Architecture

In the 15th century, art began to develop in Germany in cities that had just begun to flourish even more decisively than in other European countries.

World trade, whose roads between the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea and the North Sea continued to pass through Germany, raised the well-being of cities; more sophisticated life needs made their inhabitants inventive; on the basis of urban craftsmanship and industry, from which came the world inventions of book printing and other reproductive arts, architecture, sculpture and painting also awakened to a new life. The goldmine of the craft, which poetry has withered to, descending from a love song (Minnesang) to an elaborate song (Meistersang), has communicated to the visual arts that healthy workshop training, without which they cannot do because they are created with their hands; it cannot be denied that, according to their origin, it is in Germany that quite often remains a touch of their characteristic coldness and rudeness. But the wealth of strong and tender, bold and intimate feelings and moods inherent in the German people raises the German art of this time all the more above the craft of stupidity, into the realm of spiritual beauty.

Although architecture in Germany was quite often bourgeois-transparent and whimsical, not serious, but it was here that she took part in a spiritual impulse that inspired the coarse realism of the visual arts. If the realism of time is reflected in the new unit of the new parish churches, which has now appeared alongside the former cathedrals, the whole community, especially in the union of the choir with the longitudinal body and in the exclusion of the transept, then the desire for light does not only appear in the preference of the churches of the hall system, but also in the construction of church towers ascending to heaven, nowhere reaching such a height as in Germany. Considered from the Gothic point of view, the German churches of the 15th century hall system undoubtedly represent a step back, as their star-shaped and reticulated vaults, openwork decorations in the form of flames (nicknamed "fish bubbles") and rounded arches (nicknamed "donkey spins") are mostly drier than in Western Europe. At the same time, in terms of practical and religious architecture, they represent a movement forward. We are not inclined to even refer to the most advanced late Gothic constructions of this kind in terms of volume, together with some well-known researchers, to be Renaissance-style constructions, since this in itself follows from our understanding of the term “Renaissance”.

Of the masses of stonemasons and ordinary craftsmen are now allocated and architects. Along with Cologne, Swabian architects also led the movement. Ulrich of Enzingen (died in 1419), to whom Karstanen dedicated the book, worked in the first two decades of the century. We meet him in Ulm, Strasbourg, Esslingen and Milan to the highest tasks set by time.

His son Matvey followed him everywhere, and worked independently only in Bern; Matvey Boeblinger worked at the end of the century.

Fig. 366. Tower of the Strasbourg Cathedral. By Degio

The region of the Rhine was not equally rich in artistically significant new buildings; the proximity of France is evident, perhaps, in the fact that the churches of the hall system do not predominate here, as in the rest of Germany. The cathedral in Berne-on-Aar, the southern tributary of the Rhine - the creation of Matthew Enzinger, represents the basilica with pillars without a transept, with a simple choir. The skillful reticular arches of its three porches, the richly carved work of the western facade and the extremely varied stone carvings of the galleries and windows testify to the style of the epoch, as well as the plan of the skilled craftsman.

On the Rhine itself, in Strasbourg, in 1399, Ulrich Enzinger, called up from Ulm, took over the construction of the cathedral.

It was only because of the towers. The great Swabian architect decided to make only one, the northern tower of the western facade, but elevated it to an extraordinary height. Without a connection with the foundation, a slender octagonal structure rises to a dizzying height, divided into eight parts by colossal windows with keel-shaped arches and four thin twisted staircases consisting only of vertical bars (fig. 366). After the death of Ulrich, Johann Gülz from Cologne performed between 1420 and 1439. wonderful pyramidal pomeranian dog, eight of which are slanting ascending ribs which pass into the same through stairs. Not a single building in the world has overcome the severity of the stone as victoriously as in the tower of the Strasbourg Cathedral, but the natural sequence is inferior here to the artist's whim.

