Introduction Architecture

Emperor Frederick II, the brilliant Hohenstaufen, died just in 1250 in the far south, and just in 1400 the emperor Wenceslaus, son of the Bohemian king Charles IV, who had a great service to the development of spiritual life in the empire, was the foundation of the oldest German university, Prague, lost the German throne. It cannot be said that the years and a half centuries between these two dates were a time especially favorable for the German Empire. For all that, the turmoil and troubles of various kinds did not stop the development of artistic life in Germany. In the residences of the sovereign princes, as well as in the free cities of the Rhine and Schwab Unions and the North German Hanseatic League, artistic activity flourished, yielding fruits primarily in the field of architecture. French Gothic at this time and in Germany came out everywhere the winner from the fight against traditional forms. Therefore, it is clear that the leading role has now passed to the Rhineland countries, which most closely bordered France.

Fig. 264. Church plan of sv. Iveda in Bran. By Degio

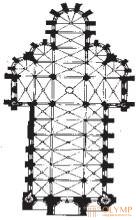

Fig. 265. Plan of the Church of the Virgin in Trier. By Degio

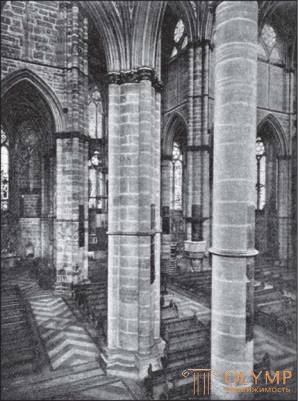

We have already seen (see Fig. 190) how the processing of individual French Gothic elements in Germany developed an independent, though not creative, transitional style and, as architects who studied in France, sometimes in the first half of the 13th century transplanted the entire Gothic system into separate cities of Germany, for example in Magdeburg. In the Rhineland masters who graduated around 1227, the arches of the round church of St.. Gereona in Cologne, the first came very close to the high Gothic. Window bindings, as Degio proved, are borrowed from Soissons. But the Church of Our Lady (Liebfrauenkirche) in Trier, apparently, was built later: at least until 1250 it was not over. Nevertheless, it remains the first Gothic church in the Rhineland and in general throughout Germany, and at the same time, as a Gothic central structure, it seems to be the greatest rarity. The prototype for it was the choir of the elegant early Gothic church of Sts. Iveda in Bran (fig. 264), between Reims and Paris. This choir in the church of Trier was repeated in the opposite direction on the western side of the transept (Fig. 265); all four branches of the main cross, forming a plan, have a polygonal end, so that both outside and inside a whimsically broken line, then protruding, now jutting inward, runs around the middle cross, above which stands a through tower. The four middle pillars are dissected by service columns (Fig. 266), eight round pillars of the circumference are slenderly raised, but both of them are also equipped with core rings. Simple window covers are copied from the windows of the longitudinal hull of the church of Saint-Lezier in Soissons. The exterior architecture still lacks support arches. And here from the French individual motives arose the German whole, the interior of which belongs to the noblest creatures of the Gothic style.

Fig. 266. The interior of the Church of the Virgin in Trier. By Degio

The next in time construction is the church of Sts. Elizabeth in Marburg, built from 1235 to 1283, but the western branches of its longitudinal body and its facade with two noble towers belong to the XIV century. The choir and transept of this church are early Gothic. The single-nave wings of the transept are exact repetitions of the single-nave choir, both of which have a polygonal end. The longitudinal hull is a three-nave hall church, but he received such a view later. The whole building has no prototype: it is a purely German creation, noble and alien to any pretentiousness.

