In the VI. the most influential of the Greek states were ruled by tyrants, diligently, with great artistic flair, like Pisistratos in Athens, who adorned the cities with magnificent buildings, under the shadow of which all the arts reached the first strict chaste flourishing. The prevailing dominion of the rich Lydian kings, of which the last was Creuse, spread over the entire Hellenic coast of Asia Minor and inherited from them by the Persians, did not in the least prevent the flowering Ionic cities of this coastal zone from taking an active part in the development of Hellenic art. But the real starting points of the Greek artistic life of this century were the islands: Samos, where the tyrant Polycrates, Chios, Naxos and Crete reigned.

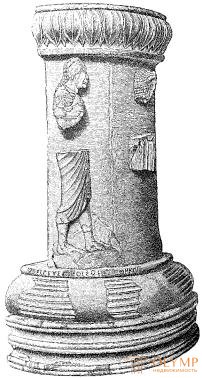

Fig. 277. Column of the Temple of Ephesus in Artemis. By Overbek

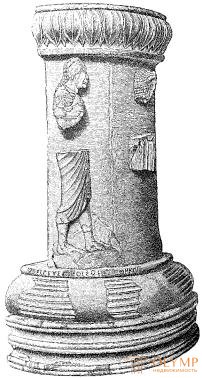

The first place in the history of this development belongs to architecture, to the works of which is adjacent most of the creations of other branches of art. Royk and Theodore from Samos, considered inventors of the Greek copper casting and working for Croesus and Polycrates, were apparently architects, sculptors and goldsmiths at the same time. We are most aware of the activities of Roic, as the builder of Geroon on Samos, "the most ancient of the Ionic stone monuments," as Durm called him. It was probably a temple on ten columns in each of its narrow sides and with a corresponding double circumferential colonnade (dipter) or, perhaps, with only one outer row of columns (pseudo-dipter). From it survived only fragments of columns, bases and capitals. Theodore was invited as an architect to both the Ionic continent of Asia Minor and the Doric Peloponnese. In Sparta, he built the round building of Skias. In Ephesus, he participated as an adviser in the tab of the famous temple of Artemis. The builders of this miracle of art in its original form are Kersifron and his son, Metagen. However, it was completed only 120 years later, much later than the Persian Wars, by other artists, then, in 356 BC. e., burned by the insane Gerostrat and restored in a new form under Alexander the Great. The structure of Herseiffron is a monumental dipter of the Ionic style. The inscription on the fragment of one of its huge marble columns certifies that part of it was donated by Creuse; the same fragment, which is stored in the British Museum, in London, proves that the columns of the first Temple of Artesis in Ephesus were the so-called columnae caelatae, whose bottoms were luxuriously decorated with plastic images (Fig. 277). Plastic on the columns, of course, had a strict ancient character. The abundant dissection and horizontal grooves of the high bases of these columns, as well as the columns of the Samoan Gereon (fig. 278), correspond to the ancient Ionic style. But by the general appearance of these two temples of a fully developed Ionic style, we must consider them to be completely mature, masterful works of architecture. If we take into consideration that the Temple of Ephesus was 127 meters long, that its columns were 18 meters high and that, consequently, its length inside was approximately the same as the Cologne Cathedral, while the height was equal to the height of the aisles of this cathedral, then it is clear why the ancients already for one huge size attributed it to the wonders of the world.

Fig. 278. The base of the column of the temple of Hera on about. Samos. By Baumeister

The temple of Zeus under the mountain of the Athenian Acropolis, one of the greatest Doric monuments of the 6th century, was built by Antistat, Calleskhr, Antimahid and Porin. The overthrow of the sons of Peisistratus (in 510 BC. E.) interrupted this building, and it was resumed only about 174 BC. eh., but in a different style. The builders of the temple of Athena in the Acropolis of Athens, a Doric building, famous for its antiquity and called Hecatompedon for its cella, which was 100 feet long, are unknown. Both short sides of this temple were decorated with porticos. Behind his long cella, divided into three naves, was square in terms of the despair. He was surrounded by a simple colonnade. This temple was destroyed during the Persian Wars.

