The history of art of primitive and semi-cultural peoples familiar with metals, brought us from Africa to the East, to the Malayan Islands, and from there led further further in the same direction, across the ocean, to the ancient American peoples, whom we hardly have the right to call semi-cultural. Organized state life, the established religion, the established written language - these are the preconditions of that higher civilization, the mature fruits of which are the sciences, and the most magnificent colors are the arts. Without a doubt, American cultural nations to some degree possessed all of this; nevertheless, they only moderately exalted the semi-culture of those Indians whom we were to rank among primitive peoples. Their development stopped halfway to the culture that they could, but could only be, achieved. Therefore, we cannot regard their art in connection with the art of the cultural peoples of Asia, the banks of the Nile and Europe, but should look at it as the final phase of the artistic development of prehistoric and primitive peoples, in some way as the highest stage in the development of their art.

The ancient cultural peoples of America lived in a space bounded from the north and south that included the current states of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua in its northern part, that is, from one ocean to another, in South America, beginning with Colombia, settled relatively narrow strip along the coast of the Pacific Ocean, in the space of the present regions of Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. Although in this way the culture of ancient America developed exclusively within the tropical belt, however, the influence of the local heat itself was experienced only in relatively few marshy or steppe coastal areas of the aforementioned space. But the main centers of culture lay in temperate, sometimes even climate-harsh mountain areas, in Mexico at an altitude of 1,500 to 3,000 feet, and in Peru even up to 4,000 feet above the sea surface — areas where they are almost twice as high as these plateaus volcanoes. Mexicans (Nagua tribes, Toltec, Aztec) in the north and Peruvians (Aymara, young women, Inca-Peruvians) in the south are considered the most important representatives of ancient American culture. But along with the Mexican Toltec and Aztec cultures in Central America, there existed mainly on the Yucatan Peninsula, which surpassed the Mayan Mexican culture, from which Mexicans, perhaps, borrowed the beginnings of their culture. In the northern part of South America, in present-day Colombia, also next to the Inca culture, an independent culture of the Chibcha tribes developed.

But, noting the fact that a certain difference is noticed between the cultural areas of these tribes, you will still have to attach greater importance to the similarity that unites them - kinship. It is this similarity in the results achieved by the main tribes - provided that they are independent of each other’s development and beyond the possibility of borrowing from outside - that serves as proof of the basic unity of the American national type. The view that the whole culture of the ancient American people is an alienated part of the higher culture of the Old World is considered to be erroneous, but its very close connection with the semiculture of numerous local Indian tribes is recognized as the same semi-culture that we still see in these tribes; Thus, the ancient culture of Central America is only the latest, higher stage of this local, national development. As for the actual or only apparent similarities in the works of American culture with the works of the Old World, it can undoubtedly be sufficiently explained by the uniformity of human nature: similar cultural conditions give rise to similar works. Religion of North American Indians, the essence of which consists mainly in honoring the ancestors of the family and tribe in connection with the spiritualization of everything, is in undoubted connection with the polytheism of ancient American cultural peoples that developed to a degree fully developed cult; They worshiped the deities of the sky, especially the sun, moon, fertilizing heavenly rain and the four cardinal points, but countless deities — patrons of families and tribes (that is, ancestors) —who even human sacrifices played a very prominent role. Even the Indians of North America tried to express their thoughts with the help of signs, and here we see that the results achieved in this respect by the cultural American peoples derive directly from these attempts. Peruvians are not far from the Indians: they actually only replaced the Wampum belts of the Iroquois and Hurons with multi-colored cords with knots located on them in various ways, but the Aztec ideographic letter, already at least when writing your own names, is known phonetic element - trying to fix sounds. Shellgaz proved that the Mayan tribes, whose letter is also ideologically based, going further along the same path of development, used an even greater number of phonetic signs. The less developed tribesmen of American cultural nations still live entirely in the setting of the Stone Age, but they themselves did not go further than the transitional state from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age. True, they had already processed gold, silver, copper, tin and lead, knew how to smelt, cast and forge these metals, received through mixing bronze about the same as the prehistoric peoples of the Old World; but their tools and weapons were mostly stone, and the extraction and processing of iron remained completely unknown to them. Speaking about the architecture of ancient American cultural peoples, it should be noted that the lagging pyramids - a type of buildings, at first glance stopping the observer’s special attention to itself - in fact turn out to be nothing more than a natural development of various types of buildings that we saw earlier on the Polynesian islands, and the name "mounds" and the more primitive Indian tribes; even the comparatively advanced ornamentation of these peoples directly follows from the beginnings we have seen in other nations.

