1. Overview of the features of Italian period painting

Italian painting in the period under review begins to lose its exceptional position in Europe as the schools of Spain and the Netherlands develop. Nevertheless, many of its currents, especially architectural painting, were advanced for that era.

In the 17th century, Italian painting was to cede the primacy that it enjoyed in the 16th century to its Spanish and Dutch sisters. It was in Italy that the painting of the 17th century was hardly conscious of its true abilities: more precisely, it was not at all conscious of the Carracci school in Bologna, which took the leading role in the eclectic-academic direction, and only partially recognized it in the naturalistic direction, headed by Caravaggio. It is remarkable that the greatest painter in the true sense of the word, now in force in Italy, was Ribera, the Spaniard. And if Carracci, whose school flourished already in 1585, with the resumption of the late style of Raphael, Michelangelo and especially the idol of the school of Correggio, resolutely began to create the baroque with its deliberately contradictory movements and inflated forms, then the further development of the baroque in the spirit They had a deterrent rather than a supportive effect to Bernini. Nevertheless, it is impossible to deny that they differed from their predecessors, mannerists who moved without independent thought, on paved tracks, with their dignity, thoroughness and the power of consciousness with which they studied, according to their own statement, the old masters and nature, so that, having taken from everywhere best, “eclectically” merge it into a new unity. That this desire too often took away the immediacy of observation and perception from them is understandable by itself. But it is also self-evident that in contrast to this direction another, realistic, striving to return to nature arose, a current without which a serious decline would have been revealed in Italy.

The history of the 17th century Italian painters was written with passionate enthusiasm by their contemporaries: Baldinucci, Balione, Baruffaldi, Bellori, Boskini, Vedriani, Malvasia, Pascoli, Passeri, Ridolfi, Skamuccia, Skanelli Soprani. Most of these writers, known for their commitment to high ideal art, from which they simultaneously demanded “forza”, “grazia” and “decoro” (that is, strength, grace and grace), declared themselves determined supporters of Carracci and their so-called Academy , opponents of "naturalezza" (naturalness) Caravaggio, the strengths of which they noted with some timid admiration. Their judgments were repeated for two hundred years. A more sober attitude towards the Carracci school, which Janiczek aptly pointed out, was already carried out by Jacob Burckhardt, and a more sympathetic assessment of Caravaggio and Ribera was conducted by FW Unger, Eisenman and others. From the point of view of modernity, Schwerber and Posse of the 17th century Italians appreciated, and Titse tried to critically investigate and distribute their paintings according to style.

Architectural painting

None of the European countries in the seventeenth century decorated such huge areas with paintings as in Italy. The fresco painting of churches and palaces occupied mainly the upper parts of the walls (friezes), ceilings and domes. The powerful altarpie inspired by the altarpieces filled the gigantic altars of the new churches. All this painting, designed for a long distance, is understandable in itself. Smaller religious and secular paintings lay on the walls of residential palaces. New, inspired by nature and life, images, as well as pictures of national life, initially performed in life-size, and soon became small-figured and abundant figures, enjoyed success only within the naturalistic direction, while the landscape, which had independent significance in Italy of the 16th century only as decorative wall painting, has it now been conquered by easel painting, without achieving the intimate realism of northern landscape painters. Specialists artists who wrote the fruits and flowers, are first found as isolated phenomena. The portraits wrote "eclecticism" and "naturalists", and the portrait painting of the XVI century not only did not move forward, but even failed to reach a certain height of it. The prevalence of everywhere preserved religious and mythological painting.

We first trace the directions of the academically-eclectic, then the naturalistic and, finally, the new directions of the second half of the XVII century, in which, along with the late Baroque in the sense of Bernini, here and there the already great lightness and charm of rococo is manifested.

