The long period of the history of Chinese culture and art, following just considered, bears the imprint of Buddhism. Back in the 1st c. The "doctrine of self-redemption" was brought to China from the banks of the Ganges, but only after the second Han dynasty died out, did this doctrine spread to the Middle Empire to such an extent that it mastered the spiritual life of the educated classes. Wee Guy, the first of the Chinese artists who painted Buddha images, worked around 300 AD e. When the emperor Giao-u-ti in 381, he built a temple in honor of Fo in Nanjing, as the Buddha in China was called, the whole country worshiped this saint. In the VI-VIII. Foism remained the dominant doctrine in China, but in the reign of the Tang dynasty, around the middle of the 9th century, the adherents of the ancient Chinese religions erected persecution of this doctrine. Up to 45,000 Buddhist temples and monasteries were destroyed, and only 400 years later, the Indian teaching, which was never completely eradicated in China, once again triumphantly raised its head in it.

Perhaps, no new teaching has ever been reflected in the art of any country as fruitfully as Buddhism in Chinese art. Most of the numerous Indian original works - statues of the Buddha of various sizes, Buddhist paintings and utensils, imported into China in the first centuries AD. e., - died in the turbulent time of the IX century, but they served as models for Buddhist-Chinese works and completely transformed all Chinese art. Under the guidance of their Indian teachers, the Chinese began to look closely at nature more and more attentively, with more thoughtfulness; The former Hellenistic influences, connecting now with the Indian ones, represented to the Chinese both people and animals, and the plant world in more artistic forms. But now Chinese artists already knew how to subordinate all foreign elements to their innate taste and give their utensils to clay, jade and bronze vessels a special Chinese imprint, telling them at the same time more harmonious proportions and more luxurious forms.

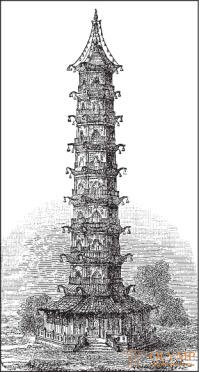

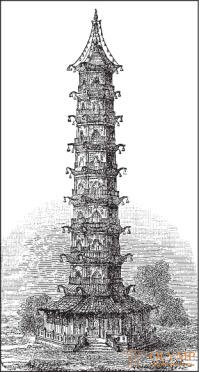

The architecture, without losing its Chinese character, was enriched with pagoda towers with 9-13 tiers that have Buddhist origin in all of China. They originate from the upper parts of the Indian stupas, which is especially clearly proved by the transitional forms in Nepal. The Nanking Tower, later known as the Porcelain Tower, the same as the thousands built in China in its original form (fig. 588) belonged already in the 4th c. n e.

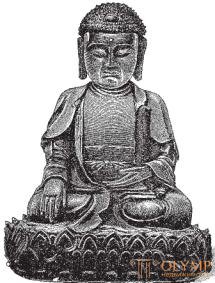

A large Chinese sculpture has developed into completely round, although designed only to look at them from the front, figures of gods and saints, made of stone or of gilded bronze. Chinese statues belonging to the 8th century, gigantic figures, excised from natural rocks in Gang-chow and Shin-chang (in Che-kiang province), one of which is 12 meters high and others above 20 meters, depict Buddhist saints. To understand the position of the numerous bronze Chinese statues of Buddha in the history of the development of the art of all mankind, the connection established by Grunwedel between the forms and types of Buddhist-Chinese art and the art of the Gandhara school on the north-western border of India is important.