Since the time of the studies, Bandelie is becoming more and more certain that the Spanish conquerors and their historians, partly unwittingly, partly intentionally, exaggerated in their descriptions the education of the Mexicans, the Mayan and Peruvian-Incas. But, on the other hand, one should beware of the opposite extreme and recognize the cultural development of these peoples as still very high. Recall that they had a timescale, scientifically based on precise observation of the relationship of the earth to the sun and moon, that agriculture flourished in Mexico and Peru, that even full and complex clothing distinguished them from primitive peoples of any part of the world. Roads, which they conducted with great skill, without being hampered by the highest and steep mountains, construction of an extensive and complex system of canals due to excessive dryness of the soil, all this is a reality that existed, not empty fables, just like those treasures and the mass of gold that the Spaniards exported from Mexico and Peru and melted; not fables, too, and huge stone buildings, in a variety found in the whole space where these peoples lived, and which, during the Spanish invasion, had already been abandoned and destroyed.

On the history of the development of ancient American art, in the strict sense of the word, there can still be no question. To do this, we have too few undoubted, positive data that would allow us to distinguish works of more ancient from newer and accurately determine the epoch of their origin. For centuries, the most ancient works older than the Spanish conquest are very likely, but there can be no talk of millennia, even one millennium. In view of the fact that American art could not influence the art of other parts of the world, we have to dwell not so much on the ups and downs of its internal development, which did not matter for the development of the art of humanity in general, but rather on its difference, taken as a whole, from the art of primitive peoples. .

In ancient America, we meet for the first time a developed stone architecture. Its main monuments are temples and palaces. The material for these buildings served as part of correctly hewn, tetrahedral stones, sometimes interconnected with cement, and partly - especially among the Peruvian Incas - irregularly shaped boulders, which were shaped like so-called cyclopean walls. Sometimes the walls were erected from small unpolished stone or unbaked brick and only revetted with large stone slabs or colored plaster. The roofs of these stone palaces, usually either flat or lugged, were made of wooden beams and straw. But in some cases, especially in the areas of the Maya tribes and in Peru, there were also stone roofs consisting of slabs lying on the ground; This kind of roof is usually called octahedral or trihedral arch, although this is not entirely accurate. Attempts to arrange these arches are found only occasionally and on a small scale. In the middle of large halls, in some cases, remains of pillars of various kinds, round and straight, were used to support the ceiling beams; sometimes these pillars are richly decorated with sculptural ornaments; in the Mayan countries they are covered with hieroglyphs, in some places even sculpted in the form of whole human figures of caryatids or Atlantes, but only in very rare cases the bases and capitals bring these columns to the value of a real, organically developed column. In general, it should be noted that the ancient Americans did not have a sense of spatial relations, subtle enough to be able to develop architectural motifs organically. But on the other hand, one ability to cope with huge boulders without levers, without carts, and in Mexico without pack animals, the processing of such boulders with stone tools (bronze is very rare, and the ancient Americans did not know iron at all) in itself is surprising in the study of their buildings. At the same time, it is impossible not to recognize their striving for monumental solemnity, for magnificent magnificence, which was expressed in the decoration of their structures, and undoubtedly very relevant, with relief or pictorial ornaments and images of figures.

