The middle kingdom is a period during which Egypt rose again, coming out victorious from long and difficult trials, and there followed a revival of all the arts on the banks of the Nile irrigated with sacred waters. This period was at times classical writing and the new flourishing of the fine arts based on that created in the Old Kingdom. This peak reached its peak during the 12th dynasty.

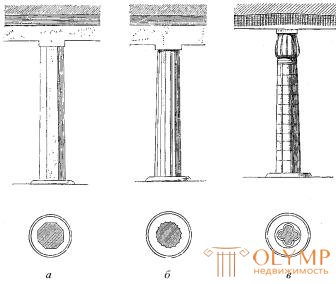

The best preserved monuments in this period are tombs. The tombs of the kings continue to serve as pyramids, such as the pyramids of Uzertesen II in Illagun, Amenham couple II in Gavar and Morgan-studied pyramids in Dashur, made of black brick and lined with large blocks of white limestone. The reduced use of the pyramid motif can be seen in the small brick pyramids of Abydos, the holy city of the dead Osiris, where at that time every wealthy middle-class man built his own tomb or at least set a gravestone for himself. As a rule, erected on a square foundation, with a burial chamber covered with a false vault, plastered and painted, these pyramids have a different look than smooth large royal pyramids. But the sovereign princes and members of the upper class preferred to be buried in caves carved into the rocks on the home side. The most famous of these grave caves are in Beni Hassan, in Bersh, and in Sioute, in Central Egypt. The whole grave is hollowed out in the rock. Usually it consists of a portico, the arch of the entrance to which is supported by pillars or columns, from a memorial dormitory, where a niche with a statue of the deceased is sometimes placed, and from a secret crypt for a sarcophagus, where the shaft-like passage leads. For the history of architecture, the cave tombs of Beni Hassan are especially important, because at the backwaters of their porticoes and memorial chambers it is possible to trace the further development of the style of Egyptian stone buildings. Straight, tetrahedral columns of the Old Kingdom are replaced first with 8-sided (Fig. 121, a), and then with 16-sided. When smooth troughs (flutes) are carved out on 16 faces, the so-called protodoric column (b) is obtained .

Fig. 121. The development of the Egyptian column in the era of the Middle Kingdom. By Perrot and Shipie

The round plinth (base) and the square plate of the tire (abacus) reinforce the impression of such a column, carefully carved out of stone. At the same time, already composite columns appear with capitals in the form of unrevealed lotus flowers (c). Their stem is made of four convex stems, intercepted by hoops at the top, where a small capital stands, which also consists of four unblown lotus buds, first diverging apart and then tapering. The round base and quadrangular plate of the abacus, on which the architraves rest, complete the column. Lotus-shaped columns with cup-shaped capitals in the Middle Kingdom are very rare. Borchardt found a sample of such a column in a painting of one of the tombs in Bersh. The lily, or capital in the form of a blossoming flower, is depicted on the throne of the statue of Uzertesen I, the Berlin Museum. Columns composed of several stems of papyrus, with capitals in the form of unopened flowers appear in the middle period quite often. The most complete development of their are stone columns of the temple at the pyramid in Gavar. Capitals in the form of blooming papyrus flowers are found in the Middle Kingdom, except for a small stone column with a distinct 3-sided stem from Kagun, mainly in the images on the walls of the tombs. The first classic example of a palm-shaped column is in one of the tombs in Bersh. In the ruins of temples, we have seen a special kind of capital, in which, from two or four sides, the head of the goddess Gator is depicted in relief in a huge headdress and with sharp cow ears.

Flat images on the walls of the cave tombs of this time acquaint us with the life and art of the Nile Valley. In Beni Hassan, we already see not only painted reliefs, but also real wall paintings, not frescoes, but paintings but tempera in the broadest sense, the colors of which, diluted with gummitraganth water, were superimposed with the help of a reed stalk or hair brush. The content of these paintings is generally similar to the plots of the tomb images of the Old Kingdom, but here and there drawings are mixed with them that glorify the deceased's actions: hikes, battles, siege of fortresses, mixed with idyllic scenes of villagers life, hunters and fishermen, or cute scenes of life and work are depicted artists. The language of these images is generally the same as in the Old Kingdom, although human figures become somewhat more slender and tall, and the story is clearer and more alive than before; poses are less forced, and in isolated cases, through the traditional immobility of Egyptian art, as if lurking the desire for a more correct and free placement of figures. Finally, agricultural implements begin to play a prominent role. Images of gardens with a strange mixture of plans and vertical projections are often taken, apparently, regardless of the plot. Palm trees, fruit trees, vines, cypress trees are depicted distinctly and naturally.

Purely ornamental motifs in the Middle Kingdom also become more diverse; The quatrefoil, probably a geometrical prototype of a floral rosette, appears both separately and in plexuses. But the greatest development in this respect is achieved only in the New Kingdom.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.6 people play!

Play gameGame: Perform tasks and rest cool.6 people play!

