Architecture

The style of the French early Gothic, still imbued with the Romanesque spirit, is found in southern Germany (the Rhine region we leave aside) in the architecture of the Bamberg Cathedral (see fig. 222), whose western towers are copied, not without misunderstanding, from the towers of the Lyon Cathedral. The first church that emerged after 1250, surrounded on all four sides by aisles with empores, is the church of Sts. Ulrich in Regensburg - gives the impression of Gothic only with its individual forms. On the contrary, the gothic design is a slender longitudinal body of the church of St.. Sebald (Sebalduskirche) in Nuremberg, belonging to the second half of the XIII century. Built a century later, the high and vast eastern chorus of the hall system, attached to this somewhat squat longitudinal hull typical of the basilica, is majestic but dry in details (for example, its service columns are devoid of capitals) - a typical late Gothic building.

In southern Germany, as in the Rhineland, the church of mendicant orders, by applying Gothic laws, greatly simplified them. Some of these churches, such as the Minorite churches in Regensburg and Würzburg, built in the second half of the 13th century, despite the Gothic style of individual forms, are flat-capped basalic basilica; other churches, such as the Dominican Church in Regensburg and Eslingen, received the Gothic system of vaults, but without supporting arches.

The first large Gothic cathedral in the full sense in the Danube countries was the Regensburg Cathedral, a building begun by construction at the latest in 1275 according to South French designs. These samples were the church of the Virgin and of sv. Benignas in Dijon, so different from each other (see Fig. 355). The construction began with a choir; the construction of the longitudinal hull continued throughout the fourteenth century; The western part of the church with its trilateral porch belongs to the XVI century. Two beautiful openwork towers were completed only in the second half of the XIX century. The interior of this three-nave basilica, the transept of which does not protrude, is spacious and nobly simple, but its individual forms are neither fresh nor elegant. The last basilica of Nuremberg is the church of Sts. Lawrence (Lorenzkirche), the longitudinal body of which, begun with construction in the second half of the 13th century, belongs in its main parts of the 14th century, while the choir was rebuilt only in the 15th century.

From the middle of the 14th century, the hall system prevailed throughout Austria, Swabia and Bavaria. In Bohemia, already in the late 13th and early 13th centuries, hall churches were built; such are, for example, the church of sv. Bartholomew in Kolina and the Church of Sts. Aegis in Prague. In Austria, the first building of this genus was the magnificent choir of the church in Heiligenkreuts (built in 1295), followed by the Augustinian church in Vienna, founded in 1330, with a strongly elongated temple, octagonal pillars, which are arranged with round service columns. Already in 1340 the choir of the famous Cathedral of Sts. Stefan, surrounded by a simple walk. A longitudinal hull without a transept is lined with richly dissected pillars and covered with mesh arches; it has lateral aisles of almost the same width, but only approximately of the same height as the middle aisle. This retreat from the strictly hall system fills it with a mysterious twilight and, with the magnificence of individual forms, makes it one of the most spectacular church premises. The slender pyramidal tower (one of the tallest bell towers in the world), completed only in 1433, takes the place of the south wing of the transept; the fact that the north tower was never completed is less detrimental to the overall impression of the view of the cathedral than the absence of a second facade tower in Strasbourg and Antwerp. To the north-west of Vienna, in Cvetla, the Cistercian church was built in 1343, the chorus system of which for the first time represents the peculiarity that it has a larger number of sides on the outside than on the inside (but the inner sides, respectively, are longer): closes seven sides of the 16-gon, the chorus itself - five sides of the octagon; the crown of the lower chapels adjoins the high choral circuit. Here a step has been taken towards the unification of parts of the church premises.

