Although the art of the Chaldeans and the art of the Egyptians in historical times developed independently of one another, there is no shortage of features in them indicating their original relationship, which is noticeable in all conditions of life of both peoples.

The rivers of Mesopotamia, like the Nile, are periodically prone to flooding from the spring thawing of snow on the mountains of Armenia, on the Nile - from the summer showers of tropical Africa; both here and there, floods from ancient times are regulated and moderated by canals and contribute to lowland fertility, the puffy soil of which not only favored farming and cattle breeding, but also prompted brick making and buildings made of it. Lower Mesopotamia lacked only the proximity of the mountains, which, bordering the Nile Valley with rocks, brought abundant stone to it, thanks to which the Egyptians had the opportunity to build their temples and tombs for eternal existence out of durable material. The similarity of the natural conditions of Egypt and Mesopotamia, as Gommel particularly pointed out, corresponds to the similarity of some of the initial manifestations of their culture, namely the similarity of languages, writing, time counts, and religions. In the basic religious beliefs of both peoples, the deification of the celestial ocean Ana, or Well, from which the origin of the deities of air and earth, the sun and the moon, plays the same role. The worship of the deity of light in both nations occupied the first place, although the Babylonians worshiped, along with the sun and the moon, also stars to a greater extent than the Egyptians; even the animal symbolism of both nations, which was due to their belief in gods, is in many respects akin, although the Egyptians worshiped animals, perhaps under the influence of the superstitions of the original African population of their country, to a greater extent than the Babylonians.

From the similarity between local geographic conditions and between the main worldview, there were also points of contact between the Egyptian and ancient Mesopotamian arts. Nevertheless, no one can accept the work of ancient Egyptian art for the ancient Haldean; their similarity does not go beyond what is determined by the equality of the stage of cultural development of both peoples.

Ancient Haldean art in its essential features is the art of the cities of the Sumerian south and the Semitic north, later the Babylonian state, which, leading with varying success in the struggle due to predominance, each had their own special kings until the Babylonian king Hammurabi did not connect the south of Babylon and north to one large ancient Babylonian state. According to Lehmann, this happened in 2231 BC. er., according to Gommel and Ed. Meyer, - much later. Century rule in Babylonia of the Kassites, which reached its greatest strength in the XV century BC. e., for the history of art give very little material; from the centuries immediately following, only isolated works of Babylonian art have survived. At that time, the Babylonian kingdom more and more fell under the power of its neighbor, Assyria, until finally in 689 the Assyrian king Sinaherib finally did not level Babylon with the land. The development of ancient Dutch art begins over 3 thousand years BC. e. and ends by 2000 BC. e., but the ancient Babylonian art, we could probably trace back to the VII century. BC e., if what was left of him, for the most part did not die under the ruins of the new Babylonian art. The Novo-Babylonian state, having existed for only one century (625-539 BC. E.) And having grown old during this time, gave rise to art, whose works surprised Jews and Greeks.

The Sumerians, who, in contrast to the Semites, in terms of language and constitution, seem to be related, on the one hand, to the Aryans, and on the other, to the Turks, are considered the creators of the whole of ancient Mesopotamian culture. Their literature, art, science, and religion were adopted by the Semitic Babylonians and Assyrians. Even their language continued to exist among Mesopotamian Semites in the sense of the sacred. The southern cities of the country remained purely Sumerian, of which Eridu is important in the history of art, located on the site of the current ruins of Abu Sharein, Sirpurla (Sirgullah, Sirtella, Lagash), on the site of the current Tello, Abraham's homeland, Ura in Chaldea, the present Mughayr (Mukadjyar ) and Lars (Senkereh). Previously, the Middle Babylonian cities of Uruk, the biblical Erech, whose ruins are now called Varka, and Nitspur (Niebuhr, Niffer), had sevended to Semitism. Purely Semitic were the northern Babylonian cities, of which Babylon himself and his sister Borzippa were buried under the ruins of Gillah, Birs-Nimrud and El-Qasr, whereas the traces of Agadi, whose identity with Akkad was not established by all researchers, and its sister Sippar reached us in the ruins of Abu Gabba.