Play game

Fig. 122. Heliopolis obelisk near Cairo. From the photo

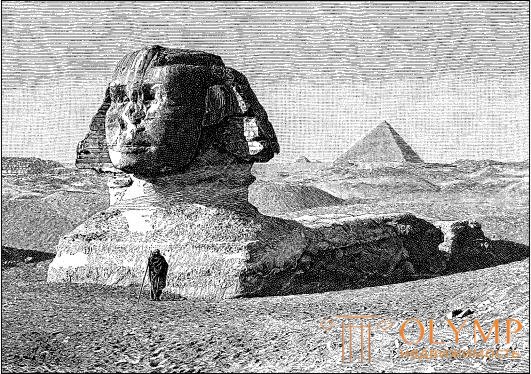

Of the surviving sculptural works of the Middle Kingdom should be put on the forefront of the statue of the pharaohs, usually excised from black or gray granite or from diorite. Of the hard stone rocks, it was preferred at that time not dark and pink, but dark. In the statues, as in the images on the plane, there is no noticeable success with regard to the freedom of the motives of movement, but, according to the taste of the era, there is an elongated proportion. The shoulders are wider than before; Compared with the constricted camp, the neck is thinner and stretched, the legs are extended, the muscles are outlined weaker. The facial features, while preserving the portrait likeness, to which artists had sought before, approach the same Egyptian ideal of beauty. Be that as it may, the 12th dynasty of the Pharaohs did not have a beautiful appearance: outstanding cheekbones, a sloping forehead, a wide mouth gave a flat face a type like Slavic, perhaps even African, and even idealized heads of royal statues disfigured. To verify this, it is enough to look at the Berlin Museum at the colossal statue of black granite, depicting Uzeterzen I and originating from the Abydos temple, and at the black granite statue of Nofrit, the spouse of Utertesen II, the Museum of Giza (Fig. 123).

Fig. 123. Granite statue of Nofrit. From the photo of Brugsch

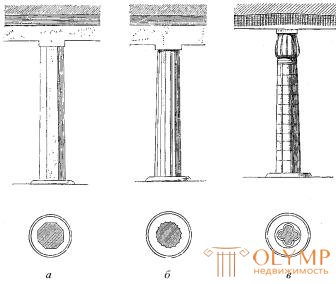

From the time of Borchardt’s research, the image of the pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom is also a colossal sphinx at Giza, which was previously considered the most important work of Egyptian sculpture, created to serve as a model for eternal times (Fig. 124). On a lion's body, which for a long time remained covered by shoulders in the sand of the desert, then dug out and again covered with sand, the king’s stone head, carved out of a whole rock and facing the east, with eyes wide open and with an eternal smile rises 20 meters from the base. mouth. The artists of Amenemhet III returned to their former realism; the sculptural type of the dynasty of this Pharaoh so embodied in his famous heads that for a long time the statues of this king and lion's sphinx with the same head were considered to be the work of foreigners, probably geeks, who kept Egypt under their yoke between the middle and new periods. However, Golenishchev proved that these are the heads of Amenemhet III and that, as such, they should be considered the most typical among the heads of kings of the 12th dynasty. The black granite sphinx with its head, especially low protruding from the mighty lion's mane, and a fragment of the same royal statue of gray granite are in the Museum of Giza; similar figures are available in other collections. But in the flattered youthful beauty of a purely Egyptian type, a naked, gilded, wooden statue of King Gore appears before us, brought to the Museum of Giza from the Dashuri southern brick pyramid. In this statue, all the flattery was shown, with which Egyptian artists smoothed the unpleasant features of their physiognomy in portraits (Fig. 125). Besides the kind of works belongs to a pretty little wooden figure of Metukhotep, the Berlin Museum. She lay in the coffin of the depicted king, on his mummy. The long cloak is made of white and the body is made of brown wood. The hair was dyed blue, and the eyes were natural. Further, it is necessary to mention the bloated, smiling, lifeless colossi of the 13th dynasty, such as, for example, a statue of pink granite in the Louvre Museum, in Paris, depicting King Sebechotep III sitting on a throne. Such works have no significance for studying the history of the development of Egyptian art and represent only such features that have been inherent in him at all times.

Fig. 124. Sphinx in Giza. With photos Plyushova

Among the artistic and industrial works of the Middle Kingdom, products of goldsmiths deserve attention, such as, for example, the luxurious costume of Princess Gator-Sat (12th dynasty), found by Morgan in the northern Dashur pyramid. Particularly remarkable are the golden breastplates in the form of light-colored small temples, covered with red, light blue and dark blue enamel, representing skillful through work in a pure and rich heraldic style. They belong to the Giza Museum (Fig. 126). From the same time, separate carved stones were preserved, mostly in the form of scarabs (beetles). These stones were inserted into rings and served as seals, like cylinders used in Mesopotamia during the first dynasties of Egyptian history. The Louvre owns such a ring since Amenemhet III; on the sardonyx inserted into it is very finely carved with a deep relief on the one hand the seated owner of the ring, and on the other the king who plunges his enemy to the ground.

Fig. 125. Statue of King Gore. By morgan

Ceramics. Potters, who used potter's wheel for a long time, made significant progress compared to the ancient period. Particularly noteworthy are the vessels of various shapes with geometric ornaments, inscribed with white paint on a red background or red-brown on yellow or white. The figures of animals and people, here and there interrupting the pattern, can hardly be recognized. It can be seen that the pottery did not have any relations with Benihassan painters. Along with these vessels, glazed pots (the so-called Egyptian porcelain) have a price of mostly turquoise or azure color. Animal figures were also made of glazed clay. One of these figures, kept in the Museum of Giza, is a blue hippo among marsh plants painted black.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.6 people play!

Play gameGame: Perform tasks and rest cool.6 people play!

Play game

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)