On the Middle Rhine, in Worms, was re-erected in the XV century. Church of Our Lady, famous for its vineyard, built in elegant proportions of the Basilica with a choral circuit and three western towers. On the Lower Rhine continued to build primarily Cologne Cathedral. Among the builders of the Cologne Cathedral, he emerged as the sculptor Konrad Kun (1452–1469). The south tower began to appear on the western facade. Around 1499 construction was still in full swing, then it gradually stopped. Of the newly built churches of Nizhny Lare XV century. deserve mention: the church of sv. Vilibrord in Wesel - a five-nautical basilica with reticulated vaults and through stone “fish bubbles”; The parish church in Kalkar is a graceful brick church of a hall system with columns. In the south aisles of the church of sv. Wilibrord in Wesel used decorative fun in the net covering of the vault, consisting in that the two rib systems are fitted one under the other in such a way that, as Dom said, “the lower one hangs freely in the form of a crystal network under a real ceiling”. This, obviously, laid the seal of the complete absence of any constructive sequence.

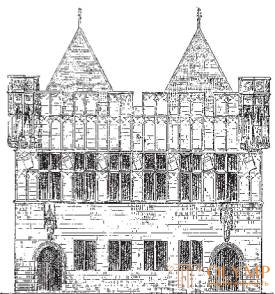

Fig. 367. Side facade of the hall "Gyurtsenih" in Cologne. By Essenwein

Among the secular buildings of the princely palaces of this time do not play any special artistic role. Description of knight castles, so picturesque with its ruins on the steep coastal cliffs, we leave to the share of Pipera, who brought to perfection the “locking”. In large cities, urban chambers are increasingly being built. The Römer in Frankfurt is a work of the 15th century. In Wesel, the facade of the town hall was now finished according to Dutch designs. In Cologne to the Old Town Hall in 1407–1414. completed the five-storey late gothic tower, but since the town hall was not sufficient for business needs and festivities of the city, in 1441 they began to build a new chamber "Gürzenich". The hall of the upper floor of this chamber, to which a straight staircase led outside, was divided in length by nine wooden columns into two naves. Outside, in calm, beautiful proportions, the side facades (fig. 367) are dissected with their vertical decorations alongside a wall of battlements and graceful through corner towers. By "Gürzenichu" adjacent merchant house Etsweiler in Cologne. Both buildings show how the secular stone buildings of the Lower Rhine assimilated the new forms of the XV century.

Sculpture

The best works of sculpture, which Germany gave during the 15th century, were surpassed only by Italian in their artistic significance, and nowhere more clearly than in German sculptural works can we trace that gradual transition from northern gothic style to strong, often devoid of style and coarse, but inspired by passion realism, which begins to become more subtle only in the transition to the XVI century. Purely plastic style, which Germany had a high degree in the transition from Roman to Gothic time, is manifested only occasionally. Trying to free themselves from the shackles that the Gothic style imposed on her, German sculpture made an alliance with painting, most clearly manifested in those unusually numerous altars, in which often only a few artistic techniques separate the picturesque sashes from the boards with painted reliefs and the wooden colored sculpture of a medium idiot . Carvers and painters often belonged therefore to the same workshops, even to the same workshops, and numerous wooden carved altars and picturesque doors came out of the workshops of famous artists, which we should therefore not imagine as carvers, but only as compilers of common projects.

For all that, the sculpture in the tree, especially for the choir seats, seemed to be enough reasons to work in its former plastic-architectural direction. Longer, of course, was associated with works of architecture sculpture in stone, but when applied to the small architecture of the departments and tabernacles, fountains, tombstones and roadside chapels, she gradually freed herself from the dependence in which she was kept by old portals and canopies of Gothic great art. Finally, the sculpture in metal, which, as always, preferably was used by small art, reached the works of large-sized bronze casting only for tombstones; in this direction, however, only a few foundries were engaged in it, of which only the Nuremberg workshop of Fischer supplied a significant part of Germany and neighboring eastern countries with artistic works.

In the Rhineland, Gothic stone sculpture on church portals has experienced secondary flourishing. The style of the first third of the XV century. we see large draped statues of apostles and seated prophets and patriarchs in the arched depressions of the southern portal of the western facade of the Cologne Cathedral. These excellent works can be attributed to the architect and stonemason Konrad Kun. The clothes here are still beautiful and calm, the heads are realistic. A rough understanding of reality, characteristic of the last third of the century, we see in groups with clothed figures (“The Adoration of the Magi”) of the portal of the chapel of St. Lawrence in the Strasbourg Cathedral, built by Jacob from Landsgut in the late Gothic style (Fig. 368); kinks and angular draperies, taken by stone sculpture from woodcarving without any meaning, are unbearable here. The more refined style of the late 15th century is reflected in the upper statues of the western portal of the Berne Cathedral, whose creator is Erhard Küng from Westphalia (after 1466). The Last Judgment on the pediment is unclear in composition, but angels and prophets in arched recesses and apostles sitting on thrones in vertical gaps are noble images pleasing to the eye.

