The development of Chinese art was due in part to the above-mentioned external influences, in part, and, moreover, to a large extent, to the internal development of Chinese spiritual life. At the time when about the middle of VI century BC. e. in China, as well as in India and Greece, great thinkers and dreamers were bold innovators, the ancient state religion of the empire prescribed worship of Heaven, earth and ancestors. It resembled the religions of the Polynesian and American primitive tribes already familiar to us. But, as I. G. Plat proved, she lacked the desire to create myths, lacked the anthropomorphism of other peoples. Only the emperor had the right to offer sacrifices to Heaven. The sun, moon, and stars were considered heavenly spirits; mountains and rivers, forests and valleys, seas and streams were honored as earthly spirits. With the ancient pure religion, no idols or temples were required for prayer and sacrifice. The Temple of Heaven in Beijing now consists of large open-air terraces, not buildings.

The state construction rules of the first centuries of the Zhou dynasty (about 1000 BC. E.) Differ very little from those still in force today. Only the imperial palaces of the Zhou dynasty, judging by the ancient drawings and descriptions of poets, in contrast to the later palace buildings, which were scattered in a horizontal direction and consisted of terraces and towers, the floors of which were interconnected by external staircases, "rose to the heavenly clouds." Since these buildings resemble the massive terrace-like structures of Mesopotamia, its influence on the then Chinese architecture seems rather probable.

The fine art of the Chinese in this most ancient epoch is before us in jade and bronze articles. Jade vases that served religious purposes and objects plastically made of jade, which were worn as signs of ranks or as decorations, are mentioned in the XII century. BC e. There is an indication that as early as 1134 there was a special imperial official in charge of a jade shop. But on a par with gray and greenish jade, or poisonous, among the artistically processed materials in this initial era of China, just as in the prehistoric era of Europe, the main role was played by brilliant, like gold, bronze. Bronze vessels - perhaps the most ancient of Chinese works of art, preserved to our time. Only a few of them came to Europe, but these few copies are mostly not real ancient, original works, but later copies, which, however, due to the good faith with which the Chinese copy, give us a complete understanding of the ancient vessels considered sacred. Curious specimens of such bronze vessels are found in Paris, in the collection of Chernuski, and in Berlin, in the collection of Baron von Richthofen, part of which was transferred to the Museum of Ethnology. But they acquaint us with such vessels, mainly engraved on wood, drawings of old Chinese collection pointers, one of which, Po-ku-t'u, compiled in 1107-1111. n O., contains images and descriptions of 1206 bronze vessels of the Shang dynasty (1766-1122 BC), and the other - C-te'ing-kien, written only in 1749 AD. e., - drawings and descriptions of 1400 similar vases of the imperial collection of that time. Richthofen, Lippmann, and especially Geert published valuable notes on these catalogs in German. Being made by a part for religious purposes, part in order to serve as imperial honorary gifts, these vessels already with their forms, maintained in accordance with the prescribed prescriptions, as well as flat-relief decorations, clearly indicate their purpose. Each motive had its own symbolic meaning.

Vases intended for the blood of sacrificial animals were given the shape of these animals with strictly symmetrical parts of the body, and the receptacle of the vessel was arranged in the back of the figure. Images of a man during the Zhou dynasty was not yet.