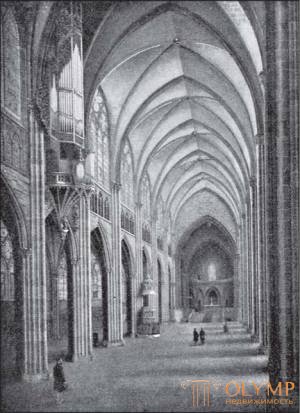

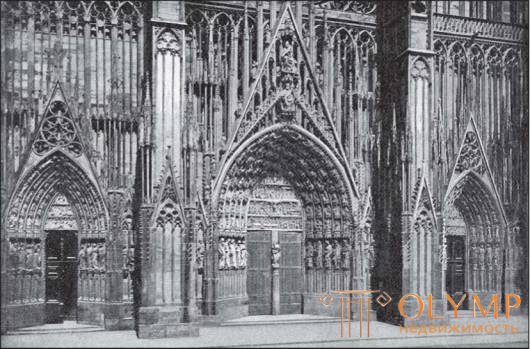

The construction of the praised Goethe and the Strasbourg Cathedral, the most beloved church in Germany, has been advancing with slow but sure steps. The preserved building reflects the complete evolution of styles, from the Romanesque to the late Gothic; but its individual parts are distinguished by high completeness, and the entire structure enchants us with a flight of fantasy, typical of medieval architecture. Around 1250, the western wall of the transept was finished - a masterpiece of the German transitional style. The Gothic, basilic-three-nave longitudinal body (Fig. 267), whose gallery of triforia brought to the windows, was built between 1250 and 1275. Some similarity in form with the New Church in Saint-Denis, detected by this longitudinal body, is forgotten in the face of the power and clarity of its grandiose, completely independent proportions. The western part of the building is associated with the name of the architect Erwin von Steinbach (died in 1318). The main work of Erwin before was considered the famous facade, divided into three parts in both vertical and horizontal direction. It is equipped with three portals and a luxurious "rose". Not connected with the walls, copiously trimmed slabs cover them like a forged grille. Openwork phials (turrets) and window and door gables envelop the facade like a lace veil. The middle part of the third floor, between the lower tiers of the towers, is obviously a later addition. We now know that three masters worked one after another on this facade. Degio believed that Erwin was the creator of the most beautiful and at the same time the lightest and most consistent of the three facade projects known to us, which the second time master had been working on. On the contrary, Moritz Eichborn tried to prove that Erwin was the last and the weakest of all three masters. But no matter how much they restrict his participation in the creation of this miracle of high Gothic, we still have the right to repeat the words of Goethe: “From the level to which Erwin rose, no one will push him away. Here is his creation! Come to him and recognize in him the expression of the deepest sense of truth and beauty of proportions, generated by a strong, courageous German soul. " The high tower with a spire, towering from the north side of the facade and inorganically connected with it, is in itself a very artistic work, but belongs to the 13th century.

Fig. 267. The interior of the Strasbourg Cathedral. From the photo

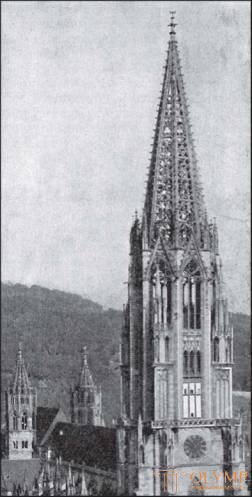

The same was the fate of the construction of the Freiburg Cathedral, but with the tower he was more fortunate. The interior begun around 1253 also of the basilica-three-nave, Gothic longitudinal body of this cathedral seems somewhat poor and dry, because it lacks the gallery of triforia. The choir is luxurious and noble, attached, however, only in 1359 by master Johann of Gmünd. The only tower above the noble porch of the western facade, with its beautiful octagonal lower part and the openwork, luxuriously decorated stone carving spire (Fig. 268), is the highest, clearest embodiment of the Gothic idea in the architecture of the towers. This tower had no equal to itself at an earlier time and remained unsurpassed in the following centuries.

