In the IV. the development of Greek art went along the path laid, initially regardless of the events of world history. The path to artistic truth, going from severity and elevation as from the starting points, was in the V c. in the fields of the purest and most perfect beauty; now he turns into blooming areas of pretty and sensually charming. As far as the tendency to the typical allows, which now, as before, still prevails in Greek art, freer and individual features begin to erupt everywhere. Next to art, serving certain religious or social purposes, pious remembrance of the dead, or alleviating emotional distress through sacrifices and initiations, there is almost completely unknown art for art, which is gradually, almost imperceptibly, more and more brought to the fore.

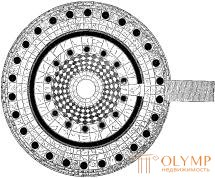

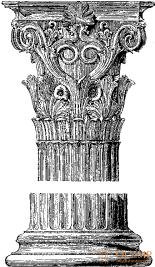

Architecture IV. everywhere creates more luxurious, original buildings and more free forms. The Doric style gives up its leading role, but does not fade away and does not stop in one place, but continues to develop in the direction indicated above, deviating more and more from its fundamental, stubbornly courageous character. The Temple of the Mother of the Gods (Metroon) on the hill of Kronos in Olympia belongs to the first half of the 4th century. The capitals of its Doric columns with 20 flutes have, under the echin, instead of a ring, a recess in which, perhaps, a metal strip was placed. The small temple of Asclepius in the healing place of Epidaurus also refers to the first half of the 4th century. His cella, unusually ending at the back of a smooth wall, stood inside the colonnade, formed by Doric columns also with 20 flutes. The famous temple of Athena Alei in Tegea, the project of which is attributed to the great sculptor Skopas, was a Doric peripter only from the outside; his cella was divided into 3 ships with ionic columns, and the portico was decorated, apparently, with Corinthian columns. In the middle of the 4th century, a large temple of Apollo on Delos was built, which was the common sanctuary of all Hellenes, and the temple of Zeus in Nemea, which was considered to be the sanctuary of the Peloponnesians. These temples, like the three above, belonged to the Doric and had 6 columns in their short sides. Regarding the individual forms of all these buildings, we can say what R. Borrmann said about the details of Leonidaeon in Olympia: "The straight form of Ekhin, the insignificant height of capitals (one third of the diameter of the upper section of the column), the low entablature, the architra of which is less than a frieze, narrow plates with drops, - all these are signs of the decline of the Doric style. " Leonidae - a building erected in the second half of the IV. Naxos Leonid, in all likelihood, for accommodating honored guests and holiday embassies, was one of the most significant private buildings in ancient Greece. The columns of the galleries surrounding the large square courtyard of this building were Doric; from the outside it was decorated with a colonnade of Ionic style. We also find the combination of Doric and Ionic styles in one Peloponnesian building of a peculiar form; this is Folos in Epidaurus - the round hall, whose builder is Policlet the Younger (fig. 379) According to Derpfeld, Folos was surrounded on the outside by 26 Doric columns, and inside contained 14 Corinthians with highly developed capitals (see Fig. 315). The building was built at the end of the IV century. The Doric style and the Peloponnese found a random use even in Asia Minor, such as, for example, in the temple of Athena Polias in Pergamum; but now the Peloponnesian peninsula has become its main distribution area.

Fig. 379. Plan Folosa in Epidaurus. By durpfeld

Ionic style in the IV. He won new victories, while Corinthian did not dare to appear in the outer colonnade of temples, except for small buildings of this kind, and found himself only inside. The most diverse forms of the Ionic style are preserved in the facades of Lycian tombs carved into the rocks belonging to the considered era, such as, for example, in Telmesse, in Antifellos, in the World. The ancient Veliky carpentry style with which we have become acquainted (see Fig. 231) gives way here to a simple Ionic gable facade, usually with only two columns (Fig. 380); These facades are especially important for us because in them we find various Ionic forms that should be looked at both as remnants of the more ancient stages of development, and as the further development of the style in a roundabout way. The frieze here for the most part does not exist, so a row of dentils is placed directly above the architrave, which consists of three lanes all the time. The bases of the columns, often completely smooth, often have a simple chute between two shafts, which are commonly called attic. Capitals represent archaistic or loosely composed forms.