Fig. 368. Capella portal of sv. Lawrence in the Strasbourg Cathedral. From the photo

Of the freer stone groups two figures of the Annunciation in 1435 in the church of St. Kunibert in Cologne is marked by moderate Cologne realism of the first half of the century, on the contrary, five large high reliefs of 1487 and 1488. (The family tree, the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Tomb, and the Resurrection of Christ) at the baptismal council in Worms are already influenced by the more pronounced realism formed in the Netherlands. Best of all, the development of style can be traced to the Rhine in stone gravestones. The tombs of the prelates of Mainz Cathedral, traced by us to the successes that distinguish the tombstone of Conrad von Weinsberg (died in 1396, cf. p. 419), lead us through the 15th century. In the tombstone to Archbishop Johann Nassauskomu (1419) one can clearly see clearly expressed portrait likeness, combined with calmly lying draperies; in the gravestone on the grave of cathedral dean Bernhard von Breitenbach (1497), the "similarity" is sharper, and the draperies are more angular. According to the performance, the tombstone of Bertold von Genneberg is more perfect (1504; fig. 369), but still it gives the impression of Gothic. Similarly, the development of Hermann Schweitzer’s activities in the Neckar valley to Heilbronn can be traced in Baden, starting with the excellent monument to Johann von Wertheim between his two wives, in the church in Wertheim (circa 1410) to the gravestone monuments to Martin von Adelsheim and his son Christoph (1494 and 1497) in the church of sv. Jacob in Adelsheim. Frames, platbands and canopies of all these monuments are still Gothic. Everywhere we see the same phenomenon: the intensification of realism takes place among the main medieval forms.

Fig. 369. The tombstone of Bertold von Genneberg in the Mainz Cathedral. With photos of Krost

With the art of carving, we meet almost exclusively in wooden altars, which here, as in the rest of Germany, according to the old custom, usually consist of a small number, but larger figures than in the Netherlands. On the Upper Rhine, where the Swabian school dominated, in the main altar of the Cathedral in Shura there is an excellent work of this kind, which Jacob Rousse (not Resch) from Uberlingen graduated from in 1491. In the very iconography sits on the throne of Our Lady between the saints; above in the middle is her wedding. Everything shines with gold and colors. In Alsace, where the Swabian, Burgundian and Lower Rhine influences intersected, it should be noted the altar, built in 1493 for the monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim, later decorated with the famous picturesque doors of Matthias Grunewald, artist of the XVI century. Its remains are now in the museum in Colmar. The three large figures of the saints of the middle ark still belong to the most free and full of life creatures of this kind of art. On the Lower Rhine, most of the remaining altars are of Dutch origin, but most of them belong not to the XV century's Brabant workshops, but to the XVI century Antwerp workshops. In the first place we will place the carved altars of the parish church in Kalkar; we know their masters and the years of their origin thanks to the research of I. A. Wolff and Beissel. If the masters were part even of the Dutch, namely the Dutch, by birth, then in Kalkar they would form a school. The ethnographic border between the Lower Rhine and Holland almost did not exist. It is important that the later of these altars are no longer painted. To consider that here, as in Southern Germany, these works remained unfinished for any reason, it seems to us to be unacceptable. The oldest, finished in 1455, wooden carved altar of St.. St. George of Kalkar Church is still painted and gilded, but in artistic terms it is low. The altar of the Joy of Mary, performed between 1483 and 1493. Master Arnold, no longer painted. Entirely at the end of the century belongs the magnificent kivot of the Passion of the Lord of the main altar. A rich, undyed cut woodwork was made between 1498 and 1500. Master Lyudevik performed numerous imperfect in forms, but very expressive compositions of the main iconot with a large Crucifix in the middle; Master Jan van Haldern, who was a student of Master Arnold in Zwölle, performed three images of the painter, heavy and boring in composition and unbearable because of excessive angularity and broken draperies. The altar "The Grieving Mother of God" of Heinrich Doverman in 1520 for the first time gives new forms of expression belonging to the 16th century.

