In the ruins of Pasargad, the name Cyrus is found only in the inscriptions, in the ruins of Persepolis, it already completely disappears, but the more often there are inscriptions of the names of Darius I and Xerxes I, which only occasionally are joined by the names of later kings. Therefore, there can be no doubt that the ruins of Persepolis contain monuments of the further development of Persian art under Darius. As a matter of fact, of the ruins in the vicinity of ancient Persepolis, only the palace terrace in the residence (Chil Minar, or Takht-i-Jemshid) and the tombs in Nakshi Rustem are interesting for us.

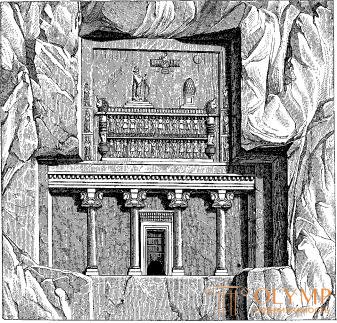

Fig. 236. The royal tomb in the rock near Nakshi Rustem. By delafua

In addition to the tombstone mentioned above, we find in Nakshi Rustem only facade tombs in the rocks. To four such tombs of this locality (fig. 236) one should add three more in the rocks behind the large terrace in Persepolis. The oldest of them is the tomb of Darius in Nakshi Rustem, recognized as such by the length of the inscription on it. Most of this monument is an imitation of the facade of a house or a palace. Above him, in a special field, placed the image of a two-story artistically executed throne stage, on which stands the king, praying to the deity of light. The facade represents a portico on four columns, bounded laterally by walls. The door leading into the tomb occupies the entire space between the two middle pillars. Above the door trim, which looks like a triple frame, is an Egyptian grooved cornice decorated with a triple row of leaves, which plays the role of decorating doors, windows and niches in all Persian buildings. The columns consist of a base in the form of a shaft, lying on two quadrangular plates, from a smooth round rod and from the famous Persian capital with the heads of bulls in its simplest form. On the two sculptures of the front of the bulls, facing their backs to one another, and on the saddle-shaped notch between their necks rests a short, projecting transverse beam, topped with a slab. On it and on the necks of bulls, the upper parts of the facade rest: an architrave consisting of three smooth strips, a cornice with a row of teeth and a frieze stretching above it with images of lions walking. The throne stage of the upper field, regardless of its architectural supports, is supported by two rows of 28 human figures one above the other in different clothes with their hands up. From the inscription it is clear that these figures are the personification of 28 regions of the Persian monarchy. On the stage stands the king in clothes, forming many folds, with a tiara on his head, turning to the right and raising his right hand in prayer; before him is the altar upon which the sacred fire burns; the disk of the sun is floating in the sky - the source of all light and fire; an image of Agura-Mazda (Ormuzd), the ancient Persian god of light, is placed higher in the center of the sacred winged ring in the form of a bearded half-figure in royal attire. This image represents everything that has come down to us from the religious art of the Persians. The construction of the tomb's façade described only very remotely resembles the Egyptian prototypes, which we find in the Beni Hassan mountain tombs and in Asia Minor tombs in the rocks of Paflagoniya; in particular, the use of alien elements is clearly noticeable. Even the Persian capitals with bull heads point to analogies in the Egyptian and Assyrian arts; but these analogies are by no means so striking as to take away from the Persian column with bull heads its artistic independence. The architrave, despite the absence of a crowning cornice, is obviously inspired by an Ionic or more ancient pattern; On the throne stage we find such ornamental forms as a series of so-called ovos, consisting of alternatingly wide and pointed leaves, and the so-called pearl string, consisting of spherical elements, alternately round and elongated, forms that Greek art invented, although the tendency to them is observed in more ancient works of art. This includes the Egyptian grooved door cornice, the Assyrian image of the deity over the figure of the king, the Assyrian general character of the whole sculpture, which, of course, shows the transfer of folds in the spirit of the archaic art of Greece, and Assyrian style, and Pasargad style Cyrus image. Already from this, it is clear that Persian court art was the first to follow an eclectic direction, and that its further development in this direction was probably dependent on the accession of Egypt to Persia, which followed in the meantime; but if, in addition to Darius’s tomb, we turn our attention to six other royal tombs in the rocks, then the sharp boundaries of this development will be immediately determined: these six tombs belong to a later era, and although the newest of them is 150 years younger than Darius’s tomb, similar to this last and to each other like two drops of water. Most of them do not have only a frieze of lions on the architrave.

