platforms are found very often, have unusual proportions, are original because of the large size of the colossal stone sculptures hoisted on them, the production secret of which was inherited. Now, none of these statues stand straight; in most cases they lie in a more or less well-preserved form on or near their supports. Thompson described 113 similar platforms; the most enormous of them is the Tongariki platform under Rana-Rorac, reaching 160 meters in length with its wings. The same traveler counted on the small island at least 555 stone statues of the above kind. The smallest of them - height less than 1 meter, the largest reaches 21 meters. It is remarkable that these statues represent only half-figures with huge heads. Hands or not at all, or they are only marked with flat relief on the body. The heads behind are usually cut off, and the front is characteristically treated, all of them differing with huge ears, low protruding forehead, cheekbones and long cheeks, a long, inwardly curved nose, thick nostrils and thin, squeezed, but somewhat prominent

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)