Painting

The true art of the flowering Rhineland from Lake Constance to Cologne and Xanten was in the XV century. painting. In the first half of this era, the development of painting on the Upper Rhine was more successful than on the Lower, approximately in a parallel direction with the Netherlands-Burgundian art. Since 1460, however, the direct influence of such Dutch artists as Rogier van der Weyden and Dirk Bouts has been felt everywhere. Their style, moving often to a rougher, now more perfect, is technically rarely evenly sustained. But at all levels of its development, the Rhenish painting gave several amazing works that now belong to eternity.

In this epoch there was no shortage of frescoes along the entire Rhine. But since for the most part we are dealing only with the pale remnants of such works that cannot be considered typical of the artistic movement, with respect to most of them we can only appeal to the works of such scholars as Scheubler, Kraus, Ehelgeiser, Clemen and Fr . Yak Schmidt We will deal only with a few related to historically famous artists. On the Upper Rhine, we must first note the remarkable frescoes of the Cathedral of Constance. Here in the paintings in the upper sacristy, as, for example, in the touching Crucifix in 1348, there are still Gothic types with South German features. In 12 paintings from the life of St. Nicholas, attributed by us together with Gram to about 1420, stands a new, still timid Low German naturalism; in the frescoes of the chapel of sv. Margaritas depicting Christ and the Virgin Mary on thrones and Satan, thrown down from the throne, see a milder style of the Old Cologne school; Composition 1475 in the chapel of sv. Sylvester is already a sign of a realistic style, but their execution is not very subtle. Фрески из жизни св. Варфоломея в хоре собора во Франкфурте на Среднем Рейне по стилю еще относятся к переходному времени. На Нижнем Рейне сохранились изученные Шейблером многочисленные фрески этой эпохи в церквах Кёльна и еще более многочисленные остатки фресок в других художественных центрах, изученные Клеменом.

