When we talk about China, we come to the idea first of all the Great Wall of China, Chinese braids, porcelain, the famous Nanking Porcelain Tower, and in our imagination is the idea of the most populated, most ancient, most stable and most self-contained state the globe. However, upon closer inspection, some of these concepts are in a slightly different light. The Great Wall of China, built 2200 years ago along the former northern border of the empire, did not delay the conquest of China by the Tatars, against the invasion of which was erected. The Chinese braid, first imposed on the sons of the Heavenly Empire by the last Tatar conquest of China (in 1640 AD), exists only since the last accession of the 22 great dynasties of the Chinese emperors of the Tatar dynasty Manju. Nanjing Porcelain Tower, erected at the beginning of the XV century AD. e., destroyed in 1853, which was really a miracle of art in its lining with shiny porcelain plates 65 meters high and consisting of nine floors with roofs with bells around the corners, experienced a common fate with almost all buildings of Chinese architecture to exist for only a few centuries . Opinion about the immutability of Chinese culture and its closeness for all foreign influences does not hold water. In the history of Chinese art, it is irrefutably proved that it was subjected to these influences. Fr Geert devoted even a special essay to this question. Although Geert considers it unproven that the ancient West Asian forms influenced ancient Chinese art in the millennia that preceded the Christian era, however, there are indications of this, and since the last century BC. e. in Chinese art, one after another influenced Western Asian, Greek, modern European, sometimes even reviving and modifying it, and it, for its part, was the root of all East Asian art.

The history of Chinese art from ancient times was described in detail by Chinese writers. Fr Geert dedicated a special essay to this literature. Back in the ninth century n. e. Chang Yen Yuan wrote the history of Chinese painting before his time - a great work, which is an important source of our knowledge on this subject. From the next century, descriptions of museums with many illustrations, art collections and textbooks have come down to us. However, the artistic and historical material contained in these works was, until now, known to us only very fragmentary.

At the end of the XIX century. Europe's familiarity with Chinese art was mainly based on the writings and writings of French missionaries in Beijing, such French experts as Pottier, Stanislaus Julien and Du Sartel, such English researchers as Sir William Chambers and William Anderson, and such German scientists as Baron Ferd. von Richthofen. After Paleologue, in 1887, published the first coherent essay on this story, the study of it made rapid progress, especially due to the fact that it was undertaken by researchers armed with a thorough knowledge of Chinese. The names Ed are closely associated with these successes. Chavannah in France and Fr. Geert in Germany. In a number of monographs, Geert pointed out to Europe a completely new basis for the history of Chinese art, and the exhibition of works of Chinese painting collected by Geert, arranged in Dresden in 1897, was very interesting.

The credible history of the "Middle Empire" begins with the Zhou dynasty (1122-255 BC). Nevertheless, historians of Chinese art carry some of the surviving works of art in China, especially vessels, to the era of the Shang dynasty (1766-1122 BC). The period of independent national development of Chinese art lasts until the Han dynasty (206 BC - 221 AD), although signs of Babylonian-Assyrian influence are noted in the architecture of the earlier era. Around 115 BC. e. Influence on Chinese art begins from the West Asian, Greco-Bactrian, and from 67 AD e. Indo-Buddhist art began to spread slowly in China. However, Chinese art again absorbed and overcame all foreign influences. Its major creations, modern to our Middle Ages and the Renaissance, bear on themselves quite a national imprint.

According to its main features, Chinese art, as opposed to Indian art, cannot be called either monumental or fantastic; most likely, the name "art of small items" and "reasonable" came to him. Saying this, we do not deny that Chinese art in its time showed a desire for monumentality of sizes and fantastic forms, but we want to say that its preserved monuments, as well as those that are known to us only from their surviving Chinese images, undoubtedly above all, works of so-called small art, the charm of which lies in the peculiar sense of nature, in the subtle understanding of the requirements of decorativeness and in part of the refined, partly naive taste, which often surprises us delight. The most monumental of the works created by Chinese hands, still remains the Great Wall, stretching hundreds of miles, with its huge quadrangular towers and majestic gates in the form of circular arches. The most fantastic works of Chinese art should probably recognize some of the ancient examples of painting on silk or on paper, although these works emit more dreams of sensuality and sleepy dreams about nature than the power of fiery imagination.

