The remnants of the works of Assyrian art, destroyed and buried as a result of sudden catastrophes, for two thousand years rested with undisturbed sleep under the hills of garbage devoid of any vegetation, and only in the second half of the XIX century. came to light thanks to the costly excavation of the French and the British. In Ashshur (Kalekh-Shergat), the birthplace of the primitive god of the same name and the northern Semites, who received the name of Assyrians from her, who was on the right bank of the Tigris, some remnants of ancient Assyrian art monuments were discovered. The results of the excavations of Nineveh, the later capital of Assyria, which lay on the left bank of the Upper Tigris, the beloved city of the great goddess Ishtar, were far more fruitful. In Nineveh itself, on the ruins of which now stand in front of the city of Mossula of Kuyundzhik and Nebi-Yunus, in Kalah (now Nimrude), south of Nineveh, and in Imgur-Bela, now Balavat, east of Nineveh, the Englishmen A.G. Layard, V. Kenneth Loftus, Gormuzd Rassam and George Smith made great, extremely important discoveries, the main results of which were received at the British Museum in London. In Dur-Sharrukin (Horsabad), north of Nineveh, the excavations were made by the French Bott and Flandin, Plas and Tom, therefore the works of art found there are in the Louvre Museum, in Paris.

Fig. 163. The boundary of Nebuchadnezzar. With a photo of Thompson

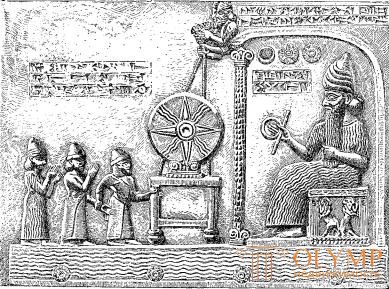

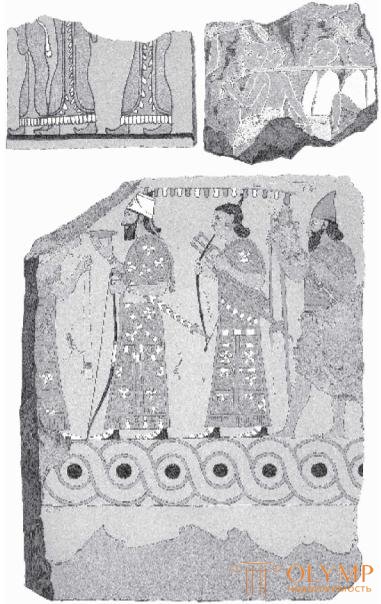

Fig. 164. Worship to the sun god. Relief. By Perrot and Shipie

The Assyrians, who once inhabited these places, strong and muscular, lovers of war and hunting, poured new spirit into the decrepit Mesopotamian art of the 9th-7th centuries BC. e., and although this jet was not very clean, but still was stronger and more lively and fresh. Of course, the Assyrians were conscious of the flesh and blood of the Babylonians, to whom they owed both religion, state institutions, science and literature, and the main features of art; but they did not disdain to borrow some particular forms of ornamentation from their distant relatives, the Egyptians. But the very fact of the further development of art on the banks of the Tigris in the era of the greatest prosperity of the Assyrian state, which lasted a quarter of a millennium (884-626 BC), proves that the northern Mesopotamians consciously went their own way; indeed, works of Assyrian art occupy a completely separate position among similar works left over from all the peoples of the world, as a result of which Assyrians cannot be called imitators in the common sense of the word. For example, winged lions and wingless bulls with human heads, standing in the form of high-relief colossi on guard at the entrances to Assyrian palaces, in their mythological character and significance could be of Babylonian origin. But if their use as symbols and decorative figures were among the Babylonians as widespread as among the Assyrians, they would not be discovered on the basis of Assyrian soil alone. Limestone or alabaster slabs with relief images of various episodes from the king’s life, placed one next to the other and stretched in rows along the lower part of the walls in the courtyards, in the aisles and in the halls of the palaces of Assyrian sovereigns, most clearly indicate the national Assyrian development of Mesopotamian art, although not It is doubtful that the style of these reliefs was formed in Babylon.

