The history of Egyptian art has only recently been possible to study only from the end of the 3rd dynasty, and at the first stage of its development it can be likened, in the words of Lepsius, to a “child educated in severity, chastity and good morality”, which remained for all subsequent stages. For the first time, excavations and surveys of the XIX century gave us the opportunity to get acquainted with the state of this art. The names of Flinders Petri, who found near Tuha, between Ballas and Negade, the tombs belonging to this early time, Amelino, who tore off five large ancient tombs of the Pharaohs near Abydos, and de Morgan, who found the tomb of the king in 1897 Menes, whom the Egyptians themselves considered the founder of the 1st dynasty of the pharaohs. Thanks to these scholars, Egyptian art of the era of the reign of the first three dynasties suddenly resurrected before us.

The most important finds concern the time when writing already existed. Finely ground flint weapons and labor tools are joined in a small amount by copper, and later bronze. We see here precisely how the prehistoric Neolithic epoch passes into the historical one, without losing, however, the traces of the initial stage of the Stone Age.

The Tomb of Menes was a rectangular, separately standing structure, built of unbaked bricks; the other tombs were deeply carved in the rocks and only lined with unbaked brick. Objects found in the tombs of this era are preserved in the museum of the city of Giza, in Cairo, and European collections. By the way, there are a lot of them in the Berlin Museum, in the “Detailed Index” of which they are distributed in a strictly scientific manner. The clay statue of "The Seated Woman", located in this museum, is portrayed by some palaeolithic images of southern France; in bearded figures, cut from the bone, the eyes are made from elephant's canine. Remarkable green slate plates, having the appearance of animals or a geometric shape, served to grind blush.

Among the products made of ivory, a private English collection, there is, among other things, a board published by Spiegelberg, which is especially interesting because it serves as evidence of the existence of a traditional motive in the early era — the king, who grabbed the enemy bowed in front of him and intent on killing him. Stone pots in the shape of animals (dogs, elephants, hippopotamuses) resemble works of ancient American art. Elsewhere there are relief images on green slate boards, which Steindorf considers to be a "new branch of Egyptian art." Two such boards are located in the museum of the city of Giza, and one of them shows a whole series of cows, donkeys, sheep and trees, arranged one above another in the form of four lanes; the other board represents the image of the Nile boat; two more such boards are located in the Louvre and the British Museum, in London. These stone reliefs of the early times of Egyptian history are more peculiar, sharply pronounced style than other works of the same era. The powerful forms and the extraordinary muscularity of the people and animals depicted here sometimes resemble the works of ancient Highdean art. In terms of costume and posture, people are completely different from the later Egyptians. That these reliefs belong to the most ancient pore of the Egyptian kingdom, we, together with Steindorf, recognize no doubt.

The earthen vessels of the time of the first three dynasties were made exclusively by hand, but sometimes also with the help of a potter's wheel. The clay basket indicates that basket weaving preceded pottery production. Along with black bowls, on which, like on Neolithic, geometric patterns are drawn with white paint, there are pots painted with reddish-brown paint on a light background and white paint on red.

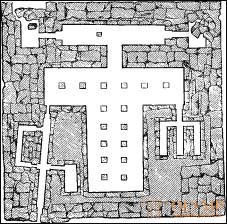

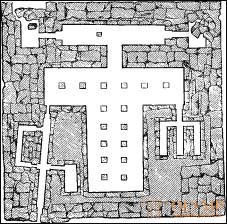

Fig. 106. The plan of the temple of the Sphinx near Giza. By Perrot and Shipie

Ornamental motifs in the painting of this kind are wavy and zigzag lines, as well as real spirals. Schweinfurt, according to the opinion expressed by us above, believed that some vessels completely covered with narrow spirals borrowed these forms from the nummulite limestone common in Egypt. Among the ornaments on the vases there are human figures, male and female, and animal figures, such as stone sheep, deer, crocodile and ostrich. Schweinfurt found drawings depicting a flamingo with a spiral head and dancers with hands also in the form of spirals; there are images of a rook sailing through the firmament, and often clay vessels entirely receive the appearance of a similar boat — a vessel carrying souls of the dead. The motives of the vegetable kingdom, although rare, are found. Everywhere the beginnings of later Egyptian art appear.