Chinese architecture lacks monumental grandeur and strength; this is manifested not only in the lightness of the materials used by it, wood and brick, which, like the Polynesian primitive tribes (see Fig. 57 and 59), are replaced by large stone blocks only when building massive terraces and concessive foundations, but also in small scale all architectural forms; even in temples and imperial palaces, an increase in premises is achieved by arranging many small separate buildings and placing them next to each other, in one common fence. Freedom of artistic creativity is impossible for Chinese architects because of the shy and ridiculous government regulations that define for each house one or another number of columns, according to the rank of its owner, establish an exact digital relationship between all parts of the building and provide some space to the builder’s whim except in parts of the building hidden from the eyes of a passerby.

Chinese architecture resorts to the vaults except for laying the foundations only when building gates and bridges; but in this case too, the false vault, formed by protrusions of mutually opposite walls (see fig. 150), is often used instead of the present vault with a capstone. Domes this architecture does not recognize completely. The wooden rafters of the roof of all the buildings, which remain unmasked from the inside, and sometimes covered with a ceiling with cassettes, support the tiled roof, which is very prominently above the walls and along the edges, curved upwards; The rafters rest on the wooden frame of the walls, which consists of frames, the shape of which in the main parts is determined, of course, by the building laws, but in some parts it mimics the lattice work that has arisen from the wickerwork. The wall in between these frames bears only its own weight. According to Semper, it "essentially is nothing more than a Spanish wall that looks like a carpet made of brick," which, all the more, does not matter of the part of the structure that plays the role of a support or carries a weight, so that everywhere mobile, stretched between forests, completely independent of the roof load. " Therefore, the pillars in the frame that serves as the pillar of the roof, usually round, mostly wooden, and only marble in the imperial palaces, are placed now in front of the wall, now behind it, then in it itself. In the first case, they form a veranda in front of the building, in the second - they are not visible from the outside, in the third - they protrude from the wall in the form of semi-columns. Their bases, as a rule, consist of simple round pillows, and the role of capitals often play, as in India, spacers in the form of consoles, and they are sometimes given the shape of a dragon, personifying the Chinese sky and the power of the Chinese emperor, or any other symbolic fabulous animals. In general, the lattice, according to Semper, constitutes the main element of Chinese architectural ornamentation: we find it in the form of a thin bamboo braid in the lining of the lower part of the interior walls, in the form of a frequent lattice of an elegantly changing pattern, sometimes geometric with a lot of decorations, in the outer fence of garden pavilions (Fig 579, a ) and other airy houses, in architectonic wooden handicrafts, alternating with pillars and crossbeams, especially in the railing, connecting the light upper part of the building with its massive foundation.

Fig. 579. Chinese architecture: a - Chinese garden pavilion; b - Temple of Heaven in Canton. From the photo

These buildings, which develop mainly in a horizontal direction, produce an artistic impression mainly with their roof, which protrudes forward over the surface of the walls and bends upward along its lower edges. Such roofs, usually with slopes and only in rare, exceptional cases with tongs, have a ribbed appearance due to the fact that they consist of concave tiles covering each other, sometimes equipped with terracotta figures of snakes, dragons and other animals, with their trellis backwater from the bars of intricate carving, edged with dragon's teeth, crowned with temples, huts, towers and gates, and in the absence of beams even simple fences. One of the main features of Chinese architecture is that such a roof is double or even triple for effect, one above the other, so that the building has several tiers of roofs (b). Famous towers dominating Chinese cities and villages rise to 9 or even 15 floors, each of which is separated from the protruding roof following it, and the steep lines of such buildings are hidden to such an extent by these sheds that it seems as if they were built on top of each other. not real floors, but only roofs hung with bells at the edges. The assumption, which was often expressed, that the shape of the Chinese roof is an imitation of the shape of the Tatar tent, was refuted by Ferguson, who pointed out that the prevailing shape of these tents is conical. This researcher is more likely to see in the form of a Chinese roof the adaptation of the Chinese taste to a practical goal, protection from rain and sunlight. In the overall impression of all Chinese buildings, the tallest and the lowest, the bright coloring of the entire building plays an important role, with the exception of the massive stone foundation. The brick walls of the buildings are lined with plaster, their wooden parts are painted with variegated colors and sometimes lacquered from top to bottom; but the yellow glazed tile on the roofs, apparently, constitutes the exclusive belonging of temples and imperial palaces.

