1. Features of the period sculpture

Sculpture technique in Italy of the XVII century becomes more closely associated with architecture and painting. The realism of the performance of statues and the transmission of movements in this era have reached new heights, while the image of figures at rest was not widely spread.

The turn from the alien to the unthinking application of traditional formulas to the new observation of nature and a more serious understanding of the essence of the old great masters was first of all accomplished in Italian painting, the new breeding ground of which was the so-called Carracci Academy in Bologna, and not in sculpture, which was still at the end of the 16th century possessed a contemporary of Carracci, such a large representative of an older direction, like Giovanni da Bologna. Further, in painting, as we shall see, more clearly than in sculpture, a new naturalistic trend appeared along with a new academic one. But in sculpturing both directions were more decisive than in painting, they were picked up, connected and carried away by the great flow of Baroque, the powerful flow of which so evenly drew architecture, sculpture, painting and ornamental art so that none of them decided to perform without communication with others. .

Sculpture, precisely without its connection with the architectural space, was no longer in the XVII century. The reservoirs in the squares, tombs and altars in the churches were in unequal connection with the surrounding architectonics, while at the same time, the boundaries between the tasks of sculpture and painting became more and more blurred. What the painting has achieved in expressing the internal and external power of feeling, flowing clothes, agitating outlines, even strong colorful and light effects — all this has now been considered by free circular plastic as its property; and the relief, which was already performed by Ghiberti, according to the rules of painting, finally turned into a kind of frozen painting. The front figures tend not only to complete plastic roundness, but also go beyond the frames, following the example of the later works of Donatello. Clouds and curtains play in the sculptural works almost the same role as in painting, and whole altar niches are decorated with sculptural images and appear as plastic pictures.

The concept of plastic peace was completely alien to the Italian sculpture of this century. The calmly standing figures were not tolerant. Even allegorical figures were placed in a lively, often dramatic relationship to each other; and not only in poses, often poorly matched with the arrangement of clothes, but also in the game of people they tried to express life and passion. But that healthy naturalism of the language of forms, which forms the basis of such excitement, although it was everywhere the aim of aspirations, however, in most cases, involuntarily turned into a more or less high-spirited way of expressing a new style. And now the art of sculpture, the essence of which is based on direct observation, remained true to the artlessness of nature the longest.

For all that, our time does not at all relate to the characteristic creations of the sculpture of this style as negatively as Jacob Burckhardt and Wilhelm Lübke treated them. A great artistic person ennobles in our eyes the style of every nation and every epoch, and Italian sculptor found now in Lorenzo Bernini a powerful artistic personality, so powerfully and convincingly embodied the style of the era, as if he had come out of her deepest revelations; and as Giovanni da Bologna, mentioned earlier, the most significant of Bernini’s closest predecessors, was already standing with one foot on the way to baroque, then in Italian sculpture the transition from the mannerism of the second half of XVI to the style of the XVII century was made more uniformly than in painting. the development of which was delayed by Carracci.

Distinguished names

Of the three masters, followers of Giambologna, who created the reliefs of the cathedral doors in Pisa, Pietro Tacca (circa 1580–1640) especially served as a transition of Tuscan art in the 17th century. On the base of the copper equestrian statue of Ferdinand I in Livorno, the work of Bandinelli's pupil Giovanni Bandini (circa 1540–1600), Tacca performed the very vital bronze slaves of the Moors; for Madrid, he performed the famous equestrian monument of Philip IV, with a horse rearing up that served as a model for later sculptors; the busts of Ferdinand I in Bargello in Florence and Giambologna in the Louvre are also works of his hands.