Fig. 588. Porcelain Tower in Nanjing (now destroyed). According to Ferguson

Since, in general, in religious terms, China adopted the Northern Buddhist teachings of India, partly with an admixture of Brahman elements, it is easy to explain to yourself the fact that in artistic terms, China borrowed the language of forms from the Gandhara school, which developed it under the influence of the world of Greece or even Rome. As there is no doubt that the main type of Buddha images in the Gandhara school should be recognized as Indian, and not Greek-Roman in origin, it is so certain that all the numberless Chinese figures of the Buddha, who is sitting with his legs tucked under a lotus bowl frontal position - Indian, not Greek; but all that in the Gandhara school can be considered an echo of Greco-Roman art, the freer arrangement of the folds of clothing, sometimes the method of treating hair, greater certainty of the transfer of the forms of the human body, the movements — all this is repeated in Chinese sculptures and even more in pictorial images, so, despite all the Chinese alterations and additions, they contain a lot of clear indications of their Greco-Roman origin. The Buddha, sometimes presented in a standing position, is a true ideal type of Chinese art. The main female ideal type of this art, Guanyin, the goddess of mercy, portrayed with a baby in her arms or in her bosom, sometimes reminds of the Christian Madonna, for which she was accepted. Thanks to the almost Aryan forms of these figures and the expression of peace of mind on their faces, they occupy a special position in Chinese art. The bronze Chinese statue of the Buddha (fig. 589) is in the Chernuski Museum in Paris; The porcelain figurine of Guanyin (see fig. 599), belonging to a later time, is stored in the Dresden collection of porcelain products.

In the period under consideration, Buddhist painting was predominantly done by bonzes in their monasteries. They portrayed legends about the Buddha, neatly and deeply felt, on long scrolls of silk matter. Along with them, secular officials from the VII century. tried their hand at portraiture, in the depiction of animals and in the landscape. The most famous of the subsequent Chinese painters were for the most part also officials, writers, or musicians.

Fig. 589. Buddha. Bronze statue. According to Paleolog

Thus, under the influence of Buddhism, the Chinese civilization in the first centuries of the Tang dynasty (618-907) reached a peculiar heyday. In the public life of China, the desire for the spiritual beautiful reigned. In small art still prevailed still products made of bronze and jade. Jade cups, drawers, tubes, handles for brushes and flower bouquets were extremely soft and elegant forms. On solid stone, as well as on bronze, lotus flowers, fig tree leaves, fish pairs, single-leaf shells and all other sacred symbols of Buddhism were depicted in the form of ornaments. To the ancient Chinese fantastic animals were added the sacred animals of Buddhism, especially elephants and lions. Lev Fo, in his painted look, sometimes more like a dog than a lion, has played a major role in Chinese bronze, stone, and soon earthenware, being as temple guard, altar guard, or figure, decorating household utensils. The original Indian sacred hooked cross, the swastika, in Chinese one wang (van), penetrates Chinese art together with Buddhist flower stars and often serves as the main element of extremely intricate hooked patterns.

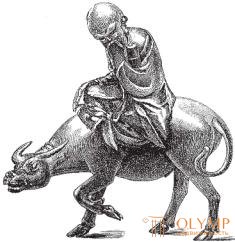

Fig. 590. Lao Tzu. Bronze group. According to Paleolog

In general, Buddhist art was a representative of idealism in China and at the same time foreign classicism. Therefore, it is natural that the Taoist reaction, which was found in the entire spiritual life of China from the middle of the 9th century, in Chinese art made a return to forms more national and realistic. The main Taoist saint remained Lao Tzu, who, in complete contrast to Buddha, was depicted as a bearded, bald man with a strongly developed skull, riding a bull or a deer. Fig. 590 represents one of the figures of this saint in the bronze group of the Chernuski Museum in Paris. This figure was often mistaken for the image of the god of longevity, which one can actually recognize it in view of the fact that if there was no real mythology, which would have arisen from popular beliefs, in China there was a general need to deify and personify abstract concepts. Prominent people, centuries later after their death, were also ranked as gods; Kuan-ti, the great commander of the Han dynasty, became the god of war; The often-mentioned eight Chinese sages, Pa-siens, became the main characters of the Chinese Olympus, which, however, were portrayed only at a later time, distinguishing each with special attributes. Then, among the Taoist symbols that came into use in Chinese artistic language are: a peach tree, fruits, flowers or branches of which are constantly found in ornamentation, marking the duration of earthly life, a circle divided into dark and light parts with a curved line in the shape of the letter S , meaning gender difference, and, according to some, also a bat, which others view as a Buddhist symbol, as its name resembles Fo's name. In short, when by the end of the Tang dynasty, around the middle of the 9th century, Buddhism temporarily ceased to dominate in the spiritual life and art of China, in this country there had long been no shortage of national images, symbols, and ornaments that were only expected to be used in art.