Fig. 380. Ionian facade of one of the Lycian mountain tombs. By von Siebel

In the actual Ionic Asia Minor, the construction of the Branhid Shrine, a large, luxurious temple in Didim, near Miletus, continued. The temple of Athena Polias in Priene was re-erected, consecrated, as legend says, by Alexander the Great in 340 BC. e. His builder Pythia Vitruvius was considered one of the most notorious opponents of the Doric style. The columns of this temple, which has come down to us in the form of a pile of ruins, are often referred to as the traditional developed Ionic style (see. Fig. 258). Pythyus, along with Satire, is also considered the builder of the Halicarná Mausoleum, the majestic tomb of King Mausolus, who died in 351. The mausoleum, which became the nominal name of the luxurious royal tombs, is a further development of the Nereid Monument and at the same time the ideal transformation of ancient tombstones found in this area. He had an almost square plan; a massive structure of slabs rose above its low base, above which stood a gravestone temple surrounded by a colonnade (9411 Ionic columns) with capitals with small volutes. Its roof consisted of a truncated marble pyramid of 24 ledges, on the upper base of which was placed a quadriga with colossal statues of the king and queen. With the construction of a new temple of Artemis in Ephesus, in the place burned in 356, the name of Deinocrates, the Greek architect of the times of Alexander the Great, is connected with Gerostrat. This temple was built according to the same plan as the old temple of Khersifron, but its forms, according to the new time, were more free. The slender columns were again "columnae caelatae"; their lower part above a multi-component base was clad in a veneer decorated with plastic pieces; but this expensive sculpture (fig. 381), depicting the return of Alkesta from the underworld, in comparison with the sculpture of the former church, was made in a freer style of the 4th century. In general, Daynocrat was mainly involved in drawing up city plans. He owned the plan of the city of Alexandria in Lower Egypt. Deinocrat’s deep wit and courage of fantasy were expressed especially in his project of turning Mount Athos (1935 meters) into a figure of a giant holding the whole city in one hand and a vessel from which all the waters of the mountain would pour into the sea. Hermogenes, also considered among the resolute opponents of the Doric style, lived somewhat later. His temple of Artemis Levkofrina in Magnesia on Meander Strabo called the sanctuary, "which in its abundance and richness of the vows of gifts although closely approached the Temple of Ephesus, but far surpassed it by proportion and the art of the arrangement of parts." Excavations proved that it was a pseudo-dipter, standing on a five-stage platform. The frieze adorning it is in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Fig. 381. Relief of one of the columns of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus. From the photo

Along with these Ionic temples, it is necessary to mention the round construction of the same style, the Philippión in Olympia (Fig. 382). It was erected by King Philip between 337 and 334. and represented, in the words of Adler, "the true child of his age." The round building, which stood on a three-stage base, was surrounded by 18 Ionic columns. Cella was taller than this colonnade; its wall, divided into two floors, was divided by 9 Corinthian columns. Another round building, smaller, is the oldest one decorated with Corinthian columns outside, or rather, columns, a quarter of which goes into the wall; in fact, this is nothing more than a monumental base for a tripod in the Athens "Tripod Street", decorated with votive offerings to winners in dramatic competitions, the so-called Lysicrates religious monument, consecrated in 334 (Fig. 383). On the six incomplete columns, leaning against a round stone cylinder, there is an ordinary entablature: a three-lane architrave, a frieze decorated with sculptural images, a crown with denticules and a cornice on which a tent-shaped scaly roof rests. The acanthoic extension on the top of the roof, which served as the base for the tripod, is completely in the spirit of the Corinthian style. Corinthian capitals with their lower rows of leaves, like reed, are even more free-standing than later Corinthian capitals (Fig. 384).

