Syria, lying between Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean Sea, between Egypt and Asia Minor, from the very beginning of its history, both artistically and politically, alternately fell into dependence on one or another powerful neighbor, which we are known as the eldest of civilized nations. all over the world. Turning her eyes across the sea, Syria ended up at least in the 1st millennium BC. e., as a distributor of the heritage of the Egyptian and Babylonian-Assyrian cultures, as she understood them, with the help of her ships to the farthest west of North Africa and Southern Europe, and even further. The inhabitants of the Assyrian coastline, to whose share this role fell, were the Phoenicians, these "royal merchants" of the pre-Hellenic period of the ancient world. Cyprus, an island of copper and cypress trees, the only large island near the Syrian coast, was occupied by the most ancient of the Phoenician colonies.

Cypriot art, whose earlier connection with the Mycenaean, we have already pointed out, appears in the first half of the 1st millennium BC. e. only a branch of the Phoenician. Turning to the continent, the same can be said about Palestine, which borders Phenicia in the south of the Syrian region. The Jews were all the more forced to cling to the art of their closest relatives and neighbors, because with the development of their concept of a single, personal, but invisible deity, they set themselves a task that the independent processing of Egyptian and Babylonian artistic elements could not go along with.

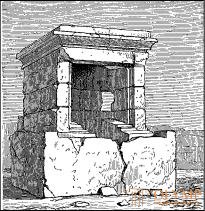

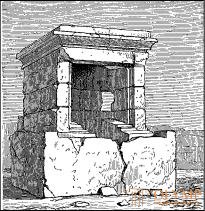

Fig. 211. The ruins of the temple in Amrif. According to renan

It was believed that the most ancient of the surviving works of Phoenician art, with the exception of some walls, made of hewn prismatic stones, and structures in the rocks, devoid of any decorations, do not go any further than the 1st millennium BC. er but some researchers (Gelbig) imagined that they had managed to discover the Phoenician art of the 2nd millennium BC. e., and, moreover, in monuments that are not inferior in value to the Mycenaean. We have said above that we can not join this opinion. Evans pointed to the possibility of quite the opposite, namely that the famous alphabet of the Phoenicians, who until now had been looked upon as the inventors of the letter, was borrowed from the Mykene.

The ancient Phoenician cities of Arad, Maraf (Amrif), Gebal (Bibl), Sidon, and Tire stretched along the narrow coastal strip from the north to the south, between Lebanon and the blue Mediterranean Sea, often coming out of this range to the coastal islands. Until the end of the 2nd millennium, in trade and other relations, Sidon took priority, shortly after 1000 BC. e. ceded its dominance to Arada in the north and Tira in the south. Worthy of attention monuments of ancient Finnish architecture preserved almost exclusively in Amrif, a city related to Arada. Of these, we must first mention the remains of several temples. But only one of them survived to this day (Fig. 211). In the middle of the courtyard, 48 meters long and 55 meters wide, whose walls are carved into a rocky hill, at the foot of 3 meters high, covering an area of 51/2 square meters and integral with the mass of the courtyard rock, a small temple in the form of a chapel with a flat roof, three deaf walls and one, front, open. The roof is vaulted on the inside, encircled on the outside by an Egyptian cornice and consists of one slab. Renan found another chapel not far from this one completely collapsed; nevertheless, it was possible to verify that the concave strip of its eaves was ornamented with Egyptian ureyas.

The image on a biblical coin of a later epoch (Fig. 212) proves that the Phoenician temple, usually located in the spacious courtyard that made up its main part, sometimes contained only the sacred symbol of a deity — a natural clump of a meteor or an artificial cone-shaped stone. On the right of the coin is the sacred courtyard of the temple with a cone-shaped stone towering on it, on the left - the chapel adjacent to the courtyard of a Greek style.

Fig. 212. Biblian coin. By Perrot and Shipie

Monuments of the ancient necropolis in Amrif also give us several points of departure. One of the gravestones (fig. 213) consists of a low square base and three cylindrical tiers, which approach the top of the tower, diminishing in size. At the corners of the basement of the round wall protrude the front half of the body lions. Both upper tiers are surrounded by a raised, toothed cornice with a crown of Assyrian step teeth. Here we see the imitation of Assyrian models, as well as in the temple described above, the imitation of some Egyptian forms.