Fig. 582. Chinese ornaments. According to Girth

Ornaments, which look like plants, on closer examination, as a rule, turn out to be decorated with animal motifs, of which here, as in the ornamentation of primitive peoples, the all-seeing eye is in the foreground. Along with animal motifs, the main role is also played by geometric ones. According to Fr. Geert, it is very likely that the Chinese meander, which, although it occurs more often singly or in pairs than as a continuous band, nevertheless constitutes the main element of the ancient Chinese ornamentation when filling the space, should be looked at as a symbolic image of thunder. Apparently, he also descended here from round forms (Fig. 582, a and b); developing further in a rounded form, a symbolic image of thunder appears simultaneously in twisting ornaments, in which two, three spiral tails and more rotate around one common center (c). These motifs are not always joined by distinct tail and serrated patterns. But the main feature of ancient Chinese animal symbolism is the combination of fabulous animals, showing the ardor of Chinese fantasy and in artistic terms. On ancient vessels, the most common is a huge, cat-like T'aut'ie, a symbol of gluttony. But soon, famous fairytale animals appeared behind her, of which the main thing - a dragon with a chameleon head, deer horns, bull ears, snake tail, eagle claws and fish scales - a monster with which in China is associated not with something terrible, but with grace. It serves as the personification of fertile water, clouds, mountain peaks, generally sky, and starting from the nearest period, from the Han dynasties, acquires the meaning of the symbol of imperial power and perfection. The closest thing to a dragon is its pheasant's head with a pheasant's head, a turtle's neck, the body of a peacock or a dragon and with outstretched wings. Subsequently, this figure became a symbol of the empresses. The third in this series is most common unicorn, like a deer (Ki-ling). Of non-fictional animals, the tortoise, wolverine and horse are symbolic. The ornamentation of a geometric character, sometimes covering the skin of a bronze animal, is amazing. Something similar we find in the art of primitive peoples in Madagascar. Of the three ancient Chinese bronze vessels depicted in this book, the first (Fig. 583) belongs to the Po-ku-t'u dynasty, Shang dynasty; the second (Fig. 584), originating from the collection of Richthofen and located in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology, gives an idea of the style of the Zhou dynasty; the third (fig. 585) - a sacrificial vessel in the form of a hare with hooks and meanders on the body; its image is taken from one newest Chinese catalog.

Fig. 583. Ancient Chinese Bronze Vessel of the Shang Dynasty. By von Richthofen

In the VI. BC e. Two wise men opened new paths for the spiritual life of the Chinese empire: Lao Tzu and Kun Tzu (Confucius). The first was born in 604, and the second - in 551 BC. e. Lao Tzu was a hermit who retired from the world. The original reason for all things was that his teaching exhibited a higher mind, called Tao. Confucius was a worldly sage; he taught his followers to make their life on earth happy with the help of mind, decorum, favor, and taste. Both wise men were recognized as saints after their death, and they both began to dedicate temples; but the real founder of the religion was only Lao Tzu, and his followers, the Taoists, to this day constitute the most populous and popular of the religious sects of China. As for Confucius, he remained faithful to the historical state religion. The temples dedicated to him, of which the most famous are in Beijing and Kiufeou, where the sage was born, are halls in his memory, devoid of any paintings and decorated only with his name and sayings.

The time of the Han dynasties (from 206 BC to 221 AD), generally still influenced by the teachings of Lao Tzu and Confucius, was replete with artistic aspirations.

Fig. 584. Ancient Chinese Bronze Vessel of the Zhou Dynasty. By von Richthofen

Fig. 585. Ancient Chinese sacrificial vessel in the form of a hare. According to Paleolog

There is no doubt that the original Chinese pottery art, to which the rotating circle was known in the previous epoch, was now making strides for success and although it did not even make real porcelain, but it already produced luxuriously painted stone glazed dishes. There is also no doubt that the invention of the paper in 105 AD e. It gave a new impetus to Chinese painting and painting, until then using only silk fabrics. But the most important thing that cannot be doubted is that in this era, Chinese art for the first time dared to depict human figures. It was also established that during the Han dynasties foreign influence had penetrated into Chinese art. Chinese "grape mirrors" testify to the Hellenistic influence, which was found during the first Han dynasty (from 206 BC to 25 CE), to which Fr. Geert. Although some of the original copies of such mirrors or later copies of them were in European museums, we are familiar with them mainly from the drawings by Po-ku-t'u: on the surface set aside for the ornament, the naturalistic Hellenistic wavy garland, intertwined with grape shoots, leaves and brushes; Between the tassels and the leaves, there are inserted figures of animals of various breeds, often depicted as they appear when looking at them from above. We saw something similar in Hellenistic-Roman, as well as in Hellenistic-Sassanian art, for example, in the Mashita Palace. There is no doubt that we are dealing here with the influence of the Hellenistic West; all that is asked is: how could this influence penetrate China? P. Reineke is inclined to see in this ornamentation the continuation of the Hellenistic elements of ancient Siberian art, which was in intercourse with the ancient Chinese. Other authors suggest direct Bactrian influence. In any case, in view of the works in question, we must recognize for Hellenism the influence on the development of natural plant and animal forms of Chinese ornamentation.

