Together with the history of mankind begins the history of art. Inscriptions on works of art belong to the most ancient written monuments, and for the history of art there is great happiness that the rulers of those ancient countries of the world in which writing existed, making extensive use of this new, precious for humanity invention, covered all sorts of monuments with various inscriptions in abundance. The oldest of these monuments of the history of mankind and his art are preserved on the banks of the Nile, the Euphrates and the Tigris, that is, in Egypt and Mesopotamia. These monuments, erected several thousand years BC. during the whole centuries they were completely oblivious, and although their existence was known, they were stubbornly silent about them until finally, in the XIX century, they didn’t draw general attention to themselves and one by one they became accessible to our understanding.

Where the most ancient monuments are preserved - whether on Chaldean soil, in Mesopotamia or on the banks of the Nile, in Egypt - this is a question still not completely resolved. The fact that the Chaldean art is more ancient is evidenced by the inscription made in the Berlin Museum, made by the Novo-Babylonian king Nabonid, who lived in 550 BC. e., and saying that there was an ancient king of Babylon Naramsin for 3200 years before Nabonid, that is, for 3750 years BC. e. This does not contradict the ethnographic studies of Brugsh and others, who have long attributed to the Egyptians Asian origin, although Erman and Maspero pointed to the mutual contradiction of these studies. Ratzel said (1894): "The cradle of Egyptian culture is Asia." Schweinfurt resolutely takes the side of Gommel (1897), in the footsteps of which young Assyriologists walk and go so far as to consider Egypt an ancient Babylonian colony founded in prehistoric times. But after B.F. Lehmann proved that Naramsin (as Winkler had said before) could not live 3750 years BC. e., again it seems likely assumption that the oldest found, at least until now, monuments belong to the Nile Valley. We can all the more remain with the opinion that in historical times both peoples, Egyptians and Chaldeans, undoubtedly related to each other, stood on the same level of cultural development and were completely independent.

Whether the related features of ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian artworks depend mainly on the origin of one art from another or are these traits due to the fact that from the very moment of the emergence of human art in general, these two arts developed simultaneously under the influence of completely identical local conditions - a question that we once again set, maybe later. At present, we confine ourselves to considering these common features as a sign of the same stage of development of these peoples - the stage that immediately follows the Bronze Age, the time when, in all likelihood, not only in the Ancient Kingdom, but also in the country of Ancient Egypt the first stone and bronze articles appeared and when the use of iron was not yet known there.

Opponents of the view that the climatic conditions of the area affect the art of the country cannot but agree that Egypt is an exception in this regard: one must be blind in order not to see the reflection of the nature of this country in works of art. Art and nature are here in the most lively correspondence. As far as the plant and animal kingdoms of the oasis formed by the spreading of the Nile River and the oasis spread in the desert, called Egypt, are peculiar, the intellectual outlook of its inhabitants was just as original. The original, confined in a close framework, the culture of Egypt for many centuries developed under the influence of natural conditions as consistently as no other, and if at present we know the art, customs and customs of the Egyptians better than the life and art of other nations closer to us in time and place, we owe it above all to the works of scholars and the excavations carried out in Egypt by such archaeologists as Champollion and Lepsius, Mariette and Maspero, de Morgan and Flinders Petrie, then to the study of hieroglyphs, thanks to which we have Champollion gradually got acquainted with the history of the Nile Valley on the inscriptions on the monuments, and, finally, the extensive print editions of these monuments. The former works of Champollion, Lepsius, Rossellini, Pris-d'Aven, and in particular the editions of Flanders Petri revealed to Europe the secrets of Egyptian art. Information about Egypt, we are largely obliged also to the properties of its soil, the constancy of its climate, customs and customs of its ancient inhabitants, based on centuries-old legends. The soil supplied the Egyptians with hard stone, the sun dried and made their wooden products and fabrics durable, and the religious beliefs of the Egyptians encouraged them to build temples for the gods and tombs to their great people so that these buildings would remain forever. God-like kings of Egypt thought to acquire immortality in heaven and earth, depicting their deeds on the indestructible walls of temples. The Egyptian priests taught that the afterlife of the deceased depends on the state of his body on earth after death, on whose image it took, and also on those sacrifices in the form of food and drinks that his shadow received (Ka) or which at least were depicted on the walls of his tomb by surviving relatives. From here came the embalming of the dead, whose mummies, including several thousand, have survived to this day, and laying them into strong stone or wooden sarcophagi, often inserted one into another, and the burial of the dead in deep mines, over which, if not naturally elevated rocks, stone monuments were erected and strong slabs were laid; hence the custom and tradition to place the statue of the dead man in a special section of the tomb, as well as the custom to depict various foods plastically or in a painted picture on the walls of the sacrificial peace, so that the deceased never needs food.