Paintings of the Tang Dynasty (681-907) are known to us almost exclusively from Chinese literary sources and from the drawings accompanying them. The well-known Buddhist painter in this era, E-syong, a native of the border with India, used a special, alien to China method of writing, which is of great importance in the history of art because Korean painting originated from E-syong, and the ancient Japanese painting adjoins this one.

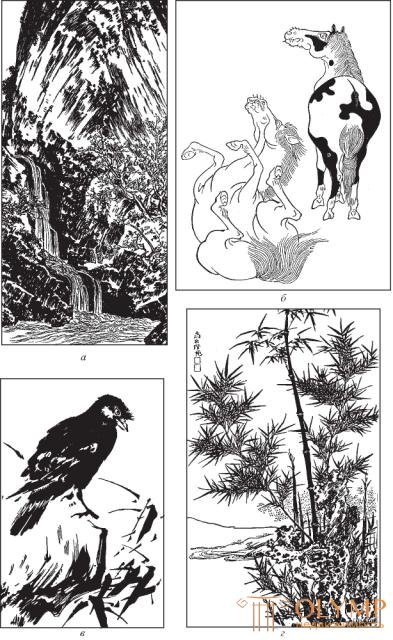

National Chinese painting in the VII and VIII centuries. divided into northern and southern schools. In both schools, the landscape was cultivated, and in them for the first time in the entire existence of the world, landscape painting began to clearly reflect human sentiments in itself. The landscape painter of the northern school, Li Si-syun, who lived in 651–716, was a representative of coloring, namely, a golden-green tone. The landscape school of the southern school, who lived half a century later, the famous Van Wei (O in Japanese), invented two-tone painting, worked in black ink on a white background. All the famous later artists who worked in the same way, recognized themselves as followers of Wang Wei. In the Munich collection Fr. Geert is the image of a banana in the snow, which is considered to be an unquestionable copy of the original Wang Wei. The mood produced by this landscape is achieved by comparing opposites, as in the famous poem Heine about pine and palm (“In the north is wild ...” and so forth). One of the first followers of Wan Wei, Wu-tao-tzu, in Japanese Godoshi (about 720), is mentioned almost more often than he. Wu-tao-tzu became famous for his mountain landscapes (Fig. 591, a) with images of Buddhist legends and scenes taking place in temples. His painting "Nirvana Buddha", preserved in a temple in Kyoto in Japan, recalls the Gandhara reliefs, the style of which continued to be reflected in the compositions of this school. The cultivator of Chinese animal painting is considered to be Gan Kan (about 750), who owns a drawing of two horses (b).

Fig. 591. Chinese painting: a - Woo-tzu. Landscape with a waterfall; b - Gan Kahn. Sketch with horses; c - Yu-k'ien-Tsien-tun Vorona; Mr. Mu Ki. Bamboo. According to Anderson

The period of the full bloom of Chinese national painting is the era of the great Song dynasty (960-1278). The lower the Buddhist painting in this era fell, the more magnificently the landscape and the painting of flowers and animals flourished. Paints at this time is attached less value than the picture. The pride of the artists of the Song Dynasty is a wide technique of drawing with ink on a white background, quite a picturesque of its kind. The contours in it are often quite concealed. With such a simple technique, pictures of nature are reproduced with amazing magnificence and truth. Li Cheng, the head of the northern school (about 1000), was valued as a landscape painter, endowed with such fine observation, that his background went "seven miles" away. Kuo Ki (Kivakki in Japanese) is spoken of as a master of portraying melancholic winter species. Tun Yuan (circa 1000 AD) attributed one landscape to the Geert collection, which depicts a white mist swirling at the foot of the gigantic mountains, and in the foreground is a valley with a river thickly overgrown with trees. "White Falcon", in the same collection, is considered a copy from the picture of the emperor Gui-Tsung himself, whose reign (1101-1126) Fr. Geert called the "medical (healing) era of painting and the heyday of museology" in China. This picture, executed strongly and simply in the colorful respect, is imbued with external calmness and inner life.