Unfortunately, we can judge about the impression that ancient American cities produced in the era of their prosperity only from the stories of contemporary writers, and, due to their very common disagreement, our understanding of these cities, of their greatness and pomp, is very incomplete. From Tenochtitlan, the ancient Mexican capital, built on stilts of the lake, from this American Venice, not a trace remains: its gigantic palaces, decorated with multicolored marble, jasper and porphyry, have disappeared; not even the wreckage of the teocalli, which stood among other shrines, proudly perched on top of a truncated steep pyramid and crowned by the three towers of the temple of the fearsome god of war, Guitslipochtchli, has not survived; Not a trace of such famous floating gardens, fountains and canals has reached us. Only fragments of bare walls, sometimes with embossed images of snakes, indicate the area where the luxurious city once stood out on the terraces of Cusco, the capital of Peru. The sun temple in this city was all inside trimmed with gold and surrounded by walls with a golden frieze; The temple of the moon was all covered with sheets of silver; the walls of the palaces of the Incas, the hall for public parties, schools and monasteries were built with amazing art. In general, it must be admitted that hardly any country in the world has survived as many remnants of the once flourishing cities and villages as in the regions that belonged to ancient American cultural peoples; but these cities flourished, probably not at the same time, but at different times. A particularly characteristic type of buildings in Mexico and Central America is a lagging pyramid with a truncated peak. These pyramids differ sharply from the Egyptian and their external form, completely non-crystalline and non-geometric, and the purpose for which they were built. At least in the Aztec and Mayan tribes they served directly at the foot of the buildings. Temple pyramids were grander than the others, on the upper platform of which there were often only minor buildings with a shrine and an altar for bloody sacrifices. The pyramidal foundations of palaces and public buildings are lagging far below the temple pyramids and immediately expose their official character in relation to the whole structure. In Mexico, on all the large ledges of the pyramid, from each of its four sides, narrow steps went from the bottom to the very top, and sometimes along these ledges only one zigzag staircase led to the upper platform, the Maya usually had one straight, continuous staircase. In any case, the aesthetic and constructive meaning of these ancient American pyramids is quite clear and always the same. Their device was caused by the need to raise small buildings on their own to a height sufficient for them to be visible from afar; the way to build them seems to be the only possible way for peoples with very imperfect technical means to lift significant weights, other than along an inclined plane.

