Architecture

In the vast expanses of Northern Germany, through which the Weser, Elbe and Oder flow with their tributaries, many of the venerable ancient churches continued to be reconstructed in the new style of time. The Church of Our Lady on a meadow in Zesta (see fig. 282) received its northern portal and two towers; the cathedral in Braunschweig acquired the northern side nave, in its twisted pillars, sturdy mesh arches and a flaming openwork binding belonging to the most picturesque creations of the German late Gothic. The cathedral in Magdeburg received a dignified western facade, between the smooth towers of which the middle pediment and the doors unfold all the luxury of late-Gothic decorations. At the end of the century, the Meissen Cathedral was crowned with a tower with three spiers, which then began to enter into custom and is still preserved in the cathedral and the church of Sts. Of the North (Severikirche) in Erfurt system, unfortunately, destroyed by fire in 1547

Of the new buildings in the area of rubble stone, which, descending from the German medium elevation, captures some of the lowland, most of all are Westphalian churches of the hall system, of which the spacious, decorated with leafy capitals should be called. Lambert in Münster, and then also Silesian buildings, such as, for example, the five-church church of Peter and Paul in Gerlitz (1457-1497). Many new churches of the hall system are located in Saxony. The welfare to which the cities of the Ore Mountains were due to the new heyday of their mining industry, prompted them to erect monumental cathedrals or parish churches that met the needs of the new time without reference to the old prescriptions of construction equipment. Since from the very beginning it was assumed that these would be churches for the community or for preaching, their choir was merged into a more integral space with a longitudinal body, they did not make a transept, the side naves were brought to the same height as the middle aisle, and along the walls of the side aisles erected empores that served here to expand space. Of the individual forms of these churches, which include flat mesh arches, there are octagonal columns with concave side planes (like grooves of Doric columns) and curtain arches (see Fig. 406, on the windows), the arc lines of which open upwards. A special type is still the church of St.. Kunigunda (1417–1476) and the Church of the Apostle Peter (ended in 1499) in Rochlitz are almost square buildings resting on four pillars, with a strongly prominent choir that ends with a polygon. A number of churches of the type described in the Ore Mountains begin in 1450 by the Church of St. John the Theologian in Plauen, the plan of which (the modern transept should not be misleading) is adjacent to the square plan of the church in Rohlitz and even seems more consistent than that, as the choir also rises on the square plan. Then follow the Church of the Virgin Mary in Zwickau, whose choir was built in 1453–1475, whereas the longitudinal building with its octagonal pillars with concave sides dates only to the 16th century, and the Freiberg Cathedral (1485–1501), which really standing apart, was only built afterwards. In the cathedrals of Annaberg (1499-1525), Pirna (1502-1546) and Schneeberg (after 1515), the artistic development of the Ore Mountains region reaches its full expression. The restructuring of the castle church in Chemnitz was also carried out only in the 16th century, and this century also includes its remarkable portal, the framing of which instead of beams and bindings consists of trunks and branches (fig. 405).

Fig. 405. Madonna with the saints. The middle portal group of the castle church in Chemnitz. By shteh

In the region of North German brick style, more refined in its stylish correctness than South German, and in terms of its technique, which strengthened the shape of its ornaments with black and colored irrigation, more developed, in the XV century. brisk, active life prevailed. New buildings of the mid-century are, for example, the cathedral and the church of the Virgin Mary in Stendal, the buildings of the hall system with two towers, with nobly made separate forms. The churches of the hall system during this time were built, for example, the five-nave church of the Apostle Peter in Lübeck and the three-nave church of the Virgin Mary in Danzig, with their stalactite-like vaults typical of the late Gothic.

