Architecture

That architectural forms are largely dependent on building materials, is the truth that accompanied us from the Mesopotamian brick building to the Egyptian stone structure, from the ancient Greek marble building, originally imitated the wooden one, to the brick structures of Rome and the Upper Italian Lowland. The North German lowland, stretching from the Dutch coast of the North Sea to the sandbanks and bays of the Baltic Sea and to the northern tip of Jutland, was, like the Mesopotamian and Lombard plains, a country of brick buildings, and here it was possible to keep behind a brick building whose walls were not covered with anything and plastered only in some places intended for painting, his own architectonic pattern.

The art of firing bricks became known, however, in the North German lowland later than one would have expected. The oldest churches in this area, such as the church of the monastery Leutskau not far from the r. The Elbe (1147–1155) and the Cathedral in Havelberg (1135–1170), built from imported sandstone; built around 1000, the curious central church of sv. Michael in Schleswig, resting on twelve concentrically arranged pillars, composed of tuff. It was only in the middle of the 12th century that the art of burning brick was from Holland at the same time, and from Upper Italy - knowledge of the artistic forms of brick architecture. Features of the northern brick architecture are weak development of protrusions of any kind, intersecting arc friezes (Fig. 230) and the so-called trapezoid, or conical, capitals (Fig. 231), replacing themselves with cubic ones. In these capitals, semi-cones, pointing upward, fill the angles between the sides of the trapezium, set on their narrow base. From other ornamental motifs there are zigzags, teeth and rows of obliquely set bricks. In some places, as a building material, boulder granite was used, as we see it, for example, in construction in 1157–1160. partly of the vaulted church of Crewese. But the granite is too hard for it to be convenient to carve ornamental motifs. Romanesque antique leaf ornament and other side decorations, except when they were already cut down on imported sandstone slabs, could only be obtained by squeezing them into clay, which was then fired.

Fig. 230. Frieze, formed by two mutually intertwining arkaturami, in the Brandenburg Mark. Lubka

Fig. 231. Trapezoid capital in the Brandenburg Mark. By Muller and Motes

The main area of distribution of new, brick architecture was the Brandenburg Mark. We owe Adler the closest acquaintance with this architecture. Its most important monument - built in 1147-1152 years. Premonstrant Order Church. However, it is the most significant flat-roofed church of this style. In addition to the Saxon influence in it, the influence of the Girsau architectural school is also noticeable. This is a cruciform three-nave basilica with columns, two western towers, a three-nave chorus, ending in three absids, but with one more crypt, which, as is often found in the North German lowland, is arranged flush with the ground. The columns are made of molded bricks, but their abacus, decorated with palmettes, and also trapezoidal capitals are carved out of sandstone.

Farther north, in Lauenburg, is the most significant of the vaulted brick Romanesque churches of Germany, the Ratzeburg Cathedral - the basilica of a coherent system with pillars, which is an exact translation of the Brunswick Cathedral into a brick style. Ratzeburg cathedral looks like the magnificent Cathedral of Lübeck, and the latter is similar in style to the cathedral in Ribe.

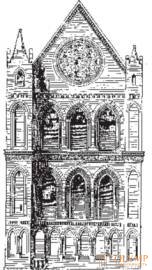

Fig. 232. The facade of the church in Linin. According to Adler

The transitional style in the North German lowland is again presented mainly by the Cistercian churches. The abbey church in Dobriluga has arched vaults, but is illuminated by circular-arched windows. The abbey church in Zinna (1170–1216), in Brandenburg, is built of boulder granite with brick arches; its arcades are lancet, the brackets, from which the arches of the side aisles rise, are decorated with an elegant ornament of baked clay. Among the most beautiful brick buildings of transitional style in Brandenburg are the monastery churches in Horin and Linin (fig. 232), in Pomerania, the churches Kolba and Eldena. In the monastic churches in Hood, in Oldenburg, and Pelplin, in Western Prussia, the side naves are extended to the straight end of the choir. The facades of the church in Linin and the ruins of the church in Goode, dismembered with pointed arches, are designed in free proportions and have very elegant details. Brick churches of this kind, impressing the already early Gothic, are distinguished by some chaste severity.