Ludovico Carracci and his family

Ludovico Carracci (1555–1619), the founder and leader of the eclectic-academic school of Bologna, a student of Prospero Fontana, was the uncle of his cousins Agostino (1558–1602) and Annibale (1560–1609) Carracci, who spread his direction in Rome and throughout Italy. From their early collaborations in Bologna, a frieze with the history of Romulus and Remus (circa 1589) is issued at the Palazzo Magnani. Ludoviko is still half a manist here, Agostino is the most fresh in the landscape, Annibale is also gratifyingly a bright copycat of Correggio. Around 1593, their magnificent paintings of the shades and fireplaces of the Palazzo Sampieri, representing the exploits of Hercules with baroque motifs, appeared. But the main joint work of Carracci and their older students was the famous frescoes of the large gallery of the Palazzo Farnese in Rome (1595–1604). Ludoviko, if he took part, it was only in the sketches, but not in the performance; Agostino knowingly wrote only both medium-sized paintings on the friezes of the longitudinal walls; the soul of all was Annibale, who owns the lion's part in performance. A concave belt, like a frieze, dissected only by atlantes in the form of germs and bronze shields, is separated from the mirror of the ceiling of the ceiling going through the light arch. Gigantic youths inspired by Michelangelo's canopy, are located in front of the Atlanteans; masks, shells and garlands of fruits fill the corners. Of the thirteen main paintings representing the love adventures of the Greek gods, three are on the ceiling, the others are on a concave frieze, and the four middle ones imitate the style of hanging easel paintings. In the center of the mirror of the plafond, a large pompous force of the picture of Annibale with the triumphal procession of Bacchus and his magnificent suite is striking, and the side panels glorify “Mercury and Paris”, “Pan and Selena”. Both Agostino paintings on a concave frieze, depicting “Aurora and Kefal” and “The power of love over the inhabitants of the sea” (apparently Galatea), are drier, but nicer in drawing and colder in colors than those of Annibale, which develops here in shapes and colors its powerful roman style. Four paintings of Annibale on the longitudinal sides, representing Zeus with Hera, Anchise with Venus, Diana with Endymion, and Hercules with Omphaloy, differ in their greatest force of forms. Separate images on the lower four walls are made mostly by Domenichino based on sketches by Annibal. As a seamless decoration, the ceiling of the Farnese Gallery remains the greatest work of the early Baroque, the creation of inexhaustible luxury of forms and colors, at the sunset of this century once again uniting all the forces of the XVI century.

Ludovico Carracci, who was great as a teacher and painting technician (he invented a red terdesen background for oil paintings), worked in Bologna and, as is quite obvious, left the Mannerist school, but then consciously followed Correggio, whose charm turned into pathetic power. In the cathedral of Piacenza are the most recent frescoes depicting angelic choirs (1605). Of the numerous altar paintings, the Baptist Pinakothek’s baptismal sermon and the heavy “Vision of Francis” were presumed to be old, and the Transfiguration of Christ in Bologna’s Pinakothek and The Position in the Tomb of Mary of the Parma Gallery are already in the new century. Convinced that art can be learned, Ludovik tirelessly sought to perfection.

Agostino - the most versatile, the most learned and independent of the three Carracci. He is primarily an engraver. He borrowed his juicy, intricate stroke from Roman Cornelius Court, a native of the Netherlands (died in 1578). The most famous prints from the paintings belong to his large Crucifix, made by Tintoretto. His independent engravings and etchings, advanced in this field for Italy, cover all sorts of topics.

From the frescoes of Agostino, mythological love scenes on the ceiling of the Palazzo Dzhardino (military school) in Parma are notable for their cheerful, fresh beauty. His famous altar images, such as: the expressive Communion of St.. Jerome and the Assumption of Our Lady of Bologna Pinakothek with the movement of figures in a new spirit felt and arranged almost independently. But his female portrait of the Berlin Gallery and the river and mountain landscapes in Palazzo Pitti are already proving him to be a close, albeit biased attitude to nature.