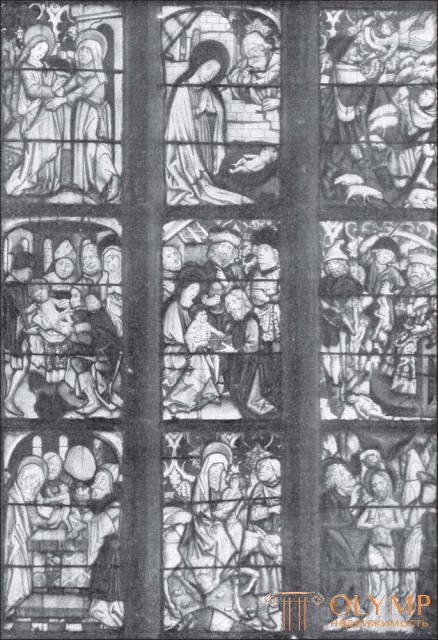

In many respects, the 15th century stained glass frescoes in the churches of the Rhineland are more interesting. On the Upper Rhine, Alsatian stained-glass windows should be noted, in which, as Robert Brooke showed, the history of all Alsatian painting is reflected more fully than even in the preserved easel paintings. The “Master from Niedergaslah”, who painted around 1400 the ten windows of the nave in Niedergasla, richly decorated with legendary images, is still influenced by ancient local traditions. On the contrary, the Burgundian-Dutch influence can be seen in the artists who painted the 7 windows in the cathedral in Tanna, which Brooke distributed among the three masters. In the “master of 1461,” whose main works are three windows in the choir of the church in Valburg (fig. 370), one feels the ability to convey a realistic perspective. Of the Alsatian painters of stained glass windows we call first of all Hans Tiffenthal from Schlettstadt,which is mentioned in 1418–1450. The suggestion that he owns magnificent stained glass windows with the life of St.. Catherine in the church of sv. George in Schlettstadt (circa 1430-1450), it is all the more likely that in 1418 he received an order in Basel to paint a picture on the pattern of paintings in Dijon, while in 1430-1450. he was the only notable artist in Schlettstadt. The style of Caspar Isenmann, "ES master" Martin Schongauer and "master of house building" Brooke was seen in the stained glass windows of the chapel of the Virgin Mary in the parish church in Zabern, on the north side of the church in Alttann, in the church of St. George in Schlettstadt and the Church of sv. Magdalene in Strasbourg. We can recognize this commonality of style, even if we did not consider it strong enough to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.that he owns magnificent stained glass windows with the life of St. Catherine in the church of sv. George in Schlettstadt (circa 1430-1450), it is all the more likely that in 1418 he received an order in Basel to paint a picture on the pattern of paintings in Dijon, while in 1430-1450. he was the only notable artist in Schlettstadt. The style of Caspar Isenmann, "ES master" Martin Schongauer and "master of house building" Brooke was seen in the stained glass windows of the chapel of the Virgin Mary in the parish church in Zabern, on the north side of the church in Alttann, in the church of St. George in Schlettstadt and the Church of sv. Magdalene in Strasbourg. We can recognize this commonality of style, even if we did not consider it strong enough to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.that he owns magnificent stained glass windows with the life of St. Catherine in the church of sv. George in Schlettstadt (circa 1430-1450), it is all the more likely that in 1418 he received an order in Basel to paint a picture on the pattern of paintings in Dijon, while in 1430-1450. he was the only notable artist in Schlettstadt. The style of Caspar Isenmann, "ES master" Martin Schongauer and "master of house building" Brooke was seen in the stained glass windows of the chapel of the Virgin Mary in the parish church in Zabern, on the north side of the church in Alttann, in the church of St. George in Schlettstadt and the Church of sv. Magdalene in Strasbourg. We can recognize this commonality of style, even if we did not consider it strong enough to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.George in Schlettstadt (circa 1430-1450), it is all the more likely that in 1418 he received an order in Basel to paint a picture on the pattern of paintings in Dijon, while in 1430-1450. he was the only notable artist in Schlettstadt. The style of Caspar Isenmann, "ES master" Martin Schongauer and "master of house building" Brooke was seen in the stained glass windows of the chapel of the Virgin Mary in the parish church in Zabern, on the north side of the church in Alttann, in the church of St. George in Schlettstadt and the Church of sv. Magdalene in Strasbourg. We can recognize this commonality of style, even if we did not consider it strong enough to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.George in Schlettstadt (circa 1430-1450), it is all the more likely that in 1418 he received an order in Basel to paint a picture on the pattern of paintings in Dijon, while in 1430-1450. he was the only notable artist in Schlettstadt. The style of Caspar Isenmann, "ES master" Martin Schongauer and "master of house building" Brooke was seen in the stained glass windows of the chapel of the Virgin Mary in the parish church in Zabern, on the north side of the church in Alttann, in the church of St. George in Schlettstadt and the Church of sv. Magdalene in Strasbourg. We can recognize this commonality of style, even if we did not consider it strong enough to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.he was the only notable artist in Schlettstadt. The style of Caspar Isenmann, "ES master" Martin Schongauer and "master of house building" Brooke was seen in the stained glass windows of the chapel of the Virgin Mary in the parish church in Zabern, on the north side of the church in Alttann, in the church of St. George in Schlettstadt and the Church of sv. Magdalene in Strasbourg. We can recognize this commonality of style, even if we did not consider it strong enough to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.he was the only notable artist in Schlettstadt. The style of Caspar Isenmann, "ES master" Martin Schongauer and "master of house building" Brooke was seen in the stained glass windows of the chapel of the Virgin Mary in the parish church in Zabern, on the north side of the church in Alttann, in the church of St. George in Schlettstadt and the Church of sv. Magdalene in Strasbourg. We can recognize this commonality of style, even if we did not consider it strong enough to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.to finally establish that the designs of these stained glass windows were made by the artist himself.

On the Lower Rhine, one should note the surviving stained glass windows of Cologne churches. In “Crucifixion with the Giver and Sts. Lawrence in one of the windows of the choir of the church of sv. George we see in rough outline a rough, but expressive style of the XV century. The windows of the side walls of the church of St. Maria im Capitoli and of the left side nave of the church of Sts. Mary in Liskirchen represent the transition from the XV to the XVI century, but it is impossible to bring them into contact with certain painters with oil paints. The crucifixion of one of the windows of the Gardenratov chapel in the church of St. Maria im Capitoli seems to be "at least related" (Sheybler) to the master of the "life of the Virgin Mary" master, with whom we will get acquainted, and 5 luxurious windows with figures of the north side nave Cologne Cathedral, whose bodies in gray monochrome, blue background and rich colors of clothes, merging into one, give the pearl shine, rightfully attributed to the master of the "Holy Kind", continued to work until the XVI century. In the same way, the later windows of the Cathedral in Xanten glow with a delicate pearly luster. The oldest of them arose in 1483-1492.