At the end of the Song Dynasty, the predominance of purely Chinese artistic techniques began, and the painters began to take individual objects from nature available to the closest observation and transform "foreground sketches" into independent works of art. Apparently, in China, along with the cessation of travel to the mountains, which became more difficult at that time, but still continued with the purpose of pilgrimage to solitary Buddhist monasteries, artists lost the desire to depict large, complex landscapes. The educated Chinese began to see nature almost only in his garden. Thus, there was a subtle observation and subtle transmission of individual trees, branches, flowering bushes of peonies, carnations and chrysanthemums, birds and butterflies - what could be seen without leaving the garden. If we call the brothers Ma Yuan and Ma U, who wrote in 1180 ate, cypresses, cedars and rocks, Su Che, Uyen-t'ong and Yu-k'ien-Tsien-tuna (v), whose specialty was the image of bamboo as a work of art, Goei-tsonga, a painter of wild geese, Mao Yi (circa 1170), a painter of domestic ducks and pigeons, and Mu Ki, a very versatile animal painter (d), then we only mention a few prominent artists from among eight hundred, whose names are found in yearbooks of the Song Dynasty. Of their works, as Girt wrote, very few survived; but all experts recognize that under this dynasty the Chinese surpassed all the peoples of Europe, at least in painting.

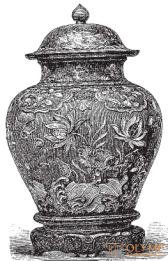

Fig. 592. Porcelain vase of the Song or Yuan dynasty. By du sartel

Hippisli and Geert agree with Hradidier and Bushel, experts and writers on Chinese porcelain, that the most ancient extant china articles from China belong to the Song dynasty. Chinese writers tell, of course, fairy tales about ancient porcelain, but it is impossible to determine with certainty how much they are talking about real porcelain, solid, sonorous and transparent material. The Song Dynasty porcelain is glazed almost exclusively in the same color and painted with only a few refractory colors. Ornaments on it, sometimes simply deepened in the form of grooves, sometimes consisting of leafy motifs or of symbolic images of animals, slightly protrude under the glaze or extruded using patterns. The main forms of these ornaments are borrowed from plastics on more ancient bronze vessels; but sometimes they are taken from nature, copied from some animal, flower, fruit, ancient bowl made from a human skull. In fig. 592 - porcelain vase with a similar kind of ornament, belonging to the Song dynasty or (more likely) Yuan and located in the collection of L. Fulda in Paris. Already at that time, porcelain covered with fine, hair-like cracks (cracked) also played an important role. Wrong mesh pattern, formed by chance during the cracking of the glaze, began to be considered a kind of charm, raised to the level of artistic motive and began to deliberately seek to obtain a network of these tiny cracks. He was also famous for Tin Yao headlights , usually white, but sometimes also purple-red or black. But the best preserved is greyish, bluish or olive green solid porcelain (Yao) from Luntz Yuan, known as celadon. In terms of its shape and color, it is an imitation of jade, which was in great honor, and which it is trying to replace, is an interesting example of how artistic features are further developed thanks to tradition. This porcelain owes its hardness to the fact that it has been preserved both in China and in Japan, both in the East Indian archipelago, and on the shores of the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf; its locations, as proved by Geert and A. B. Meier, mark the paths along which Chinese trade of that era went.