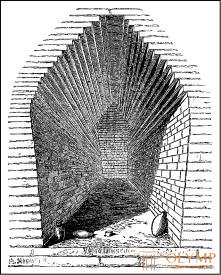

Fig. 147. Grave crypt in Ur. By Perrot and Shipie

Fig. 148. Vaulted gutter in Nippur. By "American Journal of Archeology"

The question whether the ancient Chaldeans used columns or pillars to support ceilings and roofs, to which they had recently given a negative answer, has now been resolved positively. In one building in Tello, the bricks of which are marked by the stamp of King Gudea and which, therefore, belongs to the first half of the 3rd millennium BC. e., de Sarzek found two thick pillars, each consisting of a compound of four round brick columns. A few hours from Tello, John Peters opened the building, the outer walls of which were dissected by massive semi-columns, and in one of the two internal premises of this building there were 18 brick columns with quadrangular bases arranged very closely, so this room is a real hypostyle hall. Peters refers this building to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. e. Needless to say, from all these brick columns, only fragments have survived. But it is possible to recognize in them that each row of bricks consisted of 6 pieces of a proper shape. The assumption that palm trunks were used to support the ceiling from the inside before such columns is even more likely. that in the semi-columns from the outside of the walls of the Chaldean buildings continued to exist, only turning into brick, those round trunks between which the clay walls were originally laid, and where these semi-columns were placed next to each other without any intervals, like organ pipes, such as in some parts of the facades of the palaces in Tello and Varka, timbered houses undoubtedly served as models for them.

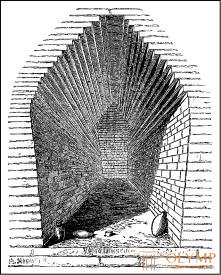

Fig. 149. Wall decoration in Varka. By Loftus

Regarding the decorative crowning of ancient Dutch buildings, which probably had tin roofs, we cannot get a clear idea for ourselves. The main facades were usually divided into four-sided or semicircular protrusions or recesses, with either the wide parts of the wall in the form of rizalits, or semi-columns and pillars arranged in a row with or without gaps, or, finally, the flat surface of the wall was diversified by conducting in-depth basics or breaking it into fields. It is much more difficult to answer the question about the decorative facing of ancient Dutch brick walls. It is impossible to recognize as a general rule that in Chaldean buildings a brick never appeared outside in its natural form, as Perrot and Shipié assumed. De Sarzek, Goethe and Maspero argued in a very definite way that the ancient palace of King Gudea in Sirpurle (Tello) had neither facing, nor inside, that is, its brick walls were not finished with anything. Nevertheless, there is no shortage of traces of facing other buildings. One - on the wall of the palace, opened by Loftus in Varka, was obviously covered with simple plaster, and in Abu Sharein, ancient Eridu, a rough image of a man with a bird in his hand was found on a piece of the inner surface of the wall. Also curious is another wall, uncovered by Loftus in Varca; it is divided into parts by semi-columns, standing side by side, like organ pipes, and, moreover, it is lined with a mosaic representing regular geometric figures made of small bricks of natural colors, yellow, red and black (fig. 149).

In Eridu, Taylor also found the remnants of a similar lining. But even more original is the third kind of wall decoration found in Uruk, namely, hollow bricks in the form of saucers, facing outward inwardness. Glazed brick, which played a prominent role in later Mesopotamian art, seems to have been in use also in Chaldea. Remains of a similar brick found in Mughayrah and Varka. In general, the appearance of the oldest Chaldean brick cities in terms of colors, it is believed, was not particularly different from the medieval brick cities of the North German Lowland.

In the ruins explored in the land of the Chaldeans, one can discern, just as in Egypt, buildings of a dual kind: religious and civil, temples and palaces.