Fig. 213. Gravestone tower in Amrif. According to renan

Cyprus, from ancient times, the sacred island of Phoenician Astarte, Greek Aphrodite, which came out of the foam of the sea off its shores, abounded in the temples of this goddess. On its southern coast from west to east were the following cities: Paphos, Kourion, Amaph, Kition (Larnika). Then, inside the island, were Idalia (Dali) and Golgos (Afyeno). On later coins with the image of the main Paphos sanctuary of Aphrodite and the pigeons attached to it (Fig. 214) this sanctuary has a distant resemblance to architecture with small models of temples in Mycenae, embossed from gold leaf, we also see sitting pigeons on them (Fig. 215 ). This is explained in different ways. Some of the writers see in the middle, higher part of the building only an extension for the entrance gates of the temple courtyard, while others see in the image an indication that the temple was divided into three spaces, of which the average was higher than the side, like the Egyptian hypostyle hall or maybe the Mycenaean male megaron.

More tactile results of the excavations in Cyprus were obtained in terms of Phoenician architecture ornaments . Capitals of columns, carved from the same piece, like their rods, are found in Cyprus much more often than on the continent. Both here and there, there is no shortage of ornamented stelae, plates and other objects that introduce us to the Phoenician ornamentation. Of course, one must be careful not to attribute to the Phoenicians the remnants of the later Greco-Roman art, which can be found a lot in Cyprus and in Syria. But it is very interesting that the oriental motifs of the ornament were so much included in the flesh and blood of the artists of these localities that, until later times, they brought them into Greco-Roman forms.

Fig. 214. Paphos coin. By Perrot and Shipie

Fig. 215. The image of a temple, embossed from a gold leaf, found in Mycenae. According to Schuhardt

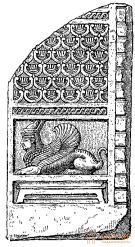

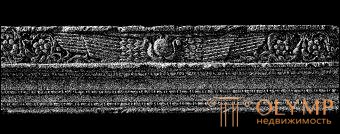

On the continent, in Gebal, Renan found a Egyptian capital of a character consisting of a round rod and a jib, and not far from the designated place, in the Edda, a small capital consisting of a ring, a pillow and a quadrangular slab, resembling Mycenaean and later Doric capitals. In Cyprus, richer and more varied forms have been found: of these, we first point out a few capitals in the Louvre Museum, in Paris (Fig. 216), which probably originated from Egyptian capitals in the form of a bell flower and palmettic trees, which represent the embryonic form of the ionic capitals. Apparently, these capitals did not belong to buildings, but to grave stelae and did not support anything. In fig. 217 very characteristic capital. Above the cup with volutes facing in different directions, between which a triangle is inserted, decorated with an image of a crescent and a solar disk, there are two or three cups with volutes twisted upwards, and in the middle of the top cup there is a ray-shaped Syrian lotus bush, which we have already seen in Egypt. This transformation and independent application of the motif of the "Egyptian palmettic tree", as Richl pointed out, is the only original artistic creation of the Phoenicians. We see the same motif in abbreviated form in the proper "Phoenician palmette", countless times repeating in Phoenician art. On the two alabaster plates in the Louvre (fig. 218 and 219) found in Arad, we see, as it were, a carpet pattern made up of rows of these palmettes. The Assyrian ribbon weave borders this pattern. On one of the slabs, in its lower part, a winged sphinx is depicted, and on the other - a new palmette tree made up of Phoenician palmettes, similar to an Assyrian sacred tree, placed between two vultures that climb it. The Egyptian winged disc repeats countless times in Phoenician ornaments, often in conjunction with the serpent-urei; the Old Haldean crescent with a round star or solar disk is also often encountered. How these symbols were subsequently mixed in Phenicia with the Greco-Roman ornamentation, shows us a piece of frieze from the temple in Gobal-Byblos, stored in the Louvre Museum (Fig. 220).

Fig. 216. Cypriot capital. From the photo

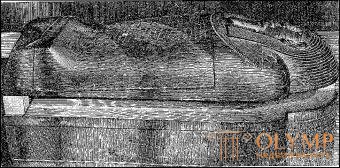

The same combination of Egyptian and Assyrian motifs, as in architecture and ornamentation, we see also in the plastic of Phenicia and Cyprus. How long the Egyptian influence retained the leading role on the Syrian continent, proves the Ehmunazar sarcophagus, found in Sidon and stored in the Louvre Museum (Fig. 221). The stone cover of it, according to the Egyptian custom, is a semblance of the deceased mummy with an obvious portrait of the head. It is quite possible that this statue is executed by the hands of the Egyptian. However, it refers only to the beginning of IV. BC e.

