Architecture

In the preceding epoch, as we have seen, England, with its insular isolation, according to its rational artistic character, originally developed the early Gothic forms borrowed from France. In the middle of the XIII century. She began to work on a more consistent design and striving for upward proportions of continental architecture, but at the same time she did not abandon the narrow and long plan of her churches, and her attachment to jewelry soon led her again on her own way to new goals.

The choir remains cut straight, and one huge window breaks through its wall, making up the original symmetry with the window of the western facade, at the opposite end of the church. Facade towers are even rarer than in France, ending with pyramidal spiers. What is independently created by this average English Gothic, which the English themselves call the decorated style, is almost entirely in the field of ornamentation. It is very characteristic, first of all, the fan-shaped ramification of the ribs of the vault, which in this era becomes the general rule even where bridges between the ribs join; it leads to the transformation of the star-shaped vault into a net; then, especially characteristic is the appearance of patterned stone bindings that were not present to this day, the holes that are bent to the right and left (“Passe”) earlier than on the continent take a shape resembling a fish bubble or a fluctuating candle flame.

The majestic church of Westminster Abbey in London, begun in 1245 and finished in substantial parts around 1300, became an exemplary building for the new style. Proximity to French Gothic, seen, for example, in doubling of the supporting arches (in England mostly single) through the carving of window covers, it comes to the fact that the semi-octagonal chorus, in contrast to the English custom, is provided with a roundabout and a crown of chapels. The 14th century belonged to the main parts of the York Minster, which, although considered to be an exemplary Gothic structure among English churches, is distinguished by the simplicity characteristic of the continental architectural style of the era. The service columns of the complex pillars rise, without interruption, right up to the arch, but then disappointment awaits us: the arch is made of wood. The English style never gives up its shipbuilding habits at all. The facade is dominated by vertical slabs, and while the windows of the facades of the transept are far from filling the walls between the pillars, this Gothic system is used on the western facade, completed only in 1402. The said predominance of vertical lines makes York Cathedral seem more Gothic and at the same time being less English than any other English gothic creation.

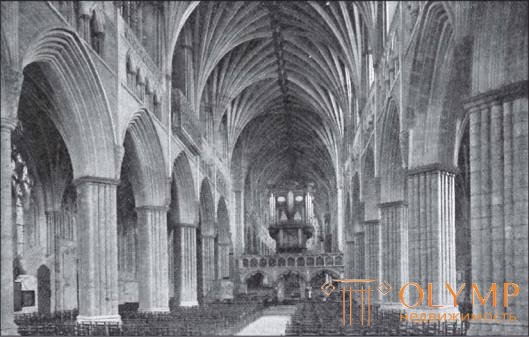

More English in their general character are, in any case, the Lichfield, Exeter and Herford cathedrals, belonging mainly to the fourteenth century. The Lichfield Cathedral has two facade towers with finished spiers and the same tower above the center of the cross. Only the lower windows — the side aisle windows — occupy the entire width of the walls. The prevalence of horizontal lines everywhere comes into its own again. Exeter Cathedral is distinguished inside by a rich dismemberment of pillars, dividing arches and ceiling arches (Fig. 262). The longitudinal rib, seated by numerous castle stones, passing through the highest points of all the arches of the middle nave, makes its covering similar to the box arch. In Herford Cathedral, the arches have such a negligible curvature that they hardly differ from high triangular gables.

Fig. 262. The interior of the cathedral in Exeter. From the photo of Fris

Unusually active was the XIV century. also in terms of the restoration and decoration of old large Norman and early Gothic cathedrals. In Or, the fall in 1322 of the Norman tower above the center of the cross of the cathedral gave rise to the construction of the famous central octagon with its magnificent through tower, the arches of which, however, with the inclusion of a lantern, were made again of wood. A new, unusually luxurious and picturesque chorus was built in Wels Cathedral, covered in various ledges and covered with various star-net and mesh vaulting systems, opening into the irregular octagon of the Chapel of Our Lady (Lady Chapel). In Gloucester Cathedral all the magnificence of the English decorative style is in particular the Cloister's Gallery (1381).