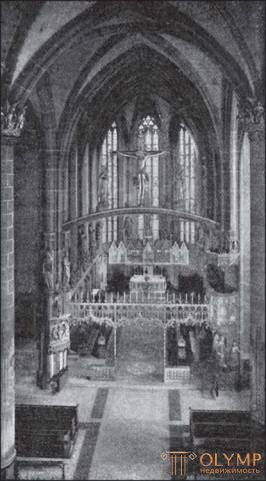

Fig. 277. The interior of the Church of Our Lady in Nuremberg. From photos of Schmidt

The same system is found in Swabia. The Church of the Holy Cross in Schwäbisch Gmünde is a hall church with a hall choir (1351), which, like the church of Tsvetl, has a low crown of chapels and an unequal number of sides of the outer and inner endings of the choir. Slender round pillars, decorated with low leafy capitals, support highly branched mesh arches. The builder of this church is Heinrich Parler, the founder of the famous architects. The assumption that he was from Cologne is not proven, but has many grounds. The opinion that Parler borrowed the plan of his Gmünd church from Tsvetl found a skilled defender in the person of Degio, who saw here the first example of the “reverse action” of the Gothic style, from east to west, and a no less skilled opponent in the person of Bach. Be that as it may, this huge church, the construction of which was completed only in 1414, became a model for the Swabian countryside. With its simpler choir form, its architecture is imitated by the graceful church of Our Lady of Esslingen, which began construction in the middle of the 14th century and completed by the best craftsmen of the 14th century. The first Nuremberg hall church, erected on a square base and decorated with a pediment that resembles civilian Gothic buildings, the Church of Our Lady (Liebfrauenkirche), built since 1355 (fig. 277), as well as the first hall structure in Würzburg - the chapel has a slightly different character. Mary, outside adorned with luxurious, but already monotonous Gothic ornament.

Then follows the cathedral in Ulm. Initially (1377), it was designed as a hall church, and, according to Bach, during the first period of its construction, none other than Heinrich Parler from Gmünd and his son Michael managed the construction, but when the building passed into the hands of Ulrich von Enzingen ( 1392), the majestic temple was turned into a five-nave basilica, which belongs to the XV century.

Outside of common development, a 12-coal round monastic church in Ettal, in the Bavarian Alps, should be established. Overlapped initially by one large costal vault ("monastic" or "boiler room"), it was subsequently backed in the middle by a column and remade in the Baroque style. It is believed that the emperor Ludwig of Bavaria, founding this church (1330), wanted to create a free imitation of the church of Sts. The Grail in Wolfram von Eschenbach's Titeurel.

Of considerable historical and artistic interest is the further evolution of church architecture in Bohemia, the birthplace of Emperor Charles IV (1347–1378), who rebuilt the ancient cathedral of Sts. Vita on the heights of Hradcany (Hrad Cany) in Prague. To create a real Gothic temple, Karl, before he became king, called (1344) North French architect Matthias of Arras. The architect took the Narbonne Cathedral as a model and designed the magnificent basilica, whose round choir with a roundabout and crown of chapels was completed only in its lower parts, when the master died (1352). Then, to continue the grand construction, the Swabian architect Peter Parler, one of Heinrich's sons, was drafted from Gmünd. His inscription at the Prague Cathedral, in which his name is incorrectly read “Arler”, became the source of the “whole Parler question” in science, over which Karstanjen, Neuivirt, Gurlitt, Dégio and Bach were involved in ascertaining. Peter Parler, who led the construction of the Prague Cathedral before 1392, graduated from the entire choir and laid in place of the south wing of the transept, modeled on the cathedral of St. Stephen's in Vienna, a huge tower, completed later. Multiplying the number of outer buttresses, Peter imitated Cologne Cathedral. The chorus, with its service columns, which are partly devoid of capitals, partly equipped with leafless capitals, represents, for all the grandeur of its proportions, a typical piece of doctrinal, eclectic Gothic. Later Peter Parler endowed the hall church of St.. Bartholomew in Colin choir, whose low aisles have a flat roof. This church gives the impression of insufficient organicity, as well as the church of Sts. The barbarians in Kuttenberg, whose numerous counterprofors, completely seated with turrets and ornamental motifs, as well as the supporting arches, are apparently designed for an artistic effect. According to Neivirt and Gänel, the Karlhof Church in Prague, founded in 1351, should also be attributed to Peter Parler, in the opinion of Degio, the school of this master. Its nave has an octagonal shape; Above it rises a huge domed gothic vault, fortified with supports. The aforementioned monastery church in Ettal served as the prototype of this church, and according to legend - the Cathedral of Aachen. We see that South German and Austrian church architecture was often able to independently apply the Gothic forms borrowed from outside.