About the art of the Old Kingdom, beginning with the 3rd dynasty, almost the tombs of the great and noble Egyptians alone give us the concept. The few remaining ruins of the temples - the true monuments of the initial religious architecture of Egypt - indicate that there was a close connection between the abodes of the gods and the tombs of the dead. Examples of structures of this kind can be, firstly, the small temple-tomb of Pharaoh Snofru, near the pyramid in Medum, from two halls that have no decorations, and from the courtyard, secondly, the Sphinx temple in Giza, dating back to built pyramids. Its plan (without the enclosed space adjacent to it) in general terms represents two halls adjoining one another and forming a similarity to the letter T (Fig. 106). The flat stone ceiling was supported in the transverse hall by six smooth four-sided pillars, in the longitudinal hall - by ten similar pillars, standing in two rows. These columns do not have plinths either at the base or above the top. The stone ceiling beams rest directly on the pillars. This temple is a sample of a stone structure of the most ancient type, occurring, perhaps, directly from dolmens, but distinguished by carefulness and correctness of laying (Fig. 107).

There is no painting or other decorations, no writing in this simple building; but its pillars are carved from pinkish-red granite, and the walls and ceiling are made of alabaster, so that from this small architectural monument of antiquity blows noble, graceful simplicity.

The tombs of the Egyptian kings are the pyramids; octagonal burial structures with a flat roof and walls, which had the appearance of slopes outside, served as tombs for the nobles. These tombs are called mastaba. The most significant pyramids and mastabas are located near the ancient capital of Egypt, Memphis, in a desert area on the west bank of the Nile. In the west, divine heavenly bodies come in every day, and therefore the Egyptians assumed the existence of a kingdom there, where the dead are in blissful union with the gods.