Fig. 382. Olympic Philippine in section. On the restoration of Adler

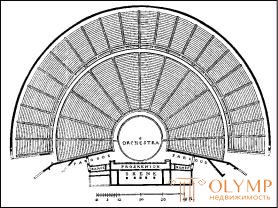

The further development of Greek theatrical architecture was expressed in the 4th century by the construction of stone buildings for spectators and stone scenes everywhere. Usually, a round orchestra, to which the stage adjoined in tangent, was separated from the room for the spectators by a passage in which they conducted either a road or a canal with water. On the sides of the front wall of the theater they walked in the form of wings of paraskenia, between which was placed a movable wall of prosperity, which served to hang decorations on it. This stage of development belonged to the Athenian theater of Dionysus in the form in which it was completed during the reign of Lycurgus (338-326). From this theater, seats for spectators with their three rows of seats (Fig. 385), with thirteen aisles and marble thrones for honored visitors have survived to some extent; the throne for the priest of Dionysus, decorated with reliefs, was a miracle of Greek applied art. Further, the theater in Epidaurus (Fig. 386) was considered a model building - a work, like the aforementioned Folos, Poliklet the Younger. According to Derpfeld, therefore recognizing the existence of a second, younger Policlet, the Epidaurus Theater was built later than 330, perhaps even at the beginning of the 3rd century. The seats for the spectators were arranged in two rows, with the lower row divided into 12 wedges, and the upper into 22. In front of the large hall, divided inside into two naves, we find here for the first time a stone wall of prosperity, decorated with Ionic half-columns. Near the prospection, there are holes for the installation of rotating tripartite decorations, periact. IV century also belongs to the main part of the most extensive of the theaters of Greece - the theater in Megalopol in Arcadia. His hall, which was 66 meters long and 52 wide, was Fersilion Pausanias, opened to a portico appointed to the audience; this room was a hall connected to the theater, in which there were space for standing people from the sides and a series of slender columns were radiating.

Fig. 383. The religious monument of Lysicrates in Athens. From photo of Romaides

Greek art of the fourth century laid out new ways for itself.

Only now she has reached the height that is possible with the full possession of technical means, with the mastery of all sorts of positions and motives, with the ability to transmit any kind of spiritual movements. What was possible to express the plasticity of the next centuries to come was largely prepared by the painting of the fourth century; but one, at least of the latter’s schools, in turn, was influenced by the sculpture that was ahead of it, namely, Scyonian, which became the head of the new direction.

Fig. 384. Corinthian capital of the monument Lysicrates. According to Michaelis

Fig. 385. Marble seats of the Theater of Dionysus in Athens. According to Derpfeld and Reish

As we have already seen (see Fig. 366), the Sikion school attached the main importance to the computable relations, the doctrines capable of developing further, the purity and correctness of forms. The first painter of this trend (chrestografii) was Evpomp. One of the ancient frescoes in the Palazzo Rospiglios in Rome, "The winner with a palm branch in his hand," perhaps, is a reflection of the work of this artist. A pupil of Evpompa Pamphil, the head of the Sikyon trend, defended the teachings of this school in literature and introduced teaching drawing to Greek schools. We know more about his teaching activities than about his works of art. For his course of study, which lasted 12 years, he took on one talent (4,000 marks). Professionals and artists flocked to his school. The great Apelles himself graduated from her education. One of the most important achievements of Pamphilus is the improvement of the technique of encaustic wax painting. Since the time of Donner von Richter's research, we know that, in this kind of painting, multicolored wax pastes were superimposed on wood or ivory plates with the help of a kestron, a metal tool similar to a spatula, and then processed, at the end of the painting on its surface were heated with iron core; this heating (kausis) acted as a light varnishing, and due to the weak melting of the wax, the individual paints gently merged at their edges with each other. Compared with the then common painting of a tempera, the encaustic wax reached a greater brightness of color, but was laborious, required painstaking work, and therefore was used only for the execution of small paintings.

The pupil Pamphilus Pavzii was the first to make a name for himself as regards the techniques of this kind of paintings. The image he wrote to his beloved flower girl Glykera enjoyed loud fame; even more was known his "Sacrifice of the Bull", in which the bull was presented visible from the front, in full perspective; but the greatest glory was enjoyed by the painting in the round building in Epidaurus, which depicted the god of love and beside him “Drunkenness” in the form of a figure drinking from a glass vessel. The face of this figure was visible through the transparent vessel. All this was new for that era and testified to the success of technology, which depended on the properties of encaustic wax painting.

Fig. 386. The plan of the theater in Epidaurus. According to Derpfeld and Reish

Pedagogical activity of Pamphilus was continued by his pupil Melanthus, who wrote the tyrant Aristratos with his quadriga. It is said that the great comrade of this master in teaching by Pamphile Apelles voluntarily ceded his right to a prize in the competition for the performance of this painting.