Fig. 586. Relief of Giao-t'ang-shana. According to Paleolog

Since 67 AD e. Buddhist statues of gods and paintings began to penetrate into China from India, but Chinese artists began to imitate them only after the younger Han dynasty. On the contrary, stone plastic images (Ed. Chavannes dedicated a special work to them) appeared during the Han dynasties. It is in their time that we find a rich, original sculpture in China, and with respect to these images, evidence of ancient texts is confirmed by travelers.

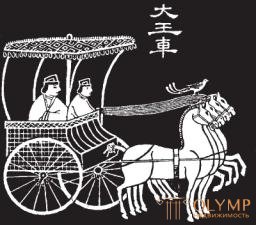

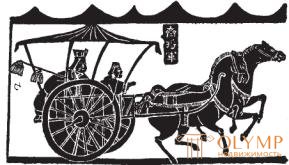

We learn from written sources that even during the senior Han dynasty, in the 2nd century AD BC e., the walls of palaces and tombstones were decorated with relief stone sculpture; but all surviving works of this kind, according to Chavannes, belong to the time of the younger Han dynasty, that is, they date back to the 2nd century AD e. All of them were found in ancient tombs, and, moreover, with few exceptions, in the province of Shantung; the heights of Giao-t'ang-shan and the “museum” at the foot of the U-che-shan mountain, near Kiasianga, became famous for their stone planks with sculptural images. Eight (and on the Chinese account 11) reliefs of Giao-t'ang-shana (Fig. 586) are among the most ancient. As a matter of fact, these are not reliefs, since only contours are deepened in them; large, teeming images on plots from Chinese history and mythology are located one above the other in rows on different planes; against the background representing mountains, bridges and buildings, the roofs of which do not yet have Chinese folds, we see long rows or hand-to-hand fights of warriors, on foot, on horseback, riding on two-wheeled chariots, and between them camels and elephants. There are also episodes of a peaceful, homely life. Everything is depicted without the slightest observance of perspective, in the inexpressive features characteristic of all primitive art, but everything has a national character; costumes and poses are Chinese, and the main movements are full of life. Especially the figures of horses with their round bodies and slender legs are distinguished by the marvelous force of the movement given to them when they are carrying something, are walking, trotting, or galloping.

Fig. 587. Relief of U-cheshan. According to Paleolog

Forty-six boards with reliefs in the "museum" at the foot of the U-che-shan mountain belong to various tombs of the U. surname. The existing opinion that there are reliefs of the gravestone of some U-leanga between them, the name of which is called by this whole group, has recently been disproved. Their content is taken from Chinese history and legends, partly from such rare legends in which sea animals and sea demons are found, and horses, horsemen and chariots always play the main role (fig. 587). In some places, large-leaved trees are found in the foreground; Attempts to transmit movements with greater freedom and vitality are often visible, even attempts to depict a horse in front, and a man in semi-profile. The paleologue is right in finding that all these boards belonging, undoubtedly, to the 2nd century AD e., not as ancient as the boards of Giao-t'ang-shan. Chavanne, believing that the later of these boards are very close to the oldest ones in terms of time, apparently did not take enough of the consideration of the difference in the style of images on those and others.

The same character as the gravestone of the family U has a board found with them, but subsequently transferred to the studio hall in Tsi-ning-chow, depicting Confucius's journey to Lao Tzu. All this sculpture seems to us quite clearly pre-Buddhist. Chavanne, in general, insistently denied that there was a reflection of foreign influences in her; Indeed, despite the fact that it has common features with all the "archaic" art, it in all respects, not only in the depicted scenes and costumes, but also in the forms and motives of the movement, apparently developed on national soil.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)