Almost exclusively, the temples and tombs of the ancient Egyptians owe us our acquaintance with the culture and art of their country. From the buildings in which the Egyptians lived and molded from Nile silt or were built from dried in the open air and only rarely from burnt bricks of a special kind and were covered with thin wooden paneling, only one foundation remained without the slightest trace of artisticity; stone buildings, such as temples and tombs, give us the opportunity to get acquainted with the essence of ancient Egyptian architecture.

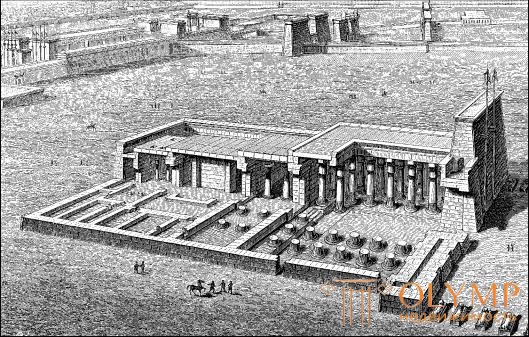

Egyptians mined small limestone for stone buildings in the Libyan desert, strong sandstone near Gebel Silsil in Upper Egypt, light red granite in the ancient quarries of Aswan (Siena), in the extreme south of the kingdom of the Pharaohs. In Egyptian architecture, we find a number of common features linking the various stages of its development. The vault was known to Egyptian architects for a very long time, if not from the deepest antiquity, as fake, that is, consisting of a series of stones protruding on top of each other, and real with a wedge-shaped keystone, but was usually used only in underground structures and structures of secondary importance. Monumental Egyptian buildings were covered mostly with a flat roof consisting of a series of stone beams supported on the walls, and in case of significant distance between these latter, on columns and pillars (Fig. 97). Covered galleries, surrounding the courtyards of temples on the inside, and halls with strikingly narrow gaps between the columns appeared, obviously, as a necessary consequence of the construction of the roof of stone beams. Undoubtedly, such a system of backwater was applied first in wooden buildings and only later moved to stone. It should not be forgotten, however, that already ancient dolmens, preserved in large numbers in northern Africa, indicate the existence in the original architecture of stone buildings of the roof, which lies on stone supports; To this it is necessary to add that the Egyptian buildings with a stone roof, in spite of their decorations, do not in the least resemble wooden constructions by their massiveness and heaviness. A characteristic feature of all Egyptian brick constructions - their walls upward significantly, though gradually, thin. This type of walls, borrowed, without any doubt, from wooden buildings and not belonging to limestone structures, is found in ancient times when building dams and fortresses of dense mass of Nile silt. The same hardened clay mass, we later see in the form of horizontal layers, laid in the walls of Egyptian buildings of brick and stone.

Fig. 97. Restoration of the Temple of Hona in Thebes (20th Dynasty). By Perrot and Shipie

Only the walls of polished granite were left uncovered; they didn’t touch even wall paintings. All other stone and brick walls were faced from top to bottom, inside and out, with a thin layer of plaster, and this layer was covered with multicolored plastic images, most of which are already phonetic hieroglyphs, which play, in terms of content, the role of writing; as works of art, they constitute the main part of the entire ornamentation of the building and, harmoniously merging with it, form one harmonious decorative whole.

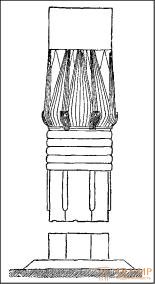

Columns in Egyptian stone buildings are strong enough to properly fulfill its purpose, that is, to serve as supports. But their decoration in a striking manner does not correspond to their purpose, often giving them the appearance of plants with long and thin trunks, the flowers of which, not yet unfolded or already blossoming, support the invisible abacus and form the capital of the column. Obviously, in order for the column to appear more solid, several trunks that make up the rod of the column were usually tied into bunches by strong hoops, and in the same place between them small stems of the same colors were passed as fastenings. In general, the ornamentation of the Egyptian columns of this kind gave the impression of something gloomy, although it was obvious that it had to express the contrast between the earthly life and the celestial life depicted on the ceiling of the building in the form of stars and birds. "The Egyptian," said Borchardt, "imagined his columns, imitating plants, freely ending and ornamented them according to this."