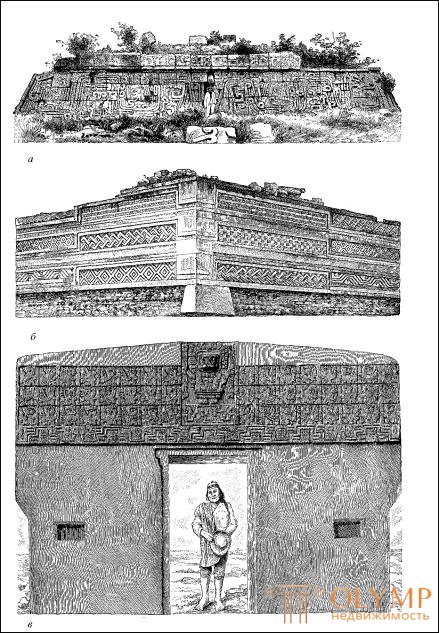

There are about a hundred of similar temple pyramids, which, by the way, cannot always be distinguished from pyramid-fortresses, in Mexico and Central America, of course, only in more or less destroyed condition. To the most ancient and famous in Mexico belong the pyramids in Cholula and the pyramids dedicated to the sun and the moon in Teotihuacan, on the banks of the San Juan River. Particularly majestic is the so-called Thunderbolt in Papantla, rising seven steps to a very considerable height, the teocalli in Guatusco, near Veracruz, and the monument to Hochicalco published by Peñafiel, set on a 120-foot natural basalt base, which had the shape of a truncated cone and artificially pyramid of five ledges. Thus, this monument is represented by a double pyramid. The base of the upper part of the temple itself (fig. 82, a) is a rectangle 24 meters long and 20 meters wide. More interesting and instructive than the construction of this pyramid, its facing on all sides with hard porphyry plates with abundant bas-relief decorations. On the lower ledge from all sides repeats the image of a snake with a gaping maw and a feathered tail. The snake's izviv are stylized so that they stretch along the entire ledge, like a meander, dividing the surface into quadrangular spaces, each of which is decorated alternately with hieroglyphic inscriptions, sometimes with figures of gods and leaders, modeled rather superficially and indefinitely. These figures are depicted sitting on the ground, with their legs crossed crosswise; their heads are dressed in huge, feather-adorned profiles with a profile facing the viewer, while the bodies are en face.

The ruins of the palaces are particularly numerous in the Mayan and southern parts of Central America. Mitla, the pride of Zapotec, Palenque, a Mayan city in Chiapas, Ihmal, Chichen Itza and Sayil on the Yucatan peninsula, the main Mayan country, then Santa Lucia, Copan and Kiringua, on the border of present-day Honduras and Guatemala, are the places of the New World, the richest in majestic ruins.

As for the plan of public buildings in this area, of which some should be recognized undoubtedly by the princely palaces, their dominant form was an equilateral or oblong quadrangle, and only in isolated cases did the building receive the appearance of a round tower. Around the square courtyard there were long and narrow halls, to which, in some places, galleries, like a passage, adjoined.

Fig. 82. Ancient American buildings: a - the pyramid in Chocicalco. From a photo; b - palace in Mitla. From a photo; in - monolithic gate in Tiaguanako (east side). From a plaster cast from the Berlin Museum of Ethnology