The main secular building of the XIV century - Westminster Hall in London, perhaps the largest hall in the world, covered without the help of columns or other supports. Its wooden ceiling is a real miracle of carpentry craftsmanship. But this room, completed only in 1398 and now serving as the forerunner of the new-gothic parliament building, already constitutes a transition to the late English Gothic. The main interest in the ruins of the royal castle in Elsem is also its large hall and in it an extremely skillfully arranged Gothic ceiling. The Chapter Room at the old Oxford Cathedral with its narrow windows is a typical example of early English Gothic, while Merton College has several rooms in the English style of the 14th century. But most of the dilapidated, ivy-twisted buildings that tell Oxford and Cambridge a unique medieval appearance belong to the late Gothic of the subsequent period.

Sculpture

In the reign of Henry III (1216–1272), also in England, the facades of large cathedrals were gradually covered with statues and reliefs, but since the English churches did not have such groups on portals as the French churches, the sculptural decoration of these cathedrals was simpler and, in any case less difficult. The remnants of this kind of sculpture, strongly affected by the raw island climate, give us a worse understanding of them than old copies, such as those found in Carter. In the second half of the XIII century, the English sculptural style under the influence of continental art reaches the highest grace and purity. In the 14th century, at first, a more vague, mannered direction was revealed, which is fully expressed in “Gothic bending”. Next to this, a national English reaction takes place, which initially, in the middle of the 14th century, thanks to its proximity to painting, which was under Italian influence, was somewhat indecisive, but at the end of this century it returns the sculpture to the numbness and rigidity of the old time. These style changes can be traced to the preserved sculptures of most English large cathedrals.

The magnificent sculptural decoration of the western facade of the Wels Cathedral was completed only in the XIV century. Madonna between the kneeling angels in the tympanum of the main portal already has a slight "Gothic bend"; she is clothed in clothes falling to the ground, typical for this era of female figures of continental sculpture. In the Lincoln Cathedral, 30 reliefs with images of angels in the axils of the arches under the windows of the choir still belong to the best style of the second half of the 13th century. Medieval English art in general did not create anything cleaner and more graceful than these reliefs, the general content of which is not entirely clear. A series of statues of kings on the facade of the same cathedral were executed in a tough, lifeless, decadent style reigning after 1377. The mutilated statues of saints on the western facade of the Lichfield Cathedral are sculptured in good XIII century style, but the statues of kings also show a tendency to schematization here. The soft national English style of the 14th century is characterized by sculptures in the vestibule of Exeter Cathedral: the heavenly coronation of the Virgin between 12 apostles in the upper row, the English kings in the bottom row, mostly sedentary figures, very expressive, with a purely British face. Strongly elongated figures on the capitals of the middle octagon of the cathedral in Ili, completed in 1342, are already full of mannerisms of the epoch of decline.

Changes in style can be traced in a similar way in the original gravestone sculptures, which are sometimes painted. At first, proud figures of knights with crossed legs together with quietly lying figures of church hierarchs are most often encountered, but during the XIV century they give way to motionless, frozen in mortal peace, figures with elongated legs. We are sufficiently convinced of this change in the type of gravestone figures in the sculpture of the Church of Westminster Abbey, the greatest mausoleum in England. In the clean, perfect style of the last quarter of the 13th century, the local monuments to Henry III (died 1272) and Queen Eleanor (died in 1290), wife of Edward I, were executed. These extremely expressive, cast bronze figures are in grandeur of design and thoroughness of execution. - the finest bronze statues of England. They are made by goldsmith William Torrell, who does not need to be considered Italian. By the nobility of their forms, they resemble the portrait sculptures of the Templar Krauchbak (died in 1296) and his wife (died in 1273). An even greater individuality of facial features, but at the same time a weaker technical performance, is the monument to the templar Emerument de Valence (died in 1323); he is depicted with his legs crossed, trampling a lion. The English direction of the 14th century is the direction in which soft, almost sluggish lines prevail. It finds expression, for example, in the graceful youthful alabaster figure of 19-year-old John of Eltham (d. 1334) and in the sculptures, also of alabaster, early deceased children of Edward III, resting next to a small sarcophagus. All the numbness of the forms, characteristic of English plastics at the end of the XIII century, is reflected in the schematically interpreted bronze figure of Edward III himself (died in 1377), lying on a sarcophagus of gray marble. In this decline plastics both ecclesiastical severity and artistic impotence are reflected.