The development of secular architecture in many respects proceeded in parallel with the development of this type of art on the Rhine. The Gothic Town Hall in Nuremberg was built between 1332 and 1340. and, as proved by Essenwein, by the same plans as the old town halls in Cologne and Mainz. A partly preserved large hall of the upper floor in the Nuremberg Town Hall has horik, or a ledge in the form of a lantern, between two windows with openwork, patterned bindings; in the gable, which was provided outside with a luxurious vertical finish, phials and a machine for the bells, placed a large round window. The Nuremberg apartment house style feature is the Nassau or Schusselfeld house, an exemplary example of residential towers (a genus of small fortresses) of that time, with wall battlements and corner turrets, which are interconnected by a gallery with luxuriously decorated choirs and - at the very top floor - with straight bounded at the top of the windows. The most beautiful choir was formerly on the church house at the church of St.. Sebald in Nuremberg (see Fig. 279). The Town Hall of the Old Town in Prague (1336) can also be considered a magnificent building of the fourteenth century; it is especially remarkable for the choir of its chapel and the tower, which, however, was added only in the 15th century. From a similar 14th-century Krakow Town Hall, only the tower, towering on the Market Square, not far from the “cloth rows” rebuilt many times, survived. Everywhere it is clear that this Slavic west is becoming the eastern province of German art. As for the architecture of the castles, the most significant monuments are preserved only in the east of the German Empire. It is necessary to point primarily to the fortified castle of Karlštejn, built on a steep rocky mountain in the wooded surroundings of Prague for the emperor Charles IV by the architect of Prague Cathedral Matthias of Arras. This castle, which began construction in 1348, is a group of various structures, the lower floors of which are covered with box-shaped star-shaped vaults, while the upper rooms have flat wooden ceilings. Then it is necessary to mention the Wajda-Gunyad castle in the vicinity of Hermanstadt (Hungary) - the fortified building of the hall system, dating back to the end of the XIV century. The upper main hall of this castle, supported by five round pillars, consists of 12 compartments covered with cross vaults. A gallery stretches along its outer side, from which four gracefully decorated horikas, which have half a pentagon in plan, protrude forward. From our review it is clear that Austria and Hungary in the era under consideration are already entering the circle of Western European art.