The Scandinavian countries, in which the Christian church structure was completed only in the second half of the twelfth century, received their church architecture — we leave aside for the time the wooden buildings from the south and the west. The German architectural style, moving from Schleswig to Jutland and the Danish islands, gradually turned into Scandinavian. The cathedral in Ribe, in the very south of Jutland, begun with the building in 1176, is made of Andernach stone and, accordingly, is equipped with Rhine-style emporians. The old royal cathedral in Röskilde, on the island of Zealand (Fig. 233), laid out in its present form in 1191, resembles not so much the Braunschweig and Ratzeburg cathedrals, as Shnaze and Lubka believed, as the Belgian churches of the Tournai cathedral type. Its chorus, equipped with a roundabout without a cappella rim and illuminated by circular-arched windows, is supported on the outside by strong buttresses, which alone indicate its belonging to the transitional style. The church in Westerwig, on the northwestern coast of Jutland, completed in 1197, is a circular-arched basilica, in which, in Saxon, two pillars follow each pillar; however, the heavy columns of this church resemble more English-romance than German-romance samples.

In the south of Sweden, the old Danish archbishop's cathedral in Lund can, with more right than the Röskild cathedral, be regarded as a typical Romanesque vaulted basilica of the German type. The capitals of its semi-columns are partly cubic, partly ornamented with leaves. The architecture laid down around 1150 is particularly luxurious, but the monastery church in Warngem, finished no doubt before 1200, its complex pillars, cross-sectional vaults and a semicircular choir without crown of chapels can be viewed as products of direct French influence.

Fig. 233. Part of the longitudinal body of the Ruskilde Cathedral. By Degio and Bezold

The architecture on the island of Gotland, whose main city, Visby, was the most important trading point of the Baltic Sea received a peculiar development. Along with one-nave and two-oil buildings here appear quite early - perhaps under the influence of Westphalian architecture - three-nave churches of the hall system, which is the church in Dalgem, consecrated in 1209. There is absolutely no transept in it. Tall and narrow circular-arched windows were common in the churches of Gotland as early as the 13th century, and the penetration of the pointed arch here did not lead to the Gothic structure. The supporting arches and costal arches are almost unknown here. Portals are especially richly decorated, namely original patterns carved in stone. Church of sv. Droitten and St. Clement in Visby has a classic hall arrangement with four pillars in the middle, dividing the whole room into nine compartments; on the contrary, the cathedral of this city, consecrated in 1225, is a three-nave hall church with a slightly elevated middle nave. This cathedral alone is open to worship, all other buildings of Visby, surrounded by thick walls with towers, turned into ruins, which makes it possible to call it northern Pompeii.

In Norway, Romanesque architecture was undoubtedly under Anglo-Norman influence. This is clearly seen in the example of Stavanger’s Cathedral (probably built between 1128 and 1150) with its heavy rounded pillars, with a folded form of capitals and portal arches decorated with a zigzag. Along with this, the church in Ringsacker, despite its massive round pillars, has a box-shaped vault above the middle nave and semi-spider vaults on the side aisles, as we saw in the French churches, while the Church of Our Lady in Bergen, founded by the Hanseatic, reminds itself again German prototypes. It is necessary to mention the national shrine of Norway, the Drontheim Cathedral, the enthusiastic description of which was made by Dietrichson. In this temple, little remained of the Romanesque stone structure (1161–1178), and a little more from the early Gothic (1183–1230); in both, the English influence was clearly expressed. Only in 1248 began the construction of a new Gothic building, to which we will return later.