The most direct connection between Assyrian art and Babylonian art is visible in architecture , to which, in one way or another, almost all the artistic monuments of Assyria still open to the present. And in this country, the main building materials were stamped clay, brick dried in the sun, brick in significant places, burned in fire, and in some places glazed. The Assyrian temples, which were called Tsigurat, were, just like the Chaldean and Babylonian, massive, terraced-shaped buildings that narrowed upwards. But the rectangular base that prevailed in the south of Mesopotamia, here in the north, gave way to a square one, which got its beginning in Middle Mesopotamia. Like the palace of King Gudea in Sirpurle, about which we spoke above, the palaces consisted of a greater or lesser number of courtyards, each of which, together with the halls and chambers that appeared on it, was one closed whole. Several such departments, usually three, premises for men, women and household needs, were enclosed by one common wall with quadrilateral jagged towers protruding from it and with massive entrance gates and formed one building topped with battlements on a wide-spread dais, on which double staircases led and ramps. The extensive outer surface of the walls of the palaces, as in Ancient Chaldea, on the main façade was dissected by a system of recesses, the concessive profile of which, of course, due to the nature of the brick structures, corresponded to a double or triple row of teeth, arranged in steps. Ancient Haldean division of the facade into parts by round pillars, placed one next to the other, can also be found in Assyria. The lower upper floors, which opened onto a flat roof, looked like only towers on separate protrusions of the walls; windows or galleries with columns appeared, apparently, only in such superstructures on the walls and above the gate. However, there is no shortage of signs of further development compared with the ancient Babylonian architecture. First of all, it should be noted that the Assyrians used the vault much more often than the ancient Chaldeans of the south. Julius Oppert said: "Even in the current Babylon, buildings are built of brick and wooden pillars, as opposed to the new Nineveh (Mosul), where arches are made of raw brick."

In the Assyrian ruins, distinct parts of the vault vault are preserved, on the one hand, over the span of the gates of the city walls, and on the other, in the drainage canals, in which you can see either circular, elliptical, or pointed vault. Pieces of masonry, which could be taken only for the remains of collapsed vaults, were also found in the palace of Horsabad. Gates and doors, as a rule, had an arc-shaped top, but there are also doors with a straight top. Korobov vaults, apparently, covered the aisles and oblong main halls of palaces. French researchers. from the times of Plas and Tom, they claimed that some of the square halls had a dome cover. The reliefs from Kuyundzhik, the British Museum, depict small buildings (Fig. 165), proving that the dome-shaped buildings were not alien to the Assyrians. However, on other plates with images of Assyrian palaces, except for Armenian buildings with a gable, we see only buildings with a flat roof. In any case, such a roof, arranged on wooden beams, on top of which the floor is made of broken clay, is a general rule in the Assyrian construction business, as is confirmed by the fact that Layard constantly found heaps of ash from the charred beams during his excavations, as well as that the inscriptions of the kings say about cedar logs, which were brought to the buildings.

Fig. 165. Relief from the Sinaheriba Palace in Kuyundzhik. By Laird (II, tab. 17)

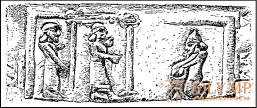

Fig. 166. Bronze relief from Balavat. By Perrot and Shipie

Stone pillars, as far as can be judged by the few fragments that remained from them, were used in the construction of Assyrian palaces only in the above-mentioned side places or as decorations for the outer surface of the walls. However, the image inside the house is on the same bronze relief found in Balavat (Fig. 166), just like the bronze cladding of a wooden column discovered by Plas in one of the courtyards in Horsabad, and finally the inscriptions dismantled by Meissner and Rost, one of which According to Sinaherib, he ordered columns to be supported on the ceiling in the same room on the lower floor, showing that the wooden columns were not alien to the Assyrians as supports. In any case, the columns in Assyria served their purpose better in those similar to tents, light small temples (aediculae, pavilions, kiosks), which in it, as in Egypt, existed along with massive structures, known to us mainly from the images on slabs with reliefs than in monumental buildings.