Plastics

In Southern Germany, as in the Rhineland, the Gothic monumental plastics penetrated in connection with the Gothic church architecture. Depending on whether it penetrated directly or by district routes from France, whether it relied on the more ancient German tradition or lay on the virgin soil in artistic terms, whether real artists or stonecutters worked on it, even here it created different meanings and artistic values. Hardly at least one church building was completely devoid of sculptural decoration, but even sculptures of such significant architectural monuments as Regensburg Cathedral or the Cathedral of Sts. Stefan in Vienna, have no particular artistic significance. The first place in the development of South German plastics belongs to the Frankish school. The best monuments of the South German plastics of this era should be considered later sculptures of the Bamberg Cathedral, which have been written about so much and which probably belong to the third quarter of the 13th century. The style of these sculptures, known to us since the advent of the studies of Degio and Vase, penetrated the shortest way from France; but at the same time, as Goldschmidt, Frank, and Föge proved, it developed on the basis of the Old Frankish style, so fully represented by the early sculptures of the same Bamberg Cathedral (see Fig. 225). Undoubtedly, one of the masters of the Bamberg workshop worked in Reims and borrowed from there artistic finds that were reworked and developed, and so a new, German style was born, sometimes giving way to its original form in purity and beauty of forms, but often surpassing its power and inner life . Already in the previously described Last Judgment at the Princes' Doors of the Bamberg Cathedral, Föge indicated a number of Reims elements; Vaeze emphasized the Reims features in all the main figures who later emerged from under the chisel of the chief master of the Bamberg cathedral. These include, above all, the figures of the Church and the Synagogue (Fig. 278) on the Princely doors. Compared with the Reims samples, they are not only independent, but also refined works of very lively and sensitive art. Recall the 6 large figures on the side walls of the southern portal, near the eastern choir: Adam and Eve, Peter and Stephen, Emperor Henry II and his spouse Kunigunda. The nakedness of the progenitors is unknown to the plastic of the Reims Cathedral, the image of the first people without covers in the round plastic is due to the Bamberg master; these naked bodies are still strict, long and narrow, mannered and meaningless, but their proportions are generally found correctly. The ideal, dignified figures are the statues of the emperor and empress; however, they resemble classic Reims male figures with the head of Odysseus and the Queen of Sheba; but already the head of sv. Kunigunda represents the completely individual style of the Bamberg master. These statues by their features also belong to the brilliant works of medieval German art. Inside the cathedral, our eyes are fascinated by the rider in the crown, standing on the left (north) pillar of the eastern choir. Usually they see the image of Conrad III in it. Awkward, ugly horse, not having a prototype in Reims, apparently made from nature; the head of the emperor facing forward in a noble movement resembles the heads of kings depicted in the Cathedral of Reims; but the whole of the sculpture represents again the German work of art with a bright imprint of an individual manner. Further, it should be noted the large statues in a roundabout of the eastern choir, and above all the figures of Mary and Elizabeth, which make up the Visiting group. They are strikingly close to the familiar figures of the "Visit" in Reims Cathedral (see Fig. 249). In strength and greatness, they have almost no equal. Finally, for a portrait with dignity of an aged image of the pope, located opposite these statues, the sample can be indicated in one of the papal portraits of the Reims facade. Bamberg relief depicts Pope Clement II. Initially, the relief was placed as a cover on a sarcophagus, decorated with luxurious elegant style reliefs, which now stands in the choir of St. Peter (western). This sarcophagus is undoubtedly the work of the same master. Truly, the artist who performed it is an artist whom Germany can proudly call her. However, the statue of the Madonna of Bamberg Cathedral and the curious figure of Queen Kunigunda of the early 13th century, curious in its preserved coloring, show us how gradually this style gives way to the more mannered style of the 14th century. But even in these figures, the Gothic bend is unusual for them.

Fig. 278. Synagogue. Statue on the Princely doors of the cathedral in Bamberg. According to the pictures of Haath

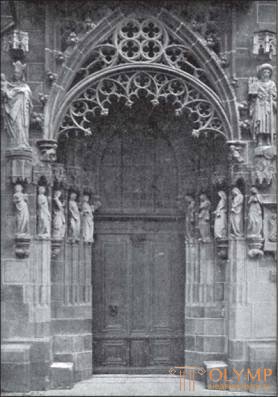

Fig. 279. Doors of brides in the church of st. Sebald in Nuremberg. From photos of Schmidt

Staying within the francs, we can observe the further development of plastics in the direction of greater realism throughout the XIV century, mainly in Nuremberg, whose prosperity begins just from that time.

Already, Bode saw in this development a “continuous preparation for the Renaissance of the 15th century.” Until the middle of the XIV century, the Nuremberg plastics followed foreign models. From the same time, a special Nuremberg style began to be developed.

