Babylon was still almost completely in ruins, when Nabopolasar awakened the ancient Euphrates kingdom to a new life. Few of the remaining cities of the state suffered less than the capital. What was not destroyed by the hand of the enemy, then died from neglect and poverty. Nabopolasar personally began directing the restoration of Babylon. He laid the enormous fortifications of the capital and set about building a new royal palace in it. However, only the successor of this sovereign, Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562), was destined to endow the New Babylonian kingdom with his own art. Not only in Babylon, but in all cities of the country, in Ur, Lars, Uruk, Nippur, Sippar, he restored the destroyed temples, renewed the fortress and sewer structures, decorated the palaces with the same luxury. Nebuchadnezzar considered as his real business not military campaigns, but constructions. Only with them was he proud of his inscriptions. And just like Nebuchadnezzar at the beginning of the kingdom of Babylon, Nabonidus (555-539) at the end of it, before it was conquered in 538 by the great Persian king Cyrus, tried to bring back the life and brilliance of the past millennia to Babylon. Novo-Babylonian art flourished no more than half a century, during which it could hardly have developed further, therefore the traces left by it are not particularly numerous; excavations of French and English archaeologists in Babylon did not lead to results rich in new data; more successful are the excavations carried out now on the site of the ancient world city by the German society of orientalists. Fortunately, the understanding of the wreckage preserved here is facilitated and replenished with written sources.

The huge quadrangle occupied by Babylon, according to Herodotus, had 120 stages (22 kilometers) in each side.

Outside, he was surrounded on all sides by a wide moat. The moat was followed by a giant wall built of burnt bricks, asphalt and layers of reed; Herodot determines its width at 50, and its height at 200 cubits. Later authors give smaller numbers; in any case, the height measurement of the wall included the towers, which Kteziy numbered 250. All the authors agree that it was possible to ride and turn around on four horses along the wall; The newest German excavations confirmed this data, since they found that the wall was 42 meters wide. The hundred gates in the wall, with all their pillars and cornices, were brass. That such gates were used in Babylon is proved by the half of the massive bronze door sill found by Rassam in Borsippa. This massive cast plate, decorated on the front side with quadrangular fields with a rosette in each of them, is in the British Museum. The Euphrates, which flowed through the city, divided it into two parts, they were interconnected by a bridge, the stone foundations of which "were immersed in depth with great skill", were fastened with iron spikes and supported a flat platform, arranged with the greatest skill of cedar, cypress and palm logs.

Fig. 192. Limestone debris from Al-Qasr. By Perrot and Shipie

The most important works of Novovavilon architecture are palaces and temples. Two royal palaces, facing each other on the opposite banks of the river, were interconnected by an underground passage with vaults arranged under the river bed. The palace of the left bank was surrounded by a triple row of walls and was distinguished by its size and magnificence. There were famous hanging gardens of Semiramis, ranked by the ancients among the seven wonders of the world. Nin and Semiramis, as the builders of Babylon, are, of course, the legendary creations of a written Greek history, and Diodorus, who described the hanging gardens in more detail after Ktezii, noticed that they were not built by Semiramis, but in a later era. We know that Nebuchadnezzar ordered these gardens for his wife Amitisa, originally from the Medes, with the intention of reminding her of the mountains of her homeland. Diodorus describes them as a terrace-like building, "rising like a mountain, a tier above the tier, so that it looked like a theater. The rows of walls supported these towering one above the other terraces ... on the highest wall was the upper garden terrace of the same height with the city walls ..." Strabo added that the terraces rested on the arches. To the capital buildings of Babylon belonged also a large temple of Bela - the famous Tower of Babel. Herodotus described her as an eyewitness. According to him, the walls surrounding the sanctuary were a square with 2 stages in each side (about 370 meters); "in the middle of this sacred fence stood a tower composed of all stone, having at the base of one stage (185 meters) in length and width; there was a second on the lower tower, a third on the second, etc., so that there were eight of all the towers , one above the other. Outside, a twisted staircase went from top to bottom all around the towers, and on the last tower was a large temple ... "Apparently, Herodotus described a yielding temple of a type we already know.