Fig. 167. Assyrian relief from Nimrud. By Laird (I, tab. 30)

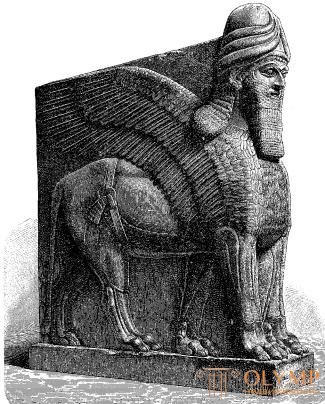

The image of this tent is found in the northwestern palace at Nimrud (Fig. 167). The upper ends of the supports presented here freely go outside. The capital with volutes, which is visible on the left side in the figure, strikingly resembles such capitals that were found in Egyptian painting (see Fig. 99, f, g, and). Two capitals are also peculiar, to the right, with volutes and facing to each other figures of a stone ram on supports placed above volutes. Based on this motive, Perro sees in the Assyrian voluntarily, both here and elsewhere, an imitation of the horns of a stone ram. However, such an explanation of the origin of volutes, in the sense of general position, is unlikely. On the Horsabad and Kuyunjik reliefs, small temples do not appear as tents, but stone buildings; their columns, as elsewhere in Assyria, are round and smooth. Volutes of their capitals are doubled, put one above another. Finally, the relief in the British Museum, depicting the sun god in his temple with columns, proves that the volute with a volute was used in Late Babylonian art (cf. Fig. 164) and that, therefore, it cannot be looked upon as an Assyrian invention. But it is especially incredible assumption that it originated from the Egyptian palm-like capitals. However, in the Assyrian architecture there are types of columns belonging to it alone. This includes the Horsabad column with a capital in the form of a flattened ball (fig. 168), decorated with two crowns of arcs spanning one another; This also includes the base of the column found in Kuyundzhik, which has a similar shape and similar decoration; this footstool rests on the back of a winged bull with a human head. This also includes a fragment of the base from Nimrud in the form of a winged sphinx of semi-Egyptian character (Fig. 169). That the feet of the columns really gave the appearance of these fantastic animals, as it was done later in medieval Europe, can be seen from one relief found in Kuyundzhik, the British Museum. The foot of the columns of the building on this relief, having the form of round pillows, rest on the backs of animals, which stand in pairs, one against the other. The bottom edge of this stand is ornamented with stepped teeth. There is no doubt that all these forms, with the exception of the Sphinx, are of Mesopotamian origin.

Fig. 169. Assyrian winged sphinx. Stand under the column. By Laird (I, tab. 93)

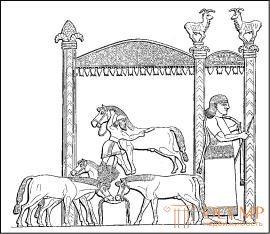

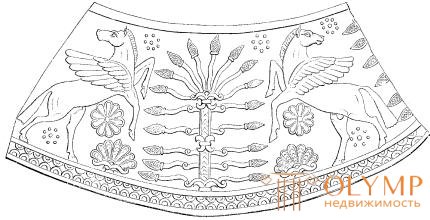

Fig. 170. Assyrian winged horses and the sacred tree. By Laird (I, tab. 50)

Fig. 168. Capital in the form of a flattened ball from Horsabad. By Perrot and Shipie