Annibale Carracci, apparently, was naturally endowed with a naturalistic twist that appears in his “Lute Player” of the Dresden Gallery. However, he soon submitted to Cordugi's understanding of the painting of his teacher Ludoviko. His early large altar images of 1587 and 1588. connect the types of Correggio with sudden movements and gross greatness of Ludovico. When Annibale found himself, his sense of form and color grew stronger, but did not become independent. His colossally huge image of St. Roch in Dresden (1595) is a strong popular genre with crude types, but without the prevailing unity of action. At the same time, Corrigue's sense of light and color is still manifested in his Christ in the clouds in Pitti Palace, and only Maria's Ascension in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome shows him standing on the new paths of his inborn Roman talent. Christ, who is Peter, in London, shows that Annibale was able to transmit inner excitement only through external movements. In the mythological easel paintings, of which, by the way, Titz ascribes to him the famous Venus Domenichino in Chantilly, and the full “Learning to Music” mood in London - Albano, he seeks to harmoniously merge the sense of nature with a sense of style. He was also the first Italian to write biblical or mythological landscapes with oil paints on a shelf. True, his series of six landscapes in Palazzo Doria in Rome, where "Rest during Flight" and "Position in the Coffin" were written by him personally, judging by the composition, served only as an ornament to the fields of the arch; some of its external decorative features also differ in its individual landscapes in London, Berlin and Paris, of which the early Louvre painting, which is magnificent in its colors, shows that Annibale also studied from the Venetians. His stately scattered mountain ranges, groups of trees and water surfaces influenced in turn the northern landscape painters who worked in Rome.

2. Followers of the Carracci School

The work of the Carracci family had a profound impact on Italian art. The most outstanding continuers of their work in the 17th century were five artists: Guido Reni, Francesco Albano, Domenico Tsampieri, Francesco Barbieri and Giovanni Lanfranco.

The five masters of the Carracci school, with complete unity of goals representing completely different artistic personalities, became the head of further development. Of these, Guido Reni, Francesco Albano and Domenico Tsampieri, nicknamed Domenichino, were born in Bologna, Francesco Barbieri, nicknamed Gverchino, was from a neighboring Cento, and Giovanni Lanfranco from Parma.

Guido Reni (1575–1642), was only a short time student of Carracci, but became a typical representative of the academic direction of Bologna. Gifted and prolific, he, however, looked at nature through the eyes of Antique and Raphael. He did not write landscapes and, except for a few portraits with an etching, he did not give others. Even the perfect portrait of the imaginary Beatrice Chenchi in the Palazzo Barberini in Rome in recent years is not recognized by his work.

In Rome, where we see him again in 1605, he temporarily fell under the influence of Caravaggio, as indicated by his Crucifixion of Peter in the Vatican, performed in black shadows, and the full force of the fresco depicting St. Andrew in San Gregorio Magno. The colorful period of his life in bloom was followed by the silvery tone of his old age, which in the end degenerated into a dull sluggishness of colors. In full, bright splendor of colors shines its famous “Aurora”, finished in 1609, the ceiling painting of one of the halls on the garden side of the Palazzo Rospilosi in Rome. The mountains around the quadriga of the young man Helios are dancing with a lovely round dance, and Eros and Eos are flying ahead. With all the commonness of the language of forms, the picture breathes a cheerful sense of beauty and poetry of flowery colors. One of the most vital, though unseasoned, works of Guido Reni, “The Beating of the Bethlehem Babies” of the Bologna Pinakothek, glows with a golden tone, while the silver-radiant Assumption of Mary in Sant Ambrogio in Genoa is among the best altar images. His head is famous for the crown of thorns in Vienna, London and Dresden, although it is they who show that the strong expression of the emotional feeling that he sought was too often weary and weak. As a little heroic in his idea of the Old Testament and Greek heroes, show him Samson and Apollo, ripping off the skin from Marcia, in the Bologna and Munich Pinakothek. Sleeping Venus in Dresden, however, is distinguished not only by the impotence of the colors of his late manners, but also by the ideal language of the forms and the transparent letter that has always been characteristic of him. Guido died the generally accepted head of the Bologna school.