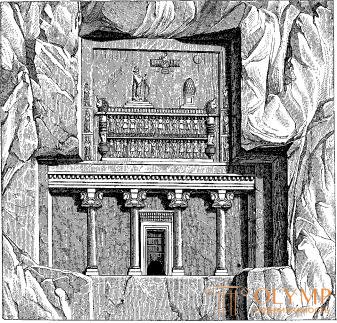

Fig. 237. Complicated Persian column from Persepoli propylene. According to Flandin and Costa

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play gameGame: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

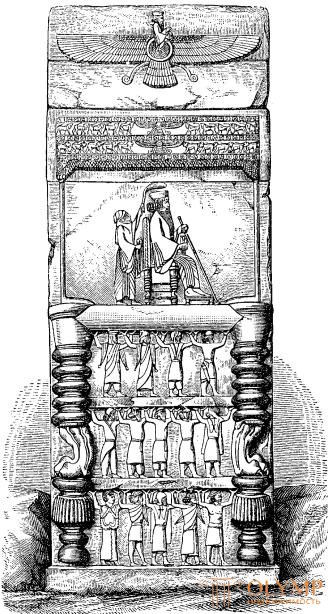

Play gamePersepolsky Palace Darius for the ceremonial receptions is known as the hall with 100 columns. Its ruins contain enough data in order to be able to mentally restore it. Being intended for solemn occasions, it did not contain any residential, side premises. It was a huge, quadrangular hall 75 meters long and wide, with a ceiling supported by 100 columns 111/2 meters high each. On the north side there was an open portico, into which two doors led from the hall; it was about 56 meters long and 16 meters deep. The ceiling between the side walls was supported by two rows of columns, eight in each. The outer edges of its side walls were decorated with sculptures of winged bulls with a human head, in the nature of such Assyrian figures. The columns all belonged to the category of the luxurious Persian columns described above. The walls of the main hall were divided into parts by doors, niches and windows. On the door frames we found images of the king sitting in his tent on the stage, under the protection of Agura-Mazda hovering above him and receiving honors accorded to him (fig. 238).

Fig. 238. King on the throne. Persepolian relief. According to Flandin and Costa

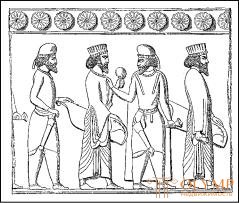

In relation to the style next to these Persepolian reliefs from the time of Darius should take place a relief image of this sovereign, carved on a rock along the road from Ecbatana to Babylon. It is located at a height of 50 meters above the road and strikes from afar with its long inscription, in which Darius announces his deeds. He rests on his bow and tramples the foot of a captive writhing beneath. Behind the king are two bodyguards. New captives are being brought to him in bonds. Above it hovers Agura-Mazda in its winged ring.

In all these Persian reliefs from the time of Darius, Assyrian style and composition techniques are noticeable; Persian immaturity is found in the constant repetition of the same, once and for all accepted, motives and in the stillness of the depicted figures, which in themselves would be capable of movement; The spirit of Greek freedom is felt in a better understanding of the conditions of the relief, in an abundance of folds, although outlined in the old way, schematically, and in greater purity and softness of the muscles, and, however, the hair on the heads still stand out, as before, monotonous and rough.