Fig. 268. Tower of the Freiburg Cathedral. From the photo

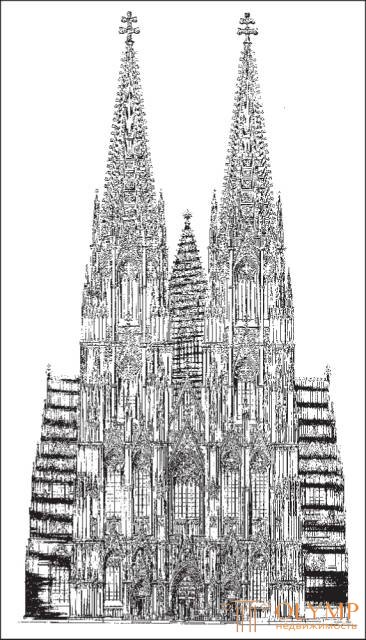

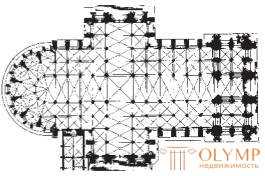

With the Strasbourg and Freiburg cathedrals, the monastic church in Wimfen, in Thale, can be compared in many respects, although its architecture is more French. Almost entirely French construction on German soil can be considered the world-famous Cologne Cathedral (Fig. 269). His huge choir, built between 1248 and 1322, is an exact copy of the choir of the Amiens Cathedral, and small but thoughtful deviations from the original confirm the assumption that Master Gergard, the builder of this choir, also built the Amiens Cathedral. The transept and the longitudinal case, in which the style of the Amiens Cathedral was reworked in a new spirit, was probably designed only around 1322 by Master Johann, who had completed the choir by this time. The transept is issued from the general plan more than in the Amiens Cathedral, and the five-nave longitudinal body is more vivid and clear than the longitudinal three-nave body of the Amiens Cathedral, is a preparation for the transition to the five-nailed choir (Fig. 270). The individual forms, which are thinner, sharper and more eager, resemble rather the details of the church of Saint-Ouen in Rouen. Until 1450, the construction of the transept and the longitudinal hull did not advance much, but a significant part of the western facade, probably even later, and the giant towers (see Fig. 269), for which the Freiburg Cathedral served as a model, was completed. The building remained unfinished until the XIX century, when with the help of the found old plans and the size of the finished parts of this grand building, with the participation of all the German people, it was brought to an end (1880). In its modern form, Cologne Cathedral is the largest and most sustained in style of all Gothic cathedrals. True, the purity of his style can be called a schematic, abstract sequence and gives the impression of greater dryness because the XIX century, which owns the execution of most of the entire building, perceived the style that became alien to him, of course, more rational than sense. The interior of the cathedral, with the height and sharpness of its forms, makes an almost eerie impression, and the outer buttresses and supporting arches are found here in such abundance that it seems as if they were invented for their artistic effect. Architectural criticism refers to the Cologne Cathedral severely, but for the open-minded friends of art, the greatness of the aspirant to the sky with all its parts, although in particular and strictly correct temple will always serve as a source of unique artistic pleasure.

Fig. 269. The western facade of the Cologne Cathedral. According to Schmitz

Fig. 270. Plan of the Cologne Cathedral. Around the house

Other luxurious Rhine-Gothic churches of the second half of the 13th century, such as, for example, the Cistercian church in Altenberg, directly adjoin other French models. But at the same time, in the churches of the mendicant orders, which served primarily for preachers, the Gothic system was simplified and schematized. In the churches of this kind, the transepts and the towers are constantly absent; despite the lancet arches, they often even have a flat surface and are lined with pillars; such, for example, are the Dominican Church in Constance and the church of the “preachers” in Basel, whose nave, even after restoration in 1356, retained a flat ceiling. On the contrary, the churches of mendicant orders on the Lower Rhine, such as the Dominican Church in Koblenz and the unpretentious Minorite Church in Cologne, are already vaulted.