The era of the great Doric temple of Apollo at Delphi, the architect of which is called the Corinthian Spinfar, dates back to the Peisistratians. At the turn of the VI and V centuries and later in Sparta, worked as an architect and sculptor Gitiad, the main works of which are considered the temple and the statue of Athena of Chalkioikos. This epithet of the goddess shows that her temple was copper; in any case, it was lined with sheets of embossed embossed work, described by Pausanias and giving the structure great gloss and elegance.

Fig. 279. Aegean temple of Athena. From the photo

Regarding Greek painting in the VI century, literary sources provide relatively little information. On the contrary, the painting of the vases of this epoch abounds in the names of artists and "signed", that is, supplied with the artist's name, and drawings. However, before turning to this kind of painting, we must dwell on the testimony of literary sources about painting and consider its few remaining monuments.

Fig. 280. Stele Lisey. By Lyoshka

Ancient writers report that painting owes its origin to the desire to fix the shadow cast by a living creature on the surface of a wall or on a board; some artists sketched the outline of the shadow, and thus linear painting was born, soon replenished by drawing internal lines; others filled the entire space inside the contour with one paint and thus marked the beginning of monochrome painting, which some artist enlivened by adding red paint to it. One glance at the most ancient vase painting, with which we are already familiar, convinces us that painting in some contours and painting with filling out contours with paint in the beginning really went hand in hand; in the same way, we already know that the black paint of monochrome painting was first of all joined by red. The inventor of this increase was probably Corinthian Ekfant. Further progress in painting associated with the name of the Athenian. Evmara (or Evmaresa). This artist was the first to distinguish male from female in all ages and was able to characterize every kind of profession. Of course, here we are talking only about the image of female figures in white, and the men in black paint, as we have already seen in the transitional style of vase painting (see Fig. 260, b). Much more important are the improvements attributed to Cimon Cleonsky, who worked not only in the 6th century, but also at the beginning of V. Pliny said that this master, using the successes achieved by Evmar, invented oblique images (obliquas imagines). These words should be understood, contrary to all other interpretations, in the sense that Cimon began to reproduce the head, chest, torso, arms and legs in the correct contraction, and perhaps correctly draw the human eye visible from the side, which is painted on vases for a long time after the Persian Wars, he was depicted en face, even with the profile of the head. The suggestion of the ancient researchers that the expression "obliquas imagines" means the image of figures in three-quarters of a turn, although plausible, can be disputed. Klein sees in this expression only an indication of the combination of silhouette painting, which black-figure vases represent to us, with contour painting, what it is on red-figure vases. Further, Pliny the Elder is made clearer by saying that Cimon first began to depict differences in faces and glances back, up and down, outline the details of body members, mark veins on its surface, transmit folds and bulges of clothing. All these improvements, as we shall soon see, gradually penetrated into the painting on the vases.

Painted attic clay boards of this era make up the transition to painted clay vessels, with which they are quite similar in style. According to the Girshfeld, to the sixth century, even its middle, attic clay slabs from the Berlin Museum, found in 1872 near the Dipilon Gate, belong. Although they came to us in the wreckage, it turned out to be possible to restore them to their former form. These are large paintings depicting funeral rites; they stretch from board to board and probably served as decoration for the tomb. The profession - exhibiting the body of the deceased, his mourning, the gathering of his loved ones in mourning peace, the procession of horsemen and chariots drawn by four horses, all this is perfectly in the style of the middle pore black-figure vase painting. As in this style, women are depicted as white, with almond-shaped eyes, painted en face with a strictly profiled head position; Men are painted in black paint, with eyes in the form of circles, on both sides of which they are added along a small line. The internal lines of the picture give a lot of life to the silhouettes, still as if drawn from the shadows and still sharp, although they have an understanding of nature. The monochrome general background is varied in places with glue paints; White, yellow and red paints of various shades form a harmonic color chord. A clay board with a similar burial scene, located in the Louvre, of later origin.