The second Greek school of the 4th century is called Thebes , because it originated in Thebes in the era of short-term prosperity of this city, or Theban-Attic, because it soon moved from Thebes to Athens, or, finally, without any basis, the younger Attic. Apparently, this school has set itself the task, in contrast to the somewhat numbed idealism of the Sikyon forms, their more relaxed handling and greater vitality in the transmission of sensations. At the head of this school is usually put or Aristide, or Nikomakha, depending on who of them is considered its founder. In our opinion, Aristide is more likely to recognize them. The Theban Nikomakh, apparently, wrote mostly mythological plots and was famous for the ease and tidiness of his brush. On the contrary, Pliny the Elder praises Aristide as a master of portraying strong feelings, especially pathetic emotional distress. In one of his paintings, which represented the capture of the city, a dying woman was painted, the child of which, much to her despair, asks for her breasts. Among his works were “The Sick”, who deserved endless praise, “Begging,” written so truthfully that it seemed as if his voice was heard, and the figure of a woman hanging out of love for her brother. The third most remarkable artist of the school in question was Evfranor from Corinth, who studied in Thebes from Aristide the Elder, whom we consider to be a sculptor, not a painter; apparently he worked in Athens. Evfranor was as famous as a sculptor as he was a painter. Three of his most important paintings adorned standing in ceramics in Athens. The middle picture depicted the cavalry battle of Mantinea, and the pictures on the narrow walls were represented by one 12 gods, the other - a symbolic plot: the hero Theseus, who leads "Democracy" as a woman to "Demos", the personification of the Attic people. As far as the direction of Evfranor was considered even more ancient than the direction of Parrazius, it can be judged by the ingenious remark of Pliny the Elder: "Theseus Evfranora ate meat, and Theseus Parazia - roses."

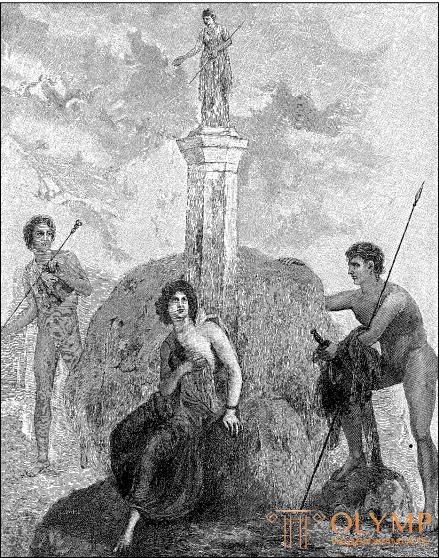

The place of activity of the students of Euphranor was Athens. Nikiy, so to speak, his artistic grandson, was at that time the chief Attic master.The great sculptor Praxitel especially appreciated those of his statues that Nicius supplied circumlitio (in the words of Pliny), that is, coloring. According to Pliny, Nicias carefully observed the effects of light and shadows, and most of all he was concerned that his figures had relief. He painted large pictures with tempera, and smaller ones - in an encaustic way, and spoke out against the depiction of small objects like flowers, fruits, etc., which were in great deal with him, and, apparently, hinted at Pavzia. He himself considered only important subjects worthy of art. His painting depicting Io, which Argus guards and frees Hermes, is believed to have been copied, of course only approximately, by some ancient wall paintings preserved in Italy; the most remarkable of them is on the Palatine in Rome (fig. 387).Among the works of Nikia Pliny the Elder called a portrait of Alexander the Great. So the name of Alexander first appears in the history of art. The most gifted people looked at him not only as a conqueror, but also as a unifier of the Greeks, who led them to new victories; artists glorified him and put themselves at his disposal.