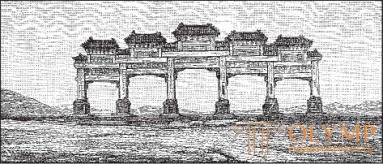

Fig. 580. Chinese honorary gate; the five-span gate at the entrance to the tombs of the Ming Dynasty. According to Paleolog

Of the stone buildings, in addition to the walls and their gates in China, so-called honorary gates are worth mentioning - separate buildings, which, as a rule, were erected on the streets and squares according to the highest or highest order in memory of important events and great people (Fig. 580). These "pa-lu" are of the same origin with stone gates in the fences of Indian stupas and with wooden "tories" in the fences of Japanese temples. Although they are stone, but their style is as if they were a wooden structure; however, only in rare cases when their spans, in the amount of from three to five, have not a straight line shape, but represent circular arches at the top, the main element of stone architecture is also introduced into their style. The Chinese roofs that replace them give them a completely national character.

The monumental decorations that we encounter in Chinese sculpture do not give us a sufficient idea of the monumental sculpture of the Chinese. Stone planks with relief images from the history of the Han dynasties, studied by Ed. Chavanne, apparently a single phenomenon of its kind; As for the large statues of people and animals, placed on some roads, they give the impression of small sculptures, reproduced on a large scale. We should not forget that in most Chinese buildings with stone walls there is not even room for large works of sculpture. There are no idols in the temples of the ancient Chinese cult of heaven. In the ancestral chambers in the Chinese houses, statues and busts are replaced with boards with inscriptions. The revulsion of the Chinese from the image of the naked human body, for its part, impeded the development of the style of higher sculpture. However, the Chinese are endowed with subtle observation, and through diligent and prolonged exercise, the hand of the Chinese accurately reproduces what his eye sees. The history of art finds Chinese sculpture almost free from the rule of frontality. The best of the Chinese artists already knew how to properly see the dressed body in various twists and reproduce the heads and hands with great naturalness and expressiveness; the ideal types appeared to them only as imitations of Indian patterns, which, in turn, arose under Greco-Roman influence. The national sculpture of China transmitted Chinese heads with all their distinctive features - oblique eye placement, prominent cheekbones, flat noses; at the same time, she rather humorously exaggerated her individual characteristics, rather than softening the racial characteristics, which, obviously, did not at all seem repulsive to artists.

Thus, the best that Chinese plastic only made are small items, and with the help of some of them we can get acquainted with it in European collections. Images of animals, people and gods in a small form, the Chinese have always cast in bronze; Bronze figures are found partly as independent works of art, partly as ornaments of vessels. The Chinese have long been extremely adept also in wood and ivory carvings, showing the greatest patience in this matter. Along with independent small plastic works, we find in them a particularly rich sculpture of reliefs on boxes, caskets and all sorts of objects; The through relief, in which the figures are drawn not on a solid background, but freely, so to speak in the air, constitutes Asian specificity, a favorite decoration of these objects. On the other hand, the hard greenish jade (iadite) for a long time was the Chinese favorite material from which they made not only liturgical bowls and cups, but also all kinds of buttons and plates for jewelry, and before the invention of faience - also cups and saucers. At the same time, more solid types of stone, such as, for example, rock crystal, onyx, chalcedony, sardonyx, whose multi-colored brilliant layers served to cut out figures of animals and plants, had the same usage. Later, along with this kind of work, carving from a wen flourished on a small scale (Fig. 581). Finally, the manufacture of all these things took possession of ceramics, especially the modeling of porcelain, which is a light and solid mass; and although the main role in the ornamentation of porcelain vases was played by painting, however, there was no shortage of reasons for the modeling of this primitive plastic material. In conclusion, this was joined by the famous Chinese varnishing, for the most exquisite works of which served as samples of Japanese products. Plastic lacquered works are very different from the paintings. Lacquer layers are stacked on top of one another until it is possible to cut reliefs from them or to round out the outlined forms. In all the small works of Chinese plastics, we are seduced by common sense, with which forms are adapted to the purpose of the subject, a great love for the depiction of the details of animal and plant life, the sense of nature that is attached to earth and sky, a lively, though sometimes somewhat external, understanding of the subtle play of colors. The dignity of the best Chinese works in all these branches of art can not be judged on the basis of those dozens of items that are currently flooding the European markets. In contrast to the Japanese, the Chinese almost never sold their best works to foreign lands.