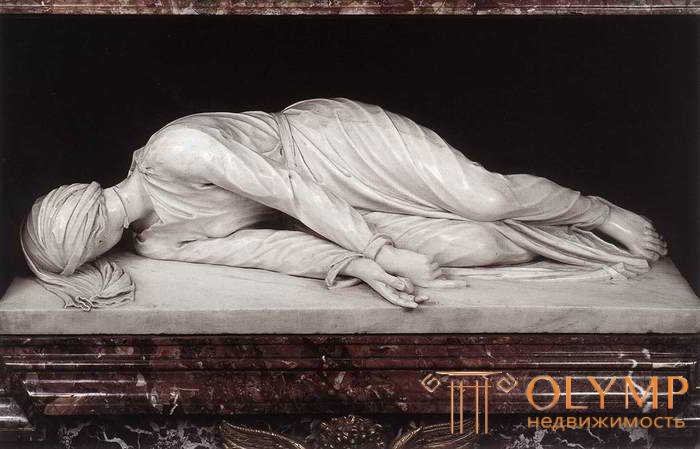

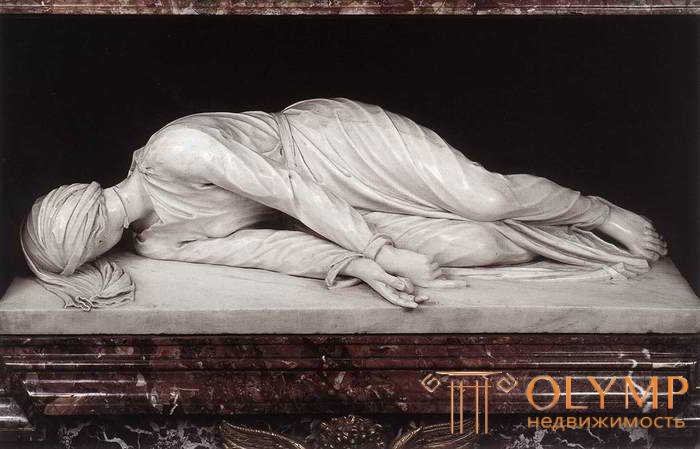

Fig. 103. Stefano Madern. Sculpture of lying St. Cecilia in Santa Cecilia in Rome.

2. Creativity Lorenzo Bernini

Lorenzo Bernini, who is also called the "Michelangelo XVII century", is recognized as the most famous Italian sculptor of the era. Most of his works he performed in Rome, including monuments to the three Roman popes, during whose reign he worked. In the works of Bernini can be traced several distinct stages, each of which he adhered to different styles.

Finally, Lorenzo Bernini himself appeared, "XVII century Michelangelo" (1598 to 1680). The son of a dry Florentine sculptor Pietro Bernini, who moved to Naples in 1584, and in 1605–1607. former president of the Academy of sv. Luke in Rome, he was born in Naples, but developed into an artist only in Rome, as a pupil of his father. His first biographer was Balducci, his second son, Domenico Bernini. In Italy, Frasketti devoted a lot of work to him recently, in Germany Pollak is a good study, Chudi is a convincing article. We have already met with his architectural works. As a sculptor, he was the idol of the century. Early reaching technical mastery, in which he joined the late antiques with their play of light and shadow, achieved, on the one hand, by rough incompleteness, on the other, by excessive incarnation, gifted by nature with great power of sensual contemplation, and in the portrait area it was distinguished by the most careful observation nature, however, always ready to rape nature in favor of inspirational decorative effects, he managed to breathe into the style of his time so much youthful fire, so much amazing power and vitality that he found a new excuse, even the appearance of inner truth and authenticity, at least in the area of external manifestations. Only the abundance of anxious lines of his senile style, with intentionally dislocated body forms, theatrical pathos of sign language and impossibly swollen, flowing clothes, became intolerable. In any case, “I want” and “I can” in Bernini merge so much as in rare artists.