Несмотря на отсутствие широты в замысле и мещанское направление, новое чувство, начинающее преобладать в этом стиле, сообщает ему силу и прелесть. В стиле первой половины XIV столетия выполнен Страшный Суд на южном боковом портале церкви св. Зебальда, композиция которого заимствована с северного портала Бамбергского собора. Около середины этого столетия возникли знаменитые Двери невест, ведущие в притвор северного нефа восточного хора (рис. 279). Кружевная ажурная резьба наружной арки этого портала, подле которой стоят статуи Богоматери и св. Зебальда, отличается в одно и то же время богатством и изяществом. Скульптурное убранство Дверей невест напоминает скульптуры притвора Фрейбургского собора. Статуи мудрых и неразумных дев на наружных боковых стенках портала отличаются осмысленным и ясно выраженным готическим изгибом, в то время как статуи Адама и Евы, помещенные внутри притвора, под бюстом Спасителя, принимают уже более прямую, но вместе с тем более суровую позу. Между 1350 и 1380 гг., по определению графа Пюклера-Лимпурга, основательно исследовавшего нюрнбергскую пластику с 1350 до 1400 г., возник главный портал церкви св. Лаврентия, скульптурное убранство которого, очень искусно распределенное, но несколько ремесленно выполненное, заканчивается в тимпане опять-таки изображением Страшного Суда. Интересны четыре рельефа в нижних полях обоих тимпанов с изображением детства Спасителя. Из статуй, расположенных на стенах, Адам и Ева представляют шаг назад по сравнению с подобными же статуями бамбергского мастера. Тем не менее здесь все же можно подметить новые черты стиля, ведущие свое начало, по-видимому, от скульптур среднего портала Страсбурского собора (см. рис. 272). Мастера, работавшего над порталом св. Лаврентия, превосходит другой художник, изваявший внутри церкви св. Лаврентия статуарную группу «Поклонение волхвов» со стоящей Богоматерью. Дальнейшее развитие форм представляют уже 5 рельефов на возникшем после 1361 г. хорике церковно-приходского дома при церкви св. Зебальда, позже перенесенном в Германский музей, с изображением Благовещения, Рождества Христова, Поклонения волхвов, Успения и Небесного Коронования Богородицы. В этих рельефах немало отдельных новых черт. Еще свободнее по стилю более поздние изображения Успения и Коронования Марии в тимпане северного бокового портала церкви св. Зебальда.

The heyday of the late Gothic Nuremberg plastics (1380–1400) is represented by the school of clay sculptures and the master who made the work “The Fine Well”. Of the Nuremberg clay sculptures to the earliest belong painted painted statues of the Savior and the Apostles in the church of Calchreith, near Nuremberg. Despite the general severity of posture, the coarse technique of some parts of the body, such as hands, they show a striving for originality, manifested, for example, in the curls of the apostles' hair, treated independently of the head and falling on the forehead. The master, who fulfilled the Nuremberg apostles, discovers a higher, more free degree of development, of which six have entered the German Museum, and four adorn the church of Sts. Jacob (Jacobskirche) in Nuremberg, while the two statues of the Magi, worshiping Christ, in the Berlin Museum, apparently, earlier works of this sculptor. Above in skill - the creator of the Gothic fountain "Beautiful Well", set at the end of the XIV century in the square, in the corner. The peaked column towering above the octagonal basin has the shape of a slender Gothic church pyramidal tower and is decorated with exquisite openwork carvings. The statues of heroes and saints that were here before were later replaced by copies. By fragments of originals in the German and Berlin museums, you can recognize the style of two different sculptors. Eight figures of the prophets of the upper row, half the full size, from which three heads are in the Berlin Museum, three torsos - in the German Museum of Nuremberg, expose the hand of the still timid, but already striving for the artist as possible to the full vitality. Of the 16 statues of the heroes of the lower row, whose fragments are in the German Museum, the best, such as the figure of the Elector of Trier, combine the greatness of bearing with such expressiveness of animated faces that we rank them as masterpieces of German art. Finally, the magnificent equestrian statue of Sts. George in the Berlin Museum, giving us an idea about the state of Nuremberg art around 1400

In contrast to the Frankish school of sculptors, the Swabian school of the fourteenth century. followed a direction filled with greater depth of feelings, but at the same time weaker. This is shown, for example, by the rich sculptural decoration of the main facade of the Ulm Cathedral in the middle of the XIV century, as well as statues and reliefs of the portal of the Augsburg Cathedral, whose stylistic differences among themselves were indicated by Walter Joseph, and later and therefore more realistic sculptures on the portals of the Church of the Holy Cross in Gmünd, whom Bode called "the true plastic illustration of the Christian doctrine of salvation."