The basis of the Chaldean temple, inherited by the Assyrian kingdom, was a massive terrace-like building. These terraces, or floors, upward gradually became smaller and smaller and connected with each other by external stairs. On the upper terrace stood a small, like a chapel, the sanctuary of the deity, decorated with special luxury, both outside and inside; before him were sacrificed. The building in the form of ledges, or terraces, which we have already seen in many nations, is the simplest, most primitive method, especially convenient on vast plains, for ascending the inhabitants of the heavenly god over the mist and everyday life of the city so that it is visible to every believer from a far distance. The temple had a rectangular shape; each upper floor was built indented to the rear, narrow side, so that in front of each terrace there was enough space for a long staircase that went straight up. With a square plan, the upper floors decreased evenly on all four sides, with the staircase, breaking into pieces at right angles, going on all four sides of this stepping pyramid. The rectangular type of the building dominated the Sumerian south, square in terms of the lateral pyramids prevailed in the Semitic north.

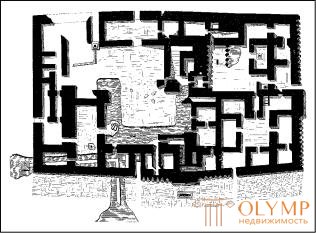

Fig. 150. Plan of the palace of King Gudea in Tello. By Goethe and de Sarzek

The Chaldean palaces, with the facades of which we have already seen a few, consisted of a number of rooms and halls grouped around large and small courtyards. The most famous plan of the palace of King Gudea in Tello (Fig. 150). In this building, erected over 3 thousand years BC. e., have not yet been used columns to support the ceiling, but on the two facades can be seen that they were divided into parts alternately half-columns, sided to one another, and wall ledges with a stepped profile. The earliest of the buildings, opened by Peters near Tello, as well as the single-piece wall covering of the palace in the ruins of Vusvas in Varka, date back to later times. Thus, there is no doubt that buildings made of raw brick without columns from the time of King Gudea belong to an earlier era, and buildings with columns and wall cladding represent the latest stage of the development of ancient-Dutch architecture.

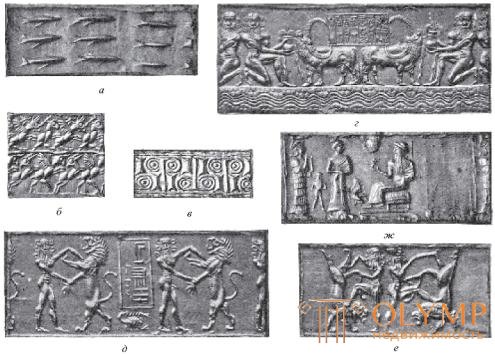

The deep antiquity of the ancient Haldean-Babylonian art is also shown in the decorations of its other works. The repetition of the fish figure on the same ancient Babylonian cylindrical seal in the Leclerc collection (Fig. 151, a ), just like the repeated repetition of the same motif - a deer pursued by a water monster, on the same Tello cylinder located in the Louvre, in Paris (b), are already almost animal ornamentation . But the vegetative ornamentation at that time was still completely alien to the ancient Babylonian art. The most ancient rosette, having some similarity of a flower, is found for the first time on the tiara of the king, depicted on a boundary stone of the XII century BC. e. (cf. fig. 164). Patterns, sometimes reminiscent of this kind of ornament on cylindrical seals, are nothing more than a solar disk emitting rays; this image, along with the image of the moon, which already at that time was given the outline of the Turkish crescent, was repeated countless times as a symbol of the god of light reigning over the universe. Similarly, one should not mix a disk surrounded by seven planets or containing them in oneself with a plant rosette. Wavy lines usually mean water. But more often in Ancient Chaldea, a simple geometric pattern was used, which is formed by the famous terracotta pins in the aforementioned wall facing (see Fig. 149).The diamonds inserted one next to the other alternate here with light and dark triangles arranged in a checkerboard pattern, and with patterns of zigzag parallel lines. The same diamond fields are preserved on one piece of stone found in Tello. Concentric circles are found filling some space on ancient cylindrical seals. On one such cylinder in the Leclerc collection, we see perfectly arranged T- shaped figures with twisted ends of the upper part, alternating with rectangular shields (Fig. 151, c). On the ancient relief of Tello, depicting the full emblem of the city, a ribbon ornament was found, that is, an ornament of undoubtedly of technical origin (Fig. 152). With the exception of this emblem, all the mentioned ornaments resemble the art of primitive peoples.