Painting

English churches and castles were always decorated with frescoes. Unfortunately, performed between 1263 and 1277. Master William Old Testament, allegorical and historical (coronation of the king) frescoes in the room of Edward the Confessor in the Palace of Westminster and written between 1350 and 1358. frescoes in the chapel of st. Stephen in the same palace were destroyed by fire in 1834. On the basis of engravings and copies, Letgebi investigated in more detail the older ones, and Shnazy - the later frescoes of this “Westminster school”. Murals of the chapel of St. Stefan due to the abundance of sheet gold in them gave the impression of extreme variegation. Images of secular rulers did not have any signs of portrait resemblance either, but the biblical scenes were composed unusually vitally, and the oscillation between style and naturalism in the depiction of characters revealed some independence of artistic direction.

As a remarkable work of purely English easel painting at the end of the 13th century, Frey pointed to a poorly preserved, but excellently painted, painting in Westminster. In the second half of the 14th century, it seemed that Italian painters were often invited to England to perform easel paintings. Together with Wagen, we tend to attribute to the Italian brush the diptrich on the gold background, which is located near the Count of Pembroke in Wilton-Goose. One half of it shows the kneeling young King Richard II and the patron saints standing behind him, and the other half shows the Blessed Virgin facing him with blue clothes among the angels, also wearing blue clothes. A large portrait of Richard II in Westminster Abbey, “the most ancient of the modern images of English kings,” was probably also written by an Umbrian or Siena painter, as Shnaze believed. However, the stained glass windows and miniatures performed by the British in this era show that on the other side of the English Channel, French influence prevailed.

Among the oldest Gothic stained glass windows are harmoniously aged gray tones and here and there printed with more bright colors the windows of the Merton College in Oxford, dating back to the end of the XIII century. The luxurious color with abundant use of silver-yellow paint (Silbergelb) is distinguished by the image of the genealogy of Jesus Christ made several decades later and starting from the root of Jesse, in the eastern window of the Wels Cathedral divided into seven parts. The York Minster is heavily decorated with stained glass. Soft, with a predominance of gray tones, the painting of five “windows-sisters” (“Sister-windows”) dates back to the end of the XIII century. Around 1307, according to Whistlock, a window was made with images from the life of St.. Catherine of Alexandria. Painted in 1388, the western in eight divisions window ends with the “Coronation of Our Lady”. More mannered windows of the choir of 1380 In the York Minster, we have the opportunity to observe how English painting on glass with its predilection for gray tones, which only occasionally brighter paints occasionally joined, developed throughout the whole century.

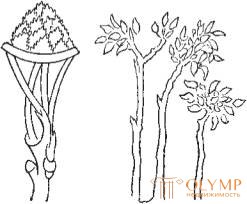

English painting of book miniatures is different, with the refinement of movements, delicate, fresh color and a particularly strong inclination to the image of symbolic scenes. In the transfer of natural, real life in the XIV century, it lags behind, however, the contemporary French and Burgundy-Dutch painting of miniatures. For the beginning of this epoch, the Psalter of the British Museum, written around 1250, is characteristic, in which rough drawings of biblical scenes, alternating between gold, red and blue backgrounds, are outlined with thick black outlines. In the Psalms of the same museum, the manuscript of 1310, under the golden or patterned background of the drawings, just below, a narrow strip of landscape already appears. According to the natural image of the sea in a miniature representing the story of the prophet Jonah, it is not difficult to guess that the artist was a resident of the island kingdom. The Psalter of Brother Robert Hormisby of Norwich, illustrated at about the same time, is known in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Her miniatures, filled with densely opaque colors on a gold background, were painted around 1250 in the Gothic French style. In one of the Psalters of the British Museum, which arose, however, only around 1350, slightly otchvechennye pen drawings take place up to the 67th sheet, from which begins a different style, more graceful and at the same time naturalistic. It is worthwhile to compare at least the trees of this Psalter (fig. 263) with the schematic, arabesque-like trees of two centuries of the earlier Bible (see fig. 182). This evolution is typical for the entire history of the image of trees in medieval painting. In the Bible of Huyart du Moulin, manuscripts of 1356, stored in the British Museum, gold backgrounds are again completely replaced by red-blue patterned ones, and beautiful individually transmitted heads of biblical faces are already modeled with paint. Thus, the spirit of time is manifested everywhere in the same direction.

Fig. 263. Trees. Book miniature: a - from the manuscript of 1150; b - from the manuscript of 1350 in the British Museum. From original copies

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)