Fig. 217. Cyprus capital. By Perrot and Shipie

The development of Phoenician small plastic on the continent of Goethe sets out on the basis of terracotta figures found in Phenicia. From the period of the first rule of Egypt over Phenicia nothing is preserved. In any case, in the most ancient terracotta figurines the intention to imitate Assyrian art is noticeable. This is clearly seen, for example, in a small chariot drawn by fours in the Louvre Museum. It was only after the Phoenicians again fell under his dominion during the Sais era of Egypt that their artists began to imitate the softer Egyptian style. This is manifested mainly in the terracotta figurines of seated women with Egyptian headgear and statues of the dwarf god Bes (see Fig. 141). But from the VI century BC. e. The Phoenicians began to imitate the archaic style of the Greeks. This can be seen in particular in full-length female figures, in their Ionic costumes and hairstyles. Of course, in view of the low independence of the Phoenicians in terms of art, these works cannot be considered prototypes of the archaic Greek style, for which they took them for a rather long time. Phoenicians have always been and remained imitators.

Fig. 218. Phoenician alabaster plate. By Perrot and Shipie

Fig. 219. Phoenician alabaster plate. By Perrot and Shipie

A similar course of development is represented by Cypriot statues, carved from local soft limestone, copies of which are in all archaeological museums in Europe. But most of them fell into the Louvre and, thanks to Chesnol, the New York Museum. The external feature of these statues of various sizes is that all of them, although sculpted from the front side in a strictly frontal position, have the character of semi-reliefs. Their purpose was to stand with their backs leaned against one another or against the wall, and therefore their back side was not only left uncut, but also often represents a rough plane, as if the whole statue was flattened back to its full length. In the style of these statues, along with the Assyrian or Egyptian elements from the very beginning, a third element also appears, which can only be called Greek. Even the primitive inhabitants of Cyprus were related to the Greeks, and after the Phoenician colonization of the island from the south was followed by the settlement of the Greeks from the north. Therefore, it is quite possible that, as Brunn admits, among the artists who worked in Cyprus, there were at first very few people of Aryan origin, and that, obeying the taste of Phoenician customers, as well as due to the absence of other models before the eyes, VII Saissko-Egyptian art style and only in the VI century., Under the influence of archaic Greek art, they again gained independence. For the Assyrian epoch of Cyprus, for example, the male statue of the New York Museum is typical (Fig. 222. You can see in it the Semitic face shape, the Asian headdress, the Assyrian style of depicting hair on the head and beard, long clothes that go down without folds; but she also has a deviation from the Assyrian style: a shaved mustache, smooth muscles of the arms, small folds of the costume draped over the shoulders. The transition to Egyptian influence is represented by another male statue of the same museum.In a headdress, beard and hair on her head is still shown It is Assyrian style, but the whole body is exposed up to the hips, an Egyptian sheen covers the waist, and an Egyptian decoration is worn around the neck. The third male statue of the same museum has the Egyptian imprint. Her bezborodo face is framed with an Egyptian haircut; clothed in a sleeveless shirt, tight to the body (Fig. 223). In the later Cypriot statues of Egyptian character one can see how gradually the corners of the mouth and eye begin, in the manner of Hellenic archaism, from be tempted, chin protrude, high headgear and hairstyle fade. Finally, there are figures completely Greek in type, clothing and its folds, such as, for example, one of the male statues of the Louvre Museum (Fig. 224).

Fig. 220. Frieze of the Bible temple. With photos of Girodon

Fig. 221. The sarcophagus of Ehmunazar. With photos of Girodon

In Phenicia crafts flourished. Until the very era of the Roman emperors, Phoenician fabrics were famous, especially those dyed with the sap of purple snails; No less famous and thin Phoenician products from colored glass, which although represented from the VII century. the imitation of the Egyptian, but two thousand years later laid the foundation for the glass production of Murano. Pottery was less significant in Phenicia and Cyprus. Nevertheless, historically, Cypriot ceramics is extremely interesting, since we, together with Obnefashchem Richter, are able to trace it from the earliest prehistoric times. And here, in vessels imitating pumpkins and wicker baskets, we find the original forms of ceramics. Then one after another comes a variety of styles that can be likened to the neolithic style of Europe, prehistoric Egypt, the most ancient one that dominated the island of Fera and Amorgos, as well as the developed Mycenaean.