According to the artistic design of its public and residential buildings, North Germany is ahead of South. Already wooden buildings, partition walls are more varied in construction motives and richer in carving. Even in small towns consistently apply the cloisonne system in town halls. The design here is adapted to the needs, but in itself it is of artistic interest. Attractive in their picturesque and richly decorated with dormer windows and turrets, buildings of this kind, in which only the upper floors, one above the other, were built into the partition, represent buildings that have become part of modern villas, such as the town hall in Alsfeld and Fritzlar, Duderstadt and Wernigerode. Halberstadt, Hildesheim and Brunswick are the richest in residential buildings of this style. The gaps between the artfully carved and painted risers and the beams of the skeleton are filled with light masonry of red brick. The windows are always rectangular, only the portals are executed either with a pointed arch, then with a flat one. In Hildesheim, this is the old house of the guild of peddlers (Dreyer's house, 1482), and the luxurious house of butchers (Knochenamthaus), referred by Essenwein to the XV century, appeared only in the XVI century. For the upper, protruding floors it is characteristic that the roof above them protrudes into the street more than 2 meters from the bottom of the house. In Hildesheim, the partition walls are turned to the street by gables, while in Brunswick, where most of these buildings of the 15th century are preserved, they usually turn their roof gutters onto the street. A distinctive feature of the carved beams of Brunswick houses, according to Lakhner, is the so-called stepped frieze, which, for example, on one house of the St. Aegis 1461 was decorated with small children's heads, and often also other images.

Among the brick town halls of Germany are famous for their finely decorated gables of the town hall in Tangermünde and Konigsberg in Neymark. In a mixed style of facing bricks with decorations, the picturesque town hall in Breslavl is sustained, luxuriously decorated with lush cross-cuttings, phials, dormers and towers. The residential houses of the “brick” style of this era, which, as a general rule, have stepped gables adorned with blind or flat arches, are facing the street, especially the Baltic cities are so rich that it is not possible to mark them separately. We should not forget, however, some city gates with towers belonging to the most brilliant works. In Lübeck, this includes the Castle Gate and the Holsteen Gate, which were completed in 1477. The brand possesses in such cities as Stendal, Neubrandenburg, Konigsberg, Stargard and Pirits, a whole panorama of picturesque and beautiful residential buildings and military structures of this kind.

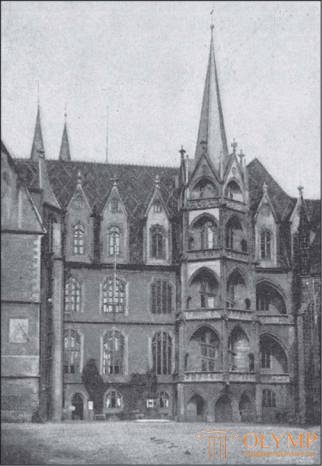

Fig. 406. The courtyard side of Albrechtsburg in Meissen. From the photo

In the region of Northern Germany, which has a rubble stone, Goslar possesses the most beautiful town hall in the late Gothic style of the 15th century. The German civil architecture of this era reaches its apex in a huge stone structure, high above the Elbe - Albrechtsburg in Meissen (Fig. 406), built between 1471 and 1481. architect Arnold of Westphalia, is the joint residence of two brothers, sovereigns - Ernst and Albrecht of Saxony. From the side of the steep bank of the Elbe, it fits to the uneven ground, like a castle, and from the open, flat side, like a palace, this impressive building is generally more a palace than a castle. All rooms are covered with arches with pointed arches, some are supported by pillars, some are equipped with rich mesh arches, others are stalactite. Large windows located in deep niches end partly with the curtain arches already described, which, apparently, for the first time passed from here into Saxon church building. All the strengths and weaknesses of the German late Gothic are manifested here with the greatest clarity.

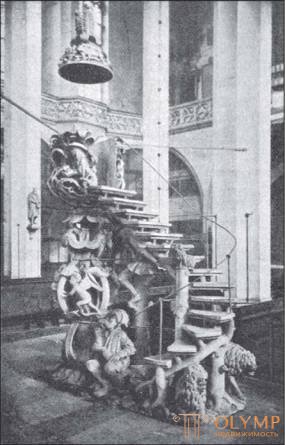

Fig. 407. The Cathedral of the Cathedral in Freiberg. By shteh

Sculpture

Throughout the vast region of Northern Germany, artistic carving was more prevalent than stone sculpture and bronze casting, which was still limited to few, more artisanal than art foundries. During the first half of the 15th century, the sculptural workshops of various North German cities, without deviating from their previous path, strove for freedom. During the second half of the century, South Germany, especially Franconia, began to manifest itself in the south and east of this entire region, while to the west and north of Westphalia, which had long maintained relations with the Rhineland region specified by Nordhoff, the Rhenish or even Zarean influences.