As the direct descendants of the great creations of the Rhine Gothic called by us, only a few can be pointed out. In the choir of the monastery church of sv. Victor in Xanten, we see a repetition of the half of the Church of Our Lady of Trier. The influence of this latter is especially evident in the small churches on the Moselle. Church of sv. Elizabeth in Marburg served as a prototype for a number of Hessian churches. All of them, like this church, have a hall system and are equally equipped with a transept that does not correspond, strictly speaking, to the principles of a hall architecture. Among the churches of this kind, the cathedral in Alsfeld, the monastery churches in Wetter and Wetzlar and the city church in Friedberg - the church system of the hall system, characterized by chaste strength and graceful simplicity, the building whose enthusiastic description was made by its restorer Hubert Kratz deserve mentioning. As the side, in the words of Degio, shoots of this style should indicate the church of St.. Nicholas in Frankfurt am Main and the Church of Sts. Stephen in Mainz. The longitudinal building of the Strasbourg Cathedral was reproduced in the monastery church in Maursmünster. Imitation of the choir of the Cologne Cathedral is the choir of the church of St.. Vita in Munich-Gladbach. The influence of the style of this cathedral is noticeable in the charming church of St.. Catherine in Oppenheim, whose choir, however, again goes back through the Church of Our Lady of Trier to the Church of Sts. Iveda in Bran. But the most important building of the 14th-century Cologne school is the choir of Aachen Cathedral, with its gigantic stained-glass windows, giving it the appearance of light glass construction. By this time, the German Gothic style has long acquired considerable autonomy.

Of the secular high Gothic buildings in the Rhineland, majestic city walls, gates and fortress towers have been preserved. Between the public city buildings and here the main role was played by town halls and markets. Mainz Town Hall and the market are known to us, unfortunately, only by drawings. The walls of the market were jagged, with corner towers. Its lower floor, like almost all the rich houses of the time that went outside, had no windows. The three-nave main hall on the top floor had a ledge above the main gate, apparently serving as a chapel. Small similar protrusions like lanterns, the so-called horikami, usually decorated the front facades of town halls. From the 14th century town halls, there are still remains in Aachen and Cologne, but the Cologne town hall was built during the Renaissance, and Aachen - in the 19th century. The majority of civil buildings of the XII and XIII centuries were victims of the passion for the restructuring of old buildings that distinguished the XIX century; however, the Gothic house of the middle of the 13th century, the so-called Grashaus, remained in Aachen, which Essenwein considered the curia of Count Richard Cornielski (the German king during the interregnum of 1257–1272). This small, elegant building has in the hall of the upper floor, above three pointed windows with patterned bindings, seven niches closely attached to one another, in which statues of seven electors are erected. The halls of the Marburg castle (1288–1311) can serve as a model of palace buildings. The ten cross vaults of the two-room knightly hall are supported by four octagonal pillars; the openwork patterned bindings of the five front windows, of which the middle is placed in a ledge equipped with a pediment, are still simple and strict; the whole structure is noble grandeur.

Fig. 271. The Virgin and Child. Sculpture on the half-door column in the Freiburg Cathedral. From the photo

Plastics

In its most significant works, the Rhine monumental plastic until the end of the XIII century was more independent of architecture than the French; after being resettled to German soil from France, in most cases she was soon freed from the custody of her French mother. The sculptures of the western portal and the vestibule of the Freiburg Cathedral, performed by Moritz Eichborn between 1260 and 1275, were most important in the development of the Upper Rhine plastics. and composed probably by the Dominicans. Sculptures placed in tympanum, on archivolts and side walls of the portal, depict, in the spirit of Dominican philosophy, the events of the Old and New Testaments — all the teachings on the Fall and the Atonement, from the Creation of the World to the Last Judgment. At the portal between the portal gate is the statue of the Virgin and Child (fig. 271); 28 life-size figures are placed under canopies inside a vestibule near the north, south and west walls, under beautiful arched arcades. The extreme places, at the very entrance to the porch, are occupied by allegorical figures of the Church and the Synagogue, facing one another. In the sculptures of the porch they are opposed to each other, for example, the Savior and the “Prince of Peace”, five wise and five foolish virgins, seven sciences and seven Old Testament persons. In terms of style, these sculptures, depicting the struggle of the forces of darkness with the victorious light of the Church, are among the most independent creations of medieval German art. The predominant type of head, which also has the Mother of God, is a type characterized by a pear-shaped face, prominent cheekbones and supraorbital bones, a thin nose, a prominent chin and forcedly smiling lips, is highly peculiar. The body and draperies in places are modeled still rigidly and uncertainly. There is no doubt that these figures were carved from stone by different craftsmen, although their original models belonged to the same sculptor; but the deep feeling embedded in the main figures communicates integrity and artistry to the whole work. In contrast to the Mother of God in the vestibule, the image of the Mother of God, placed on the door jamb inside the cathedral (circa 1280), has softer features, a more lively smile and a “Gothic bend”.