Francesco Albani (1578–1660) was akin to Reni, but a lesser talent with a strong penchant for the landscape. Of the youthful works, the lively Christmas of Mary in the Palace of the Conservatives in Rome already gives one of those lovely children's dances that have become his specialty. Mythological ceiling murals of Albani in the Palazzo Verospi (Torlonia), flowery in color, suffer from a dry and meaningless drawing of individual figures, typical of Albani's paintings with large figures. In his small easel paintings, often painted in Dutch patterns on copper boards, these shortcomings are not so noticeable. The folded foliage of the trees in their cheerful landscapes again resembles Dutch patterns. Dancing putti, his independent wealth, give them a pleasant revival. Religious paintings of this kind can be seen in the Louvre, Dresden, St. Petersburg. Mythological paintings of putti or amurchikov are famous, such as The Four Elements in Turin and in the Borghese Gallery, The Abduction of Proserpina in Brera and Dresden. It was Albani who provided this “Alexandrian” art, in which rococo motifs, a happy future, lurk.

Giovanni Lanfranco (1580–1647) enjoyed the high esteem of his contemporaries. Already in Parma, where he grew up, he was fascinated by Correggio. According to Titsa, Annibale Carracci’s “Tombstone” penetrated by the light in the Borghese Gallery was executed by him. Adjoining to Correggio, he wrote his dome compositions with the right eye of the viewer below and applied harsh lighting effects in contrast to ceiling paintings by Carracci and Reni. However, the composition dispersed in a new spirit and the wide manner of writing of this master foreshadow a high baroque. His innovations were often taken for creative action. The main work of Lanfranco in Rome is the Assumption of Mary in the dome of Sant'Andrea della Valle (1621–1625). In Naples (1631–1641), his main works are the frescoes of the choir in San Martino, the domed frescoes in the sacristy of the cathedral. His cleverly scribbled easel paintings with oil paints "The Remorse of Peter" in Dresden, "The Death of Paul and Peter" in the Louvre, "The Liberation of Peter" in Palazzo Colonna in Rome show in many respects a connection with naturalists, but generally produce only an external impression.

Deeper, more conscientious and more intimate than Lanfranco, Albano and Reni, Domenichino (1581–1641) worked, who was able to combine his characteristic sense of nature with a purer sense of beauty. To the early period of his activity Titsa attributes some of the paintings that were considered to be the works of Annibale Carracci. In the early Roman works, such as the Liberation of Peter in San Pietro in Vincoli, the frescoes of the martyrdom of Andrew in San Gregorio Magno in Rome (1608) and the Adoration of the Shepherds in Dulwich College near London, he was apparently influenced by Caravaggio. But already his frescoes from the life of St.. The Nile River with famous trumpeters in Grottaferrata (1609–1610) is replete with a fresh sense of life and style, reaching full completeness in the beautiful frescoes of Cecilia in San Luigi de Francesi in Rome. After 1621, a mature series of Domenichino frescoes appeared in Sant'Andrea della Valle with famous evangelists in the dome sails, in comparison with which the movements of the main Virtues in San Carlo ai Katinari seem more artificial.

The most famous altarpiece of Domenichino, "Communion of St. Jerome ”in the Vatican, there is only a deeper further development of the image of Agostino Caracci in Bologna. Мифологическая картина «Охота Дианы» в галерее Боргезе, самая известная, проникнута свежим, светлым настроением ландшафта, а его настоящие ландшафты в римских и английских собраниях, в Лувре и Мадриде, набросаны более уверенно, освещены ярче и написаны сильнее всего, что есть в этой школе. Знаменитым отдельным женским фигурам этого мастера, каковы «Св. Цецилия» в Лувре и «Кумская сивилла» в палаццо Боргезе, при всей их прелести, не хватает внутренней жизни, а его «Жертва Авраама» в Мадриде, сравнительно с картиной на ту же тему Андреа дель Сарто того же собрания, пользуется уже академическими позами школы Карраччи.

Fig. 106. «Кумская Сивилла» Доменикино в палаццо Боргезе в Риме.

Младший и в некоторых отношениях самый привлекательный из пяти главных мастеров академической школы Болоньи — это Гверчино из Ченто (1591–1666). Едва ли он был личным учеником Карраччи. В его ранних произведениях, каковы «Мадонна со святыми» (1616) в Брюсселе, «Распятие» (1618) моденской галереи, «Тавифа» (1618) в палаццо Питти, сильнее заметно чувство природы Караваджо с его черными тенями, прорезанными ярким светом, чем влияние Людовико, картинами которого он восхищался в своем родном городе. Резким завершением этого развития является его «Св. Вильгельм» (1620) в болонской Пинакотеке.