Fig. 281. Bowl of Arkesil. By Ray and Colignon

The earthen vessels of the time in question testify to the gradual development of the graceful feeling of the Greeks by their own forms, which gradually pass from ancient spherical outlines to more slender and beautiful ones. The connection between the legs, torso and (where required) the neck of the vessel and the prefix to it with one or several handles are distinguished by an impeccable taste that is exemplary for any era, in each case correspond to the purpose of the vessel and have pleasant forms for the eyes. Amphoras were intended for the storage of liquids, hydrias for carrying water, craters for mixing liquids, and katifs for drawing. A mug (oinochoe) was used for pouring, a cup (kylix) or a cup (kantharos) was used for drinking.

Lekife (lekythoi) - slender jugs with a handle, used to store ointments or sacred oil, which was used during funeral ceremonies. Ariballa (aryballoi) - bloated in the middle of the vessels of the same kind.

The fact that the copies that have reached us for the most part were not intended for everyday use, but were made specifically for the decoration of tombs, does not in the least diminish the artistic and craft significance of their forms.

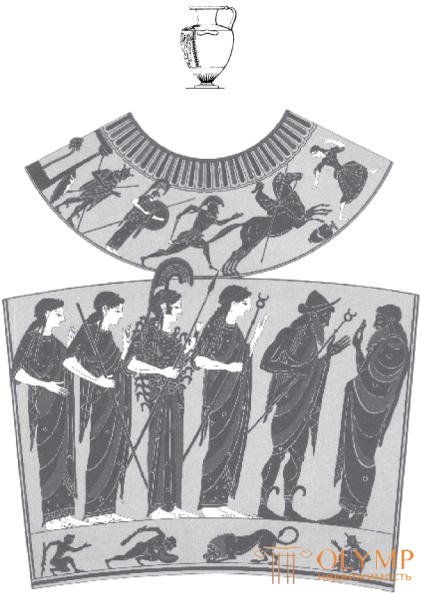

The 6th century is a classical epoch of black-figure painting on vases, as well as the time for the development of painting with red figures, the first, harsh, sharp flourishing of which continued until the Persian Wars. In the VI. Athens became the center of the production of earthenware vases; They were competing with them in this field of Chalcis in Euboea, perhaps at this time also in Navkratida in Egypt; Corinth tried to keep on the same level with them, but Athenian VAZ factories quickly surpassed all the others in their craftsmanship, and it was in these factories that black-figure painting first of all entered the path of strict style. But at this time in more distant colonies, painting on vases very naively sought to revitalize their images, without breaking their connection with antiquity, as evidenced by the example of the Arkesilaus Cup, the Paris Mint (Fig. 281). Arkesilay, king of Cyrene, a Greek city in Libya, sitting on a ship, is watching the weighing of the sylphion, which is immediately loaded into the hold. In the figures of workers there is a lot of life and movement, albeit disorderly. The eyes of men, with a profile turning of the heads, are still en face painted and have an almond shape.

Fig. 282. Vase Francois. Side view. From the photo

Собственно историю развития греческой живописи на вазах можно проследить всего яснее на вазах с подписями художников, которые встречаются почти исключительно в Аттике. Описанием этих ваз занимался в особенности В. Клейн. На первое место в аттической чернофигурной вазовой живописи должна быть поставлена ваза Франсуа, названная так по имени открывшего ее ученого и находящаяся во Флорентийском музее (рис. 282). На ней значатся имена Эрготима, гончара, формовавшего ее, и Клития, художника, которым она расписана. Это большой сосуд для смешивания жидкостей, сверху донизу покрытый изображениями мифологического содержания; начав с брака Пелея и Фетиды, художник проводит нас в этих изображениях через различные циклы мифов, воспроизводит сцены войны и ссор, мира и спокойствия. Расположение рисунков параллельными рядами придает им древний и восточный характер; такое же впечатление производят и нижняя полоса на туловище вазы с ее пальметтными деревьями среди фигур сфинксов и грифов, и изображенная на ручках крылатая Артемида, удушающая льва (так называемая персидская Артемида). Но все эти мифологические рисунки представляют уже вполне развитый плоский стиль чернофигурной живописи во всей его, еще нередко неповоротливой, резкости, но и со всей внутренней оживленностью.