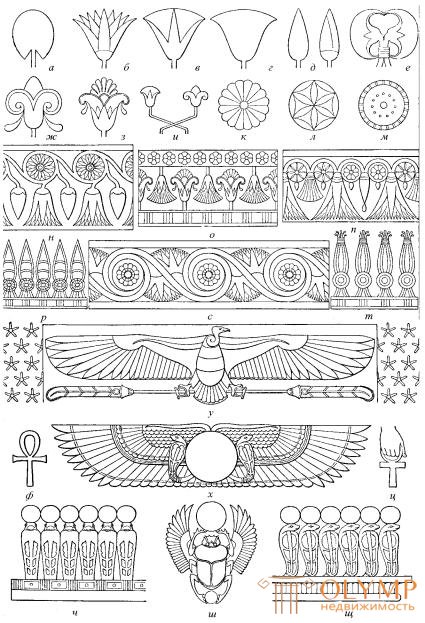

Fig. 98. Relief with lotus flowers in the tomb (6th dynasty). According to Priss d'Aveno

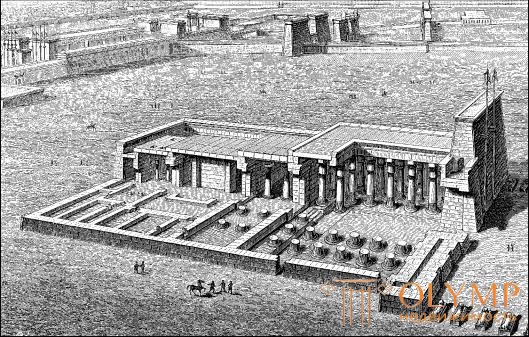

At all stages of the development of Egyptian ornamentation, consisting in the architecture of paintings and inscriptions, which completely covered the walls, plinths, cornices, ceilings, pillars and gates of buildings and preserved even in handicrafts strict purity of style, we find the same general features. Along with the geometrical form of the ornaments of ancient and primitive periods and with symbolic images of animals, mainly snakes (urey), we meet in Egyptian art in ancient times floral ornament. Therefore, the Egyptians can certainly be considered the creators of the ornamentation of this kind. Its same motive passed from generation to generation, from millennium to millennium. That this ornamentation was borrowed from the Egyptian flora is evident by itself (Fig. 98). The visible role is played in it by a lotus flower, not Indian Nymphaea nelumbo, as previously thought, but local, white or blue, Nymphaea lotus or Caerulea, as confirmed by Godfir, Riggle and Borchardt’s studies, and also prove that they characterize this plant (Fig. 99, a ) spatulate leaves, as well as the number and shape of the petals of those flowers, which are countless times on Egyptian monuments (d, e, c). In addition to the lotus in the imagination and in the ornamentation of the Egyptians, papyrus played an important role. If the plant, which in this picture is floating on the water, is a well-known lotus, then it is equally clear that the plant has long straight stems and fluffy ears, connected in bunches, which are shown in fig. 100 protrude from the water - papyrus bushes. The opinion expressed by Godfir, who was joined by Rigl and Perrot, that the "fan-shaped papyrus" of Egyptian ornamentation is none other than the stylized lotus flowers depicted from the side, was convincingly refuted by Borchardt. Even more incredible is the suggestion of researchers who believe that all forms of Egyptian ornamentation originated from one original form, and that the ornament in the form of an undisclosed flower cup (Fig. 99, f , f, f, and ) that Borchardt takes as a known modification of the lotus flower per line, and Schweinfurt for aloe, and which is usually called the Egyptian palmette when provided with an appendage in the form of a cone or a fan-shaped crown. But the most unbelievable, no doubt, is the view that the Egyptian rosette also represents, if you look at it from above, nothing more than a lotus flower, according to Godfir, which has not yet blossomed, in the opinion of Riggl, has already flourished. That this outlet can easily be mistaken for a flower is beyond doubt (fig. 99, k ), but in any case it resembles rather an aster flower, a daisy flower, a daisy flower than a lotus flower. Sometimes it is quite clear that it represents only the further development of the four-leaf ornament (Fig. 99, l ); it is often possible to take it as a star (fig. 99, m ), in which case it points to the most ancient ornamental motifs, apparently depicting the sun, moon and stars in the form of concentric circles, sometimes bordered with small circles. How in the combination of the above elements of ornament with the help of various changes, additions and combinations, luxurious and highly artistic bands of the ornament were formed in conjunction with a wavy spiral, the figures of n - c show. Egyptian ornamentation was not alien to the simplest wreaths of leaves, vines and clusters, palm trees and other plants. Ornament in the form of a bundle of stems, fastened at the bottom with a rosette and sometimes similar to a row of copies with cusps protruding upward, in Borchardt's opinion, imitates the fringe of a carpet.

