When, after the fall of Babylon (in 538 BC), the whole of Asia Minor fell under the authority of the great Persian king Cyrus, and after the capture of Memphis (in 525 BC), the sacred country Nile recognized the dominion of Cambyses Cyrus, the Aryan race finally gained dominance on earth. Since the time of these sovereigns of the Achaemenid genus, Persian art comes into the field of vision of historical research. This relatively young art had no shortage of magnificence and virtues, but it had even less the right to be called folk art than the art of Egypt and Mesopotamia, which, although cultivated mainly by the will of the kings, nevertheless grew on national soil people. Ancient Persian art is rather only an artificial, official creation of a proud and victorious royal family, which was so ambitious that it tried to raise the level of culture even among the defeated nations. Therefore, it is not surprising that the growth of this art stopped as soon as the victories of Alexander the Great destroyed the power of the Persian sovereigns. Having developed, attaining prosperity and dying a violent death for 200 years (550–336 BC), the art of the Persians was, in essence, the art of a few generations.

But its distribution in space was much more extensive than in time. The ancient kingdoms of Medes and Elam were associated with Persia more durable and perennial bonds than the provinces that it later conquered. The ancient capitals of these states Ekbatana (Midia) and Susa (Elam) remained the favorite residences of the Persian kings, therefore we would have to consider these two cities as the main centers of Persian court art; meanwhile, in Ekbatan (Hamadan) from the remnants of the great epoch of Persia only two bases of the columns and the body of a lion were found. The treasures of the Parisian Louvre, mined by Delafoua in Susa, still seem to be more valuable from the open monuments of Persian art. But, taking care of the conquered capitals, the rulers of the Achaemenid house did not forget their homeland, which lay southeast. Cyrus preferred the ancestral residence of his ancestors, Pasargadae, the remains of which were found in the valley of the upper course of Polvara, near Meshed and Murghab.

But Darius founded a new magnificent city, 100 kilometers south of Pasargad, Persepol, for whose palaces the Persian style itself was first invented. What was started by Darius was continued by his son Xerxes. The ruins of Persepolis, they were investigated by Texier, Flandren, Coast, Stolz and Delafoy, still remain the most classical monument of Persian art.

We know little about the pre-Persian art of Ecbatana and Susa. Herodotus (I, 93) describes the city walls of Ecbatana. They went in seven rows, and the teeth of each row, towering above the teeth of the previous one, differed from them in their color, which was probably a borrowing from the multi-colored staining of the terraces of the Mesopotamian temples (cf. Fig. 180). On the contrary, Polybius (X, XVIII, 9-10), describing the ancient Median royal palace in Ekbatan, depicts its wooden structure, in which the columns, cornices and walls were lined with silver and gold, although they were only cedar and cypress. Such a wooden palace was tall, had a flat roof, slender, spacious columns with wide rectangular capitals and high and strong footings. The Persian peasant houses on the southern shore of the Caspian Sea, seen by Delafua in Mazenderan district, are still bearing the character of the buildings from which, it seems, this national style of the ancient Indian palaces appeared.

The image of the walls of Susa is on the same relief of Sardanapal in Kuyundzhik; Some reliefs on the rocks, richly inscribed, give us an idea of the pre-Persian style of sculpture of this city. One of them in terms of dress and posture of figures represents a distant resemblance to the monuments of the Hittites of Northern Syria; in the other one can clearly distinguish the style of later Babylonian art, which also owns small clay figures of naked goddesses, found both here and in Mesopotamia.

Of the works of the Achaemenid era, only the tombs and ruins of palaces are preserved everywhere. Tombs are either detached structures or carved into the rocks and decorated with facades, as in Egypt and Asia Minor. The palaces, the restoration of which is possible thanks to these, carved into the rocks, facades and preserved columns and remnants of the walls, served either for housing or for receptions: in fact, these were, as now, we see in East Asia, walled places with gardens, among which separate rooms were not united into one whole, as in Assyria, but stood one next to the other in the form of separate buildings. All of these were buildings with a flat roof on the columns (architrave construction), and the columns were tall, slender, widely spaced, and in their number and significance they played such an important role in palaces as no other nation has. Columns, corners and protrusions of the walls, shoals of doors, windows and niches, as well as the foundation and stairs, were hewn from stone, namely from solid, gray, sometimes casting yellow limestone of the Persian mountains. The walls themselves were made of bricks, usually only dried in the air, and sometimes just from solid clay. The entablature of the columns and the roof were carpentry. The wooden roof allowed to arrange columns widely; the shape of the stone columns resembled the wooden pillars that preceded them.

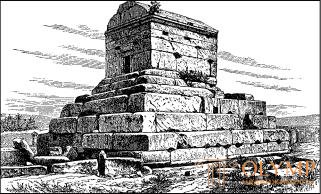

Fig. 233. The Tomb of Cyrus near Meshed-i-Murgab. By delafua

As the aforementioned modern-day peasant house in Mazandrani District represents for us the prototype of the Ecbatana's wooden palace of the Medes, this latter, in turn, according to Perrot, can be considered a prototype of such a Persian palace in which wooden pillars are replaced with stone columns. But for the development of individual forms of stone structures Iranian prototypes were insufficient. We will see how Persian court art used borrowings from the neighbors of Persia, and together with the Persian stone architecture we will also get acquainted with their plasticity - with the sculpture of reliefs, which are closely associated with this architecture.

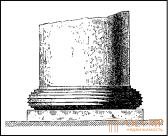

Fig. 234. The base of the Persian column from Pasargad. By delafua

Just as in Asia Minor tombstones preserved along with the gabled tombs in Pasargadah, not far from the Tomb of Cyrus, rises 12 meters from the ruins of the tombstone built of well-hewn stones, with columns protruding at the corners and topped with a toothed border. Quite the same, but better preserved tower near Persepolis is evidence that these towers had a roof in the shape of a truncated pyramid.

The disappearance of the splendor of the palace of Cyrus in Pasargadah is now testified only by one tall column; The base of its smooth rod is a simple round plate. Several other bases still rest in their former places; here and there, several corners of the stone walls and the lower parts of the doorposts, on which the legs of people and the vultures are visible, traces of the relief images located here, also survived. However, it is possible to conclude from these scant remains that the palace, the main features of which are repeated throughout Persia, consisted of a rectangular central hall with a ceiling supported by eight columns, a portico on four columns and side rooms on each side of the hall. The inscriptions leave no doubt that this was the palace of Cyrus; but in it, apparently, living quarters were not. Consequently, it was one of the above palaces, which served only for ceremonial receptions.

Of the monuments of sculpture in Pasargadi, the stone slab, preserved from a small building, deserves attention. On it is a relief image of the deified Cyrus (Fig. 235). The king is represented standing and turning to the right. On it is a narrow Assyrian dress, tightly attached to the body, without any folds, bordered with a braid with rosettes and fringe. Egyptian amon horns in a reduced form, fastened over the ears of Cyrus; also hit two pairs of large wings, like those of the Assyrian gods, behind his shoulders; original and headdress of the Egyptian gods over his head. Probably, this work was performed with the son of Cyrus, Cambise, who lived in Egypt for a long time and personifies the counting of the great conqueror as a god. But for this purpose, the artist did not have at his disposal the native formulas, as a result of which he held on to Assyrian and Egyptian motives. In general, the profile position of the body is transferred quite flawlessly; the chest is depicted as correctly as the head, and only the huge wings seem to hover on their own rather than organically attached to their backs.

Fig. 235. The relief of Cyrus in Pasargadae. By delafua

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)