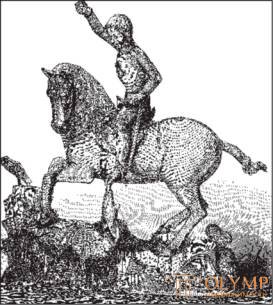

We could have expected that Bohemia, whose art flourished so quickly during the reign of Charles IV, was not left behind either in the field of sculpture. However, it is surprising that an interesting, unfortunately mutilated, statue of St. Wenceslaus in Prague Cathedral according to his inscription turns out to be the work of the builder of the cathedral Peter Parler from Gmünd; it is also surprising that the style of the magnificent bronze statue of St. John of God cannot be determined. George, striking a dragon, which is located in the courtyard of the castle in Prague (Fig. 280). This one-of-a-kind piece of goldsmithing of craftsmanship, performed in half a life-size, is realistic, expressive and energetic, and, according to the inscription, must be attributed to the works of brothers Martin and Georg von Klussenbach (or Klussenberg), by the time before 1373. Compared with the Italian equestrian statues of the 15th century, this statue is still somewhat dry and timid in its technique, but surpasses most of the similar sculptures of the 14th century with the immediacy of observing nat ury, both in the forms and in the motives of the movements of the horse, rider and dragon.

Fig. 280. Equestrian statue of sv. George in Prague. By bode

Tombstone portrait sculptures, of course, are also frequent in this era in southern Germany and Austria. The Burgundian influences reflect the tombstone of Konrad Gross in about 1380 in the hospital church in Nuremberg. Eight backwaters supporting, like the legs of the table, a marble slab, under which the figure of the deceased rests, are seated figures of mourners and mourners, living in poses, but sluggish in technique and not entirely successful in transferring borrowed motifs. Some tombstones are collected in the German Museum in Nuremberg and in the National Museum in Munich. They are preserved in the greatest number, partly with obvious traces of coloring, in the church of Sts. Emmerama (Emmeramskirche) in Regensburg and Würzburg Cathedral. In the church of sv. Emmeram's some distinguished portrait sculptures, such as Emperor Henry IX and the two empresses, belong only to the middle of the fourteenth century; in the Würzburg Cathedral, the gravestone sculptures of the bishops Manegold von Neuberg (d. 1302), Otto von Wolfskel (d. 1345) and Albert von Hohenlohe (d. 1372) with significant portrait similarity differ with the mannerism pos. The desire for beauty is again manifested in the monument to Bishop Gergard von Schwarzberg (died in 1400).

Painting

The direction in which painting develops (1250-1400) is the same everywhere; However, in different countries, these parallel paths of development often open up different horizons for us. In the area encompassing Württemberg, Bavaria and Austria, painting, although it did not develop as consistently and independently as on the Rhine, for example in the Cologne school, nevertheless did not lag behind the contemporary painting in other countries. But really, a new direction appeared here only around the middle of the XIV century. From the first century of the period under review (1250–1350), few wall painting monuments have been preserved.

Biblical images of the end of the 13th century in a small forest chapel in Kentheim, in the Swabian Black Forest, are distinguished by handicraft performance; their narrow, slightly curved figures still fully hold the Gothic tradition. 12 frescoes from the gallery of the cloister of the Rebdorf Monastery (near Eichstadt) in the Munich National Museum seem more subtle. The history of Daniel and the three Babylonian youths is depicted here on a blue background in red or brown contour drawing without shadows, with gothic-manner movements, but with living gestures. By the same time, the youthful slim figure of St. Christopher, performed on one of the pillars of the Abbey church in Maulbronn; Tode, in the first half of the fourteenth century, belonged to the remains of wall paintings in the castle in Lorchheim: the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi, etc. The first half of the fourteenth century includes the most ancient frescoes in the gallery of the cloister of Brixen Cathedral; in other churches of Tyrol, murals have been preserved that characterize the transitional period from the 13th century to the 14th century; The first half of the 14th century also contains the most ancient murals of Bohemia: scenes from the legend of Sts. George in one of the rooms of the castle in Neuhauz. The figures are marked only with contours on a gray background, transparent colors are superimposed without shadows, moreover, men and horses have more or less correct proportions, and female figures are distinguished by exaggerated Gothic curvature, faces are expressive, but gestures are not free. This style, apparently, is close to modern miniature painting.