Fig. 99. Ancient Egyptian ornaments. Drawings by Max Kunert

Fig. 100. Relief with papyrus in the tomb (4th dynasty). According to Priss d'Aveno

The flowering plants, which, as mentioned above, form either alone or in the form of bundles of columns, towering on bases that have the form of small earthen heaps, are Nymphaea lotus and Numphaea caerulea, papyrus, palm tree, some species of bluebells and reeds. The history of the development of these architectural forms is extremely clearly outlined by Borchardt. The most common columns are lotus and papyrus. The former, having capitals in the form of an unopened or blooming flower, often lack the foundation, which is almost never observed in papyroid columns, the capitals of which represent a closed or open aggregate of ears. The individual stalks of the beam in lotus-shaped columns are circular in cross-section, and in the papyrus-shaped columns - triangular in shape. The rods of the columns of the first kind have neither leaves at the base, nor a thickening, whereas the rods of papyrus columns are narrowed at the bottom and are wrapped in leaves. In the lotus-shaped columns, the petals of the calyx of the flower, which plays the role of capitals, reach to its very top, and in the papyrus-shaped columns they are much shorter and border only the lower part of the capitals. In fig. 101 - a column in the form of papyrus, and in fig. 102 - in the form of a lotus, and the cups in both are closed.

Fig. 101. Papyrus column from Karnak. By Perrot and Shipie

It is not unbelievable that many of the ornaments borrowed from the plant kingdom found a place in Egyptian art only because they had long been given a symbolic meaning, as can be seen especially about the lotus flower, which was obviously personified by the sun. Other ornamental motifs in Egyptian art are also symbolic. If this cannot be said with complete confidence about an ornament depicting a dark blue sky with stars, which we constantly see on the ceilings of Egyptian tombs and temples, as well as images of kites flying with outstretched wings (Fig. 99, y ), undoubtedly, solar circles, and the winged disk of the sun over the entrances to the temples (x), and the sacred snakes, urey (x and u), and the cross, with a ring or loop above, serving as a symbol of eternity (f, c), скарабея – блестящего египетского жука (Ateuchus sacer, ш), который, олицетворяя с the battle of earthly life and the future life of a person, is often both as decoration and as an independent artistic work.

It is necessary to distinguish between two types of Egyptian plastics: sculpture and flat images that obey the same laws of style, regardless of whether they are painting or embossed work.

Material for sculptureThe Egyptians served stone, wood, ivory, bronze, and clay. Numerous colossal statues were made of granite, basalt or diorite; life-size statues of sandstone or limestone; the smaller ones are made of wood or bronze. Clay figures were always small. Statues of sandstone and limestone were usually covered with a layer of paint, while statues of solid colored stone were painted only occasionally or only in some of their parts. The most important monuments of Egyptian sculpture are statues of gods and people; There are also animal figures. Sculptures of people were placed in tombs and temples. In the first, besides a few statues representing the deceased in various forms, the images of his servants were also placed. Statues of kings, builders and founders of these buildings were placed in front of the temples and inside them;Often these statues also represented the same person in several forms.