So, in terms of the main Assyrian ornamental motifs, we have already become acquainted with two- or three-stage teeth, also appearing in the form of rows, and circular arches of crowns, which had the most diverse use. In addition, a simple wall of intersecting lines is found among geometrical figures, and the rafters motif was used especially often to revive long strips. Of the motives of a purely technical origin, the ribbon and weaving that we already saw in Ancient Chaldea were a root attribute of Mesopotamia (cf. fig. 154). In addition, fabulous winged animals, sometimes winged bulls and horses (fig. 170) or animals in their natural form, sometimes depicted standing against one another, as in coats of arms, now fighting among themselves, and forming long rows, played an important role in Mesopotamian ornamentation. . It was not with the motives of the vegetable kingdom. To the idea of a rosette and here are ornamental figures of different origin. Jagged stars and concentric circles, sometimes bordered by small circular elevations, as we have already seen in Ancient Chaldea, are among the astronomical motifs. The most commonly used in Assyria rosette, borrowed from the vegetable kingdom, has the appearance of a star-shaped flower, if you look at it from above, like an ordinary sunflower or a daisy. In a later Assyrian relief, we see its distinct image in the form of a flower on a long stem (cf. fig. 189). The oldest surviving Mesopotamian rosettes placed on the tiara of King Marduk-nadin-ahi, or Nebuchadnezzar I, XII century BC. e. (cf. fig. 164). In any case, in the decoration of Egyptian ceilings, it is found even earlier. But the sample for this motive is so under the hands of one and all that a similar ornament could be invented both in Egypt and in Mesopotamia completely independently. It is not necessary, however, to mix the socket with the four-leaf and three-leaf. Along with the rosette borrowed from the plant kingdom, palmette plays a prominent role in Assyrian ornamentation, and a fan of straightened leaves. As a rule, its individual leaves are decorated with stripes and all come out together from the likeness of a floral cup with small curls that resembles similar Egyptian figures. Downward, the stems continue in the form of arcuately curved ribbons, on which a number of individual palmettes are located. Sometimes in such rows the palmette alternates with animal figures, sometimes the animal figure is depicted on its top. Delafua and Goodyear are hardly right in reducing this Assyrian palmette, which, however, the Persians subsequently saw as the silhouette of a real palm-top, to the so-called Egyptian palmette; this is all the less likely because in the Old Dutch period it was not possible to open its presence anywhere. In any case, the Assyrians created as a favorite ornament, along with a rosette, their own palmette with a very characteristic schematic outline. Among the rosettes and palmettes, as well as independently of them, sometimes there is a figure on a long stem, pointed upward, like a kidney or fruit, which - perhaps, quite mistakenly - was called a cedar cone, and another figure, round, in the middle with light stripes on a dark background, topped with three leaflets above, having the appearance of a kidney or fetus, also called, probably also incorrectly, pomegranate apple (Fig. 171). Obviously, both of these figures have nothing to do with the Egyptian lotus, although, as we will see below, this last one did indeed belong to Assyrian ornamentation and, without any alteration, in the form of a flower or flower buds, was alternately used in rows of ornaments. It cannot be denied that the Assyrian floral ornamentation itself is similar to Egyptian; but the manner of comparing the above forms with ribbon-like and weaving motifs, on the one hand, and with figures from the animal kingdom, on the other, is quite Assyrian in nature, and no one, in relation to the general impression, mixes Assyrian ornaments with Egyptian ones. From among the symbolic ornaments of Assyria, the winged solar disk is indeed borrowed from Egypt. But the image on this disc of a deity in the image of a bearded husband is already again of pure Mesopotamian origin (Fig. 172). Equally of Asian origin, the sacred tree is a splendid combination of the above-mentioned palmettes and so-called cedar motifs, combined in various ways (see fig. 170 and 172). The meaning of this image is not clear; but since on both sides there were winged spirits, figures of people or animals, in heraldic style, then, in all likelihood, it had some kind of religious significance.

Fig. 171. Assyrian ornament with weaving and pomegranate apples. By Perrot and Shipie

Embroidery, which decorated clothes, depicted on stone reliefs, give us a very clear general idea of all these motifs and at the same time - a clear concept of the equally high status of embroidery in Assyrian art-craft industries, as in Babylon in the XII century. BC e. On the contrary, the art of pottery, apparently, never played an important role in Assyria. Ornament of Assyrian vessels - simple geometric; however, Layard described fragments of an earthen vessel constituting an exception to this rule and decorated with pure Assyrian ornaments, namely stripes, palmettos, pomegranate apples.