Fig. 272. Three western portals of the Strasbourg Cathedral. From the photo

The famous western facade of the Strasbourg Cathedral (fig. 272) on the basis of the style of its sculptures should be considered as a continuation of the Freiburg porch and as an imitation of it. The sculptural images of the three western portals, belonging to the end of the 13th century, illustrate the content of scholastic philosophy and church dogma. И здесь на среднем столбе главного портала помещено изваяние Богоматери с Младенцем Христом на руках, господствующее над всем циклом изображений. По исследованию Мейера-Эльтона, лучше других сохранились большие статуи в нишах боковых стенок порталов и на прилегающих к ним частях фасадной стены. В среднем портале, у самых дверей, стоят статуи одной из сивилл и одного из ветхозаветных царей-пророков; остальные 12 ниш заполнены величавыми фигурами пророков. В северном боковом портале на тех же местах помещены изображения 12 добродетелей, попирающих своими стопами пороки. В южном портале изображены: слева — «Князь мира», как соблазнитель, с пятью неразумными девами, справа — Христос, как искупитель, с пятью мудрыми девами. В рельефах тимпанов, по большей части подновленных, представлена история Грехопадения и Искупления. Стилистическое развитие всех этих скульптур, прослеженное Морицом Эйхборном, начинается с южного портала, большинство статуй которого может быть произведено непосредственно от фрейбургских скульптур. Реймсское влияние наряду с фрейбургским заметно лишь в двух первых фигурах неразумных дев, которые вместе с некоторыми статуями добродетелей в северном портале — наиболее обработанные из всего этого ряда изваяний. Другие статуи добродетелей в северном портале уже вполне самостоятельны по стилю: их головы меньше, пальцы тоньше, драпировки свободнее и шире, но позы имеют готический изгиб, впрочем, заметный уже в некоторых статуях евангельских дев на южном портале. Совсем манерны, несмотря на меньшую изогнутость своих поз, фигуры пророков в главном портале. В их лицах заметно стремление к резкой, отчетливой моделировке подробностей, что, однако, не придает их экспрессии большей оживленности и индивидуальности. Мало-помалу и в немецкой пластике начинает сильнее сказываться зависимость от архитектурных форм, и в ней приспособление к отдельным элементам здания, как ни похвально оно само по себе, начинает стеснять свободу скульптурного стиля.

How superficial the Freiburg style becomes in the XIV century is shown by its echoes in the later sculptures of the Freiburg Cathedral itself, the western facade of the Basel Cathedral and the double portals of the church in Tanna, in Alsace. The animated features still retain the reliefs of the Freiburg northern portal, depicting the Creation of the World, but upon their close examination one can see that everything is already reduced to superficial agility.

In the Middle and Lower Rhine, the development of plastics is moving in the same direction, although in somewhat different ways. The first place should be placed here sculptures of the western and northern portals of the Church of Our Lady of Trier, executed after 1250. The architecture of the circular-arched western portal of this church is magnificent, with slender figures of saints crowned with buttresses on both sides; The images in the timpane above this portal, representing episodes from the Savior’s youth, are remarkably carefully executed. Although these images are poorly placed in a semicircle, the art of their performance, as opposed to the Freiburg plastic, seems more French than German; Clemen even called him "the purest art of Ильle-de-France." A bolder and more independent sculpture of the northern, smaller portal of the church named. Sculptures of the monastery church of Wimpfen in Tala seem to be handicraft replicas of French works. Fresh and independent images in the southern portal of the Mainz Cathedral and in the portals of the monastery church in Wetzlar (circa 1336). At least, Madonna on the western portal, despite her “gothic bend” and late Gothic smile, is a figure, still full of nobility and grace. Finally, sculptural works of the Cologne Cathedral are characteristic for the late period of their appearance. Marble relief over the main altar (1349), depicting the heavenly coronation of the Virgin and the twelve apostles, is sculptured sluggishly; on the other hand, slender angels playing musical instruments on canopies are delightful. The figures of the Savior, the Mother of God and the twelve apostles, placed on the pillars of the choir and performed between 1349 and 1361, are also charming. The mere fact that in some places the old coloring has been preserved on them is of great interest. However, their curved postures are too exquisite, and the humble expression of their faces is rather sugary; nevertheless, the careful, almost naturalistic fulfillment of details, along with the idealistic, typical interpretation of the faces, testifies to the successes achieved by art at that time.