Fig. 107. Temple of the Sphinx near Giza. By Perrot and Shipie

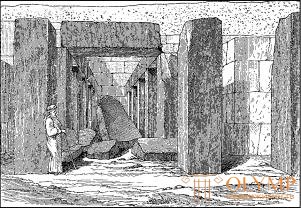

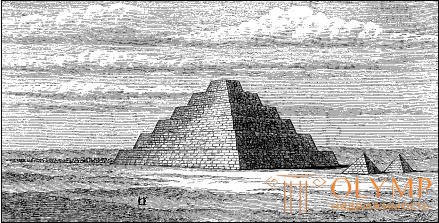

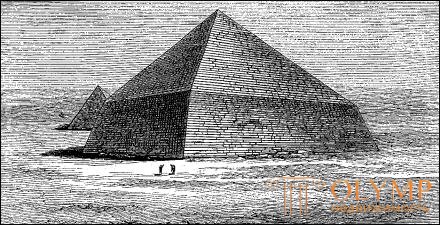

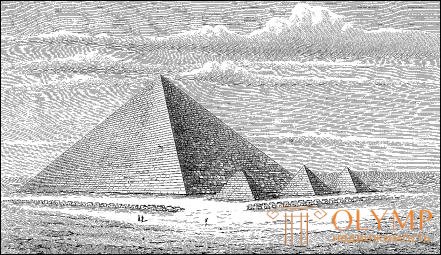

Pyramids are the most grandiose and typical monuments of art of the millennium under consideration. The burial crypts in the pyramids, which had to be penetrated along long corridors or shafts, were sometimes placed in solid, built of stone or brick, thicker than the building itself or below it, in stony soil. The chambers that served to offer sacrifices or were dedicated to the cult of the deceased were usually held in the form of a special building on the east side of the pyramid. In artistic terms, their appearance mainly deserves attention in the pyramids. Representing a petrified giant stereogram mound that received the correct stereometric shape, they hit the viewer with a mass of stones piled on top of each other and their slender tetrahedral. Subsequently, the ancient Greco-Roman world called the pyramids one of the wonders of the world. From the point of view of the laws of historical development, it seems certain, as it is recognized by all, that the oldest of all pyramids is the tomb of Djoser, the pharaoh of the 3rd dynasty (fig. 108), the sacred pyramid at Saqqara, consisting of six huge, diminishing with the approach to the top parts of limestone and reaching a height of 60 meters. We have already seen earlier that the concessive form is nothing but the initial, stylized earthen mound that already appeared among some primitive peoples; The pyramids were also built first in the form of ledges, but then they were supplemented with stone slabs so that at the end they represented smooth edges. The Sakkarsky pyramid, concealed under its heavy mass, was lined with a greenish tile, a chamber that was restored during the 20th dynasty, distinguished by a love of antiquity; but judging by her jewels in general, it was built under King Djoser. The pattern of the wall cladding, the pieces of which fell into the Berlin Museum, resembles a weaving. Pharaoh Djoser was succeeded by Pharaoh Snothru, whose tomb - the pyramid in Medum - no longer has a stepped, but a smooth form. We find the transition from one type of pyramid to another in Dashura, where the pyramid is, as it were, placed on another, truncated and having steeper edges (Fig. 109). In any case, the pyramids with smooth edges are the most pure and complete spokesmen of the idea of such structures. The greatest and most famous of these pyramids are located near Giza. These are the tombs of the three kings of the 4th dynasty: Khufu (Cheops), Khafre (Khafre), and Menkere (Mykerina). The largest and most ancient of them is the pyramid of Cheops (Fig. 110), having 233 meters at the base, both in length and width, and reaching 145 meters in height. The few remaining parts of its stone lining consist of white limestone, which, having been painted in different colors, should have once produced the impression of a combination of several precious rocks. The second pyramid, the tomb of Khafre, was slightly smaller. Its height was 135 meters; the lining of its lower part consisted of pinkish-reddish granite. The third, the pyramid of Mikerina, was only 66 meters high. In its lower part, it was faced with syenite, and in the upper part - with limestone. A sarcophagus of bluish-black basalt with the mummy of the Pharaoh in a wooden coffin, which was drowned during its transportation by sea to London, but known from drawings, was found there. He gives us an idea of the type and style of ancient Egyptian earthenware and wooden buildings. But since German Egyptology recently recognized it as a work of the 26th dynasty, which restored the tombs of the ancient kings in a modified form, instead of this sarcophagus a magnificent example of ancient Egyptian architecture can serve as a sarcophagus of Khufu-Onk (4th dynasty) made of pink granite. the Museum of Giza; it is also a kind of a clay-wooden structure with doors and windows, although with a less developed device of frames and jambs.

Fig. 108. Sakkarskaya pyramid concession (restoration). By perring

Fig. 109. Dashur pyramid (restoration). By perring

Fig. 110. Pyramid of Cheops (restoration). By perring

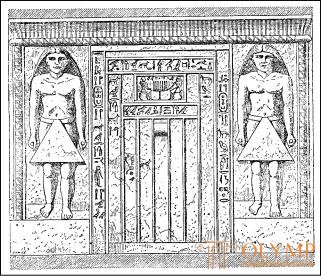

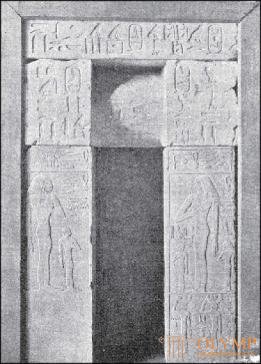

Fig. 111. The door of the appearance of the mastaba in Giza. According to Lepsius