Fig. 102. Lotus column. By borchardt

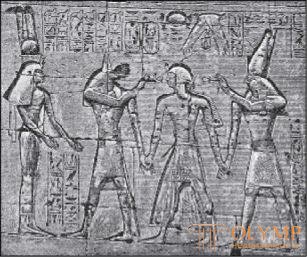

Images of gods in Egyptian sculpture play a minor role. Hiding in gloomy sanctuaries, where only Pharaoh and the priests were allowed, the figures of the gods, if they had a human appearance, were depicted in the Nile boat. In other parts of the temple, the sculptures of deities were not objects of worship, but votive offerings. Although the deities, the patrons of certain regions and cities of Egypt, which had a purely earthly character (the remnant of ancient fetishism), later often merged with the bright gods of the priestly religion, these deities, despite the heavenly light that lit them, could not cast off the earthly shell . Egyptian people almost always imagined gods in the images of sacred animals. Amun, the ancient god of the city of Thebes, even in times of Roman rule, turned into Jupiter-Amun, retained his ram horns. Adoration of his double, the ancient god of the sun Ra, arose from deification of the falcon. Pta, the ancient god of the artists of Memphis, was honored in the form of the sacred bull Apis; Gator, the goddess of heaven and love, in the form of a cow; Sobk, the local deity of Fayum, in the form of a crocodile; Gorus, the sun god, is in the form of a falcon; Bast, the goddess of Bubastis, in the form of a cat; The god of wisdom is in the form of an ibis or a baboon; Anubis, the god of death - in the form of a jackal (Fig. 103). The animal element is less noticeable in the images of Neyfa, the all-seeing goddess Sais, but especially in the images of Osiris, the great god of the dead, whose cult was a continuation of the cult of the ancient deity, the patron saint of Abydos and his consort Isis, "the wisest of all men and gods." Egyptian sculptors in most cases were limited to attaching sacred animals' heads to divine statues. At the same time, it goes without saying that the images of gods were not only not given to ennobled human features, but also created new creatures. Far less often did the Egyptians make such statues of demi-polupreyrey, in which a human head is attached to the body of the animal. The main specimens of such sculptures are sphinxes with the body of a lion and the head of a person, personifying the divine origin of royal power; This sculptural image was so common in the ancient era and in subsequent times that it is not only repeated countless times in Egyptian art, but to this day remains the province of artistic creation. Among the images of the dual nature of the purely animal kingdom belong the vulture - the winged lion with the head of an eagle, which has, undoubtedly, Asian origin, and the image of a lioness with the head of a falcon - the creation of a pure Egyptian fantasy. Finally, an example of human winged images can serve as a statue of Isis and Nephthys, who played a certain role in Egyptian art of a later time.

Fig. 103. Relief of the Temple of Abydos (Horus and Anubis). By Maspero

Of course, the Egyptian sculptors knew better the structure of the human body and reproduced it more correctly than the artists of the peoples mentioned above. The hot climate of Egypt, forcing to wear only the lightest clothes, contributed to the study of the naked body. The best of the ancient Egyptian images of a person in a standing or sitting position almost leave nothing to be desired, if at all to demand from the sculpture the transfer of a nude body frozen in stillness. Such a conditional reproduction of human figures can be explained by the initial stage of the development of art, above which no people rose to the Greeks, only at the beginning of the 5th century. BC e. gone further along the path of artistic creation. Using the example of Egyptian sculpture, he founded his theory of frontalism in plastic of ancient and primitive peoples in general, as well as cultural peoples who stood on the same level of development with the peoples of the ancient East.

In Egyptian plastics, we encounter exceptions to this rule only when animals and crude human figures are depicted, as, for example, in one image of the lower dwarf-shaped deity Bes, the Berlin Museum. The question of whether Egyptian sculptors have developed laws that determine the comparative size of individual parts of the human body, whether they had a canon for this is controversial. Diodorus said (I, 98): "They divided the length of the whole body into 211/4 parts and, accordingly, determined the mutual correlation of the rest." Some of the first Egyptologists of the nineteenth century took the length of a foot as the unit of this Egyptian canon, the others — the length of one of the fingers; the newest researchers undoubtedly reject the existence of the canon in Egyptian sculptural images of people. In extreme cases, the rules of proportionality of the parts in the statues could exist only in the era of the Ptolemies and Roman rule. Nevertheless, in Egyptian sculpture there were laws linking the freedom of movement and the postures of human figures, which required them to have a fixed, frontal position. So, with the exception of kneeling figures, the legs of the statue always rest on the ground with the entire foot. Only in male standing figures one leg, left, slightly pushed forward; in the same female and child statues, both legs are always on the same line. Hands with clenched fists sometimes fit snugly to the body, but more often the position of the hands, maintaining its angularity and convention, already obeys the known laws of symmetry, and, finally, occasionally, as is observed in ancient Haldean statues, the hands rest on the chest. Along with the figures in the standing position are often found figures sitting on the throne; images of people squatting, kneeling, sitting on the ground with legs tucked under themselves, according to Eastern custom, are also often caught. Heads in all Egyptian statues testify to the existence in Egypt, thanks to the hot climate, the custom of shaving hair and beard; only in rare cases, mainly during festive ceremonies, was a wig or a bandage put on his head, and a fake beard was tied to his chin, and its strings were often visible.