Fig. 387. Io, Argus and Mercury. Fresco found on the Palatine Hill in Rome; work, probably Nikia. From the photo

Fig. 388. Battle of Alexander the Great with Darius. Mosaic. With photos Alinari

However, the portrait of Alexander is mentioned among the works of another master of the Theban-Attic school. This master is Filoxen, the disciple of the Nicomechus whom we have put at the head of this school. Pliny the Elder counted among his works, which did not have similar ones - written by Tsar Cassandra (about 300 BC) image of the battle between Alexander and Darius, in other words - the battle of Issus. This work is important to us, as we, together with Michaelis, see in it, and not in the Battle of Issus, the dubious Egyptian artist Helena, the original of the large mosaic picture found in Casa de Fauno in Pompeii and transferred from there to the Neapolitan Museum (Fig. 388). Among the surviving works of ancient art this mosaic belongs to a very prominent place as a battle of the picture with figures in full size. It depicts a historical moment when Darius nearly fell into the hands of the Macedonians, led by Alexander, he escaped thanks to the fact that one of his entourage gave him his horse. In the very middle of the picture, in the foreground, the Persian is already keeping the horse, which is presented backwards to the viewer, in a bold perspective. The king still stands on his chariot, thinking not so much about his salvation as about his people, with a gesture of despair he turned to the Persian leader, who, already overtaken by Alexander’s spear, falls to the ground with his horse. Fortunately, it was the upper part of the figure of Alexander, with her stately, energetic head that had lost its helmet, and was preserved quite well. In general, in this picture, due to the need to depict the height of the fight, there is no mention of any observance of the conditions for the distribution of figures in the depths of space. Some rigidity and irregularity of the picture may have come from reworking the picture into a mosaic image, but in general this work remains an example of the transfer of a horse-drawn battle with a striking central dramatic episode; the expression of deep sorrow and suffering on the faces of the vanquished and the calm, triumphant grandeur of Alexander's face is clearer than all that remained of the painting of a distant era, testify to what progress she made around 330 BC. e.

Fig. 389. Odysseus learns Achilles. Perhaps a copy of the picture of Athenion. With photos Alinari

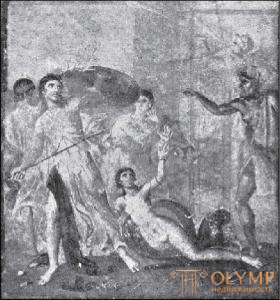

Finally, another master who worked in Athens, although he was a native of Thrace, Afhenion from Maronei belonged to the Theban-Athenian school. Pliny the Elder said that he was as much respected as Nikiya, and sometimes they put him even higher. He is important to us, since among his works was a painting depicting Achilles in women's clothes, recognized by Odyssey among the daughters of Tsar Lycomed; various repetitions of this plot, the original of which could belong to Afenion, are preserved among the Pompeian wall painting (Fig. 389).

Here we can take a place also Timomakh from Byzantium, which belongs to the number of outstanding ancient painters. According to Pliny, he lived in the time of Julius Caesar, and the researcher Robert supported this tradition. However, Welker and Brunn argued that Pliny was mistaken in this case, that Julius Caesar only bought two main works of Timomakh, Medea and Ajax, and brought them to the temple of Venus Genetrix and that during Cicero they were in Kizik. Brunn, for this reason, did not consider it possible to relate the activity of Timomach further than to the era of Nykomaha, Apelles and Aristide, as later writers spoke about him with these masters. Lyoshke carried it not even to the end, but to the beginning of the IV c. However, the arguments of Brunn seem to us the most convincing. The main works of Timomakh are Medusa Gorgon, Fury of Orestes, Medea before the killing of their children and Ajax after their fury. Numerous epigrams, glorifying these works, noted in them the transfer of fluctuating spiritual moods. The image of Medea found an echo, perhaps in some Campanian wall paintings. Thus, Timomakh is a master, inspired by the plots drawn from the Athenian tragedy, and he, perhaps, more than any Greek painter, the main role played by spiritual pathos, the opposite of the physical pathos of Aristide.