Fig. 151. Ancient Haldean cylindrical seals. By Menan (a, c, d, e, f, g), Goethe and de Sarzeku (b)

Fig. 152. Chaldean relief with a ribbon ornament. By Goethe and de Sarzek

At the heart of ancient Jewish art is sculpture, and above all plastic images of a person. Without crossing the boundaries of the archaic stages of the development of sculpture, these works leave far behind everything that we know at this stage, with the exception of the monuments of Egypt; observation of nature is wonderfully combined with style in them. Statues of diorite (or dolerite) in the Louvre, in Paris, give us an idea of Chaldean large sculpture ; they were discovered at Tello only in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. In the works of decorative sculpturing and samples of small plastic artworks of the ancient Haldean era, European collections have long been lacking. Cylindrical prints of marble, rock crystal, lapis lazuli, hematite, jasper and even more expensive semi-noble stones reached us by hundreds from all centuries of Mesopotamian culture. According to the inscriptions on them, researchers such as Menant, had the opportunity to determine, at least for the most important specimens, the time and place of origin. These deep-cut plastic images, most often reproducing mythological scenes from the two great ancient Babylonian heroic poems, or liturgical rites, were intended for making prints on soft clay boards, which in Mesopotamia replaced writing paper, and the design on the prints was embossed. Small clay figures obtained from Mesopotamian excavations are nearly as numerous; but determining the time and place of their origin is even more difficult than cylindrical seals. However, even here attempts were made to distinguish the ancient Haldean works from Assyrian and New Babylonian. Bronze figures of all epochs should be counted here. Already among the works found in Tello, it is possible to distinguish large bronzes of knockout work from smaller cast bronze. Slightly embossed images are preserved on clay boards and fragments of memorial pillars and other works.

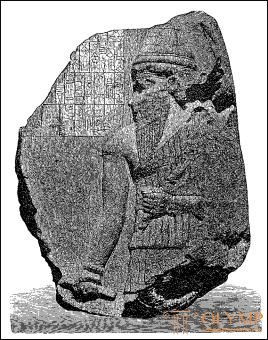

Fig. 153. Relief of King Naramsin. According to Gommel

Fig. 154. Fragment of the Ancient Haldean arc-shaped stone wall finish. By Goethe and de Sarzek

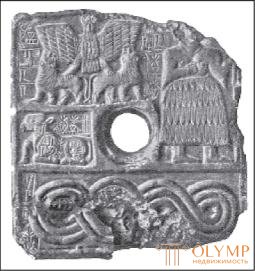

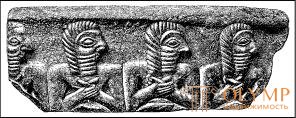

Of the plastic works of Tello, which could have been attributed to an even more ancient era than the era of King Urnina, one should point to fragments of the arched stone decoration of the wall, decorated with relief belt images of the same nude male figure (Fig. 154). Each of them has a hand on the chest, represented by en face, with the right hand supporting the left; heads turned in profile. Because of the aquiline nose that makes up the immediate continuation of a very low forehead, the whole head has a birdlike appearance. Hair on the head and beard are depicted in the form of wavy lines. The angular, almost diamond-shaped eye, despite the profile position of the head, is drawn en face and occupies a large part of the entire face under a thick, arched eyebrow, while a small mouth is almost lost in the beard. Thumbs are ugly big. In general, the impression of art is childishly inept, but with all its incompetence, strong in design.