С 1621 г. являются великолепные плафоновые фрески Гверчино в вилла Людовизи в Риме: в верхнем этаже примечательна, свежа по краскам и линиям форм богиня славы, а в главном зале нижнего этажа смелая Аврора, с которой началось применение точки зрения снизу и в области плафонной живописи дворцов. Той же высотой живого языка форм и общей яркостью красок отличаются фрески (1626–1627) купола в соборе Пьяченцы и станковые картины, каковы «Погребение Петрониллы» во дворце Консерваторов в Риме, поясные фигуры евангелистов в Дрездене (1623), «Блудный сын» в Турине. Как широко разрабатывал он ландшафт, показывают особенно его рисунки пером. Приняв на себя в1641 г. руководство болонской школой, он счел себя обязанным идти по стопам своего предшественника Гвидо Рени. Достаточно вспомнить его «Агарь» (1657) в Брере и ряд дрезденских картин, чтобы убедиться в обобщенности eго языка форм, бессодержательности и вылощенности исполнения, в приторной пестроте красок его поздних произведений.

Fig. 107. "The Prodigal Son", a painting by Guercino in the Turin Museum.

Other representatives of the school Carracci

The rest of the Carracci Masters cannot be listed here. It should, however, point to landscape painter Giovanni Battista Viola (1576–1627), whose landscape in the Borghese Gallery adjoins the early Venetian style of Annibale’s landscapes. Agostino Tassi (circa 1566–1642), the teacher of Claude Lorrain, is already a pupil of the Roman Netherlands and is known only from half-landscaped paintings, such as the “Grottaferrata Fair” in the Corsini Palace (National Gallery) in Rome, as his frescoes in the Palazzo Lanchelotti is not available for study.

From the second generation of students of Carracci, we are primarily captivated as the founder of the school in Rome, the student of Albano Andrea Sacchi (1600–1661), the classical master, who unites in his paintings, for example, “Vision of St. Romualda "in the Vatican, the purity of body shape, widely falling clothes and a clear, imbued with light color with calm greatness and sincere sincerity.

The second generation of the Carracci school also included a pupil of Reni Guido Kanlassi, nicknamed Kanyachchi (1602-1681), who contributed to his easel paintings, such as Cleopatra in Vienna, Magdalen in Munich, a new colorful painting of the painting and a new mood of the soul; Besides the generation of Carracci’s students, Giovanni Battista Salvi, nicknamed Sassoferrato (1605–1685), wrote the Madonnas, whose conventional form language and whitish coloring, reminiscent of Renee, made him a favorite of cool academic taste.

3. Other Italian Schools

At the same time as the Carracci school, there were other schools of painting in the same direction, mainly located in Rome, Florence and other major cultural centers of Italy.

The currents of the epoch usually make their way in different places at the same time, fed by the same, often invisible sources. The movements parallel to the Carracci school arose in all the ancient Italian centers of art. All of their threads, however, came to Rome, still the artistic capital of Italy, thanks to a number of popes and cardinals who appreciated art.

In the first half of the century in Rome, along with bold innovators of both directions, the skillful, though mannered, follower of the old masters Giuseppe Cesari, Cavallere d'Arpino (about 1560–1640) came forward; known for his Roman historical paintings in the Palace of the Conservatives. However, the main center of independent artistic creativity, which was walking alongside the direction of Carracci, was Florence, where after imitation of Michelangelo, the cheerful colors of Andrea del Sarto prevailed. The motives of movement in the Baroque style are carried out here with greater feeling than in Bologna, in the transfer of sensations they say the look and the game of physiognomy. Paints are more juicy and brighter.