The mentioned artists are followed by great masters of the 4th century, who are usually united in one Ionic school and who, in any case, can be considered representatives of the overseas school of the time in question, since they were all natives of countries lying on the other side of the Aegean Sea. At the head of these masters should be put Apelles, recognized as the greatest painter in the world, not only by all of the later ancient history, not only medieval Christianity, but also the era of the European Renaissance. In the language of art lovers and connoisseurs, to be the Apelles of any people, until recently, was to be the greatest painter of this people. Apelles was a true Asia Minor. He was probably born in Colophon, but received citizenship rights in Ephesus, and therefore is considered an ephesus. In an effort to connect his innate Ionic lightness with Doric thoroughness, he attended Pamphilus School in Sicyon. From the very beginning of his independent activity, he entered into proximity with the Macedonian royal court. Even King Philip invited him to his capital, Pella, where a circle of court artists had already begun to form; the orders that these artists had to perform were purely monarchical: it was necessary to exalt the personality and deeds of the king, his generals and dignitaries. Therefore, the paintings performed by Apelles during the first time of his activity, mainly portraits, belonged to this realistically courtly direction and had historical significance, of course, due to the importance of the depicted persons. Pliny the Elder said that it is difficult to calculate how many times Apelles painted portraits of Alexander in the image of Zeus, with Perun in his hand (in the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus), Alexander the peacemaker in the triumphal chariot followed by the War in fetters, Alexander the commander on horseback, written so naturally that the horses laugh at the sight of him. In this kind of paintings by Apelles we meet for the first time with this portrait painting of a high historical style.

When Alexander left Pella, marching against the original enemies of Greece, the Persians, Apelles, apparently, moved to Ephesus. After the death of Alexander, he traveled to Alexandria to the court of King Ptolemy, which the artist’s rivals interpreted to the wrong side, which gave him a reason to write an allegorical picture of “Slander”. She was so much praised by Lucian that the artists of the Renaissance Botticelli and Dürer tried, based on her description, to restore it with their brush. Without a doubt, such a symbolic image, representing the embodiment of an abstract concept in human images and penetrated by the outer and inner life, was unthinkable at the earlier stages of the development of Greek art. The famous mythological paintings of Apelles relate mostly to the later period of his activity. Poets chanted them, art writers glorified them. Aphrodite Anadiomena, the goddess of love, coming out of the sea and squeezing saline moisture out of her hair, was most famous for him. This painting, written for the island of Kos, was subsequently transported to Rome; she enjoyed loud fame as one of the finest works of art. Her motive has reached us in many sculptural works. The last work of Apelles, his second Aphrodite, who was on the Spit and remained unfinished, according to the testimony of ancient authors, was so beautiful that no one dared to finish it. It can be assumed that Apelles died on the Spit. The novelty of his mythological paintings was in their intention. According to the contemporaries of the artist, they were distinguished by inimitable ease of execution and grace — qualities that were generally valued in them mainly. The painting of Apelles was quite the brainchild of his time; she no longer amazed the viewer with her severity and grandeur, but chained herself with naturalness and freshness, fascinated with her charm and originality. Technically, the art of Apelles probably reached the perfection that was possible for Greek art. From the technical innovations of this master point to the invention of paint; perhaps, in part, the dazzling impression that the effects of lighting and paints made in the paintings of Apelles depended in part on its use. But, according to many, his main advantage was that he knew how to stop work on the picture in time. His favorite saying was: "Manum de tabula".

The most important of Apelles' rivals, and at the same time his friend and protégé, was Protogen, who set up a workshop on the island of Rhodes. With ease Apelles brush he combined tireless diligence execution. A number of his paintings, of which, in particular, she was famous for depicting the ancestor of the Rhodian tribe of the hero Jalis, apparently devoted to reproducing the local legends of the island. Yalis was portrayed as a hunter, and his dog, foaming at the mouth and a partridge, was written so plausibly that it delighted even people who are ignorant of art.

Another rival of Apelles, but his enemy and envious, Antiphil, lived in Alexandria at the court of Ptolemy. In addition to large paintings of historical and mythological content, written in tempera, he performed wax paints on pictures of everyday life. His works, such as, for example, "The Boy Fanning the Fire" or "Women Preparing Wool," could apparently serve as proof of the further development of household painting. But he became famous for a new type of painting - caricatures. He portrayed in a ridiculous perspective a certain Grill, with a very transparent hint of his name meaning piglet, and thus gave the name to a whole genus of works (grilles) in the later Greek world.

In relation to the plastic modeling and processing of figures on the plane of the picture, Feon Samoski went the furthest. He depicted on the board a heavily armed warrior in a striker's pose with such relief that it seemed he was ready to break free from the picture. The curtain, jerked at the sound of military music, contributed to the illusion of sight. "Deception itself was the goal, the artist was a market screamer."