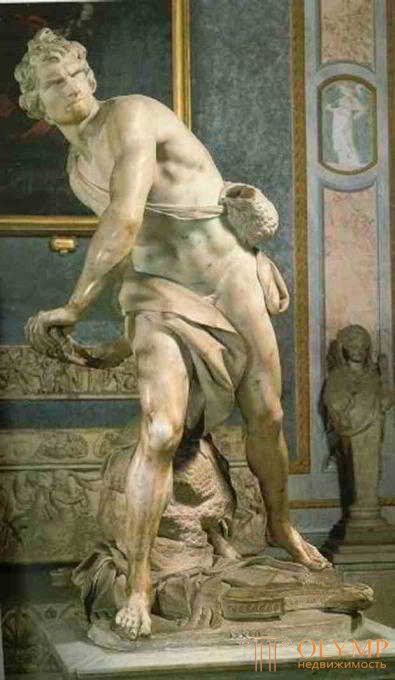

Of his juvenile works, which appeared before the death of Gregory XV (1623), the Aeneas marble group with Anchises on his shoulders in the Villa Borghese, attributed to his father Pietro, and the abduction of Proserpina Pluton in the Piombino Palace in Rome still resemble the style of Giovanni Bologna. But how artistically independent, how expressive and meaningful are his early busts on the monuments of Bishop Santoni in Santa Praséde, Giacomo Montoya in Santa Maria di Monferrato and Paul V in Villa Borghese in Rome! How deeply and truly felt are the marble busts of the blessed and condemned souls in the Spanish Embassy in Rome! How much power and truth of life is in the movement of the body and the expression of his prankster David in the Villa Borghese, in comparison with which David Michelangelo breathes only a hidden life! What a thrill of beauty and what internal animation in his famous Apollo and Daphne group (ibid), trying to bring visualization to light, depicting the transformation of a pursued nymph into a laurel tree! Everywhere refined marble finishes tend to surpass nature with their delicate body shapes.

Fig. 104. David at the Villa Borghese in Rome by Lorenzo Bernini.

Under Urban VIII (1623–1644), his special friend and patron, Bernini experienced a flourishing of brave strength striking over the edge. His portrait busts reach a rare height in their physical and mental truth. The marble bust of his former beloved Constanza Buonarelli in the National Museum in Florence breathes with strong sensuality and spiritual dryness. As a living person, Cardinal Scipio Borghese is before us in both of his marble busts of the National Gallery in Venice. The majestic and noble impression is made by the bust of Bernini by Charles I in Windsor, made from drawings by van Dyck. Outwardly and internally animated is the large marble seated figure of Urbana VIII with his blessing right hand in the Palace of the Conservatives in Rome. But the tombstone of Urban VIII in the church of Sts. Petra Here is almost the same, but a bronze, sedentary statue crowns the sarcophagus, in the midst of which writhes the often deprecated, half-closed, gilded winged skeleton, writing on the blackboard the name of the deceased. Leaning against the sarcophagus and the basement in lively groups, surrounded by putti, on the left, Mercy with children, on the right Justice with a sword. For many decades, no other was created, so stately and with all the liveliness of a calm and integral gravestone monument.

To the best works of this master belong to his reservoirs, many contributed to the development of a new physiognomy of the city of Rome in the XVII century. Under Urban VIII, the remarkable Bernini reservoir in the form of the warship “La Barcaccia” on the Spanish Square and its magnificent reservoir with tritons in the Barberini Square, which became a model, were created, among others.

Under Innocent X (1644–1655), Bernini temporarily fell out of favor. His works of this time reveal an increase in the desire for a pathetic one and a desire for refined skill. The extreme expression of this direction is “Ecstasy of sv. Teresa "in Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. Leaning back in golden rays, clothed in clothing, falling in broken folds, the saint in ecstasy awaits the heavenly bridegroom, the approach of which is announced by the angel standing in front of her, looking like a cupid, directing a golden arrow into her. The group gives the impression of a Christian reworking of the Danae motif. The most famous fountains of Bernini of this time adorn the Piazza Navona in Rome. A large, crowned by obelisk circus Maxentius, the average body of water was adorned by his students in his drawings with four realistic, among the landscape, conceived figures of the rivers Ganges, Nile, Danube and Laplat. The pond with tritons on the north side of this square represents only a remake of the old reservoir that still existed here.