Mastab, the tombs of noble people, located near the pyramids, from an artistic point of view, are curious, not so much in their appearance, as in their internal structure. Mastaba is represented on the outside as a rectangular mound formed by itself from the earth dug from the grave and poured on the coffin. Inside the mastaba is especially interesting the sacrificial peace, or sanctuary, intended for the cult of the deceased; the entrance door to this peace was always in the eastern wall, and opposite it, in the western wall, from the inside, there was a so-called appearance door, signifying the entrance to the realm of the dead, which later turned into a vertical plate (stela). Slightly embossed, illuminated images, adorning the inner walls and the door of appearance in these tombs, give them great artistic and historical significance. In addition, thanks to them, we have the opportunity to become more closely acquainted with the clay-wooden architecture of the Old Kingdom. The appearance doors, or steles of many tombs of this period, such as, for example, the stele of the sacrificial peace of King Manofer from the 5th dynasty, located in the Berlin Museum (Fig. 111), or a similar door, published by Lepsius and located in the Giza Museum, introduce us with two main motifs of ornamentation of all subsequent Egyptian temples architecture: with a round pillar, entwined with colored stripes, serving for vertical edging of spaces, and with a grooved, painted with stylized reed leaves (?), which usually end top of the wall and the door. The only plant motif that appears in the ornamentation of this genus is the double papyrus flower (according to some, the lotus flower), crowning here and there images of vertical pillars. Two flowers on long stems, tightly tied at the cups and slightly curved, lean to the right and left (Fig. 112, a). Between the images of the pillars there are narrow, long spaces covered with a floral, chess, rhomboidal or zigzag pattern; upon closer inspection, it turns out that this pattern represents mats that were hung here in reality. For example, the mats on the eastern wall of the Sakkar Tomb of Ptahotepa (5th dynasty) are depicted as if they can be lowered and raised. Nonetheless, an inexperienced observer will see nothing in this wall ornament except a combination of geometric lines.

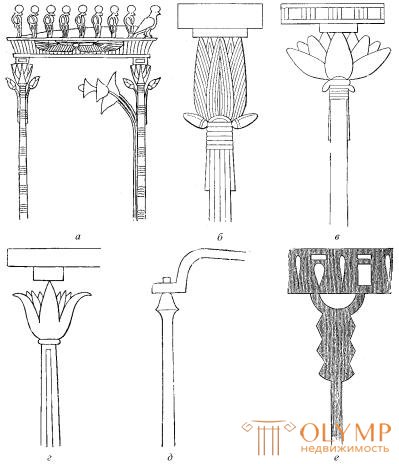

Fig. 112. Development of the Egyptian capital. By Delafoua (a), Pruss-d'Avenue (b, c) and Lepsius (d, e, f)

Fig. 113. Ty and his spouse. Picture from the tomb in Memphis (5th dynasty). According to Priss d'Aveno

Along with all this band-like ornamentation, which sometimes has the character of weaving, in the sacrificial chambers there are images of light tent-like structures (aediculae) on widely spaced wooden supports. Here are especially interesting images of pillars, resembling the ornamentation of the capitals of the Egyptian column, which does not correspond to its purpose - to serve as a support. Thin wooden columns had the appearance of separate trunks of plants, but along with them there were columns in the form of a bundle of trunks. Among the images of this genus, most often there are columns in the form of not yet flourishing or blooming lotus trunks, whereas papyrus columns are rare. Wooden pillars with buds and flowers attached to them are found in the reproduction of a single wooden structure located in the Louvre (see Fig. 112, a). Capitals from Sakkara (4th dynasty) have the form of a bud or a flower (b, c); and a sample of capitals in the form of a half-open lotus (g) taken from the tomb of the 5th dynasty. A subsequently changed stone cap in the shape of an overturned bowl or bell (e), apparently derived simply from the pole of the tent, as well as a capitus in the shape of a cowhide (e), according to Lepsius, appear already in the images of light buildings (aediculae) 5th and 6th dynasties.