The works with the name of the king Urnina inscribed on them primarily belong to a fragment of gray stone with relief, probably placed in the form of the city's coat of arms over one of the palace gates in Sirpurla (Lagash). It depicts an eagle with a lion's head, spreading its wings over two lions symmetrically standing back to it. This oldest of all known coats of arms in the world, in which the heraldic style is clearly expressed, has been preserved in its entirety on a small relief of small size (see fig. 152), and also engraved on one silver vessel of the same epoch. But the style of the figures from the time of the Urnina can be best studied with the help of stone relief, depicting, judging from the inscription on it, the king and his relatives. All figures are presented in profile, one - in the turn to the left, others - to the right. The head of the genus is distinguished by its size. The upper parts of the naked bodies have the same position as in the arcuate relief described above. The lower parts are covered with bell-shaped clothing with pieces of fur, forming folds. The flat feet of the legs are rotated accordingly to the profile of the head, the type of which does not differ in any way noticeably from the type of the above-mentioned older image. However, on all heads, with the exception of only one, the hair and beard are trimmed, and in the outlines of the eye, ear and mouth more attentive observation of nature appears.

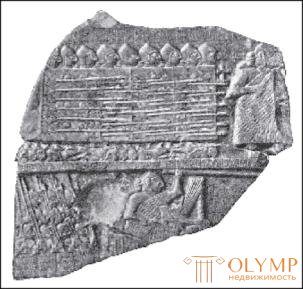

Fig. 155. The military scene on the stele of the kites of King Eannatum. By Goethe and de Sarzek

Then you should point out the famous Stele of the Eannatum vultures. Only six fragments of this upstairs of a somewhat narrowing slab have been preserved, decorated on both sides with reliefs and inscriptions glorifying one of the king’s victories. Nevertheless, the main images, subdivided into several parts, can be discerned to some extent: the king is twice as large as his warriors; standing on a chariot, he pursues his defeated enemy (Fig. 155). The following are depicted: the burial of the dead, the solemn sacrifice on the occasion of the victory, the execution of prisoners, the king, personally killing the leader of the enemy army, kites flying off the battlefield and flying away with the heads of those who fell in powerful beaks. Separate images represent crowds of people or corpses piled one upon another. The artist observed the sequence of incidents and tried his hand at reproducing various motives of movement, but the figures had already received a permanent archaic Chaldean type: bird profile of the head, which is almost entirely occupied by the eye and nose, squeezed torso, flat foot, angular arms. The development of particulars is somewhat better than in more ancient monuments, although the present understanding of forms is still very far away. However, all the contours are outlined firmly and expediently. Goethe calls this monument, attributed to them by 4000 BC. e., "the oldest batalic picture in the world." According to the latest research, this stela is nothing more than the 3rd millennium BC. e. Fragments of similar monuments found in Sirpurle indicate that slabs with reliefs of this kind were made at the behest of kings in memory of their exploits and for decorating their palaces, just as the current crowned persons order battle paintings for the same purpose.