The greatest independence was shown by Chinese artists in painting, encompassing all types of modern European painting.The history of Chinese painting, according to Fr. Geert, is already sharply delimited department of world history of art. Of course, it seems to be primarily a history of artists, but among the best works of the best Chinese painters, very few have survived or come to Europe. However, we have become available undoubted copies of famous Chinese paintings, and with their help it is possible to make an overview of the progress of Chinese painting.

Fig. 581. God of longevity. Chinese Wen Statue. From the original

About the wall painting of the Chinese can be said only a little. The aforementioned Chang Yen Yuan, who lived in the ninth century, reports amazing things about the magnificent paintings on the walls of temples and monasteries in the ancient main cities of the empire. The outer surface of the screens in front of the gates of Chinese houses and parts of both the inner and outer surfaces of the walls of these houses are now often decorated with paintings made with water-based or glue paints directly on the plaster. However, the aforementioned more ancient paintings were probably mobile wall decorations, and there is hardly a significant difference in terms of style between the newest light wall paintings, real independent paintings, and those pictorial decorations with which the Chinese cover all the objects of so-called small art. Of the individual paintings, images filled with water-based colors on pieces of silk fabrics and paper sheets or on long strips of silk fabric and paper deserve special attention. Such paintings, fitted with rails above and below, are hung on the walls like our oil paintings; the first and the last have hard covers, like book covers, and fold up like an accordion, so you can open them, look at them and then close them like books. In these paintings, convolutions, books with paintings or paintings on separate sheets, clearly reflects the history of Chinese painting. Everywhere in them we see the same character of this painting, in many respects similar to the illustrations in the manuscripts; everywhere we notice the same prevalence of contour drawing, which is felt even where the contour lines, as in the works of the newest impressionists, are almost completely blurred; everywhere in complex compositions we find a high horizon, due mostly to the high aspect ratio, shallow perspective depth and even less familiarity with the laws of perspective. Many paintings of famous Chinese masters are nothing more than black outlined drawings drawn with ink, in which the outlines follow the established rules of calligraphy, consisting in special strokes and brush strokes. These calligraphic rules, according to Anderson, still need to add 10 different conditional schemes, with accuracy followed by each artist. Then in Chinese paintings we find a translucent, mostly light background and everywhere the same thin and flat overlay of light colors, deliberate neglect of shadows that the Chinese view as dirty spots, ignorance of the effect of light and shade and insufficient roundness in the modeling of individual figures. The weakening of the brightness of colors away is better than linear perspective. To show the distance between the individual "scenes" of the landscape, layers of clouds and fog are inserted between them, rather thick and often strangely twisted or stiff; atmospheric moods, despite the graphic character of Chinese painting, are often expressed in it not badly.

With regard to the human body, the Chinese from ancient times, to which only we are able to trace their paintings, tried to depict it from all sides, in all sorts of positions, in all angles, as far as possible. In contrast to the landscape in this kind of images, the Chinese, for thousands of years before our time, achieved such freedom and sincerity of creative work that European artists acquired or regained for themselves only a few centuries ago. The lack of ability of the Chinese to depict large and complex compositions encouraged them to prefer small groups or snatch individual objects from nature and treat them as independent subjects. Thus, individual trees in their lush spring attire or in winter snow clothes began to take place in the foreground, blooming branches with birds and butterflies sitting on them, bamboo cane in which sparrows fluttered, bridges thrown over waterfalls, and so on. One cannot forget, however, that Chinese painting with its style of flat images, similar to the one we saw - of course, in a different form - in Greece, even in Polygnotian painting, was subject to a special kind of strict style laws.

Finally, we must recall that the Chinese long before the Europeans invented typography with the help of boards, and at the same time printing pictures. It is believed that the art of printing monochrome black prints engraved on wood originated in China at the end of the 6th century AD. e. as an integral part of typography from boards, the transition of which to printing by typesetting letters we do not undertake to trace here. But in the XVII century. The printing of polychrome woodcuts by means of several boards, rubbed with various colors, was already in a flourishing state, from which it can be concluded that this art developed before the designated time. With the graphic character of all Chinese planar images, the style of chromaloxylography in China is subject to the same laws as painting.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)