True, in portraiture of Florence, the Dutchman Justus Soustermans, or Suttermans (1597–1681), now became dominant. However, the Florentine decorative painting, although it came out of the Roman “grotesque”, now went its own way. The relatively simple masters of transitional time, skilled in the paintings of the vaulted spaces of the monastic courtyards, Santi di Tito (1530–1603) and Bernardo Pochetti (1542–1612), continue to live in the 17th century. They were joined by Antonio Tempesta (1555–1630), who used to paint friezes with fresco paintings with legends, hunts, battles, and trips of knights in the palaces of Rome and Florence, but also engraved on copper. Depending on Pocchetti, he later developed in Rome his blossoming, designed for massive contrasts, the high baroque style of Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669), a glorious architect and ceiling painter. If, on his famous ceiling Palazzo Barberini in Rome, architectural painting for the first time makes an impression of unity when viewed from below, then the figured part of the composition on the concave ceiling of the church of Santa Maria in Valicella in Rome is designed for complete unity of impression from below. His mythological wall and ceiling paintings in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence already hint with their sweet levity for the XVIII century.

Pupil Angelo Bronzini Alessandro Allori (1535–1607), father of Cristofano Allori (1577–1621), in the field of Florentine easel painting was the best master of the bright colorful direction of this era. Already "Judith" and "The Victim of Abraham" in Palazzo Pitti show all the originality of his confident forms and bright lighting. Santi di Tito was a student of Ludovico Cardi, nicknamed Chigoli (1559–1613), the founder of a school in the academic spirit, who is the Florentine Carracci. Starting with "St. Lawrence, his early work (1586), and ending with the late “Calling Peter” (1610), he develops an exceptionally closed composition and feeling. The influence of Fra-Bartolommeo and Andrea del Sarto with a great boost processes Jacopo Jimenti da Empoli (1558–1640), as indicated by his “St. Ivo (1611) in the Uffizi. At the head of another school, influenced by fellow practitioner Chigoli, Gregorio Pagani (1558–1605), is Matteo Rosselli (1578–1650), a master with a more faithful sense of nature and beauty, which his “David” (1621) already breathes in Palazzo Pitti, given him the opportunity to form a school. From his pupils, Giovanni Manozzi da São Giovanni (1590–1636) is issued, the frescoes of the cross of which in Onyssanti give an idea of him as a brilliant storyteller, and genre paintings, such as “The Artists Revels” in Uffizi, the Company of Hunters in Palazzo Pitti, - as an independent observer of nature and light. The pupils of Rosselli also include Francesco Furini (1600–1649), whose paintings, for example, Magdalene in Vienna, are distinguished by their picturesque softness of the brush and the dreamy sentimentality of the mood. To the second generation of Rosselli's disciples belonged to Carlo Dolci (1616–1686), once exalted, now humiliated master, with all his mannerisms representing a kind of artistic personality. Only in his best paintings, as “St. Cecilia "and" Salome "in Dresden, mental mood corresponds to the unity of his colorful techniques, combining the refinement of local tones with hot chiaroscuro. Ordinary pictures of him, mostly belt images of saints, give the impression of variegation and rigidity, coldness and sweetness.

In Venice, Jacopo Palma the Younger (1544–1628), the cousin of Palma Vecchio, is a representative of the impotent transitional art. More natural, though more effeminate in the forms and colors of Alessandro Varotari (Padovanin) from Padua (1590–1650), nicknamed “the female Titian”. His best paintings, The Harlot and Judith in Rome, have always been among the favorite things of the crowd. The disciple of Varotari Pietro della Vecchia (1605–1678) sought to clothe the realistic types of Old Venetian brilliance of colors and harsh lighting. The beautiful Eclectic was the Veronese of Alessandro Turki, Orbetto (1582 to 1648), whose mythological and biblical scenes, often written on slate boards, combined skillful form language with old-Oldish combinations of colors. Procaccini, namely Ercole Senior (1520, died later than 1590), Camillo (1550–1627), Giulio Cesare (1548, died in 1626) and Ercole Procaccini Junior (1596–1676) tried to create a movement in Milan, completely similar to the direction of Carracci; however, their value and their students and followers are not enough on their own to occupy us here.