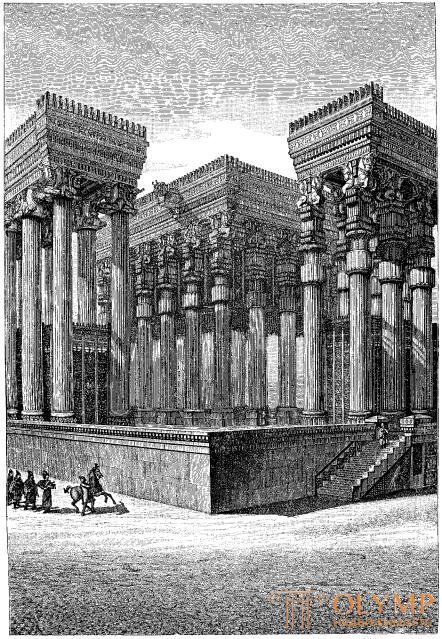

Fig. 239. Hall of Xerxes in Persepolis. On the restoration of Shipie

Xerxes built for himself on the southern side of the main terrace of Persepolis a residential palace facing the cool north , much larger than Darius’s palace. According to the plan, the central hall of this building had 36 columns (instead of 16), and in the portico - 12 (instead of 8). Some change in artistic taste is noticeable in the sculptural works that adorned this palace. True, the king and in him is under an umbrella, which is kept over his head by a servant following him, but the king is no longer fighting the monsters, and instead of them appears an image of beautiful bezborodyh young servants, carrying carpets, vessels, baskets; without a doubt, it is a sign of a softening of manners; the relief style also becomes softer: its forms are made more rounded, light and smooth.

Fig. 240. The capital with the unicorns from the hall of Xerxes in Persepolis. By Perrot and Shipie

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play game

Fig. 241. Dannies carrying gifts. Persepolian relief. According to Flandin and Costa

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play game

Fig. 242. Cypresses and palm trees. Persepolian relief. By Perrot and Shipie

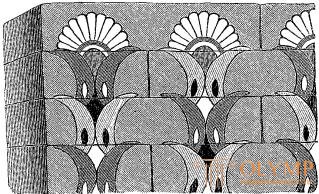

The sculptural decorations of the wide staircases were abundant and magnificent not least of all the buildings. And here in each of the four triangular wall spaces of the stairs were depicted lions, tormenting the bulls, and on the front middle wall - the royal bodyguards. On the parapets of the stairs there were warriors rising from step to step. The wider front wall of the first pair of stairs, which followed the second, was divided by vertical stripes into three fields occupied by images of people and animals, long lines leading to the middle: on the left — courtiers, soldiers and servants of the king, his chariots and horses; on the right are the ambassadors of the provinces with their gifts, fruits, and beasts. An attempt to diversify the presented is found in the fact that the walking figures in some places turn back (Fig. 241); the desire for diversity can also be seen in the image of animals - camels, zebu, horses, sheep, driven by people; the need for greater wealth of forms is manifested in the drawing of trees, which interrupt the rows of animals and people; only cypresses and palm trees are depicted in the trees; при грубости общего очертания кипарисов их ветви и плоды в какой-то степени естественны, но пальмы имеют вид прямо скопированных с египетского "дерева пальметт": цветочные чашечки с завитками, причем из верхней распускается пальметта, как бы умышленно-условно обозначают собой ствол пальмы, а та фигура, которая, собственно, только называется пальметтой, играет здесь роль пальмовой верхушки (рис. 242). Ландшафтных фонов, какие нередко встречаются в египетском и ассирийском искусстве, в персидском придворном искусстве не имеется.

The facilities of Xerxes on the Persepolian terrace are completed with kerfs, with their narrow side facing the main staircase of the terrace, and the long one - to the staircase leading to the palace of the king. Thus, containing passageways in both directions, the cuts served to enter both the terrace and the buildings of Xerxes; they consisted of an architrave resting on four massive pillars and four columns; the aisles were in the long side between these pairs of columns, and in the narrow - between the wall pillars, on the sides of which stood a winged bull with a human head of the Assyrian type already known to us.