Curious Rhine tomb plastic. German portrait art around 1250 was individual in terms of artistic originality; only after 1400 did it become individual in the sense of transmitting all the characteristic features of the depicted persons. This style change occurred gradually over a period of one and a half centuries. Something truly outstanding, having the lasting importance, appears at this time only as an exception. Around the middle of the 13th century, simple large Romanesque letters predominate in the inscriptions; from 1250, their place was taken by large Gothic letters, and from 1350, small ones. Until 1300, stone slabs decorated with portrait sculptures lie on the floor or on sarcophagi; Since then, due to the lack of space in the churches, such plates are often placed against the walls, in an upright position. We find the idealistic style of the Gothic era in some tombstones of the 13th century: in the Mainz Cathedral, for example, in the monument to Archbishop Siegfried III (died 1249), where the two crowned king were depicted next to the deceased, and in the monument to the Gragraph Thuringian Conrad ( d. in 1245), the master of the German order, located in the church of St. Elizabeth in Marburg. At the turn of the XIII and XIV centuries, the noble figure of the emperor Rudolph of Habsburg (died 1291) was painted, decorating his tombstone in the crypt of Speyer Cathedral. In this sculpture, the body is interpreted in an idealistic style, but the features of the face have already been softly executed and have a lot of life in them. During the XIV century, portrait gravestone sculptures spread everywhere, portrait resemblance becomes more and more accurate, details are processed more and more carefully. In the upper region of the Rhine, the works of the Strasbourg master Wölfelin von Rufach are interesting: Wilhelm in Strasbourg is the double tomb of the Earls Philip and Ulrich von Verdov (died in 1332 and 1342) and in the Lichtental monastery, near Baden, a noble monument to the Margravine of Irmengarde, the founder of this monastery (died in 1360). On the Middle Rhine, noteworthy: in the Mainz Cathedral - the tombstone to Archbishop Peter von Aspelt (died in 1320) with three images of kings, which he crowned; The monument to Archbishop Konrad von Weinsberg (died in 1396) is still Late Gothic in its general character, but it is brightly individual in its interpretation of the head (Fig. 273). On the Lower Rhine, whose Gothic gravestone has been studied in detail by Clemen in relation to style, the monument to Archbishop Engelbert III is remarkable in the Cologne Cathedral (died in 1368); the side walls of its sarcophagus are decorated with carefully crafted statues graceful in design; here the Burgundian-Dutch influence is possible, but the character of this work is completely German.

Of the works of wooden sculpture, carved choral benches are becoming increasingly important. Interesting benches from Altenberg (1287), in the Berlin Art and Industry Museum, benches of Xanten Cathedral (1300) are remarkable for luxurious arabesques of animal ornaments, and the benches of Cologne Cathedral (1300) are curious for their intermittent pathetic and playful sculptures. Mention should also be made of the benches of the choir of the church of Sts. Gereona in Cologne, the side walls of which are decorated with surprisingly slender, thin and stylish figures of St.. Hereon and Elena.

Fig. 273. Tombstone to Archbishop Conrad von Weinsberg in Mainz Cathedral. With photos of Krost

Since the XIV century. wooden carved altars appear on the Rhine, which played an important role in German art of the 15th century. and the first decades of the XVI century. Among the oldest surviving works of this kind is the main altar of the monastery church in Oberwesel (1331). True, the sacred persons of the Old and New Testaments, set in niches, adorn it, do not yet have an external connection with each other; small, richly painted and gilded figures, although still somewhat lifeless, but spectacular, and their posture is full of dignity.