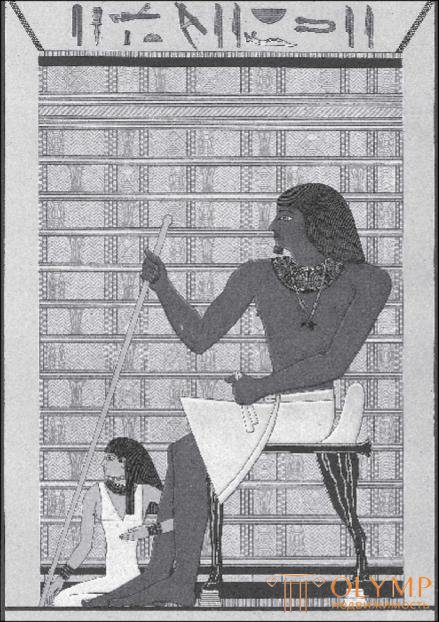

The figured images on the plane in these tombs are almost exclusively in painted slightly convex paintings (Fig. 113). Such images, despite all their schematic irregularities, are vital, expressive and intelligible. People - broad shoulders and roots. In some images, such as, for example, in the tomb of Ti, the shoulders and arms are, as it were, casually represented almost in profile. The images of animals in various poses are especially natural; the horse is still missing, but donkeys, cows, sheep, and gazelles are reproduced with love, in their natural form and characteristic movements. The range of colors is very simple. Yellow, red, blue, green, brown, white and black colors do not yet have any shades. Paintings on steles or doors of tombs depicting the deceased should not be mixed with real wall painting. The subject of the latter is also the deceased. Pictured in full size, he sits at one end of the wall in front of his servants and observes their work or accepts gifts from them. The working servants are reproduced by stripes placed one above the other, and the height of each figure rarely exceeds the size of a foot. To what extent this arrangement of the composition with stripes was later replaced by an attempt to present a perspective removal shows, for example, the famous drawing in the tomb of Ptahotep in Saqqara. The artist wanted to paint a picture that reproduces the life of the whole plain, from the Nile to the tombs of the desert, and executed it by drawing several stripes, one above the other. Below, in the first lane, there is a river swarming with fishes with boats floating on it, in the second lane - catching birds, in the third - building a ship, as well as catching and salting fish; in the fourth - the hunt for antelope, in the fifth - the desert with wild animals.

Fig. 114. Stela Shiri. By Maspero

The tombstones of Shiri, the 3rd dynasty, the Museum of Giza (fig. 114) are considered to be the oldest tomb images on the door-stones of the tomb of Shiri. The time of the pharaoh Snefru includes the sacrificial peace of the high priest Amten, the Berlin Museum;here the images are flat, but clearly and sharply modeled. By the epoch of the 4th dynasty belonged the sacrificial peace of Prince Merab, the Berlin Museum. It is particularly noteworthy image of the rook of the dead, in which Merab goes to the country of eternal bliss.

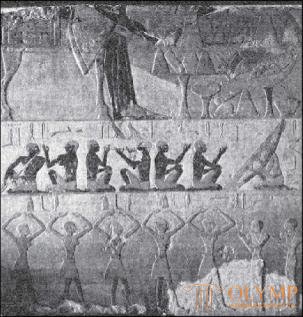

The tombs of the 5th dynasty, found in Saqqara, give us an idea of the full bloom of the Egyptian ancient kingdom. Of these, one can point to the coffin of the main royal barber Manofer, with numerous images of animals, and the coffin of Pegenuki, with beautiful scenes from the life of the shipmen, both in the Berlin Museum, mainly to the famous tombs of Ti and Ptahotepa at Saqqara. In the tomb of Ti, we find, in addition to the usual images of various foods presented to the deceased, drawings representing plowing villagers, grinding women, working oxen and donkeys, men playing musical instruments, and dancing girls (Fig. 115). In the tomb of Pta-hotepa, one should especially note the images of hunting in the desert, grape harvesting and catching birds in the swamp.In all these pictures, we are amazed, in addition to the different power of reproduction, of the freshness and immediacy of feeling, with which the artist constantly manages to convey the plot clearly and vitally. But if clarity and clarity is achieved in the image of this or that plot, it has always, for centuries, been reproduced in the same form.