Wall carpets everywhere compete with wall paintings. In the German Museum in Nuremberg and the Munich National Museum, you can get an idea of the development of this branch of art from the XIV century. Scenes from the life of the Minnesingers, from ancient history, as well as from the world of allegorical representations (storming the fortress of virtues of vices) are depicted on the famous embroidered colored wool along the canvas of the wall carpets of the Regensburg Town Hall. In the sacristy of Salzburg Cathedral there is a magnificent embroidered altar cover with New Testament images. Church of sv. Lawrence in Nuremberg has carpets made around 1375, decorated with the figures of the apostles.

Around the middle of the 14th century, in Prague, where artists and scholars from all over Europe flocked to the call of Emperor Charles IV, and in Nuremberg, where the urban class began to gradually recognize its lofty tasks, a new life began to emerge in painting; further south, in Tirol, a new movement directly adjoined the old painting. In Prague, the French, Italian, and Rhine elements were mixed; in Nuremberg, along with Prague's influence, Cologne also has an effect. Tyrol in church painting increasingly fell under Italian influence, while its secular art moved further the northern-Gothic tradition. Previously to other German schools, the Prague School, whose history was researched by Gruber, Voltman, Neuwirth, Julius von Schlosser and Max Dvorak, entered the new path. Already in 1348, the Brotherhood of Painters was founded here (a picturesque workshop), the statutes of which, published by Pangerl, were written in German. At the same time foreign masters worked here. Tommazo da Modena (Thomas of Mutina) stands out from the Italians; however, it is subject to great doubt whether he himself lived in Prague. Of the West German masters mentioned in 1359-1360. Nikolai Wurmzer from Strasbourg. From the documents we learn about the Prague artist Theodoric (Dietrich) who worked some time later (1367). That Italian artists worked in Prague is proved by a large mosaic picture completed in 1371 under the southern portal of the Prague Cathedral transept. Of the works of Tommaso da Modena, he signed only two paintings on the tree of the castle of Karlštejn; one of them is a simple sash altar with the image of the Madonna between St. Wenceslaus and Palmacius - entered the Vienna Imperial Gallery, while two boards of another folding remained in Karlštejn. Based on the style of these paintings, Crowe and Cavalcazelle attributed to the same master the wall painting that emerged around 1357 of the Catherine Chapel of Karlstejn, the main parts of which are the Crucifixion (before the altar) and the Madonna between Charles IV and his third wife (in the niche under the altar). Neivirt attributed Tommaso da Modena completed in 1456, an extensive cycle of paintings on scenes from the Apocalypse, adorned all four walls of the chapel of St.. Mary (part of this painting is preserved). The impossibility of this assumption was proved by Julius von Schlosser, and Dvořák showed that in general no Italian masters took part in the making of Karlštejn wall paintings, the mixed Northern Italian style of which is explained by the fact that northern artists made them in Italian miniatures or other patterns. The same can be said about those written between 1352 and 1370. biblical wall and ceiling paintings in the gallery of the cloister of the monastery of Emaus, quite closely resembling the drawings of the Bibles of the Poor. Similarly, no one recognizes Italian origin, for example, the easel painting depicting the Crucifixion with Mary and John in the same monastery. That Nikolai Wurmzer from Strasbourg could work in the chapel of St. Mary of Karlštejn Castle, does not contradict this view; but the views of Navyvirt, Shlosser and Dvorak differ on the paintings that could be attributed to him here or in neighboring Treppenhaus.