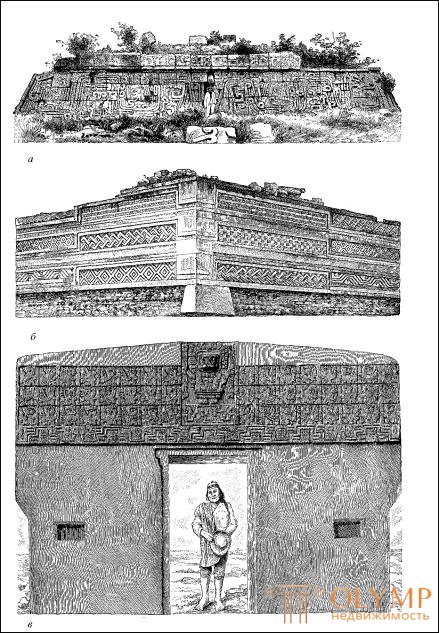

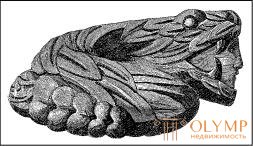

The appearance of the structure depended mainly on a greater or lesser height of its base. That not only temples, but also secular buildings seemed generally pyramidal, evidenced by the so-called castle in Chichen Itza. Frequent in these countries and high-rise buildings; their upper floors have been preserved forever, but preserved, as, for example, on the Yucatan Peninsula, it is enough to recognize the dismemberment of facades in a horizontal direction into three main parts, separated by belts: the foundation, the main surface of the wall and the frieze. Иногда вверху стены встречается еще четвертая часть – сквозная балюстрада, происшедшая, по мнению Малера, от ряда кольев, на которые были натыканы черепа и другие победные трофеи. Иногда эти балюстрады украшены колоннами и полуколоннами, разделяющими их на компартименты. Полуколонны, связанные по три вместе и снабженные внизу, в середине и наверху кольцеобразными утолщениями, расчленяют в вертикальном направлении главную стену в фасаде одного из дворцов в Гунтичмуле на Юкатане, а его фриз состоит из целой колоннады. Лицевая стена гигантского храма-дворца в Сайиле, напротив того, вся заменена рядом толстых, круглых колонн с капителями в виде квадратных плит, так что позади этих колонн образуется открытая галерея. В середине помещено восемь сближенных между собой более тонких колонн с кольцеобразными утолщениями, а над ними, во фризе, – огромное изваяние змеиной головы, превращенное в угловатый орнамент (рис. 83). Разверстая пасть змеи является здесь символом ворот, и вообще надо заметить, что мотив змеиной головы, обыкновенно вычурно орнаментированной и геометрически стилизованной, играет весьма видную роль в украшении дворцовых фасадов на Юкатане. Иногда целые стены сплошь покрыты раскрашенными плоскими штукатурными рельефами, причем поверхность стены в некоторых случаях сначала разделена на несколько полей, а иногда представляет собой только одно поле. Эти поля заняты то квадратными рамками с иероглифическими надписями, то изображениями фигур, то простыми сочетаниями линий, образующих геометрический узор, то геометрически стилизованными символическими фигурами, среди которых преобладает змеиная голова с языком, превращенным в угловатый завиток, напоминающий собой греческий меандр. В Митле стены главного дворца украшены снаружи крупными, орнаментированными наподобие мозаики прямоугольниками (рис. 82, b). In Palenque, the door pillars of the grand palace are decorated with curly bas-reliefs of solid knock painted in red, blue, yellow, black and white. In Uxmal, the middle door of the so-called Governor’s House (Casa del gubernador) is decorated with a god figure in a huge headdress with feathers seated on the throne. in which the meandering stripes alternate with the heads of people and animals (for example, pumas), occasionally there are also motifs of leaves and flowers.

Fig. 83. Sayilsky temple-palace in Yucatan. By Maler

The walls inside the Aztec and Mayan buildings were also ornamented either with whole labyrinths of winding lines or mythological images, most often they were covered with colored plaster and at first, especially in Yucatan, they depicted large paintings on it. In some places the artistic impression was reinforced by columns located inside the hall. Peculiar columns, partly entwined with an ornament composed of feathers, partly carved in the form of primitively numbed but noble-looking human figures, are almost the only remnants of Tula, the oldest city of the Toltecs in the north of their region. In the great hall of the palace in Mitle, parallel to the longitudinal walls of the building are porphyry columns, thinning upwards, without bases and capitals, up to 5 meters high. Remarkable in the abundance of figured ornamentation columns, originating from the so-called Gymnasium in Chichen-Itza.

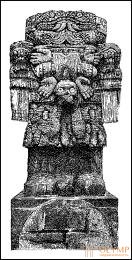

Other structures of these countries, representing the transition from architecture to plastic, namely free-standing pillars and pillars, resembling stone pillars and menhirs of prehistoric Europe, are of a very special character (see Fig. 12). This includes up to 500 pillars left over from the palace in Chichen Itza, round and tetrahedral obelisks in Kirigui, covered on all sides with figures and hieroglyphs, and colossal idols in front of the altars in Copan, on which there is almost no space, not ornamented with images and inscriptions.

In Peru, buildings are generally simpler than in Mexico. Columns and columns are less common, but round constructions are more frequent, the stones of which are hewn according to the required curvature. Inside the buildings, the monotony of the walls is animated by the niches arranged in them; on the outside, on the stone facing of the walls, decorated with inscriptions, there are no surrounding these inscriptions of colored quadrangular frames, which play such a prominent role in the ornamentation of Yucatan constructions. Often, only the gate received plastic decoration.

