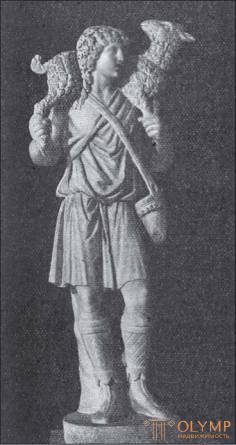

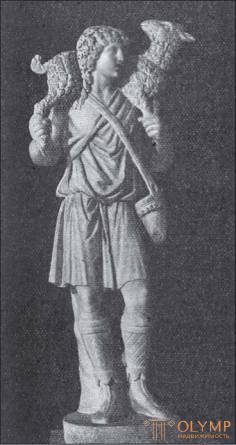

Antique classical art has reached its highest expression in the plastic. But the more charms there were in the sculptures of polytheism, the more carefully the Christians of the first centuries avoided impersonating their God in statues. The fact that Emperor Alexander Severus placed sculptural images of Abraham and Christ in his home sanctuary (Larariya) next to the statue of Orpheus, of course, does not contradict what was just said. Therefore, it was already easy to replace the Savior with the Good Shepherd by Christian round plastic, because the artistic motif of a person carrying a ram, calf, etc. on his shoulders was no stranger to classical sculpture. Suffice it to recall at least Hermes with a ram on his shoulders, the product of Kalamis (see vol. 1, Greek sculpture), and from those preserved to our time - such statues as “Moskhor” of the Acropolis Museum in Athens (see vol. 1, fig. 290). Of the sculptural images of the Good Shepherd that have come down to us, the oldest, and moreover, the best preserved ones, a small marble statue of the Lateran Museum must be recognized (Fig. 7). The young, long-wise shepherd, whose nobly delineated head is turned in profile, wears a short sleeveless tunic (exomidus) that leaves his right shoulder exposed. In his right hand, he holds the rear, in his left - the front legs of a sheep, lying on his shoulders. The good work of this graceful figurine makes you attribute it to the first decades of the 3rd century.

Fig. 7. Good Shepherd. Marble statuette. With photos Alinari

Of course, the ancient Christians were not forbidden to perpetuate in the sculpture of their relatives, especially honored co-religionists and martyrs, who soon became saints. But to the preconstantine time only one seated marble statue of St. Hippolyta, stored in the Lateran Museum.

The Christian relief sculpture of this early era introduces us to the field of art dedicated to honoring the dead. Marble sarcophagi from the II. play an important role in Roman sculpture, both pagan and Christian. Christians inherited their aversion to burning corpses from Jews. The ancient tomb carved into the rock turned into a portable coffin from a valuable stone that served the noble imperishable shell for the deceased. A model of the early, simpler style of Christian relief is the marble sarcophagus of Libya Primitives in the Louvre Museum in Paris. The front side of this sarcophagus is decorated with wavy grooves (shears), which were so loved then carved on the sarcophagi; in the free middle quadrangle, under the epitaph, the Good Shepherd is represented among the symbolic images of fish and anchor. On the one hand, more developed, and on the other hand, imbued with the ancient spirit are embossed images on the sarcophagus from La Gayolle in Brignoly seminary. In the middle is depicted the dead, in the form of a boy, and his tutor. Then, next to the Christian symbolic images of the anglerfish, orants and the Good Shepherd, we suddenly met the pagan sun god in a radiant crown. Le Blanc considered this beautiful sculpture to be the Greek work of the end of the II century. As a third, somewhat later sample of the ancient Christian relief plastics, one should point to the “Ion Sarcophagus” in the Lateran Museum (Fig. 8), the entire front side of which is divided into two planes and decorated with biblical compositions. The history of Jonah Ave, occupying the foreground, is designed according to the principles of a picturesque perspective.

Fig. 8. The sarcophagus of Jonah. With photos Alinari

We see that the ancient Christian and painting, and plastic reproduced a rather limited number of biblical scenes; in view of this, the theological school of archeologists teaches that in the first centuries of Christianity the only criterion for the selection of subjects was the possibility of their symbolic interpretation. Moreover, the prophetic meaning of the Old Testament events, such as, for example, the story of Jonah, is usually generalized to all the others. However, while some of the scholars of this school attributed to each biblical composition a number of very different allegorical meanings, others, headed by Viktor Schulz, being supporters of the so-called sepulkralnoy theory, see everywhere an indication of death and resurrection from the dead. This theory agrees perfectly with the first great French scientist Edmond Le Blanc and developed further Ezh. Munz and F.-X. Kraus interesting idea that the biblical compositions of catacomb painting and sarcophagi are illustrations of individual requests for funeral prayers, in which we meet the same examples of Delight Hand deliveries, alternating in addition in the same sequence (“Save, Lord, the soul of your slave, as You saved Noah from the flood ... how you saved Jonah from the belly of the whale ... how you saved Isaac from the hand of Abraham ... how you saved Susanna from a false accusation (etc.). However, it is impossible to prove that these petitions were included in the prayers before the corresponding scenes began to be depicted on the walls of the catacombs; in any case, there are several ancient Christian biblical compositions, such as, for example, “The Adoration of the Magi”, which cannot be attributed to a similar origin. In fact, with the exception of the deliberately missed Passion of Christ, we find reproduced almost all those episodes of the Sacred History that made a deep impression on each of us during our school years. Therefore, we cannot agree with the opinion that pious biblical stories were clothed in visible forms and colors not for their own sake. It is only fair that the art of the first centuries of Christianity had not yet thought of reproducing all the major events of biblical history in a sequence of time and in a systematic order; We also will not deny that when choosing scenes, on the one hand, parallelism between the Old Testament and the New Testament was taken into consideration, and on the other, preference was given to subjects that were most instructive from a Christian point of view. Only the scenes of the Passion of the Lord and the torment were expelled from these places of eternal peace.

For the history of art, more important is the question: is Rome really the artistic homeland of all these early Christian images, preserved mainly on its soil? We saw (see v. 1, Vol. 4, I, 2, II) that in the Roman-Hellenistic era of pagan antiquity, the Hellenistic element, feeding on Eastern influences, was everywhere stronger than the Roman; consequently, we have no reason to think that in the ancient Christian era of Rome this attitude suddenly became the opposite. After all, Greek was both the language of the New Testament, and the original church language of Rome, many Christian catacomb inscriptions were written in Greek, and in general Christianity in Rome developed not earlier than in the ancient cultural centers of the Hellenistic and even farther East. The Hellenistic East was undoubtedly the cradle of Christian art forms.

In any case, the modest Christian masters of the era of persecution, inspired by faith, were able, with the most insignificant means, to cope amazingly well with the tasks assigned to them. The seeds of Christian art were not only sown, but sprouted; as soon as the sun of tolerance had risen above this art, it had to, - of course, not rising above the artistic level of the epoch of decline, - to produce brilliant fruits.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)