The center of northern German stone sculpture of this era was North Saxony. In the Holy Sepulcher, made around 1475, for the Church of Sts. Bartholomew in Dresden (now the local museum of antiquities), we see the responses of the Kraft school, in parallel to which it goes. The faculty in the Cathedral in Freiberg (Fig. 407), which arose, we must think, around 1500, denotes the flourishing of the already mentioned fantastic-realistic Saxon tree style, although not invented in Saxony, but used here, like later, around 1500 g ., a special location. The ancient stone pulpit has the shape of a fantastic flower with a tulip-shaped calyx, the stem and leaves of which are fastened with stone ropes to a tree trunk carved from stone too. The figures of the saints, the realistic figures of the peasants (the artist is depicted in the form of a shepherd with his dog) and the little winged angels are wittyly arranged and enliven this remarkable structure, which is stylistically impossible, but not artistic in terms of art. It stands for unlimited artistic arrogance between the time of the Gothic and the time of the Renaissance.

The development of North German stone sculpture of the XV century. appears before us in Erfurt, Magdeburg and Halberstadt. In Erfurt, small, lively reliefs of donors (1422-1429) in the cathedral and church of preachers testify to the first breath of the new time. The alabaster high relief of the Archangel Michael (1467) in Severikirche was completely made in the style of the XV century, and the relief in 1494 with the image of the Madonna in the church of St. Bartholomew shows more brute force than the artistic charm of a realistic style. In the Magdeburg Cathedral stone statue of Archbishop Albert IV of the first half of the century is full of naturalness and life, but the statue of Madonna on the main pillar near the pulpit has troubled folds of clothes, although this statue has the famous grace of the last quarter of a century, and the tombstone of Empress Edete borrowed branches of Saxon arboreal style of the end of the century. Finally, if in the cathedral in Halberstadt the apostles (1422) in the choir represent poor handicraft work, then in one of the choir chapels there is a somewhat later beautiful statue of Our Lady standing, and then in the other chapel - a great relief with “Adoration of the Infant” (1517), showing a further change in the late Gothic style during the transition to the Renaissance style.

Apostles on the pillars of the church of sv. John the Theologian in Osnabruck, in northwestern Lower Saxony, represents the transition from the Gothic bombast of the second quarter of a century to the strong realism of the last quarter of this era, while the stone relief on one of the towers of the cathedral in Münster is performed in the spirit of the new time.

The rich artistic life was different in the XV century. Lubeck is the main city of the Hansa. It was here, as Goldschmidt showed, that after 1400 stone plastic, using Westphalian sandstone, came to the fore. The first third of this era includes several statues of apostles and wise and foolish virgins, still gothic curved, now preserved in the choir of the church of Sts. Catherine. By the middle of the century, Goldschmidt attributes the Madonna as a mature woman with a naked Infant Christ on her arm, standing outside, on the western portal of the Church of Our Lady. Actually, by the end of the century, four large bas-reliefs follow the eastern railing of the choir of the Church of Our Lady, generally calmly and calmly representing the Washing of the Feet, the Last Supper, the Prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane and the Taking of Christ into custody, with separate features taken from life.

The only Northern German bronze wares of this time also belong to the churches of Lübeck: in the cathedral there is a brass font (1455) with angels supporting it, and beneath the keel-shaped arcades of its core are Christ and the apostles; in the church of the Virgin Mary, a brass tabernacle (1476–1479), compared with the high German tabernacles, is less skilful in its forms.