Miniature painting, on the contrary, no matter how zealously it was practiced in Germany in the 15th century, did not produce in the Rhineland such works that could compete with modern French and Dutch illuminated manuscripts. More finely executed works, such as the Upper Rhine Gottfried Strasbourg, in the National Library in Brussels, the Middle Reinsky servant of the Frankfurt city library, and the Lower Rhen prayer book of the mid-15th century, in the Darmstadt library, are only exceptions that prove the rule. The flourishing Constanta school of miniaturists, as the "Chronicle of the Cathedral of Konstanz" by Ulrich von Richental in the Rozgarten Museum shows, was content with producing a purely craft character; The Alsatian bookshop of Dibolt Lauber in Hagenau, studied by Kautsham, lagged far behind its time. Even the "World Chronicle" by Hans Schilling (1459), in the city library in Colmar, has no artistic value, but is interesting for the history of art, as it reflects the sudden transition from the ancient Rothic Gothic style to the realistic Dutch.

Fig. 370. Stained glass windows in the choir of the church in Valburg. By brook

These shortcomings of miniature painting were replenished in abundance by typography invented around the middle of the century in German Middle Rhine in the last quarter of the century, as it took care of the printed pictures of the book, and next to the great wood engraving, which Muter studied, there appeared the art of engraving individual art sheets and series. It was along the Rhine that the copper blossom engraving began for the first time. The artists who were engaged in it, for the most part were well-known oil painters. Art in the Rhineland, as in the rest of Germany, mainly develops in easel painting and engraving on copper.

Upper Rhine in the first half of the XV century. repeatedly was a place where prominent people of that time were going. The congresses in Konstanz (1414–1418) and in Basel (1431–1440) made these cities the centers of European intellectual life for some time. This movement benefited the painting of these areas. Of the major revolution that took place in the art of the Netherlands and Italy, here, of course, they not only spoke, but also saw it with their own eyes; it was clearly affected by the proximity of Burgundy and its main city, Dijon, with its art gone forward. The Swabian masters were in close connection with the artistic movement that was planned in Konstanz and Basel, in the study of which Daniel Burkgardt, Byersdorfer, Rehber, Shmarsov and Degio took part. For our part, not excluding completely Burgundian and Italian influences, we insist on independence, especially of the Swabian-Upper Rhine development. Immediate points of contact with well-known craftsmen are not always needed to give rise to parallel directions. The oldest Swabian-Verkhnereinsky master, whose authentic altarpiece we possess, is Lukas Moser from Weil der Stadt. His altar is St. Magdalene in the cathedral in Tiffenbronn is marked 1431. The main picture in tympanum depicts the pouring of Magdalene of the world onto the Savior's feet, and the three main pictures below show the saint's crossing by sea to Marseille (fig. 371), rest with companions in a foreign land and her last communion Cathedral E. of the city. On the inner sides of the wings are Lazarus and Martha, still conceived like statues, on a gold background. The three main paintings, in spite of the round golden crowns of saints and still quite Gothic types, resolutely strive for an accurate transfer of space, which in the painting moves across the sea with its surface, worn out by small waves and reflecting the light of the sky, rises to the landscape that has so far only in the Dutch-Burgundian miniatures (see Fig. 323).

Fig. 371. Lucas Moser. Moving by sea over. Magdalene in Marseille. Fragment of the altar in the Cathedral of Tiefenbronn