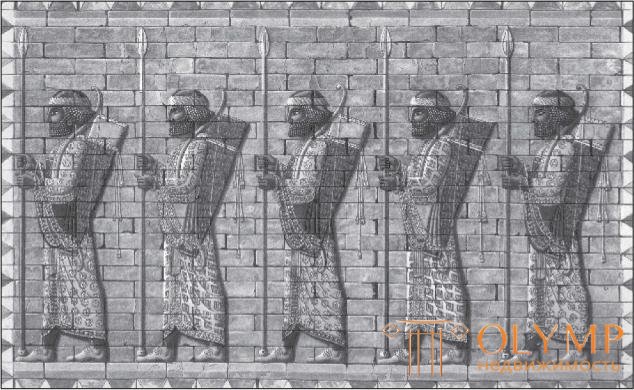

Fig. 243. Capital of the column from Susa. From the photo

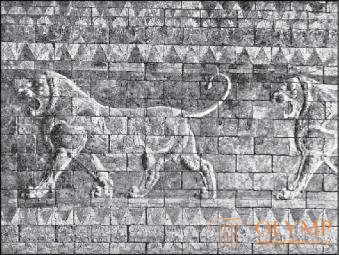

Other buildings on the Persepolian terrace, of which the Artaxerxes-Okha inscription (362-339 BC) is located at the latest, is less significant and less instructive for us. Persian palaces in Ecbatana and Sousa cannot boast with essentially new forms either. The stone columns, opened during the excavations of Delafoua, started by Darius and the ceremonial palace in Susa, completed by Artaxerxes Mnemon, whose remains can be admired in the Louvre Museum in Paris (fig. 243), represent an excess of forms common to other monuments of fully developed Persian art. We find something new here in friezes made of colored glazed clay slabs. The surviving pieces of these friezes are folded and replenished with great skill; they are also in the Louvre. Suza lay on the edge of the Mesopotamian Plain. The fact that here, as in Babylon, the brick served as material for the performance of some tasks of stone plastics, should be considered not so much evidence of the further development of Persian art under Artaxerxes Mnemon, as a phenomenon depending on geographical conditions. The most famous are the frieze depicting the royal archers (fig. 244) and the frieze with lions, stored in the Louvre (fig. 245). Where, in fact, these friezes were located, it is not quite clear; However, the frieze with lions, distinguished by subtlety in the decoration even lived on their heads, at least decorated the high part of the building. As for the frieze with archers, it should be noted that none of them had a head preserved, and all heads were reproduced again on the scale of the heads on the stone reliefs of Persepolis. The uniformity of the figures in both friezes is striking; it will become clear to us if we recall that these reliefs were made by means of a clay impression in the same form. Nine figures of archers, folded from the fragments of a frieze, are resting with both hands on spears; the bows are thrown over their shoulders, and each one has a quiver behind it. In the clothes, together with the image of folds already known to us, we see patterns consisting alternately of rosettes and rhombuses. Paints are limited to white, black, brown and yellow, except for the bluish-green, prevailing in the background. Red paint does not occur. In the rims around these paintings, as well as on other fragments of similar tiled works of art of Susa, we find all the ornaments of Persia, as if a list of all its motifs: jagged teeth, partly with pointed holes inside, stripes of triangles, ribbons with rosettes, Assyrian rows palmettes, interconnected by continuous arcuate ribbons, and nearby are various variations of the palmette and palm tree motifs (Fig. 246). And in this area the Persian court art has not created anything new.

Fig. 244. Frieze with figures of archers in Susa. On watercolor by Max Kunert (photo) and on the restoration of Dresden Albertinum

Fig. 245. Frieze with figures of lions from Susa. From the photo

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play gameGame: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play game

Fig. 246. Suz palms and palms. By delafua

The evaluation of Persian architecture is not so unfavorable. Recognizing where she borrowed most of her individual motives is not difficult; but in all its community, the architecture of the Persian palaces seems to be largely truly local, a peculiarly beautiful product. Spacious terraces that serve as the foundation of buildings, comfortable double staircases, scaffolding of columns consisting of several parts and richly ornamented, colored architraves and ceiling beams merged into one beautiful whole. Not only between the parts of the columns, but also in the decoration of doors and windows there was a strict proportionality, based, as Delafua proved, on certain numerical relations (width refers to height as 1: 2, 2: 3, 2: 5), which are observed for the first time here. and in Greece. Of course, the Persian architecture of the Achaemenid times was not destined to exert a productive influence on European art, which would quickly acquire international significance, but for the Far East, Persepolis’s wonderful buildings were, so to speak, the lights of the cleaner art world. We will see further that the beginnings of India’s Buddhist art are imbued with Persianism.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)