Hundreds of late-Gothic carved altars have been preserved. Some still stand in their former places, but most of them went to the provincial archaeological museums of big cities, like Berlin, Breslavl, Dresden, Münster, etc. Most of the Upper Saxon carved altars belong to the middle of the 16th century, while in Thuringia, where Saalfeld and Erfurt possessed significant woodcarving schools, and very important works of this kind were preserved from the 15th century. Famous Westphalian altars, such as the altars in Haltern, Freden, Dortmund (Church of the Apostle Peter), Bielefeld (St. Nicholas Church), etc., which until recently were considered first-class local works, turned out to be Antwerp works, and others, like Altars in Osnabrück (Church of the Apostle John the Divine) and Dorsten, - Brussels works of the first decades of the XVI century. Silesian carvings differ from Brandenburg, and Hannover from Pomeranian only some provincial features that are easier to see than to identify in words. The German manner of making figures in medium kivots large in some localities is struggling with the Dutch tradition of making these figures small.

Quite German, and, moreover, North German, is, for example, the altar kivot of the Lübeck Guild of Sts. Luke (1484), in the local museum. The middle part of it depicts the evangelist Luke, writing Madonna. However, among the surviving Northern German carved wooden works, only a few rise to the real art. It should be called, for example, the sedentary image of St. Dominic in the Minorite Church in Leipzig, which we, along with Shmarsov, consider no more ancient than 1400, 12 still Gothic Lubeck apostles of the first half of the 15th century, at the National Museum in Munich, and touching, extremely carefully made in all details “Crying over the body Christ ”(circa 1500) in the Church of the Virgin Mary in Zwickau. The question of whether the Upper Saxon masters of Frankish origin, remains open.

Painting

To what extent art in the XV century. It has already become the common property of Germany, show numerous remains of frescoes and even more numerous easel paintings of this time, also preserved in Northern Germany. Apart from the works of the band that stretches from Westphalia through Hanover and Hamburg to Lübeck and conquers the Scandinavian and Baltic north, painting here is at a lower artistic level than in the more distant parts of the west and south of Germany. Frankish influence dominates in Upper Saxony, Thuringia and Silesia. In Brandenburg, the 15th century frescoes of which were described by Georg Voss and the altars by Münzenberger, a certain independence of the artistic invention prevails in the field of painting, however, not leading to such incomparable works as in architecture. In the already mentioned northwest strip since the last quarter of the century, Dutch painting had a more direct influence than in other areas of Germany, but much here, which could have seemed like imitation at first glance, should be attributed to common origin .

Of the northern German murals on the walls and ceilings of this epoch, we note here only the frescoes in the town hall in Goslar, formerly attributed to Michel Volgemut, but they are undoubtedly of South German origin. On the ceiling are depicted four events in the life of the Savior, surrounded by twelve prophets and four evangelists, and on the walls are twelve Roman emperors, alternating with twelve Sibyls. In its symbolic composition, this series of paintings, the free forms and the confident writing of which extend beyond the 15th century, stands apart between the preserved German monumental works of the time.

Мы не будем рассматривать северонемецкие витражи, из которых пользуются известностью окно хора 1467 г. с изображением Страшного Суда в приходской церкви в Вербене и окно хора прежней замковой церкви Девы Марии; также не будем останавливаться на книжных миниатюрах этого времени. Но все же напомним, что среди иллюстрированных книг некоторые любекские печатные произведения занимают выдающееся положение. Среди светских исторических книг отметим напечатанную в 1475 г. «Хронику» Луки Брандиса, а среди священных книг — Библию 1494 г., которую вместе с появившимися в 1489 г. гравюрами на дереве «Пляски мертвецов», в Германском музее Нюрнберга, Гольдшмидт связывал с любекским живописцем Нотке (см ниже).

Гравюра на меди в продолжение этого времени процветала только в Вестфалии. В Бохольте работал Израэль ван Мекенем, сын переселившегося сюда мастера берлинских «Страстей Господних». Хотя Израэль копировал многие гравюры южнонемецких мастеров, но его интересные гравюры с поясными автопортретами и портретами его жены показывают, что его нельзя сбрасывать со счетов.