Under Alexander VII (1655–1667), Bernini began to age. Still relatively calm and noble is his famous recumbent statue of Sts. Albertons in San Francesco a Ripa in Rome. The soulless statues of the prophets in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, the arrogant bust of Louis XIV in the Versailles castle, the truly monstrous bronze cover of the chair of St. Peter last chapel of the church of sv. Peter, the famous, executed pupils posing angels on the bridge of St. Angela (two copies of his own work were set up in Sant'Andrea della Fratte), and finally the tombstone of Alexander VII in the cathedral of Sts. Peter in Rome, on which the skeleton lifts a heavy brown jasper curtain over the door, on the upper jamb of which stands a sarcophagus with a kneeling marble figure of the pope. Christian Virtues with bitter tears wriggle under and over the canopy. And yet this far-fetched, exquisite work reveals the unity of mood and true ardor in comparison with the works of most of the followers of this master.

3. Opponents and followers of Bernini

Bernini's work had a strong influence not only on his students, but also on his contemporaries. At the end of the century, some French sculptors worked in his style, including in Rome. There was also a large Italian school, antagonistic Bernini.

Even older masters, such as Mocha and Duquenois, fell randomly under the influence of Bernini. However, from the set of his students and free followers, none acquired independent meaning. Giuliano Finelli from Carrara (1602-1657), about whom Passeri already speaks in detail, helped Bernini in his early works, such as Apollo and Daphne, but already independently performed the excellent portrait bust of Maria Barberini in the Bologna Certose. Andrea Boldi (1605-1566) worked for Bernini in various places of the Cathedral of Sts. Peter, and independently executed for the fourth niche of the dome columns a statue in full growth of St. Helena with a cross. Francesco Baratta (died in 1666) not only worked in the Cathedral of Sts. Peter, under the leadership of Bernini, but also performed in his sketch relief, sustained in a picturesque style altar image of the Assumption of St.. Francis in San Pietro in Montorio in Rome. Of the four great rivers of the main fountain on Piazza Navona, he performed Laplatu, Antonio Raggi (1614–1686) - Danube, Claudio Porissimo - Ganges, Giacomo Anthony Fanchelli (1619–1676), one of Bernini’s faithful employees in the cathedral of St. Petra, Nil. Giovanni Antonio Marie, an employee of Beronini in Santa Maria del Popolo and in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, performed excellent tritons in the middle of the northern reservoir of Piazza Navona. Ercole Ferrata (1610–1686), Comrade Marie for work in the churches mentioned, graduated under the direction of Bernini, the famous marble elephant under the obelisk of the Piazza della Minerva.

At the end of the century, French sculptors, developing under the influence of Bernini or his works, found a friendly welcome and a versatile field of activity in Rome: they were headed by Pierre Legros the Younger (1656 to 1719), who sang the very richly painted statue of the dying Stanislav Kostka in Sant'Andrea during the Quirinale, and ecstatic relief of St. Ludwig in Sant'Ignazio in Rome.

Fig. 105. Leo I and Attila. Relief of Alessandro Algardi in the Cathedral of St. Peter in Rome.

Of his students, Domenico Guidi (1628–1701), his chief collaborator at the Leo XI monument, later moved to Bernini, for whom he performed one of the angels on the San Angelo Bridge. But from the followers of Bernini, Ercole Ferrata performed the allegorical figure of the Majesty on the monument to Algardi.

The pupil of Ercole Ferrata, Giovanni Battista Foggini (1652, died later 1737), who, with his brothers, performed the dull tombstone of Galileo in Santa Croce in Florence, transferred Bernini’s style to this city. His main work here is considered to be the gravestone of Andrea Corsini decorated with three large marble reliefs in the Church of Carmine.

The Milan Cathedral, the Pavia Certosa and the holy mountain Varallo were also richly decorated with new sculptures in the 17th century. In Naples, the birthplace of Bernini, his style was brought by such a major artist as Andrea Boldi, who founded a school here. In Palermo, Giacomo Serpotta (1656–1732), whose famous bronze equestrian statue of Charles II in Messina was destroyed in 1848, filled many churches with charming, strikingly pure forms for that time, with plaster figural ornaments, thoroughly researched by Marchery. If in earlier works everywhere it is possible to trace a gradual transition to the direction of Bernini, here there is already a transition from the high baroque of the XVII century to the rococo of the XVIII century.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)