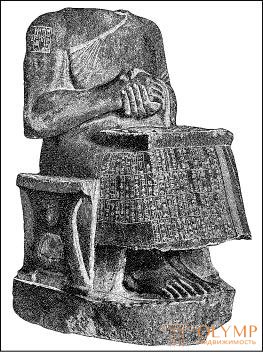

Fig. 156. Seated statue of Gudea, found in Tello. By Goethe and de Sarzek

Fig. 157. The standing statue of Gudea, found in Tello. By Goethe and de Sarzek

Transferring to the south, we find in Sirpurle a more mature art, which, however, does not refer to the 4th, but to the 3rd millennium BC. e., namely in the ten statues of greenish diorite found in the ruins of the palace in Tello. Unfortunately, none of them had a head; but separate heads were found, of which one, in all probability, belonged to any of these statues. One of these statues, abundantly covered with inscriptions, depicts King Urbau, while the remaining nine - the king or high priest Gudea in a different size. A small statue of Urbau, standing to his full height, lacks not only the head, but also the legs. Like the statues of Gudea, she depicts the king en face, draped only in a large quadrangular piece of fabric, forming a bell on her lower body, as if thrown over her left shoulder, so that her right shoulder and arm are left uncovered. But in reality, it differs from the statues of the successor of the named king in more archaic nature, expressed in the short and squeezed members and in a flatter, superficial designation of their forms, for example, in the complete absence of folds of clothing. Of the statues of Gudea, which, judging by the inscriptions on them, once stood in different temples, as offerings to the gods, four depict the king sitting, and four - full-length. In all, one can see a petrified symmetry, extending both to the upper and lower limbs, and therefore indicating a more ancient stage of the development of art than the frontality (according to Julius Lange). Hands lie one on the other on the chest, both legs, facing straight forward, parallel to each other, and although in the seated statues are sufficiently processed, they are too close to each other; in standing statues, due to their position, the heels disappear in the mass of the statue, but the feet are separated from one another by a small space. Body shapes are generally still rather shortened and broadened, but sometimes, like in life-size statues, the shoulders are too narrow, which seems to be due to the initial mass of a piece of diorite from which they are carved. It is necessary, however, to note that in all these statues we see a true, quite consciously executed reproduction of the human body. The anatomist’s modern eye will find here deviations from perfect accuracy, but in general the nude body, although too fleshy, is fashioned correctly and softly, and on clothes that are intentionally smooth and stretched, folds and a fringe of fabric are marked in the proper places; if the elbows are too angular, and the hands are too flattened, then the fingers and toes with their joints and nails are sculptured with naturalness, leaving nothing to be desired. Only one of the seated statues is of colossal size. Of the rest, one represents King Gudea with a construction plan, the other with a scale on his knees (fig. 156). These neighborhoods, as well as many of the inscriptions on the buildings, apparently indicate the great importance the Mesopotamian kings attached to their construction activities. One of the smaller statues in full growth (Fig. 157) is distinguished by subtlety and freedom of execution. The head found near this torso is completely bare; the hair and beard are shaved smoothly, and only boldly arched eyebrows, fused over the nosebag, are sharply outlined. In general, it is a beautifully shaped head with large open eyes and full, regular features. Similar features, but made even thinner, we find in the other two, also smoothly shaved heads (Fig. 158, b), compared with which the so-called "head with a turban" has a more strict and more ancient character. Her more lively face is also smoothly shaved, but the lush curls on her head are depicted by perfectly regular small spiral lines and are tied over her forehead in the form of a tiara or turban (Fig. 158, a). One fragment of the bearded head is made, on the contrary, freely and softly, quite in accordance with the general freedom and softness that distinguishes the relief of Naramsin. Apparently, in the period between the ancient and later eras, when it was decided to grow hair and a beard, there was a period in which they were shaved or worn shortly cropped. Among the sculptures found during the previous excavations and recognized, based on the excavations in Tello, by the Ancient Kingdom, one should mention another small statue from the Louvre Museum, depicting a sitting woman with a big head, in hair dress (Fig. 159).

Fig. 158. Heads found in Tello. By Goethe and de Sarzek

Fig. 159. An ancient Royal Female statue. According to Goes

From the decorative sculptures of the time found in Tello, one must first of all point to a small round foot, on the lower step of which are squatting naked male figures leaning their backs to the middle cylinder. Remarkable is also the stone vase of King Gudea, the relief of which is a symbolic image consisting, exactly like the Greek caduceus, of two snakes coiled around the rod (fig. 160).

The further course of development of ancient Babylonian art is perhaps most conveniently traced through the history of cylindrical seals. But here it is not always easy to distinguish the truly ancient from the later, from imitating antiquity. In Sirpurla were found cylinders with images of the battles of Isdubar, similar to those with which we have already become acquainted.

Fig. 160. The stone vase of King Gudea with the image of a rod entwined with serpents. By Goethe and de Sarzek

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)