Fig. 172. Winged sun disk with an Assyrian deity. By Laird (I, tab. 163)

Luxurious vessels were made mostly of bronze and decorated with engraving, gilding, gold and silver display in the form of concentric circles, and nowhere so clearly as on the vessels of this kind, there is no struggle of Asian motifs with those who have penetrated from Egypt.

Переработка ассирийцами различных чужих элементов их орнаментики в одно ясное сильное целое, очевидно, была художественным делом самого этого народа. Но до величайшего совершенства он дошел в общем декоративном убранстве ворот, коридоров, дворов и залов своих царских дворцов, где не оставалось ничего не украшенным и, по всей вероятности, не иллюминированным. Деревянные ворота и двери часто были обиты чеканной бронзой. Вообще, по заявлениям древних авторов, обшивка металлическими листами играла большую роль в украшении стен, нежели об этом можно судить по сохранившимся памятникам. Стены, сложенные из глины и просушенного на солнце кирпича, несмотря на свою толщину, были недостаточно прочны для того, чтобы выносить на верхних своих частях облицовку металлом или камнем. Облицовка состояла здесь или из глазурованного кирпича, из которого составлялись картины и большие надписи, или из штукатурки, расписанной красками. Только внизу, у самого пола, можно было отделывать стены плитами известняка или алебастра с раскрашенными рельефными изображениями, составляющими гордость ассирийского искусства. Близость гор давала ассирийцам, в прямую противоположность с вавилонянами, возможность добывать плиты. Этот материал обусловливал развитие местного искусства. Большие каменные рельефные изваяния исторического содержания имели у ассирийцев чисто национальный характер, и по ним-то, главным образом, мы можем проследить ход развития ассирийского искусства.

Written sources give only a scant concept of the works of Assyrian art between 1300 and 900. BC er the monuments of Assyrian art still preserved from this epoch and even more scanty. We know that even Salmanasar I (about 1300 BC), along with Ashur and Nineveh, founded the third capital of the kingdom, Kalah, and built a terrace-like temple; in all likelihood, the remains of this temple have reached us in the ruins of brick walls lined with stone slabs, which were opened by the Layard in Nimrud. We also know that Tiglatpalasar I, "the first of the great Assyrian conquerors," as Ed calls him. Meyer erected several temples in ancient Ashshur and restored others (around 1100 BC); Rawlinson's bad design introduces us to his image on a weathered relief, preserved next to the inscription on a rock near the sources of the Tiger. We know that the son of Tiglatpalasar, Ashshurbelkala, built himself a palace in Nineveh; his name is inscribed on the torso of a naked female figure badly made in relation to proportionality, the British Museum, which, as such, is quite exceptional among Assyrian sculptures. Finally, we are told that in the IX century BC. e. Assyrian governors ruled the lower valley of the Khabor; and indeed, Layard found here, in Arban, remains of an ancient Assyrian palace, four winged bulls with human heads, a lion with an open maw and a profile image of a warrior of a slightly convex work. In these works, a thorough, petty performance of hair, braided in small identical bunches, is especially characteristic.

The history of Assyrian art, in fact, begins only with the reign of great Ashshurnasirpala (884-860 BC), who transferred his residence from Ashshur to Kalah and erected there, to the south of the terrace-like temple, a gigantic palace known as the north-western Nimrud Palace. Two entrance gates from the north and the gate from the south and west led to its long, narrow main hall. On guard of each gate of the north, long side stood on a pair of sculptures of winged lions with a man's head and - unusually - with human hands; at the doors of the western, narrow side there were winged lions with a human head, but without arms, at the southern doors there were winged bulls with a human head, which were later found most often. The idea behind these images is clear enough. The unearthly patron spirit is personified in an image made up of body parts of the most powerful earth creatures. The head of a thinking man is attached to the wings of an eagle, the spine of a bull, the paws of a lion. Characterized by a winged lion with the head of a man from the palace of Ashshurnasirpala, the British Museum (Fig. 173). First of all, in all these guards of the Assyrian gates, the originality of the image of five paws instead of four is striking: due to the fact that these sculptures were placed at the corners formed by the walls, they were executed in such a way that from the front they seemed like real round sculptures; but in order to preserve the entire shape of the whole figure, when looking at it from the side, that front leg, which adjoins the wall, doubled. In an apology to this deviation from nature, it must be said that the fifth leg was not visible when looking at the figure, either from the front or the side. The headdress of this winged lion consists of a tiara with horns depicted on it, which is generally inherent in Assyrian gods; protruding eyebrows and large wide-open eyes that have grown together over the bridge of the nose are inherited by Assyrian statues from the ancient Haldean; the oval of the face, the fleshy cheeks, and the humped nose are the distinctive features of the Semitic type, repeated throughout Assyrian art without special individualization. Long, thick hair on the head and beard form a set of small, regular spiral curls - the reception of the image of hair, which continued in the sculpture of Greece in its ancient era. The lion paws of this fantastic creature represent an exaggerated designation of muscles and tendons, which was especially clearly expressed in this ancient work of Kalah-Nimrud art.