An independent master produced Modena in the person of Bartolommeo Scedoni (died in 1615), mentioned by Malvasia among the students of Carracci. Even more than his contemporaries, he was fond of sharp lighting effects, improving them as applied to landscape backgrounds, as his works show in the galleries of Modena, Dresden, Munich and Vienna. Ferrara in the person of Carlo Bononi (1569–1632) possessed a skillful, widely susceptible eclectic. Cremona is famous for its pleasant portraitist Sofonisboy Angishola (1528–1620), Pisa is also a portraitist for Artemisia Gentileschi (1590–1642), adopted in many courtyards. Her father, Orazio Lomi, nicknamed Gentileschi (1568–1646), was especially nominated by Schmerber, as in his paintings, for example, in the Annunciation of Turin, light and space are felt in a modern way.

Fig. 108. The Annunciation by Gentileschi.

The followers of Cambiaso, Giovanni Battista Pazzi (1552–1627) and Valerio Castelli (1625–1659), faithful to bright colors, transplanted into Genoa an eclectic trend not so much Bologna as Florentine and Milanese, but in Genoa, as in Naples, the victory remained for naturalistic or realistic course.

4. Caravaggio, naturalistic representative

Creativity of one of the most prominent painters of Italy at the beginning of the XVII century, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, represents a naturalistic direction in painting, sharply opposed to the style of Carracci. The Caravaggio School spread its influence throughout Italy, and its students and followers continued to develop this area over several generations.

At the head of the naturalistic or realistic movement in Italy (attempts to distinguish between the naturalistic and realistic areas of art seem unsuccessful to us), the passionate, distinctive personality of the Upper Italian by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1569–1609), who, after a long non-recognition, was given back due already Julius Meyer and Eisenman, and lately Schmerber and Callab provided an honorable place. It can be considered as probable that Caravaggio was in Venice in the early period of his life, where he studied Georges and Tintoretto. The written sources prove that he spent a short time in Rome as a pupil of Cavaliere d'Arpino. In any case, he soon became a conscious opposition to Arpino and Carracci. He is naturalistic already in the selection of topics. Genre paintings in natural size from the life of the people made him the chief master of this kind of painting, although Giorgione and Titian had already made their way in this direction. Naturalistic and his artless, often angular composition of historical scenes, his man-like folk types, his struggle with the problems of space and light, to which he subordinated his delicate natural sense of color. But his plastic brush sinking in colors often casts black shadows directly near the bright light, his types, though borrowed from the common people, were still only types, and his addiction to particular life situations did not compensate for the obvious natural lack of landscape perception. In short, Caravaggio was more a pioneer and a path indicator than a trailer. Generally distinguish his early Venetian, evenly reddish light from the color with the black shadows of his average period and from the late, sharply, as if from the basement of the escaping light. However, his works are difficult to date. Life-size genre paintings reflect these transformations in a whole series, starting with the famous “Lutheist” in the yellow dress of the Liechtenstein Gallery, then going on to the Louvre group of muzhikovykh musicians and ending with the amazing “Players in the cards” in Dresden, which we cannot take from him. The same sequence of development is revealed by his self-portrait in the Uffizi, the portrait of the Maltese in the Louvre and the male portrait in Budapest. From the usual religious and allegorical paintings of Caravaggio "Rest on the Way" and "Magdalen" in the Doria Gallery in Rome represent his bright early time, and both fascinating love allegories in Berlin - the middle period of its development. The heads of the saints of this master reflect the different phases of naturalism mentioned with black shadows. The series begins with powerful images of Matthew in San Luigi de Francesi in Rome and the Berlin Gallery. It is followed by "David" in the Borghese Gallery, "Christ in Emmaus" in London, "St. Sebastian "in Dresden. The series ends with his greatest creations of this kind: the touching "Standing in a coffin" in the Vatican, the enormous "Madonna with the rosary" in Vienna and the brightly lit from above "Assumption of Mary" in the Louvre, an amazingly powerful picture, stunning in its sense of reality.