In Egyptian sculpture there are also entire groups of human figures, and it is precisely in them that the law of frontality is manifested especially strongly. If a figure was depicted on a throne with a child in her arms, the latter, facing directly to the viewer, made a right angle with the main figure. If the group consisted of two or three figures, then they were always depicted stretched out in a single line, when viewed from the front (Fig. 104). At the same time, the main figure was twice or three times larger than the rest, especially when the latter represented his wife or children.

The rule that such a person - in most cases, the king - was depicted as a giant in comparison with the surrounding figures, was also observed in Egyptian images on a plane. This method of designating the spiritual superiority of one person over others by increasing the size of his figure should be recognized as quite natural at a certain stage in the development of art.

Fig. 104. Pta-Mai Group. From the photo

Egyptian images on the plane in their historical development were also subject to well-known general laws. Despite the few recent improvements brought about by the desire for freedom, these images constantly retained their silhouette character. The transition from painting on a plane is also almost imperceptible, which, however, due to sharp definiteness of the contours, looked more like painted reliefs than like real paintings, to images with slightly deeper contours, and from these latter to coylenglyphs or hollow reliefs (reliefs en creux) whose outlines are so deep that it was possible to model the depicted figures and objects without touching the background (see Fig. 103), and, finally, to real bas-reliefs, that is, images slightly protruding on the hollowed background. In any case, the Egyptians themselves, as Erman remarked, did not see a significant difference between painting, sunken reliefs and bas-reliefs; and at present it is hardly possible to say with complete certainty about many monuments, what were the main motives that prompted artists to choose one or the other of these kinds of technology.

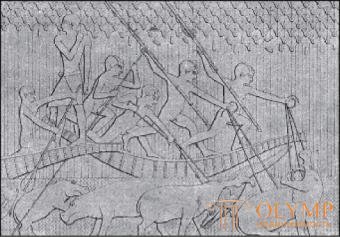

The examples of these various techniques of art are mainly monumental images on the inner walls of the tombs, the inner and outer walls of the temples, drawings on papyrus scrolls - the oldest of miniatures and illustrations, finally, images on sarcophagi, vessels and various utensils. The content of relief painting and plastics brought the life of the depicted persons in its entirety: there were religious ceremonies of various kinds, and large historical paintings glorifying the acts of the Egyptian kings, and scenes of rural, craft, shopping and home life, to which the landscape was often joined as well as idyllic paintings; but upon closer examination, it turns out that all these reproductions of life in its various manifestations had one goal, namely, they had to glorify the deceased on earth and provide him services in the afterlife. Genre paintings in the background of the landscape, as well as scenes of rural and hunting life, play the same role as the image of foodstuffs necessary for the shadow of the deceased. In the idyllic paintings we find, again, the same idea as in the image of different foods and drinks.

The laws of the style of Egyptian painting and plastics were determined partly by the famous requirements of custom, partly by the imperfections of technology. And here we see that the ability to depict various phenomena of life on a plane is younger than the art of correctly reproducing individual human figures in all their volume. But technical incompetence in most cases is covered by the conditional rules of decency, thus serving virtues by virtue of necessity. If you look closer to the individual figures, it turns out that throughout the entire existence of Egyptian art, the rule to depict faces in profile prevailed. Together with the further history of the development of art, we will get acquainted with its more advanced models, representing exceptions to this rule. But the profile image of the figures was only partly possible for Egyptian artists, which depended on their desire to express everything accurately and clearly. Head, arms and legs were given in profile, shoulders and eyes visible from the front. Between the upper part of the chest, represented by en face, and the legs depicted in profile, there was the middle of the body, part of which was drawn in a straight position, and part at the side. The hands are striking in their unnaturalness: the first four fingers are always the same length; palms and upper arms are often alone in the place of others; but even more strikingly, complete neglect of the correct position of the legs. In Egyptian art, at all stages of its development, the rule to depict the legs in profile, standing one next to the other, and, moreover, from the inside, was observed, so that only one thumb could be seen closing all the others. But at all times there were, according to the pictures, single exceptions to this general rule; for example, the foot closest to the viewer sometimes maintained a natural position in which all five fingers are visible. This happened when the artist suddenly had the idea of reckoning with reality. However, the monuments known to the author of this work in the originals or copies, do not indicate the existence of such exceptions in the ancient period of Egyptian art. In the epoch of the New Kingdom, the correct positioning of the legs is quite often and is observed more noticeably, although it still does not constitute a general rule. Hands do not have an organic connection with the body, and their movements are usually unnatural and angular. If it was necessary to present any member of the body, an arm or a leg, stretched out, the ancient Egyptians constantly depicted the stretched arm or leg that is more distant from the viewer. If the Egyptian artists did not have any reasons that prompted them to depict the figure looking to the left, they always turned their faces to the right. Both of these rules were discovered by Erman. For our part, we note that, in view of the many exceptions, these rules cease to be so. But Erman is right, as far as the image of high-ranking persons is concerned, to which this usual, consecrated by tradition, primitive artistic technique was constantly applied.