Fig. 115. The wall in the tomb of Ti. From the photo of Brugsch

In the tomb paintings of the Old Kingdom there are no images of pharaohs and gods; stone reliefs in Wadi Maghara in Sinai, representing Khufu (Cheops), who seized his Asian captives by hair and sacrificing them to the gods, are commemorative tables of the king’s deeds and, as they have nothing in common with the cult of the dead, are an exception among the extant works of art of the ancient kingdom.

To study the round plastic monuments of the epoch in question, we must once again be transported to the world of tombs. The colossal sphinx of Giza, which was considered an exception, belongs, as certified by Borchardt, to the Middle Kingdom. The huge, sculptured stone statues of pharaohs of the Old Kingdom found in one of the underground corridors of the Sphinx temple, German scholars (Schweinfurt, Borchardt, etc.) recognize the 25th and 26th dynasties as archaistic works.

That the original works of the Old Kingdom served as models for them can be assumed, but not asserted with confidence.

A special position is also occupied by the figures of chased work made of copper plates and, possibly, initially gilded, discovered in the ancient ruins of the Gierakonpolis temple. The full-length statue depicts Pepy I, the pharaoh of the 6th dynasty, and the smaller statue transferred to the Museum of Giza is probably the son of this sovereign, Mefusufis. According to the portraiture of heads and the vitality of execution, these sculptures have the character of the latest, most mature sculptures of the Old Kingdom.

Fig. 116. Statue of Methen (Amten). From the photo

Found in the private tombs of this kingdom, the figurines and frontal groups of figures, either made of wood or limestone, depict almost exclusively wealthy private individuals, their servants and maidservants. Such statues and statues were placed in special deaf chambers that were located in the mastaba and were known as serdabs; they were put there in order to provide the dead with eternal life and furnish it with comforts. Despite their primitive frontality, these statues are the most realistic and vital plastic images of people in all of Egyptian, moreover, in all Eastern art. Only the Greeks in this respect caught up and surpassed the Egyptians. Borchardt devoted extensive research to the statues of the servants of the Old Kingdom kept in the Museum of Giza. Limestone statues come from Sakkar tombs, wooden - from the Meur tombs. Among those and others, we find, apart from the priests who accompanied the deceased to the afterlife, figures of porters, millers, bakers, blowers of fire, butchers, brewers, coopers, etc. All these figures are broad-shouldered and stocky; in them (as Steindorf points out) one can already notice some transition from archaic stiffness to greater freedom of postures and movements.

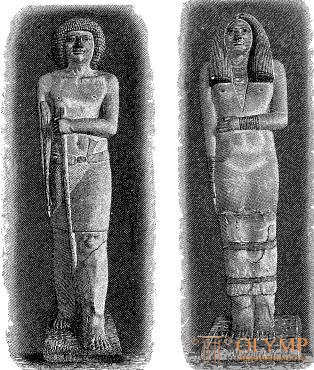

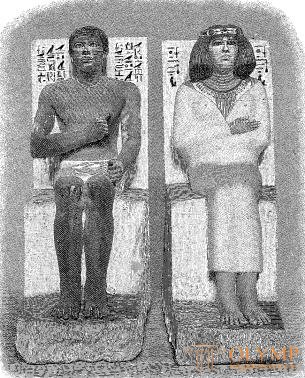

Archaic works, such as the statues of Anhwa in the British Museum and Methen (Amten) in the Berlin Museum (fig. 116), belong to the initial times of the 4th dynasty. These figures, represented by the seated, barely reach one meter in height. Their head is disproportionately large, one hand pressed to the chest, while the other, stretched forward, lies on the knee. These works include two pieces of limestone, almost the size of statues of the Louvre Museum, of which the male depicts a certain Sepu (Fig. 117, left) and the female Nezu (Fig. 117, right). Well-known poses that are also sculpted from limestone (about 1.2 meters high) in the statue of Amenhotep and his spouse or sister Nefertiti in the Museum of Giza, which should be recognized as belonging to the later period of the 40th dynasty (Fig. 118), differ in much more ease.