Главную роль в Северной Германии играла станковая живопись. Повсюду встречаются имена художников, открытые в архивах Альвином Шульцем для Бреславля, Гейзером и Вустманном — для Лейпцига, Гольдшмидтом — для Любека; точно так же нет недостатка в алтарях с картинами на створках, но большинство их стоит на такой ступени искусства, которая показывает, что большинство указанных живописцев были только ремесленниками. Все же в качестве более утонченной саксонской работы начала XV в., весьма вероятно ведущей начало от пражской школы, мы отметим картину на доске в церкви миноритов в Лейпциге, указанную Шмарсовым. На одной стороне Дева Мария сидит перед пишущим св. Домиником, открывая ему религиозные тайны; на другой изображено на золотом фоне Благовещение. Наоборот, нюрнбергское влияние видят в «бреславльском мастере 1447 г.», алтарь которого со св. Варварой, в Музее древностей главного города Силезии, напоминает алтарь Тухера в Нюрнберге; однако возможно, что и он непосредственно примыкает к пражской школе. Более удачным представляется вертенбергский алтарь 1468 г. в соборе в Бреславле, в котором Тоде видел более зрелое произведение мастера св. Варвары. Совершенно изменившийся стиль последней четверти века предстает в четырех замечательных алтарных створках церкви августинцев (Reglerkirche) в Эрфурте с изображением на оборотных сторонах больших фигур святых, а на передних — новозаветных событий, в чрезвычайно неловких, даже искривленных формах, но представляющих талантливое применение красок, проникнутых светом. Что художник, которому Тоде приписывал даже «Венчание терновым венцом» и «Перенесение креста» вольгемутовского алтаря в Цвиккау, выучился своему искусству в Нюрнберге, на самом деле весьма вероятно.

Мы уже знаем, что станковая живопись в Вестфалии, по крайней мере, была такая же древняя, как в Нюрнберге, если не древнее. Но из этого не вполне ясно, почему развитие древней живописной манеры XIV в. в новый живописный стиль XV в. совершилось здесь в зависимости от кёльнской живописи. Вестфальцы XV столетия принадлежали к имевшим наибольшее значение германским ветвям, их живопись, средоточием которой оставался по-прежнему Зёст, развивалась самостоятельно в соответствии с духом времени. В лице Конрада из Зёста, с которым нас ознакомил Нордгофф, мы встречаемся уже в самом начале XIV в. с сильным, хотя и не гениальным мастером. Исходную точку для суждения о нем дает помеченный 1403 г. подписанный его именем большой алтарь в церкви в Нидер Вильдунгене, из трех частей, с Распятием в средней части. В пределах традиционных главных формул, к которым, само собой понятно, относится золотой фон, здесь пробивается могучий порыв к природе и жизни. «У подножия креста, — говорил Альденгофен, — сходятся рослые фигуры вестфальского дворянства и приземистые крестьяне. Есть и собаки. В святых женщинах много тонкого и правдивого выражения. В картинах левой створки от Матери и Младенца веет сиянием прелести». Руку того же мастера мы видим, например, в картине с золотым фоном в церковном доме св. Патрокла в Зёсте, представляющей св. Николая с основателями — духовными лицами, и в створках со св. Доротеей и св. Одилией в музее в Мюнстере. Зрелый вестфальский стиль второй половины столетия мы видим впервые в «лисборнском мастере», то есть в художнике, написавшем картину главного алтаря монастырской церкви в Лисборне. Алтарь с картиной «Распятие» все еще на золотом фоне был освящен в 1465 г. К сожалению, от него сохранились только разрозненные фрагменты: восемь частей, в Национальной галерее в Лондоне, и вырезанный кусок с благородной головой Спасителя и ангелы, в музее Мюнстера. Определенный, ясный рисунок, прекрасная моделировка и светлые краски отличают это мастерское произведение немецкого искусства, в котором реальность и чувство красоты явились в редком для того времени сочетании.

В главных сохранившихся произведениях Ганновера известная самостоятельность сочетается с вестфальскими отголосками. Отметим грубо выполненный большой алтарь с двумя парами створок (1424) брата Германна из Дудерштадта, в музее Ганновера. В Распятии его средней картины сугубо реалистические детали — у одного из разбойников на кресте течет кровь из носа — соединяются еще со старой неумелостью, пластической и живописной.