Peruvian pyramids concessible, located mainly along the seashore, were built to serve as a basis for other buildings not so exclusively as in Mexico, but they also played an independent role. So, for example, the construction of two ledges in Kuslan and the massive pyramid made from unbaked brick in Nepienie is nothing more than gravestone monuments. With less certainty, the same can be said of the giant pyramid near Trujillo, in the land of the ancient lords of Chimu. On the contrary, it is undoubted that only a huge pyramid of 10 ledges in Moche and a crescent-shaped concession in Pachacamac served as temple supports. The huge pyramids in the Santa Valley show how the Incas did with the buildings of the peoples they conquered. They covered up large, brightly painted halls, put on a building outside, so to speak, a cover of unfired brick, and at its top erected a temple to the sun. "In the center of the earth," said Bastian, "the Inca ruled over the world and locked up the deities of the conquered provinces into divine prisons."

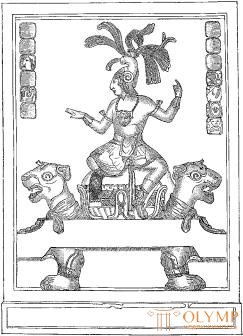

On the inhospitable heights surrounding Lake Titicaca, from the shores of which both the Inca religion and their power over the neighboring tribes began to spread, the ruins of an entire city that existed in previous times survived. These ruins, described by A. Stübel and M. Ole, are located near Tiaguanaco, in present-day Bolivia, at an altitude of almost 4,000 feet above sea level. Researchers distinguish here the remnants of the actual two cities of Ak-Kapana and Puma-Punga. In artistic terms, the monolithic, still quite well-preserved gate in Ak-Kapan, carved from gray volcanic tuff, 3 meters high (see. Fig. 82, c) is interesting. Their western side is a two-story; the middle door and the blind windows in the lower floor are framed with platbands with an extension upwards. The door reaches almost to the top floor, and the frieze separating it from the bottom forms a rectangular projection above the door. The main attraction of the east side is the flat topography decorated with flat relief. Above the frieze, which is a strip of the real meander, interspersed with human heads and figures, is placed a rectangle extending above the frieze, on which is carved a quadrangular stylized figure of God sitting on a throne in a strictly symmetrical pose. On the sides of this rectangle stretched one above the other 3 strips of the frieze, divided into 48 equal squares; all of them are decorated with relief images of winged scepter-bearing creatures; in the lower and upper rows there are human figures, on average, condors with human bodies. The figures are represented in profile, facing the god, who occupies the center of the frieze, and worshiped him. Ole is probably right in suggesting that this scene depicts the worship of the winged geniuses of ancestors, patrons of tribes, the god of heroes Viracocha ... The ruins near Puma-Punga are nothing more than scattered over a large area of debris, architecturally crafted pieces of stone that are amazing , a skillful connection between them.

Fig. 84. Peruvian and Mexican statues. According to Shübel, Ole (a, b) and Peñafiel (c)

The palaces of the Peruvian Incas, from the capitals of which, Cuzco and Cajamarca, still have extensive remains, were often made of clay and then painted white, but also built of properly hewn stone boulders. However, on the terraces and in the palace of Manco Kapak, in Cusco, and in the group of stone houses in the neighborhood of Cajamarca, we also find the so-called cyclopean walls that are not found in Tiaguanaco. Both in the buildings of pre-Inca time and among the Incas, niches are a favorite means of softening the monotony of vast wall spaces. Particularly curious are the niches in the temple of Viracocha, in Kutch, in the terraced walls and the palace of Atagualpa, in Cajamarca.

Sculpture among ancient American cultural nations was in every way as diverse as that of the most artistically mature people: their sculptors worked from all kinds of stone, from precious metals, from copper and bronze, from wood and from baked clay, they knew what bas-relief, high relief and full roundness of the figure; they depicted gods, people, animals, mythological legends and events of history, performed as colossal statues, as well as very small art and craft things; but they lacked the main thing - inner freedom, they lacked a complete understanding of the proportionality of forms in the bodies depicted.