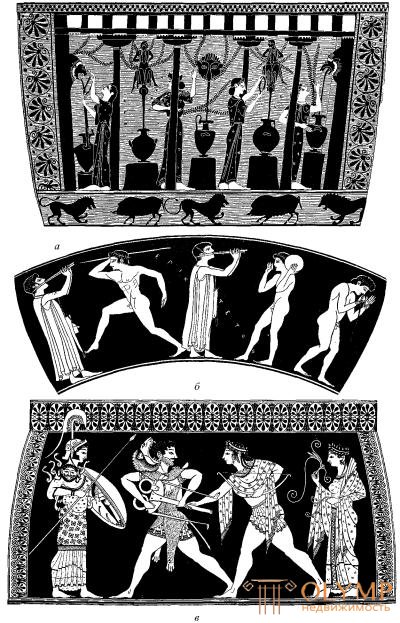

Fig. 283. Ancient Greek painting on vases. By "Antiken Denkmdler" (a) and Gerhard (b, c)

Fig. 284. The battle of Hercules with the Nemean lion. Painting Exekiah. According to Gerhard

Next to the early archaic style of vase Francois should be given a place primarily a strictly archaic style. The yellowish background of the clay, due to the admixture of paint to it, receives a beautiful red tone, on which figures, painted with shiny black paint with a pattern scratched inside and passed from above with glue paints, protrude. The drawings on the vases of this style represent all those ancient features of the profile positions, the outlines of the body and the shape of the eyes, with which we have already become acquainted. The belly of human figures is still skinny, and the hips are wide and massive. Clothes are covered with various patterns, but there are still few folds on it. The figures presented in a calm position, different stiffness; cutting movements. Among the gods depicted, the main role is played by Dionysus, the god of wine, among the heroes - Hercules. But the entire everyday life of the Greeks is reproduced in these drawings: we see women at the well, young men engaged in gymnastic exercises, hunting (fig. 283), competitions in running, feasts, dances and musical entertainment. On the throats, legs, edges and handles of vessels are ornaments again. The arc-shaped friezes with three-layered color profiles still resemble Egyptian patterns, although the flowers are slimmer, their antennae are more elastic. The stalks of ivy on the edges of the vessel are already a Greek innovation. Palmettes on the handles have already quite Greek grace and lightness, although they are still with strict symmetry. The main masters of strictly archaic vase painting in Attica were Exceky and Amasis. Exekiah's amphoras can be seen in the Louvre, the British Museum and the Berlin Antiquarium; Amazis amphorae - in the Paris Müntz Office and the British Museum. Fig. 284 copied from the Berlin amphora Exekiah.

Fig. 285. Ancient Greek painting on vases of black-figure style: Achilles pursuing Troilus and Poliksen are at the top ; in the middle is the judgment of Paris; below - the battle of Hercules with the Nemean lion. According to Gerhard

The style of black-figure drawings on vases gradually, without losing the main distinguishing features of archaism, becomes easier and more free. Apparently, the Asia Minor Ionic influence is reflected in it. Forms are made more rounded, folds appear on clothes, palmettes on handles lose their strictly symmetrical arrangement, and fluttering birds appear between their stems and leaves, which is an important innovation. Among the names of artists, the names of Haritea, Timagora, and Tikhiya deserve attention . But the main master of the obsolete style of black-figure painting is Nikosfen. To 68 black-figure vases of his work, which were known to Klein, one should add another bowl with figures, partly black, partly red, and three vessels, decorated with red figures alone. The small amphoras of this master are especially numerous in the Louvre. But the later Attic style with black figures can be much more clearly studied on numerous vases not equipped with the names of artists: such are, for example, the vase from the Berlin museum depicting the battle of Hercules with the boar and the famous vases depicting the court of Paris and putting on a harness on four horses. In fig. 285 - a wonderful vase, the overall decorative impression of which is due to the excellent distribution of four colors.