German plastic cast bronze products are not particularly developed. Nevertheless, from the Middle Rhine works of this kind, the font of the Würzburg Cathedral, cast in 1279 by Eckard from Worms, the ornamental forms of which indicate the motifs of architecture to utensils, whereas the eight reliefs of this font on Plots from the earthly life of the Savior are distinguished by the purity of forms and freedom of movement, characteristic of the flowering pore of the Gothic style. The most remarkable of the Lower Rhine cast bronze work of the end of the XIV century. (It was hardly believed to belong to the 15th century) —a beautiful tombstone to Archbishop Konrad von Hochstaden in Cologne Cathedral. This magnificent recumbent figure is draped calmly and simply; her head with a free technique is striking in portrait likeness.

Thanks to the growing wealth of sovereigns, knights and citizens, the German goldsmiths gained a wider field than before for their use. The forms of Gothic architecture were transferred (when it seemed convenient - with the Gothic design, and in other cases without it) to the gold and silver dining room and church utensils. Ornamentation here also consisted of architectural forms proper, of more or less stylized new leafy or floral motifs, of human or animal figures, which were now often deliberately presented in a fantastic, humorous or satirical form. However, few of the reliquaries were performed in this new style. It is not known whether the Rhine or other origin is a 14th century reliquary in the church of Sts. John in Osnabrück, shaped like a gothic chapel. Undoubtedly, the Rhine work - plastically executed reliquary of St.. Simeon in the Aachen Cathedral, with the image of the Infant Jesus in the temple, standing on the table, on which there is also a vase of onyx; postures of figures - free and mobile, in the style of the XIV century. Of the reliquaries having the shape of a head, this includes the silver bust of St. Cornelia in the former abbey church in Corneli-Munster. This head, made in a highly naturalistic way, although somewhat harshly, clearly represents the transition to the style of the XV century.

Painting

During the first fiftieth anniversary, painting gradually became free from the restless, angular contour style in which it degenerated by the end of the Romanesque era, in order to move towards a more lively and at the same time more relaxed, though still symbolically stylish, Gothic style. In the first half of the 14th century, German painting, with all the grace and nobility of form, held on to generally flat contour techniques and only gradually came to a more picturesque distribution of light and shadow and to a better understanding of perspective. However, in some cases, the existence of Italian influence cannot be denied. France, Burgundy and the Netherlands in the development of the picturesque style went ahead of Germany, which, following them, still retained its artistic independence. The circle of depicted scenes expanded markedly. The names of individual masters and here gradually stand out from the general environment. With the exception of Italy, in no European country have so many works of late medieval painting been preserved as in Germany. The light on the Rhine art shed, research Ausm-Wert, Scheubler, Aldenhofen, Clemen and Firmenich-Richartz. In the Rhine region, as elsewhere, the Gothic architectural style greatly influenced the reduction of church wall painting, therefore the newly emerged decorative paintings, which meet the task of reviving architectural motifs, have come down to us in greater numbers than the ceiling and wall paintings. Remains of old church paintings were discovered in Basel, Freiburg, Lindau, Trier, Limburg, Boppard and Nideggen. But then all the local schools surpassed Cologne. In the XIV century, Cologne belongs to the focal points of world trade. With the beginning of the construction of his grandiose cathedral, the scope for painting opened, though more for easel than wall. Style angular-broken drapes with flowing folds, familiar to us from the church of St.. Gereon, repeated in the second half of the XIII century in the ceiling frescoes of the Church of the Virgin Mary in Liskirchen, Cologne, depicting old and New Testament events in bright colors against a blue background. Calmer lines, slimmer figures, more lively motifs of movements in frescoes written also against a blue background and belonging to the end of the XIII century, on scenes from the earthly life of the Savior and the lives of St. Cecilia in the altar of the church of St. Cecilia, in Cologne. A new, ideally typical language of the forms of the beginning of the XIV century is found in the solemn image of Christ in glory (Majestat) in the choir niche of the Breuweiler Church; in the same style was made a long series of wall and ceiling frescoes of the church in Ramersdorf, in Siebengebirge, preserved for us only in watercolor copies of the Berlin Prints office. Here was presented the full cycle of Christian images. Joy and sorrow were already reflected both in the gestures of the depicted figures and in the expression of their faces. But the most remarkable painting of the first half of the 14th century in Nizhny Reyns, preserved only because it was hung with carpets, adorns the inner walls of the choir fences in the Cologne Cathedral. This painting had to compete with the architectonic dismemberment and the colorful magnificence of the windows of the choir. And indeed, both the scenes and the individual figures are placed in gold-painted bunk gothic arcades on a colored carpet background. This painting is made of strong paints a tempera on chalky ground. On the north side are scenes from the lives of the Apostles Peter and Paul and St. Sylvester. On the south side are the lives of the Blessed Virgin and the Three Magi distinguished by the best forms and colors. Slender, flexible figures are drawn even without a full consciousness of the structure of the body, mental state is transmitted mainly by means of gestures, nevertheless, there is a clear distinction in the faces between the types of young and old men, good and evil, wise and foolish; light and shadows are almost as carefully distributed not only on draperies, but also on faces through white highlights.