The last, Dauphinikian stage is represented by vessels painted with red and black colors (from 1200 to 900 BC), the shards of which were found in Kition together with iron objects, and which are located in the Grassi Museum, in Leipzig. In some Cypriot vases of the Phoenician epoch, here and there the influence of the modern dipilonic style with its geometric division of the surface into fields is noticeable. However, there are concentric circles, rosettes, Egyptian wreaths of lotus flowers and buds, some ineptly executed figures of humans and animals, sometimes even friezes with images of animals. However, Cypriot ceramics never reached the highest point of development.

Fig. 222. Assyrian style Cyprus statue. According to Chesnola

The more important role was played by the Phoenician-Cypriot hardware, especially shields and flat bowls, decorated with concentric circles of symbolic ornaments and images of celestial and terrestrial winged creatures, rows of animals, human figures, hunting and war scenes; both of them are sustained in a distinctly oriental style with the imprint of the Egyptian and Assyrian influences, either separately or together. Shields made of bronze, found in the grotto of Zeus on Ida and described by Galberger and Orsi, are kept in the Kandia Museum.

Fig. 223. Cyprus statue in Egyptian style. According to Chesnola

From Cyprus there are also remains of a bronze shield with a simple ornament (Louvre Museum). The Phoenician shields of the British Museum and the Gregorian Museum in the Vatican are mined from Etruscan tombs. Silver and bronze bowls of this kind are decorated with images of a part of knockout, part of carved work. The silver bowl of the Kircher Museum in Rome (Fig. 225), in which the image in a completely Egyptian spirit is accompanied by the Phoenician inscription, comes from Palestine; from the same place, gilded silver bowls of the same collection, on the outer edge of which the adventures of a king in hunting are depicted in Egyptian style, are obtained. В Цере, в гробнице Регулини-Галасси, сокровищам которой Грегорианский музей в Риме преимущественно обязан своим значением, найдена серебряная чаша, на которой по наружному краю идет полоса с изображением пеших и конных воинов, средний круг представляет охоту на львов, а внутренний – нападение двух львов на быка. В Дали, на Кипре, найдена вызолоченная серебряная чаша Луврского музея, на которой изображены львы, грифы и крылатые сфинксы, сражающиеся с людьми. Все эти произведения имеют большую важность, так как благодаря своему распространению при помощи финикийской торговли по всем берегам Средиземного моря немало содействовали перенесению на них восточных художественных форм. Греческого и даже микенского в этих изображениях уже нет почти ничего, и мы находим в них единственно египетские и ассирийские мотивы, а потому считаем совершенно напрасным искать место их изготовления, как делает это Брунн, на острове Кипр, а не на континенте. Еще в "Илиаде" (гл. XXVIII) описывается серебряная чаша, представлявшая "сидонян искусных изящное дело":

The men of her Phoenicians, swimming in the hazy Ponte,

They brought to Lemnos a sale, but they offered Foas as a gift.

The ships of the Phoenicians transported "on a hazy Ponto" not only goods, but also settlers to the far west of the then known world. The most famous of the Phoenician colonies, as you know, was Carthage, founded in 800 BC. e. Phoenician settlements were also located on the islands of Sicily, Sardinia and Malta. From pre-Roman time in Carthage, very few monuments survived, with the exception of the ruins of the city walls. But the mixed Egyptian, Phoenician, Greek and Roman style images that survived the North African tombstones and fragments of various products, was weak and had no effect. From the Phoenician temples in Malta (Gagiar-Kim) and the small neighboring island of Gozzo (La Jiganteia), only remnants of the walls of cyclopean, polygonal, megalithic masonry, by which only the plans of these structures can be discerned, are preserved. They have a remarkable ovate rounding of individual chambers and the use of stone blocks of amazing size, from which the doors are cut at the entrances and in the aisles.

Then the original Nuragens in Sardinia. These are tall round structures in the form of truncated cones, composed of approximately horizontal rows of roughly hewn stones; the massive wall of the colossal thickness of such a structure contains one, and sometimes several rooms, similar to a beehive and interconnected by passages and staircases; their ceiling is vaulted, formed by rows of stones moving forward one above the other. The remains of such buildings have been preserved by the hundreds, and many of them, connected together by walls, sometimes, for example, in Orta, form (after the restoration of Sipieu) something like a small fortress; they had previously been considered tombs or temples, but now everyone unanimously acknowledges that they served, if not dwellings, then treasuries or shelters in case of danger. Talayots on the Balearic Islands, having exactly the same device, can be counted among such structures. The Nuragens and Talayots were formerly considered works of the Phoenicians, but now they are attributed to North African settlers of the pre-Carphagian era, who, as the numerous objects found here, prove, had trade relations with the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians. Indeed, the purely Sardinian bronze figures of the inhabitants of Nuragens in the museum of Cagliari, representing for the most part warriors or hunters, by their naturalism and immediacy, and at the same time by their barbarous simplicity and angularity of quite primitive work, have nothing in common with the Phoenician style.