Fig. 234. Wooden capital of the church in Urnø, in Norway. By Ruprich-Robert

Fig. 235. Decoration of the portal of the church in Urnø, in Norway. According to Dal

Fig. 236. The church in Gitterdal, in Norway. According to Dal

Thus, we see that none of the Scandinavian countries had any independent stone architectural style. Almost each of the Romanesque churches in these countries is a product of some other, continental, direction. The more distinctive is the Norwegian wooden architecture, which in the XIX century introduced us to the works of Dahl and Dietrichson. In wooden architecture, there are three wall constructions: tying logs in horizontal rows (frame), a construction from risers, that is, from vertically set pillars, and a half-timbered construction, or a “cell” construction, which is a combination of the first two systems. Wooden architecture almost everywhere preceded stone, but in Christian times it was only in those countries in which art began to be cultivated simultaneously with the advent of Christianity. In the Slavic countries and in most of the Germanic all the ancient churches, palaces and residential buildings were built of wood. Even Vitruvius argued that "Kolkhtsy are skilled in building log cabins, Gauls are in cell construction"; this agrees with the fact that the wooden churches that have survived to this day in Eastern Europe are built mostly from horizontally laid logs, whereas in Western Europe buildings from vertical posts prevail. In Eastern Europe there are a significant number of rural wooden churches, belonging, however, mainly to the later centuries. It is possible to trace how the wooden church building proceeded from Russia, Hungary, Moravia and Galicia through Silesia to Germany. In England, from the Anglo-Saxon time, only one is preserved, moreover, a very simple, wooden church built of risers, namely the church of Sts. Andrew in Grinstead (Essex), which nevertheless proves that the buildings of the vertical racks were brought to Norway along with Christianity from the British Isles. But then the buildings of this kind developed in Norway on their own. It is immediately evident that the people-shipbuilder began to build wooden churches here. The roofs of most such churches are keeled in shape and resemble an overturned ship; The features of all Norwegian carpentry craftsmanship are also borrowed from the ship's architecture, for example, joining by means of dowels, thorns (“to the tooth”) and braces. For all that, the style of the Norwegian wooden churches originally imitated stone architecture, as evidenced by the shape of columns (fig. 234) and circular arches connecting them in the oldest wooden church in Urneu, about 1090, on Zognefjord. Features characteristic of the principles of wooden architecture, developed only gradually. The basic form of these churches is basilic, but it is more consistent with the principles of wooden architecture that not only the middle nave is separated by columns from the side ones, but the rows of columns are repeated in the transverse direction, before the choir and in front of the entrance side; Wooden architecture, as well as the cold and rainy climate of Norway, correspond to covered high roofs and galleries arranged around the whole building on the poles, which, like the side naves, are covered with a lean-to roof and give the churches of this kind three-storeyed buildings. The dragons on the gables resemble the heads of dragons on the bows (inclined parallel bars on the bow) of the Viking ships. The ancient Irish-Saxon animal and ribbon weaving (see Fig. 82) is repeated in the ornaments of the portals; An example is the ornamentation of the portal of the ancient church in Urneu (Fig. 235). But after 1150, these decorations take on the character of rather Anglo-romance deciduous garlands with winged dragons. Fantastic masks adorning the capitals of the columns are characteristic of almost the entire Romanesque region. The Norwegian wooden architecture is perfectly characterized by the well-restored church of the XII century in Borgund (in Lørdal), on the walls of which there are still runic letters; it is not quite stylishly restored church in Gitterdale, in Telemarken (fig. 236). Both of these churches are crowned above the longitudinal hull by a small belvedere, which gives them a pyramid shape, both are above the apse, and the gitterdala church also has a round turret above the choir. Some of these small churches were moved to other places; for example, the church located in Vanga (Faldres), in 1844, was transferred to Silesia, in the Giant Mountains, where it now serves as the parish church of the village of Brukenberg, which itself consists mostly of wooden houses. This church is also crowned with a belvedere, enclosed by a covered gallery and decorated with intricate intricate carvings in the style of the time following 1150. Thanks to these details, the Norwegian wooden churches have the character of artistic and finished works.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)