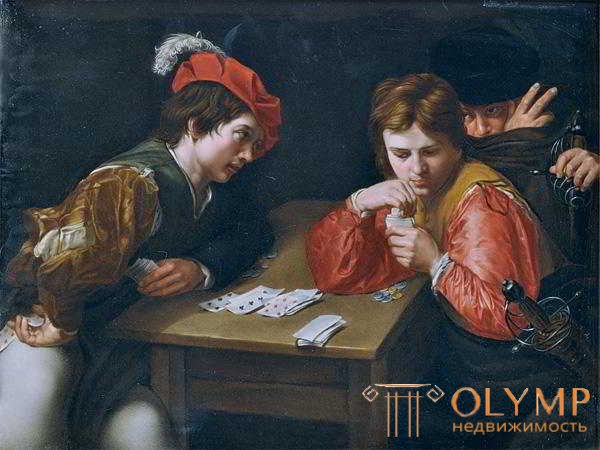

Fig. 109. “Card Players” by Caravaggio at the Royal Gallery in Dresden

If almost all of these paintings appeared in Rome, then Caravaggio made his last works in Naples, Malta and Messina. Peter's "abdication" at San Martino in Naples suggests that he continued to progress even further when he was beaten to death.

The influence of Caravaggio on the youth was irresistible. In Rome, he was joined by the pawnbroker Bartolommeo Manfredi (about 1580–1617) and the Venetian Carlo Saraceni (1585–1625). From Bologna the disciple of Carracci Leonello Spada moved from Caravaggio from Parma (1576–1622). He was followed by the born Roman Angelo Carosei (1585 to 1653). Giovanni Battista Carracciolo (1575–1641) in Naples, a disciple of the mannerist Francesco Imparato, succumbed to the influence of Caravaggio. But the disciple of Girolamo Imparato Andrea Vaccaro (1598–1670) and the disciple of Carracciolo Massimo Stationio (1585–1656) only sailed in the stream of Caravaggio in youth and soon anchored in the eclectic harbor of the Bolonians. On the contrary, the Syracusan Mario Menniti (1577 to 1640) was a true student of Caravaggio, who transferred the style of his teacher to Messina.

Little by little, Caravanjo created a school in all of Italy. Thanks to him and the resettled Netherlands, Rome first became the center of realistic aspirations. The Roman Domenico Feti (1589–1624), whose feature was represented by small paintings with landscapes and genre settings, such as “Proverbs of the Lord” in Dresden, was originally a pupil of Cigoli, but developed into a kind of master with natural shapes, balanced color and a smooth wide brush. In landscape genre paintings - leaving aside its Market in Vienna, Feti still adhered to ideal themes, while his fellow countryman Michelangelo Cherkvozzi (nicknamed by Michelangelo battles or “bombers”. Ed.) (1602–1660) was one of the first Italians, turned under the influence of the Netherlands to small-figure earthly scenes, framed by landscape. His images of the battle and folk scenes found in many galleries combine a confident picture with full mood lighting. In the school of Pietro Paolo Bonzi, called “il Gobbo dei Carracci”, aka “da Cortona” or “give frutti” (fruitmaker, 1570–1630), and Mario Nuzzi (“give fiori” - florist, 1603–1673), flower painters and dead nature, their tasks are united in the sense of understanding the decorative application of colorful effects.

In Genoa, the realist movement that flourished here under the distant influence of Caravaggio was led by Bernardo Strozzi (1581–1644), who later lived and died in Venice under the name “Prete Genovese” (“Venetian priest”). It is not as lively as Caravaggio, his brush is rougher and more angular, the paints are variegated; he is even less painter, and sometimes more rhetorical in the forms of his language, than Caravaggio. Numerous biblical, precisely Old Testament, compositions are not as interesting as bright-colored genre paintings in full size in the form of portraits, as are the cellist in Dresden, the cook in the Palazzo Rosso in Genoa, the poor in the Corsica palace in Rome. The multilateral Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (1616–1670), who migrated to Mantua, adjoins the realists as a painter of animals, but more by choice than by their execution.

5. The development of realism in Neapolitan painting

In the middle of the XVII century in the Neapolitan painting stood out a special direction of realism, largely due to the works of Giuseppe de Ribera and his followers.

The history of the Neapolitan art of the XVII century, darkened by the book of Dominici, was recently highlighted on the basis of primary sources by such a researcher as Salazaro; A detailed new work by V.Rolfs about the Neapolitan school appeared already during the printing of this volume. Realism is in the blood of southern Italians, however, in a suit

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)