In all the cultural countries of ancient America, both in the north and in the south, we can distinguish four directions when depicting the human body. The first of them prefers a completely conventional, angular styling, leaning toward the shape of a quadrilateral; the second , however, tends to be natural softness and roundness, but usually remains constrained by almost shapeless lethargy; third , setting itself the goal of reproducing individual life, achieves some success only in characterizing heads and faces, and even then only in the more obedient to the artist of clay modeling and metal casting; Fourth, it goes into completely incompatible combinations with anything, caricatures and deliberate deformities. It is not always possible to trace how these directions, developing, followed one after the other in relation to time and place. It is not even unconditionally proven that rough styling into quadrilaterals is the most ancient of the directions. We have already seen in prehistoric and primitive peoples that the image directly observed in nature quite often precedes the geometrization and stylization. For example, it is still doubtful that the two statues that stand out among the many quadrangles that are found in the ruins of Tiaguanaco are more natural and differ in roundness of forms, as some believe, are of late origin. A more reliable measure of antiquity can be considered frontal (according to Lange). In ancient American sculpture, we meet for the first time already with significant deviations from this frontality, and, of course, it can be reasonably argued that the works in which we find such a deviation are younger than others. In this sense, we are, indeed, inclined to recognize the four-sidedly stylized American statues not only always frontal, but also strictly symmetrical in relation to their arms and legs, more ancient than sculptures with live and free movement, the shapes of which in addition are significantly rounded. Earlier than artists perceived images of free body movements in all directions, they apparently went through a stage in which the neck was allowed to rotate only at a right angle to the body. The most ancient symmetry, strictly observed even in the position of arms and legs, is presented to us, for example, sculptural works from Tiaguanaco in Peru (Fig. 84, a); the frontality is reconciled with the position of arms and legs that does not correspond to it in many statues from Palenque (see Fig. 61). A slight deviation from the frontality, shown in a right-angle rotation of the neck, is allowed in the statue of the so-called Chak-Mole, depicting a lying figure found in Chiapas and stored in the National Museum in Mexico City. We see complete disregard of frontality, for example, in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology, in all respects freely and originally conceived, of a sitting man (Fig. 85).

Fig. 85. Ancient American statue. From the original

Fig. 86. Relief from Palenque. By peñafiel

Thus, four-square stylized statues have to be recognized as generally more ancient, and it is quite possible that weaving technique naturally led to this stylization. This seems especially plausible when comparing quadrangular profile figures on the frieze of the large gate in Tiaguanaco with figures on the fabric from the necropolis in Ancona published by Stuubel. One can hardly be considered a step forward towards greater freedom of image, in which among the quadrilateral forms there is occasionally a round eye or a rounded outline of the chin (Fig. 84, b). We notice a little more freedom only in those images which, like the statue of the so-called Goddess of maize, a museum in Mexico City (Fig. 84, c), appear to be four-sidedly stylized due to the angularity not so much of body shape, but of clothing, especially a huge rectangular headdress.