Fig. 173. Winged lion from the palace Ashurnasirpala. From the photo of Munsell

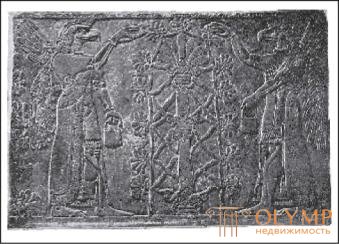

Actually the reliefs of the halls of the north-western palace acquaint us with all the content and language of the forms of Assyrian art. Colossal spirits in the form of winged men stand as guardians of the king, whom eunuchs serve. Eagle-headed gods worship a sacred tree (fig. 174). The long sides of the main hall were decorated with two located one above the other and separated by a strip with an inscription in rows of images of the life and deeds of the monarch. We see him riding on a hunting chariot and killing wild animals (Fig. 175), making a libation in honor of the gods on the occasion of a successful hunt for a lion or a wild bull, spending life in close contact with winged celestials, who are depicted with a headdress decorated with horns or with eagle heads. We see how the king, standing on his battle chariot, fights under the ramparts of the enemy fortress, as he crosses the river, accompanied by warriors, floating with the help of inflated bubbles, as victoriously returns home, met by musicians.

Fig. 174. Sacred tree and deities with an eagle head. Assyrian relief. From the photo of Munsell

Most of these reliefs are in the British Museum, but some of them also went to the Berlin and Dresden museums. All of them bear a peculiar imprint of the most ancient Assyrian relief style, represent an excellent, slightly convex work with a chisel and depict all the figures constantly in profile position. The gods, as well as the kings and even dignitaries of the monarchy are always represented with long hair and rich beards; the servants, the workers, the common people, and especially the eunuchs, wear long hair, but lack a beard. Female figures are only crying on the walls or in the processions of captives. The eyes are transmitted even without the slightest hint of plasticity of the eyeball. Long clothes without folds, sometimes trimmed with a heavy fringe with tassels, and sometimes richly embroidered, cover most of the whole strong, broad-shouldered, albeit somewhat stocky body. There, where the naked body acts, as, for example, on hands and legs, anatomically exact production of muscles and tendons, to which we have already pointed, is observed. Completely nude male figures are found only in the images of dead and robbed enemies or pursued by the enemy, sailing the river. In these cases, the sense of form in the entire body of the organization of the nude body is underdeveloped. In this respect, the Egyptians stood above the Assyrians. Nevertheless, some particulars, such as, for example, the number of ribs, often correctly observed, the position of the hands and the setting of the legs show that the eyes of Assyrian artists have been seen better from the very beginning than the Egyptian ones. In the Egyptian relief, it was customary for the profile setting of both legs to depict the one and the other from the inner side, that is, from the side of the thumb; in Assyrian relief, the foot closest to the viewer was always correctly depicted; in the same way, the hand closer to the viewer was reproduced along with its shoulder in an approximately correct core position, and sometimes, although not always, the other arm, removed from the viewer, as opposed to the Egyptian method, was completely obscured by the rib cage and remained in the figure only her hand and forearm are visible. Such animated poses and movements, which Egyptian art reported to the human body, have never been assyrian. But the images of wild animals in hunting scenes and horses in battle scenes are far superior to the Egyptian in terms of the transfer of both forms and movements. In the images located in the north-western palace, the background, as well as the surroundings, is only as much as is absolutely necessary for the plot to be clear. However, the river, presented in the form of perfectly regular wavy lines and animated by figures of fish and twisted spirals, is much more natural than the rivers in Egyptian paintings. The mountains are marked by a network of scales, which also constitutes a characteristic technique of Assyrian art; There is no shortage of trees, although they are depicted schematically, without distinction of individual species, and very coarse. Needless to say, there is no hint of any prospect. The following one after another elevations are drawn, as on the plan. Everything that stands or grows vertically is depicted, for the sake of clarity, as if reflected in a mirror, in a supine position, sometimes upside down. In general, the distribution of figures in space, just interrupted by a calm, simple alternation of objects, is made arbitrary and erratic. But at the same time, individual episodes are reproduced boldly and with the truth of life. Thus, there is a lack of not loyalty of sight, but the ability to convey the observed.