This silhouette style, exemplified by, perhaps, the real painting of silhouettes, is such that its imperfection is expressed in groups stronger than in the images of individuals. The difficulty was inevitable to occur when the image of two figures standing side by side. According to the rules, it was necessary to depict one figure above another, so that the feet of the one farther from the viewer would fall over the head of the front figure and be of the same size as it. Often, and in ancient times constantly, the upper rows were separated from the lower ones by lines that signified different planes (front, middle and rear) in the form of stripes. Often also, especially in later times, when mass movements were plastically depicted, the rear figures protruded by half because of the heads of the front figures, and often the image of the figures standing nearby, due to the doubling of the contours, approached the present perspective image, and, of course, the previous error repeated Perspective - increase in the size of the rear figures

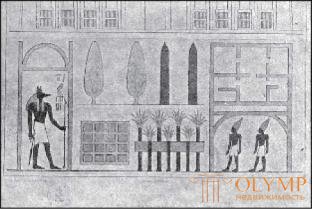

As far as the Egyptian artists were from understanding the laws of perspective in their images on a plane, this is evidenced above all by their way of depicting the landscape surrounding objects. The author of this book already had a case earlier, on another occasion, to find out in detail that landscape played a prominent role in the meaning of the background in many figured images of Ancient Egypt, but was never an independent branch of art in it; representing the background, at best, he transmitted only a few parts of inanimate nature, marking them as on a geographical map: reproduced many well-captured details, but never imagined a complete and, moreover, promising whole. For example, a quadrangular pool of water surrounded by trees, depicted in the funeral chambers in Add-el-Qurnah, has the appearance of a drawing representing a regular square, and its water, according to custom that has existed since time immemorial in Egypt, is indicated by a series of zigzag lines drawn perpendicularly along blue field; 24 trees surrounding the pool from all sides, although they are depicted at the edges of the picture exactly on the places where they should be, with their tops facing all four sides. The image of the sacred garden in the tomb of Eleifia from the time of the 17th dynasty represents a drawing shift with a perspective view (fig. 105).

Fig. 105. The sacred garden in the tomb of Eleifia. By Perrot and Shipie

About the reproduction of atmospheric phenomena in Egyptian images on the plane, of course, there can be no question. In Egyptian art, we find no signs of either the correct transmission of light and shadow, nor the correct distribution and combination of colorful tones. Each paint was superimposed on the space intended for it, without mixing with others. Colors found in nature were transmitted only approximately. Egyptian men and horses were depicted as reddish-brown; Asian men and Egyptian women yellow. The motley costumes of the foreigners (the Egyptians themselves preferred to wear clothes made from completely white linen fabric) were reproduced with all the variety of their colors. Many images of the gods were luxuriously illuminated with yellow, red, green or blue colors, representing, in this way, a whole symbolism of colorings, which, however, is not available to our understanding. Finally, it is remarkable that Egyptian art, at all stages of its development, from the very epoch of its inception, turned out to be completely powerless when it was necessary to express mental movements in facial expressions; it portrayed moral unrest with the help of body movements, and the faces had the same expression, resembling a forced smile.

The gradual development of all Egyptian art followed slowly the general course of human culture. The great coups d'état caused from time to time flashes of artistic creativity, gave rise to new ideas and new images; but even after the radical transformations he tested, this art remained frozen for centuries in the former close framework; in the slow course of artistic creativity of the Egyptians, chained to the heavy chains of ancient traditions, who took away lotus and papyrus in such an important place, we never and never find signs of the individuality of this or that artist whose name would be associated with new steps in the field of art.Of course, in the history of Egypt there is no shortage of artist names. We find there as a ch

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)