The last quarter of the XIV century belongs to the image of the Crucifix over the tomb of Archbishop Kuno in the church of Sts. Castor in Koblenz. The gothic bend is barely noticeable here; the endeavor to convey the spiritual movements lurks in the figures of the Virgin and John. By the very end of the 14th century, there is a large Crucifix against a red background in the sacristy of the Church of Sts. Severin in Cologne. Here all the success achieved by the Cologne easel painting in the school of the master Wilhelm (see below) is already visible.

Secular wall painting suffered from gothic architecture, of course, less than the church. In the castles and civil buildings, she had at her disposal numerous wall surfaces. But very little has been preserved from all this, and more on the Upper Rhine than on the Lower. The most remarkable is the drinking room in the “battlement house” in Dyengofen, the murals of which are published by Durrer and Wegeli. The paintings illustrating Neidgart's “Funny Tale of Violet” resemble frescoes on scenes from “Ivaine” in Schmalkalden in the Hesse Palace.

But the Upper and Lower Rhine were not inferior to each other in terms of church painting on glass. A change in the language of forms occurs more slowly in it than in fresco or easel painting, and until the end of the 14th century it remains faithful to curved Gothic figures. Throughout this era, silver yellow has been little used in Germany; in the XIV century, more shading is used in both parallel and mesh lines, and the shading parts do not change their original color. On the Upper Rhine, Alsace is famous for its stained glass windows (they are beautifully published by Robert Brooke). In the Strasbourg Cathedral, you can trace the complete evolution of their style. The first Gothic window in the full sense is considered to be the closest window to the choir in the north wing of the transept. It was probably made around 1260. His images are presented below St. John the Baptist, at the top - sitting on the throne of the Queen of Heaven with Baby. The purple mantle on the blue lining forms a magnificent combination of tones with the yellow delicate attire of the Mother of God. In the east-west direction, the windows of the north wall of the longitudinal building in the first half of the 14th century were gradually decorated with figures of bishops and kings, whose poses became more and more minuscule, and windows of the southern wall became figures of holy wives in the same style. In the middle of the XIII century belong six windows of the chapel of St. Catherine, made by master Johann from Kirchheim. The characteristic gray-bearded figures of the apostles are full of harsh importance, but their draperies already show the soft, flowing style of the time. These typical images are imbued with stately dignity. The mannered style of the second half of the 14th century is manifested in the depiction of the struggle of virtues with the vices on the western window of the north wall of the longitudinal body. The windows of the tower were decorated with biblical and symbolic compositions, placed in medallions only around 1400; one can see in them the success achieved by that time of a more natural transfer of the nude body.

A number of windows in the church of Sts. Florence in Nieder Gaslach, in Alsace. Nine narrow choir windows, of which the average was performed around 1260, and the rest in the next decades to come, are decorated with figures of saints and kneeling supporters standing at their feet. A century later, high windows of the aisles were made with images from Sacred history and the lives of the saints. Skillfully arranged and alive in color, these images, also in drawing, reveal the successes of their time. This last improvement, however, cannot be considered the progress of the painting style on glass, which

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)