The Gents altar of the brothers Van Eyck did not, in any case, precede these paintings. They stand on such a stage in the development of painting, which develops a space that was already almost universally achieved around 1431, and we see this development in their high-German appearance on them. The art of Konrad Vits (Sapiens) from Rottweil, mentioned in 1434–1447. in Basel and Geneva, represents the further development of the artistic direction of Moser. From the altar, made by him around 1434 for Basel, fragments in the local museum are preserved. His main work was made in 1444, four oblong paintings from the doors of the altar are in the Geneva Museum of Antiquities. The paintings on the inner sides of the wings, decorated with a gold brocade background, despite the fact that the building and the figures are written realistically, depict the Adoration of the Magi and the reverent prayer of the donor to the Madonna. Pictures on the outer sides, furnished with a real landscape, depict fishing by the Apostle Peter and his release from prison. The fishing has been moved to the shore of Lake Geneva, the opposite mountainous shore of which is conveyed very naturally. A new, strong and yet not borrowed from van Eyck sense of nature is noticeable in these softly painted flowery paintings. Strong falling shadows, which the figures cast on the walls of buildings, these paintings are close to painting with free light. This direction is even more pronounced in the big picture on the tree, in the Strasbourg Museum, which depicts St. Catherine and sv. The Magdalen in the foreground of a room similar to a cloister (Fig. 372). Their glittering clothes are spread across the floor, a wonderful view of the depth of the gallery, through the open door of which you can see part of the street. The confidence with which the artist possesses the perspective and the falling shadows competes with the calm firmness of the letter. Everything here is only vaguely reminiscent of modern Dutch. Already large golden halos, preserved by Vic, indicate a different origin. Burgundian "Annunciation" in the church of St. Magdalen in E, resembling this picture, gives the impression of a weaker and more independent work. Konrad Vits, moving from the principles of Gothic to the art of the Renaissance, was a Upper Rhine master pioneer who developed without relying, however, on any particular Dutch or Burgundian artist.

Rice 372. Conrad Vits. St. Catherine and St. Magdalene. Painting of the Strasbourg Museum. Photos of Brookman

Together with Daniel Burkgardt we can call his follower "the Basel master of 1445." He owns an interesting painting in the Donaueschingen gallery, depicting two hermits, Anthony and Paul, with a gold background instead of the sky. Justus d'Allamya from Ravensburg (near Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance) painted a fresco in Santa-Maria di Castello in Genoa, depicting the Annunciation. Despite its somewhat archaic types, it attracts with its truthfulness in the transfer of space and the abundance of light.

At the end of the XV century. in the new movement, which constituted the transition to the sixteenth century, Basel took an active part, to whom Schwabia gave an impetus, and soon Franconia. Hans Fries of Freiburg, in Switzerland, was born around 1465, in 1480–1518. mentioned in Basel, Freiburg and Bern. He borrowed his art, apparently, from Augsburg. His religious paintings are not subtle work, but they have a freshness. Renaissance buildings are found in them only after 1510. His paintings can be found, for example, in the German Museum of Nuremberg, in the museum in Basel and in Freiburg in Switzerland.

Fig. 373. Tref's dame. Engraving on copper "master playing cards." From the original

Basel, a university city since 1460, was famous for producing printed works that were luxuriously decorated with woodcuts. The development of the Basel book illustration, from simple contour, designed for coloring woodcuts - “Mirrors of human repositories” (“Spiegel der menschlichen Behaeltnisse”, 1476, ed. Bernhard Richel) - to the picturesquely executed works of Sebastian Brant, appeared at the end of the century from John Bergmann, studied Weisbach extensively. Dürer, who lived during his first journey to Basel, apparently worked for Bergmann, followed by Holbein.

The Upper Rhine took the main part in the development of an engraving on copper to thin multilateral and beautiful art in the first half of the 15th century. On the assumption that the oldest known copper-playing engraver, the master of playing cards, who, according to available instructions, had already been in 1446, was of the Upper Rhine origin, the best experts Lers and Geisberg stopped after some hesitation. Indeed, the current state of our knowledge of the Upper Rhine school of painting and its relationship to Burgundy is confirmed by the fact that the “master of playing cards” belongs to it. In any case, in contrast to many so-called "masters", he is a true master. He owns engraving with power and grace, although he does not yet apply cross-strokes; In his simple language of form, he puts a subtly felt reality. In addition to 65 playing cards, about 40 pages of his work are preserved: the graceful images of Madonn, the magnificent “St. George ”and deep in mood“ Taking Christ into custody. ” The manner in which he depicts Alpine violets, birds, etc., distinguished in his playing cards (Fig. 373) is naturally and at the same time stylishly reworked, has, as Lers rightly noted, something in common with charm original japanese art.