Another artist of the end of the 4th century, Aezion, already belongs in part to the era of the Diadochi. Lucian described his picture in detail: "The Marriage of Alexander with Roxana" is a work abounding in the figures of Amurchik, in comparison with which the ancient Roman painting "Aldobrandino Wedding", which is usually recognized as a copy from the original relating to the time in question, is executed in a chaste, simple spirit earlier era. " Description of the painting Aezion made by Lucian, prompted some of the great artists of the Renaissance, even Raphael, to imitate it. The most famous of such imitations is the magnificent picture of the Soddoma at Villa Farnese in Rome. Apparently, from this pore, the little gods of love are beginning to become the usual subject of interpretation in art.

Direction Antifila turned into a special kind of painting in the works Peiriyka. Pliny the Elder said that this artist was loudly famous for his images of insignificant objects and received more praises for his barber shops, shoemakers, donkeys, food and similar subjects, than others for his large paintings. Of course, the artists took revenge on him for this, calling him a riparograph, that is, a mud painter. Be that as it may, Peyrayk attached importance to the special works of painting - not only the images of folk life, but also the pictures of inanimate nature.

Thus, by 300 BC. e. Greek painting took possession of almost all the subjects. The landscape alone remained inaccessible to it. If in some paintings with figures he sometimes appeared in the meaning of the background, he was still very simple and incoherent. To give the landscape an important and independent meaning was destined for the future time of Hellenism. In general, between 450-301. BC e. Greek painting, the very first in the world, crossed the limits that separated planar, flat painting from real painting, transmitting light and shadow, reproducing the depth of space. For several centuries, painters used these acquisitions and then, at the beginning of the Renaissance, they again turned to them.

You can clearly trace the history of the development of external techniques of Greek painting, starting with the unpromising, flat Polygnot painting and ending with the transfer of roundness of objects or at least some semblance of space, opened in Italy, wall paintings, executed more or less handicraft, but imbued with the Greek spirit. , describing the developed art of Apelles and his followers, to trace even further - to the landscape, introduced into the painting of the Hellenistic era. We have already pointed to individual works of this kind, apparently owing their origin to the originals of the glorious pores of Greek painting. The real Greek wall paintings, the very execution of which could be attributed to the 4th century, have survived only in the once Greek Southern Italy.

The Paestum wall paintings depict the return of victorious warriors, foot and horsemen (Fig. 390), the Neapolitan Museum. They are met by residents; women bring supporting drinks to soldiers. The motifs of the depicted movements testify here to a considerably mature art, but placing the figures in one row, in profile, one beside the other against a white background, still does not show those techniques that we should assume in polygnotian paintings. If these works belong to the IV century, it is solely on the basis of historical data. Greek Paestum was conquered in the IV. Lukans, and the clothes in these paintings are Lucas, not Greek, as a result of which it is hardly possible to look at these paintings as works of pure Greek art. In any case, no matter how stylish they are in their own way, the successes that Greek painting made in the 4th century BC are not very noticeable in them.

Fig. 390. Paestum fresco. According to Helbig in "Monumenti dell'Instituto", VIII

In Athens, if we ignore the painting on vases, only one painting is preserved, which can be attributed to this century. This is a picture on the tombstone of the Athens National Museum, described by Late and depicting a farewell scene. It shows the soft contours of groups and the remnants of blue and red inks. But in order to give us an accurate idea of the modeling of the figures, this picture, obviously, is only an exception, replacing the relief used for the gravestone steles, remained too poor.

Regarding Greek painting on vases of the 4th century, which remained true to the flat style, it also cannot be said that it was a reflection of the artistic painting of that time. Its further development affects only in a more free smoothness of contour lines and diversity, courage and dexterity of intersection of figures and groups. In Athens, vase painting, which, as we have already seen, passed through the main stages of its development as early as the 5th century, into the 4th century. gave only a few seemingly elegant, but already devoid of fragrance, belated flowers. The mere fact that neither the potters nor the painters did not consider it necessary to mark the vessels that came out of their hands with their names indicates a little interest in these products. Preference is now given to luxurious robes, figures with wreaths on their heads, poses moving, but beautiful. The protuberances of gold are combined with the protuberances of paints, which are becoming ever more luxurious; sometimes the color relief is combined with red-figure painting. Arrangement of free rows, one above the other, remains the general rule. How much movement the fighting gods and giants have on the same amphora of the Louvre Museum found on the island of Milos! How free and flexible are the forms of the nude body

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)