Fig. 281. Theodoric. Crucifixion of Christ. Picture on a tree from the chapel of the Holy Cross in Karlštejn

Undoubtedly, Prague's master Theodoric owns his main work, the Chapel of the Holy Cross in Karlstejn Castle, whose decoration with wall and easel painting was completed around 1365, most likely. The lower part of the walls of this room covered with two cross vaults is lined with Bohemian stone. Their upper part is covered in several rows of 125 paintings (originally 133), written on quadrangular wooden boards framed with gilded plaster ornaments. The arches of the window niches are decorated with frescoes. The main image in the niche of the western window represents God the Father, seated on a throne in a golden mandorla, and against Him is the Lamb with seven horns. The special character of the chapel, however, is due to the aforementioned pictures on the tree, depicting for the most part the half-figures of saints on a dull-gold background with patterns. The main picture is “Crucifixion of Christ”; beside Jesus - Mary and John (fig. 281); two side boards with the image of St. Ambrose and Blessed Augustine are in the artistic and historical court museum in Vienna. These paintings are extremely important in historical and artistic terms. The figures on them, strong and broad-shouldered, slightly constrained, have calm but distinct features of faces with large eyes, a wide nose, lowered corners of the lips, full cheeks, a wrinkled forehead. In general, they truly convey the spiritual movement and external traits of people and occupy a kind of intermediate position between the old idealism and the new realism. Despite the golden backgrounds, they no longer have a predilection for dark contours, but there is noticeable modeling with gray shadows and a brush. To the best works of the Prague school also belong very strong life-size figures in the paintings from the life of Charles IV, interspersed with apocalyptic scenes on the walls of the chapel of St. Mary's These pictures Dvorzhak attributed brush Nicholas Wurmzer. Of the easel paintings of this school, only two more should be mentioned: Madonna with supporters in front of her, Charles IV and his son Wenceslaus, in Rudolfinum, in Prague, and donated in 1385 by an Prague burgher to the Mülgauzenana-Nékare church altar with images of the Crucifixion, Annunciation and Ascension of the Virgin. Thus, the influence of the Prague school extended to Neckar.

Artistic development that took place in the XIV century. in Nuremberg, investigated by Tode. The murals of the town hall, which appeared, perhaps, even before 1350, were not preserved. Their content served as examples of ancient linguistic justice, “which should have encouraged the justice of the warriors and judges, as well as notaries and scribes”. The paintings on the tree of the XIV century, preserved in Nuremberg, are distinguished by their handicraft. Above the others stands the “Behold the Man” with kneeling Abbot Geertzlach in the monastery church in Heilsbronn: written on a gold-patterned background, thin, haggard figure with regular features and a meek, suffering expression on his face is somewhat bent forward. The contours are still quite thick, the nude body is modeled poorly, but the entire image is already full of inner spirituality. The real progress of painting began in Nuremberg only around 1400

But Nuremberg, in contrast to Bohemia and Austria, is relatively rich in stained glass. The most famous row of windows of the church of St.. Sebald The Fuhrer window [6], executed in 1325 with images from the lives of the saints, is also distinguished by archaic forms and lack of communication in particulars; The Tuherov window (1364–1365), with very bright and varied colors, represents the Passion of the Lord; On the window of the family name Schürstabe (1379) are events from the removal from the cross to the Descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles. Contradictory shapes and colors generally give a bright whole.

From the works of Tyrolean wall painting, murals of secular content attract the attention of the various rooms of Runkelstein Castle near Bozen and show us the German style in its most pure form. The frescoes of the eastern and northern buildings represent illustrations for German medieval poetry - for example, to Niethart's poem “Violet”, to the novel Virita von Grafenberg “Vigalois” [7] and “Tristan and Isolde”. True, the chambers of Tristan and Vigalois with their monochromatic, painted in green paint, but with plastic shapes modeled with white highlights, according to Janic, were rewritten later. Paintings that have been preserved in their original form, for example, scenes from Niethart's poem, represent vivid and clear contour drawings, painted without shadows. Pictures of the western building present plots taken from the actual

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)