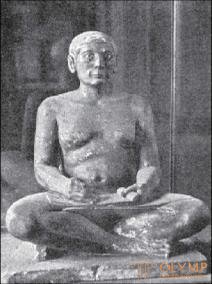

Fig. 117. Statues of Sepa and Nezu. With photos of Girodon

Painted in dark paint, a man with short cropped hair on his head, all of whose clothing consists of an apron and lace on his neck, keeps his right hand still pressed to his chest, as in more ancient statues. The woman, painted in a lighter paint, is wrapped in a tight-fitting clothes, from which only the right hand on her chest was exposed; Nefertiti's thick hair falls from her head onto her shoulders and is surrounded by a diadem, the decorations of which, according to Godfir, represent the most ancient ornamental motif - a lotus flower, and in our opinion, nothing more than a star. The faces of both figures are peculiarly expressive. In addition to these statues, several other, larger and smaller sizes that make up the glory of the 4th and 5th dynasties, and, above all, the famous "Scribe" from the Louvre Museum in Paris (fig. 119), carved from limestone, have come down to us. and painted red. The scribe sits on the ground, with her legs tucked under herself, holds the papyrus with her left hand on her lap, and the cane wand used for writing in her right hand and looks straight, smiling. The protein of the eye is made of quartz and bordered with bronze eyelids; the pupil is a circle of rock crystal and a metal dot inserted into it. The hair on the head is shortly cropped, the cheekbones stand out strongly; chest, arms, knees are completely natural, and only the preloaded legs are depicted less correctly. Similar solitary limestone statues are abundant in the Museum of Giza. In Louvre limestone statues, forming family groups, various postures are attached to figures that maintain their frontal position. Sometimes the husband is sitting, and the wife, the same height as him, is standing near, with his left hand on his shoulder. In other cases, the couple are sitting side by side, and between them is a small child, holding the index finger of his right hand at the lips. In one group of the Berlin Museum, there is only one husband; the smaller wife is kneeling beside him, and her son is beside her. Father's eyes are made of stone and copper. Numerous small statues of the museum in Giza depict the whole staff of the deceased. One of the servants, squatting, with an expression of sorrow, laid his left hand on his head. Here we see a naked young man walking with a bag over his shoulders and a bouquet of flowers in his right hand down; there the servants and maids, standing or kneeling, rub the grain or knead the dough on the stones. Despite the frontal position of the figures, the motives of their movement everywhere are very natural.

Fig. 118. Limestone statues of Amenhotep and Nefertiti. From the photo of Brugsch

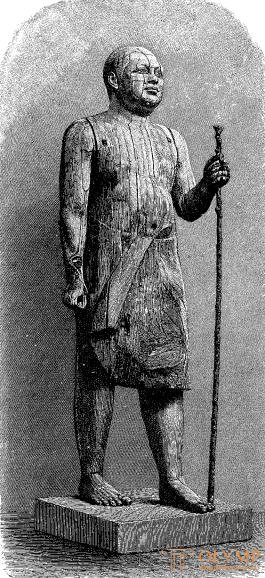

Just as from the series of limestone statues of the Old Kingdom, the “Scribe” of the Louvre Museum stands out, among the wooden statues of the same period, the first place belongs to the “Village Headman” of the museum in Giza (Fig. 120). The pedestal of this standing figure is lost, as well as its finely painted canvas sheath, but everything else in it is well preserved. Reproduced in her tightly folded, obese man - realistic and typical no less than the figure of a thin "scribe." The tree also features an excellent statue of the Chief Gardener Pearnofret, the Berlin Museum; it is also extremely natural and in its slimness is the opposite of the portly figure of the "elder". In general, it should be noted that such proximity to nature, as we see in the sculpture of the Old Kingdom, Egyptian art, depicting individual figures, never reached its later stages of development.

Fig. 120. Village headman. Egyptian wooden statue. From the photo

Fig. 119. Scribe. Egyptian limestone statue. With photos of Girodon

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)