Fig. 175. Hunting for a lion. Nimrud relief. From the photo of Munsell

Fig. 176. Statue of Ashshurnasirpala. From the photo of Munsell

Remarkable is a wide strip of wedge-shaped inscriptions stretching along all four walls, always at an equal height, throughout the halls of the palace of Ashshurnasirpala, including halls adorned with images of large figures, where it passes through these latter across their torso. Explaining the content of images with stories about the king’s deeds, she does not make up the whole organically with the individual images she crosses, but nevertheless to a certain extent increases their decorative connection with each other.

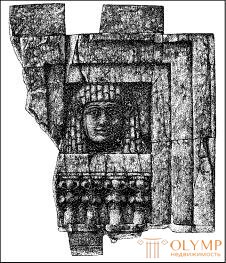

The state of round plastics in the times of Ashshurnasirpala gives us the concept of its sculpture smaller than life, the British Museum (Fig. 176). It goes without saying that it, like all Assyrian statues, has a strictly frontal position. The head with a long beard is not covered by anything. The body, designed to look at it only from the front, is very oblate. In the hands, arms and legs - the complete lack of realism; the clothing enveloping the whole body is divided into parts with a fringe sewn on it. The stele of Ashshurnasirpala, decorated with reliefs in the British Museum, is better compared to this sculpture compared to some of the more ancient Babylonian stelae. These stone, rounded on top monuments depicting the king, symbolic vicinities and extensive inscriptions constitute a feature of all Mesopotamian art; they liked to give the form of low, obtuse obelisks at the top, four faces of which were decorated with relief images of the king's hunting and combat exploits, one above the other. The obelisk of Ashshurnasirpala in the British Museum is mentioned less often than the obelisk of his son, just because only fragments of it remain from him. The existence already at that time of the connection between the Egyptian and Assyrian arts is proved by the heads carved in the Egyptian taste of ivory, kept in the British Museum, unless they originate from the later buildings; they were found in the northwestern palace of Nimrud and, apparently, were inserted into wooden doors or wooden panels (fig. 177).

Fig. 177. Carving on ivory. Fragment. From the photo of Munsell

The painting on the plaster in the upper parts of the walls of the palace of Ashshurnasirpala to some extent turned pale and faded after it was opened. According to Layard, they were elegant colored ornaments of bright red and blue tones. Figures are found in paintings only on glazed bricks: fragments of large paintings on a brick with such small figures are preserved that each brick contains entire figures. On a single fragment, which was undoubtedly found in the Nimrud north-western palace, all the figures without heads (Fig. 178, a). In contrast to the later images of this kind, we see here green draperies with white trimming surrounded by a black outline here on a yellow background. Ornamental motifs on the brick correspond to the decorations embroidered on the robes of the king and his nobles, especially luxurious and varied on the relief plates preserved in the north-western palace. All the ancient designs of the Assyrians, with its motifs taken from the animal and vegetable kingdoms, with its arrangement in rows and in heraldic style, are here before us in the most elegant design. However, the Egyptian lotus flower is still missing; Egyptian bronze vessels with ornamentation found in this palace got into it, obviously, only afterwards.