The heyday of painting on vases is noted in red-figure drawings. The painting of the most ancient of the red-figured vases responds to the still angular style of the later black-figure painting, characterized by the depiction of specialized positions. Thanks to the studies of Studnichki and others, we know that this strict red-figure style belongs to the time that preceded the Persian Wars and even the V century BC. e.

If we accept that the origin of this style, as Klein pointed out, is in connection with the aforementioned changes made by Cimon Kleonski to art, we must still assume that Cimon’s art was more mature and free than the art of Epictetus, the main Attic master. the first strict red-figure vase painting. Now the entire background of the vessel is covered with shiny black lacquer paint. At first, the background of the vessel was scratched for black pieces, but soon only the figures on the red clay background began to be scratched. Internal drawing is executed by means of a brush with gentle strokes. Where, when depicting black hair on the head, significant black spaces would merge with a black background, the contours of red paint are drawn.

Epictetus along with Pamphai, who also produced black-figured hydrias and bowls, Gishil, Helis, Epilic, Kahrilion and other masters, most of whom, like Epictetus, also produced, although in small quantities, vessels with black and red figures. called epiktetovsky cycle of painters, their favorite works were cups. Red figures appear first on the external pattern of bowls and with large eyes, as on black figure bowls, and resemble the ornamentation of primitive peoples. Individual figures are usually depicted, movements of which adapt to the roundness or curvature of a given space. “In one place,” Klein said, “they carry, lift, crawl, run, crouch, dance, jump; in the other, shooting and throwing, chisel and chisel work, drawing water, playing music, and all this only to to justify those bends of the human body, which the bottom of the cup, as it were, require. " Of the red-figured vessels of the work of Epictetus himself, in the Louvre Museum there is a bowl, on the inner surface of which a drunken young man is represented, and outside, between the eyes, there is a warrior in a helmet and an arrow from a bow. Many bowls and plates of Epictet's work are available in the British Museum. In the Berlin antiquarian you can see the bowl with the signature of this master; on its inner surface is depicted Silenus with fur, and on the outer side - physical exercises of young men (see Fig. 283, b). Outside the epictet cycle stands Andokid, the eraser of the amphora of the transitional epoch from the red-figure to the black-figure style; his red-figure amphora depicting the abduction of the tripod by Hercules is located in the Berlin Museum (c); she is very instructive for the history of the development of Attic painting in the VI century.

Later works of art, richly decorated with reliefs of mythological content and described in detail by Pausanias, belong to not-anonymous artists. The throne of Apollo in Amiklah, near Sparta, was the work of Bafikla of Magnesia. He clearly shows us that around the sixth century, the art of Asia Minor influenced Peloponnesian art. This throne, as became known through the research of Reichel, is probably one of three primitive monuments that were honored as the seats of an invisible deity. Bafikl renewed his wooden frame and inlaid it with plastic bronze images of knockout work. The statue of Apollo, 15 meters high, was more ancient than the throne, for, according to Pausanias, who called it "a similar copper column", was something not connected organically with the throne. The question of how the plastic images described by Pausanias were placed on the throne, aroused lengthy disputes in which opinions diverged significantly. We have to be content with the data of the Brunn restoration, according to which the main reliefs were divided into three series, nine in each, all of which corresponded to one another in size and content as well as the reliefs on the box of Kipsel. In particular, we can imagine their style, as Furtwangler does, similar to the style of the later black-figure vases, probably with a noticeable Ionic shade, and therefore, with a greater abundance of folds on clothes and a cleaner styling of the nude body than on the chest Kipsela.