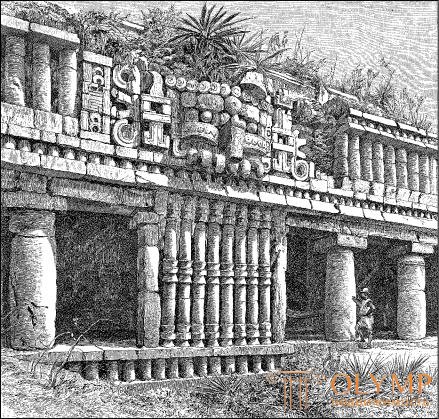

The direction of the softer, striving for greater roundness, includes many of the statues of our museums and many of the sculptures and reliefs of the Middle American, especially Yucatan buildings. But within this direction one can discern several separate currents. For example, statues and reliefs from Palenque (fig. 86) are typical. More correct than here, the proportions of the body, we never find anywhere in the ancient American images of man. In all the sculptures originating from Palenque, the Indian type is clearly pronounced with a characteristic arched aquiline nose, a type obviously evident in the Mayan tribe. Perspective difficulties in reliefs are not so schematically incorrectly resolved as in Egyptian art. But here, too, individual figures should be recognized as apparently more ancient, and frozen in conditional immobility - later. One of the most peculiar and lively images is the relief, representing the scene of the sacrifice to the god Kukulkan, originating from the Maya area inhabited by the British Museum. In this relief, a typical image of heads is combined with an angular stylization of clothing (Fig. 87). The human figures of the original reliefs from Santa Lucía Cosumagualpa (in Guatemala), published by Dr. Gabel and trapped in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology, are incomprehensible, but still freer, more relaxed in the movements. Soft and natural as a whole, but in the modeling of individual parts the Atlanteans from Punta del Zapote, in Nicaragua, are rough and poorly understood, published by Beauvelius. Works that attempt to portray pure beauty are extremely rare; but they include the amazing human head in the mouth of the highly stylized Chiguacoatl serpent (a very common mythological image) from Tula (Fig. 88), characterized by almost classical freedom and regularity of facial features.

Fig. 87. Sacrifice to God Kukulkan

Fig. 88. The human head is in the mouth of a snake. Sculpture from Tula. By peñafiel

Among the most characteristic stone sculptures are the heads from Pantaleon, in Guatemala, published by Gustav Eisen; but most characteristic of all is the above-mentioned figure of an old man (see fig. 85), striking with the easiness of inclination of the upper part of the body. In this figure there is not the slightest sign of frontality. The old man sits on the ground, knees apart; the shape of his skinny body is as typically Indian as the features of a wrinkled face.

In various museums, there are also small metal cast, very lively figures, such as, for example, a massive silver, unfortunately rather heavily damaged figurine from Cusco, which is kept in the Braunschweig Museum. She depicts a dwarf in a pointed cap, with a smiling face and a wart on her right cheek. But human heads, having an individual character, are most often found in ancient American clay products. In every significant ethnographic collection one can find clay figurines with characteristic expressive faces; these are idols, images of ancestors or even nothing more than children's toys originating from various parts of ancient America. Ole published two wonderful clay male figurines from Yucatan, located in the Berlin Museum. One depicts a Mayan chief in full feather dress, and the other, preserved only in its upper part, represents a sample of a noble and full life of a person with a tattoo. In particular, finely executed, often even meaningful facial expressions are often found, with human heads on earthen vessels, found in large numbers in Mexico and Peru. Pottery art of the inhabitants of these countries was manifested mainly in the facial urns of various kinds. Ancient America is a classical country of vessels, which usually represent the human head in their upper or middle part, and often reproduce themselves and the entire human figure as a whole. The National Museum in Mexico City abounds in similar vessels found in the land of ancient Aztecs. The British Museum, the Berlin Ethnographic Museum and the National Museum in Lima are especially rich in the same vessels found on the Peruvian shores. On the upper part of the Recuisky vessels in the Berlin Museum even whole scenes made up of small figures are depicted. The weak development of forms is noticed in the hollow clay figures of the Chibcha tribe in the same collection with their wrinkled bodies and completely monotonous openings of mouths and eyes.

Fig. 89. Colossal statue of Coatlicue. By peñafiel

The pursuit of monstrous, ugly, caricature is expressed in so many ancient American sculptural works that it is enough to point to the colossal statue of Coatlicue depicted by Peñafiel in the National Museum in Mexico City (Fig. 89). The middle of this shapeless monster, a semi-amphibian-half-man, is occupied by a skull. Skulls in general are not uncommon in plastic images of these peoples, which is not surprising when their cult of skulls are caused by human sacrifices.

Images of animals from American cultural nations were usually more typical than individual; however, for the rest, they, like the images of a person, are different in style. The golden turtle - an amulet in one private collection in Mexico City - represents a sample of a particular style. The stone turtle in the Christie collection, in London, for all its naturalness, is

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)