Fig. 374. St. Sebastian. Engraving from copper "master ES". From the original

The “master of playing cards” was then brought up by the “master of ES”, also called the “master of 1466”, whose style Friedrich Fries had already traced in Alsatian frescoes, stained glass and easel paintings, when Max Geisberg, confirming Lers’s earlier assumptions, indicated that he really was an Alsatian and even probably lived in Strasbourg and belonged to the family Reybeyzen. Lerst attributed to him about 400 pages of a religious nature. The ugly realistic type of his characters is easily recognizable by his full cheeks, high forehead, small mouth, and especially his long cropped nose at the end. With his technique “master ES”, as Lippmann said, “for the first time indicated the path by which engraving on copper could achieve full artistic expression”. He has already fully understood the intersecting hatching, at least in his later works. His playing cards, a series of apostles, a fantastic curly alphabet are famous; there are many of his biblical scenes from Genesis to the Revelation of John, many sheets from the lives of the saints, among which are interesting the work “St. Sebastian "(Fig. 374) and the image of Our Lady, the most famous is the large" Madonna in Einsiedeln "(1466).

The Alsatian artist Caspar Isenmann in 1462 pledged to write for the church of St.. Martina in Colmar altar, a few boards which are dated 1465, are in the museum of this city. The image of the Passion of the Lord, painted with oil paints and gold leaf, reveals some similarities with the works of Rogier van der Weyden and other Dutch artists, but with careful writing and a good understanding of the form, there is a well-known radical High German rudeness that makes caricatures of the enemies of the Savior.

The fame of the ES Master and Caspar Isenmann, however, quickly faded before a rising star Martin Schongauer. His father, a native of Augsburg, was a goldsmith and ratman in Colmar. Here Martin was born around 1445 or earlier; here it is mentioned as early as 1488, but in 1489 he moved to Brayzakh, where he died in 1491. A. Waltz published a bibliography relating to works on Schongauer on behalf of the Schmarhauer Colmar Society. For us, research of Scheubler, Seidlitz, Lers, Lübcke, Daniel Burkgardt, M. Bach, Amand-Durand and Duplessis mainly matter. Coming out of the jewelry workshop, Martin Schongauer took up copper engraving. There are 115 engravings of his work, marked with the artist's monogram; in their technique, it is from the previously prevailing custom of hatching with simple features that it reaches the use of a real cross-stroke. In his hands, an engraving on copper for the first time produced such pictorial effects that, until then, it had never been suspected of. Engravings with Shongauer's ornaments use the Late-Gothic language of forms exclusively; all his works are inherent in that spirit of rigor, which is a feature of northern art of the 15th century, but he almost overcame the rudeness of most of his fellow countrymen today. The language of its forms is clear, delicate and distinct, as in the modern Dutch people. It is also possible that in his youth he traveled to the Netherlands, but that he was a pupil of Rogier van der Weyden in Brussels seems unlikely. Even if his types and motifs of compositions remind here and there of this master, his High German imagination, which is already evident in the nervous mobility of long thin fingers and in the flexible members of lean figures, appears everywhere. With time, the realistic sharpness of his earlier works gives way to a clearer, personally experienced sense of beauty. It is surprising that from the Dutch tradition of that time he often returns to German custom even in his later works: the Savior and the Mother of God portrayed without haloes, and the Virgin Mary painted with a halo in the form of a disk. Schongauer surpassed all his northern contemporaries with a wealth of imagination. Only a few could, as well as he could, convey a state of mind. A new look at sacred events, spreading through its engravings, spread everywhere and subdued the minds of several generations of artists. The manner in which he portrayed the temptation of St. Anthony fantastically accumulated hellish fiends, came into use by his contemporaries. The way in which he, in his “Big Carrying the Cross” sheet, conveyed this amazing scene with its huge procession, became the property of the centuries. In the work “Peasants Going to the Market,” he stunningly connected the plot with a landscape depicting a village with ruins. The great series of the Passion of the Lord shows the inexhaustible inventiveness and creative power of the master in full splendor: the butchers of the Flagellation really attacked the Savior with frenzy (fig. 375). In the work Madonna with a Parrot, the Mother of God is represented without a halo, and in Madonna in the Courtyard (fig. 376), with a smooth corolla. In the last engraving, the refinement of feeling is already visible, with which, at his mature age, he was able to coordinate the lines of the landscape background with the lines of the main figures.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)