Among the sculptors of this era, we meet Roik and Theodore of Samos, whom we already know as architects. They are believed to have started a foundry in Greece. Of course, small massive figures cast from bronze had already been made before them, so in this case we are talking only about introducing castings of empty statues around the solid core. Rojku belonged to a bronze female figure, called, probably, “The Night” and standing in Ephesus, near the temple of Artemis. Of the works of Theodore, however, predominantly gold items are known, for example, a ring made for Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, and a silver mixing vessel that contained 600 amphorae and donated by Cres to the Delphic oracle.

A contemporary of these artists was, as it should be, Smilid, who owned the wooden image of Hera in her Samos temple. The assumption about the origin of this artist from Aegina is based only on the fact that his wooden statue had in an ancient way a stretched pose and legs closed together. Such sculptures were called the Aeginian statues, in contrast to the ancient statues, which were distinguished by a great movement and were called Attic or Daldal. The image of Hera on Samos coins gives us a rough idea of the ancient personification of this goddess.

Fig. 286. Delos Nika. From the photo

The most significant of the oldest Greek marble sculptors, according to legend, were the natives of the Ionic island of Chios. Among them is mentioned the whole family of artists: Melas, his son Mikkiad, grandson of Arkherm and great-grandsons of Bupal and Afenis. About Arkherme it is reported that he first portrayed Nick, the goddess of victory, winged. Therefore, it is not surprising that when the base of a column with the names Mikkiada and Arkherm was opened on Delos and the winged Nika, made of Parian marble in a very ancient style, was not far from it, they assumed that they had found the original work of Arkherm. However, Trey proved that this marble statue has nothing to do with the above inscription. Nevertheless, nothing prevents us from imagining the winged Nike Arherme exactly as the marble statue found on Delos and now in the main museum in Athens (fig. 286). The goddess is depicted running, but her movement resembles a fall on her knees. Since such a pose could be depicted better from the side than from the front, the lower part of the body of the goddess forms an almost right angle from the top. This figure belongs, therefore, to those few works to which Yuli Lange already pointed, and which in the period under consideration represented a retreat from the law of frontality. Regarding the style, the head of this statue resembles closely the head of the Olympic Hera (see fig. 270), although there are no trace of the planes produced by the chisel of the ancient style. The bust is fairly flat and shapeless. Beneath the folds of clothing are well-shaped hips. That Arkherm was one of those Ionic masters who transferred their art to Athens is proved by a pedestal found in the local acropolis with the name of this artist. His sons, Bupal and Afenis, who lived around 540 BC. e., already enjoyed universal fame. Emperor Augustus transferred the fronton group of the work of these two brothers from some unknown Greek temple to the pediment of the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill in Rome. Therefore, it can be considered possible that the kneeling amazon found at the Villa Ludovisi in Rome is nothing but a fragment of this original work; however, its forms seem to us not rude enough for the 6th century.

But the first truly famous sculptors of marble are Deepope and Skillid; they came also from one of the Greek islands, probably from Crete, and worked in Peloponnese, mainly in Sicyon. In addition to the marble statues for the temples of this city, they produced a group of wooden ivory-lined statues for the Dioscuri temple in Argos. Therefore, these artists, like Smilid, are counted among the founders of the chrysophyletic technique; numerous students spread their receptions in the cities of the Peloponnese.

Fig. 287. Giant. One of the gable sculptures of the treasury of the Megarians in Olympia. By Trey

The disciples of Deeppoin and Skillida also include Clearch of Samos, who is usually called Clearch of the Regional, because he moved to the Region in southern Italy. Since the Region lay across from Sicily, Overbeck thought it possible that this artist had spread the style of the School of Depoyna and Skillida in Sicily. Of course, this is nothing more than a guess; Be that as it may, but the reliefs of the ancient metopes of the Selinunte Church F, located in the Palermo Museum, are obviously related to the gable sculptures of the treasury of the Megarians in Olympia. Only the lower halves of the two plates have survived. On each of them was depicted a goddess throwing a giant to the ground. On one of them, the giant falls to his knees while still very strong

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)