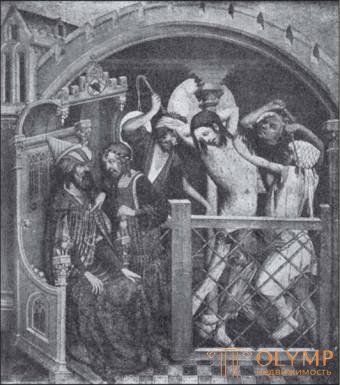

Fig. 408. Бичевание Христа. Картина мастера Франке на алтаре св. Фомы в галерее искусств в Гамбурге. С фотографии Нёринга

Гамбург был центром северонемецкого искусства XV в. Мастер Франке, начавший писать в 1424 г. алтарь св. Фомы для общества купцов, поддерживавших сношения с Англией, своей самостоятельной силой в пределах переходного стиля от идеализма к реализму, стильностью и в то же время естественностью, блестящими, гармонирующими красками и убедительностью страстной манеры рассказывать превосходит всех своих немецких современников. Важнейшее его произведение, в Гамбургской галерее (Kunsthalle), заключает: в средней картине, на золотом фоне, — «Распятие», от которого, к сожалению, сохранился только фрагмент; на сохранившихся внутренних створках, с внутренней стороны, точно так же на золотом фоне, — «Бичевание» (рис. 408), «Распятие», «Положение во гроб» и «Воскресение», а с наружной стороны и на внутренних сторонах наружных створок на красном фоне, усеянном золотыми звездами, в верхнем ряду — четыре события из жизни Девы Марии, а в нижнем — четыре сцены из жизни и кончины св. Фомы Кентерберийского, которому был посвящен алтарь. Как захватывающе действует «Бичевание», как тягостно — «Несение креста», какое мощное «Воскресение», как стильно, правдиво и величаво изображено «Поклонение волхвов» и как сумел мастер перевести историю английского святого на ряд убедительных картин, не имея предшествующих образцов! Несомненно, работой мастера Франке являются и трогательные изображения Христа в терновом венце, в Лейпцигском музее и Гамбургской галерее, из которых первое, должно быть, произведение более раннее, чем алтарь св. Фомы, а последнее — более позднее. Гораздо сильнее всех вестфальских наслоений и всех откликов упомянутой уже картины того же времени в Ганновере — самостоятельное, полное художественной силы творчество этого мастера, о которое разбиваются все односторонние теории различных влияний.

В это время любекская школа перерабатывала воспринятые ею вестфальские и нидерландские влияния. Обратимся к ее двум мастерам.

Один из них назвал сам себя на своем произведении Германом Роде; другой в многочисленных документах 1467–1501 гг. называется Бернтом Нотке. Главное произведение Роде с его подписью — алтарь св. Луки (1484), в Любекском музее. С его резным алтарем мы уже ознакомились (выше). Когда он закрыт, то на фоне далекого пейзажа под голубым небом с нежными переходами тонов видны все еще слегка изогнутые стройные, бледные фигуры св. Екатерины и св. Варвары; если раскрыть створки, то перед нами будут в двух рядах одна над другой восемь картин из жизни св. Luke. С первого взгляда эти изображения напоминают, конечно, нидерландские картины, но слабее их по рисунку и мягче по тонкому, очень плавному письму. По выражению Гольдшмидта, они кажутся «точно покрытыми нежным пушком». Из остальных произведений, которые на основании этих картин следует приписать Роде, мы назовем алтарь 1468 г., в Историческом музее в Стокгольме, алтарь 1482 г. в церкви св. Николая в Ревеле и два украшенных библейскими картинами диптиха 1494 и 1501 гг. в церкви Девы Марии в Любеке.

Notke, known by the sources Lubeck master, adhered to a completely different direction. It is closer to the Upper or Middle Rhine masters; it is firmer in contours, more plastic in modeling, more natural in the image of nature, and more convincing in composition than Rode. His documented works are the main altars in the Cathedral in Aarhus (1479–1482) and in the Church of the Holy Spirit in Revel (1483). In Lübeck, the altar of God's Body in 1496, now in the museum, belongs, apparently, at least to his workshop.

Thus, we saw how German painting, through the intermediary of the city of Hansa, spreads to the most remote shores of the Baltic Sea.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)