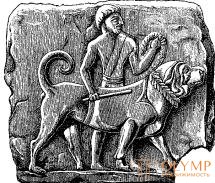

Fig. 193. Servant with a dog. Novovavilonskaya terracotta plate. By Maspero

Other arts developed in Babylon in close connection with architecture. We know about sculptures of the Babylonian gods only from literary sources. Herodotus and Diodorus reported on the huge gold and silver statues that adorn the temple described above on top of the Bela Tower. The Prophet Daniel (III, 1) also mentioned the colossal golden sculpture of Bela. Diodorus, relying on Kteziya, spoke about the copper statues of kings. Of the architectonical sculptural works, for example, in the British Museum, remains of limestone found in Al-Qasr (Fig. 192), depicting two bearded husbands with feather tiaras supporting the architrave beam in the form of atlantes.

Of course, decorative terracotta plates decorated with relief images served for decorative purposes; Rawlinson's Beers-Nimrud records are in the British Museum; On one of them, the half-naked servant leading a big dog on a leash is quite naturally represented (fig. 193).

The metal facing apparently played an even greater role in Babylon than in Nineveh. Philostratus wrote: "The palaces of the Babylonian kings shone from afar with their bronze clothing; women's quarters, premises for men and passages were decorated, instead of paintings, silvered or gilded, sometimes even with real gold images." The walls of the main palace were painted with paintings. On the middle wall were depicted natural flowers "all kinds of wild animals." The same is said about the inner walls and the towers on them. “The whole,” wrote Diodorus, “is a hunt with countless wild animals whose figures are four cubits long. Among them is Semiramis riding a horse, killing a panther with a dart, and King Ning spewing a lion next to it”. It is quite possible that the narrator took for the queen one of those beardless companions of the king, which are known to us from the works of Assyrian art. Excavations made in the XIX century, proved that these paintings were made of glazed brick. The art of painting a brick, covering it with glaze and making it the decoration of buildings was purely local in Babylon. The Assyrians made little use of this kind of painting and never achieved such mastery either in glazing or in obtaining magnificent tones of colors like the Babylonians. According to Oppert, Assyrian glaze refers to Babylonian, like watercolor in oil painting. The fact that the images on bricks of both peoples, due to the very method of painting with colors, somewhat rise above the background, mostly blue, does not in the least prevent us from classifying this kind of painting as flat images. The Assyrian limestone and alabaster reliefs in the hands of the New Babylonian artists themselves turned into paintings on brick. In the chambers of Babylon found a huge amount of fragments of glazed bricks, but never managed to lay out of them any whole picture. There are, however, parts of animals and people, the hooves of horses, the eyes and beards of people, parts of flowers and leaves, a network of scales that signify mountains, and spirals depicting water. Although most of the brick debris obtained by the Oppert drowned in the Tigris, however, in the British Museum and in the Louvre a sufficient number of similar pieces were collected so that we, by supplementing them with our imagination, could get an idea of the Assyrian reliefs of the times of Sinaherib and Ashurbanipal and mentally restore the pictures of hunting life that adorned the city walls of Babylon. The inscriptions were made in white paint on a blue background. Yellow, black and white paint here are the main ones, along with blue. Red paint is rare, more often - very dark yellow; The latest German posts mention a green background.

Few of the surviving works of decorative plastics to which we have pointed out are cylindrical seals, since they are of Babylonian origin, and numerous fragments of paintings on brick show that the New Babylonian style cannot be considered a particularly successful development of the Mesopotamian style that surpassed the Assyrian. Only in relation to the general course of art in the considered epoch, in some fragments, a somewhat greater flexibility of the language of forms is felt. If glazed brick and metals were more widely used in the ornamentation of Babylon than in the ornament of Assyria, which had rich quarries nearby, then this should be explained not so much by the spirit of the times as by the nature of the nature of Middle and Southern Mesopotamia.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)