Fig. 224. Cypriot statue in the Greek style. With photos of Girodon

The influence of Phoenician art spread to the east no further than the coastal line of Syria. Here lay Palestine, the holy country of the Old Testament. Particular attention raised by the construction of the Jerusalem temple in a number of issues of the history of Hebrew art, due to the influence of the religion of the Jews on the spiritual life of mankind. Meanwhile, with the exception of some remnants of the wall on Mount Zion, or Moriah, about which antiquity is still under discussion, there is almost no trace of the Jewish art of the pre-Alexandrian era. The description of the temple and palace of Solomon in the Third Book of Kings (chap. 5-8) leaves no doubt that Solomon commissioned the construction of these structures by the Phoenician architect. The king of Tyra, Ahiram (Hiram), between 1000-900 BC e., satisfying the request of his friend Solomon, put at his disposal an unlimited number of stonecutters and carpenters; quite accidentally, Hiram was also called by the foundryman, whom Solomon had summoned from Tire, “he possessed the ability, the art, and the ability to make all sorts of things from copper” (3 books. Samuel, ch. 7, art. 14). The temple of Solomon represented in the plan three courtyards. In the outer wall surrounding it was a front yard accessible to one and all, called the "court of the pagans". Another, higher wall with a copper gate, facing east, south and north, was surrounded by a second courtyard - the "Jewish yard". The third wall with the gate located against the gate of the second wall enclosed the more elevated "courtyard of the priests." On the back, the western side of this courtyard stood the temple building, consisting of a tower-like gate, open porch, high "sanctuary" and cubic "holy saints", where the Ark of the Covenant with the tablets of commandments was kept. The foundation and walls of the walls were made of large stone blocks, the walls of the temple were made of ashlar; the columns of the courtyards, the roof and the wooden lining of the sanctuary were cedar, and the floors of the fir tree. But all these materials were covered with a rich lining of sheet gold. The Third Book of Kings (ch. 6, p. 29) states: "On all the walls of the temple he made carved statues of cherubims and palm trees and blossoming flowers, all around and without"; A supplement to this directive is the vision of Ezekiel: "Cherubim and palm trees were made: there is a palm between two cherubs, and each cherub has two faces" (ch. 41, v. 18). Who, reading these words, will not think about the Mesopotamian sacred tree with winged figures on its sides? Here the ancient Babylonian traditions, brought to Chaldea from Ur by Abraham, could play some role. On the contrary, the architecture of the temple, no doubt, used mainly Egyptian forms for the very fact that they were the only ones that the Phoenicians owned in such an ancient time, before the Assyrian conquest. Attempts at the restoration of the temple, under which Sipiu accepted this circumstance, in any case, should be considered no more than arbitrary fabrications.

Fig. 225. Phoenician silver bowl, found in Palestine. By Perrot and Shipie

Palace of Solomon is described somewhat more accurately than the temple. Columns of cedar wood played a major role both in the entrance hall and in the galleries of the palace, as well as in its hall, which says: "And the house of cedar covered over the countries of the pillars, and the number of pillars is four and five, fifty lines each." Of the foundry works of Hiram in Jerusalem, two are especially mentioned: firstly, a pair of ornamented "pillars" at the entrance to the temple, 14 cubits high, with capitals 5 cubits, called Jachin and Voas; some consider them to be free-standing columns, others to be parts of the structure; secondly, the so-called “sea of Liano” is mentioned in the priests' porch - a giant water basin in the shape of a flat bowl, supported by ridges of 12 bulls arranged in a circle and turned outwards with their heads. Cherubs inside the "holy of holies", 10 cubits high, with wings 5 cubits long, were an olive tree and gilded. Whether they had a human or bestial image, or whether they were two-breed creatures, like cherubs in the vision of Ezekiel, is unknown. In any case, these winged sculptures of the Jerusalem temple contributed to the fact that the fantastic images created by Mesopotamian art, varied in various ways, remained in art to our time.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)