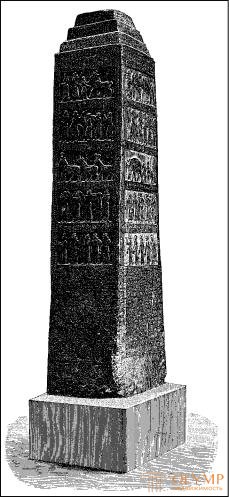

The son of Ashshurnasirpal, Salmanasar II (860-824 BC), built the central palace in Nimrud (Kalah) and expanded the buildings that had been begun under his father in Imgurbel (Balavat). The most important plastic works dating back to the time of the reign of this sovereign are in the British Museum; this is, firstly, the so-called black obelisk, on all four faces of which are placed in five rows, one after another, images of kings, tributaries of the Assyrian sovereign, with their elephants and camels (Fig. 179); secondly, the basalt found in Ashshur (Kalekh-Shergat), the king’s head lost in a sitting position and, third, most of the famous bronze plates that served as the facing of the gate in Balavat with images of the king’s marches. The style of these works has a softer, more vague contours and a slightly more distinct background in comparison with what we find in the north-western palace. The seated figure of the king gives the impression of a weak imitation of the same royal statue from Tello (cf. Fig. 156).

Fig. 178. Assyrian tiles with color images. By layard

Fig. 179. The black obelisk of Salmanasar II. From the photo of Munsell

In the central palace of Salmanasar II in Nimrud one of the most perfect examples of Assyrian painting on glazed brick was also found (see fig. 178, c). On the same brick are depicted the full-length king and the eunuch and the warrior accompanying him; the king holds a bowl in his right hand, from which he makes a libation in honor of the figure in front of him, which is only half preserved. The contours are still black, but barely noticeable. Faded paint costumes - white, dark yellow and grayish yellow; the background is light yellow. The figures are more slender than in the contemporary reliefs of this painting; in the arms and legs of the exaggerated muscles unnoticed. From the southeastern ruins of Kalah, probably belonging to the time of the reign of Rammaniraris III (811–732), numerous fragments of painting on brick were found, kept in the British Museum; they differ from the more ancient monuments of this kind by the white color of the contours (see fig. 178, b).

These outlines here delineated, without reference to the muscles, strikingly slender light yellow and light blue shapes on a greenish or yellowish background.

Tiglatpalasar III Usurper's Palace (745-727), in Kalah, was destroyed by his successor. Subsequently, Esarhaddon used the reliefs from the halls of this palace for his new construction. In all likelihood, they include images published by Layard (Mon. I, pp. 63-67), a procession with carved statues of gods carried by two people on their shoulders.

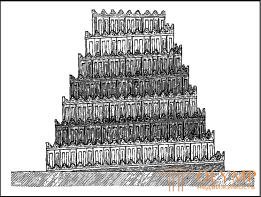

Fig. 180. Restoration of the Khorsabad temple. By Tom

Under the Sargonids, a new flowering of Assyrian art occurred. Immediately upon his accession to the throne of Babylon, the founder of this dynasty, Sargon (722-705), which began from 709 BC. e. being called Sargon II, he built himself in the area of present-day Horsabad, on the mountainside, the fortress of Dur-Sharrukin, on the western wall of which his proud, gigantic, crown-toothed palace stood. Perrot called Dur-Sharrukin the "Versaille of this Assyrian Louis XIV." On the palace terrace, to the south-west of the royal castle, next to it stood a temple, arranged in the form of ledges; probably it consisted originally of seven floors, successively decreasing with the approach upwards; only four of them survived. The outer surface of the walls of these massive floors was divided into parts with the deepened margins of a tilted profile and covered with plaster painted on the first floor in white, on the second in black, on the third in red, on the fourth again in white (

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)