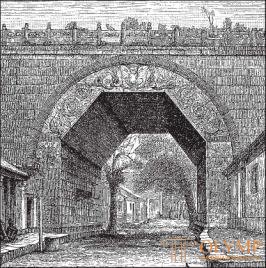

Fig. 593. Gate with a vault in the Nankau Passage. According to Ferguson

Khubilai-kaan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, a Mongol-Tatar conqueror, in 1260 forcibly put an end to the Song dynasty; there was also a violent coup in the whole spiritual life of China, coupled with the change of the dynasty reigning in it. Khubilai was a visionary sovereign. При его дворе в Пекине собирались послы, ученые и художники со всего света. Религиозная замкнутость сменилась широкой веротерпимостью. В Китае стал распространяться ислам, но сами завоеватели исповедовали зародившуюся в Тибете ветвь буддизма, которая, под именем ламаизма, заняла место рядом с фоизмом. Духовный глава этой секты, далай-лама, имел в то время, как и теперь, свою резиденцию в Лассе, главном городе Тибета; но пекинский великий лама вскоре приобрел в Китае господствующее влияние. Ламаизм внес с собой целые полчища полубогов и святых, как свидетельствуют о том изображения самых важных и популярных из их числа, изданные в количестве трехсот Пандером под заглавием "Пантеон Чангча-Гутукту". Со своей стороны, фоизм и даосизм начали теперь, из-за соревнования с ламаизмом, увеличивать сонмы своих святых. Вследствие всех этих взаимодействий образовалась богатая китайская иконография, исследованием которой наука только еще начинает заниматься.

From the time of the Yuan dynasty - this is the name of this dynasty of the Mongolian conquerors, which reigned in China from 1260 to 1368 - some buildings, namely city walls and gates, have survived; of these, the Beijing gates, built in 1274 and converted in 1409, are particularly remarkable in their arches. The gates with an arch in the Nankau Passage beyond the Great Wall are also curious (fig. 593). On the one hand, the true set of these gates represents an angular section entirely in Chinese taste, on the other - their embossed decorations have a purely Indian character: curls of vegetative ornament pass right and left into a figure of a serpentine man (Naga), and on the castle stone between these figures Garuda with outstretched wings.

Indian and Persian influence is also reflected in the slender, long-necked forms, and sometimes in the ornamentation of bronze and porcelain vessels of the era under consideration. From the west, cellular enamel technique penetrated here, in which separate spaces filled with colored alloy are separated from each other by metal wire. This technique has been used primarily in the ornamentation of bronze products, and it can be said that then no people in the world could match the Chinese in the art of its production. Cobalt blue paint, brought by the Arabs to China as early as the 10th century, came into use at the same time with the single-color glazing of porcelain vessels. Now the imperial porcelain factory in King-te-order, founded back in 1005, has come to the fore. But Grandidier and Buchel generally attributed the porcelain of this period to the era that preceded the full flowering of Chinese art.

As for Chinese painting, they find that foreign influence was barely noticeable during the Yuan dynasty. But in painting from life, both in small and large size, the place of bold, wide reception of execution and simple colors of the classical school of the Song Dynasty was occupied by lace work and diversity of color. The result of the revival of Buddhism in China, of course, was the revival of religious painting, the development of which was equally promoted by Foism and Lamaism, as a result of which a wider career opened up for it. Its main representative at this time is considered Yen Guo, sometimes flourishing activities of which were the last decades of the XIII century.

Among the most famous painters of the national trend who survived the change of the Song dynasty was the Yuan dynasty, Geert reckoned Chau Myung-fu, the court master, who died in 1322. There are many copies and imitations of his full-life horse images. Geert owned a genuine painting "The Rooster, Locust and Flowers" by Chien Shun-chyu (1264), a contemporary of Chau Myung-fu, who worked a little later. In the British Museum there is a picture of another talented master, an animal painter who worked during the Yuan dynasty, Chau Tau-lin, - "The Tigress with her cubs". Of the landscape painters of that era, four masters are known, adjacent to the direction of Van Wei. One of them, Lee Chuan, owns the painting "Dead trees", which was in the Geert collection. The love for such "sad" subjects developed along with the taste for their simplest reproduction. It may be surprising to some simple means that Chinese artists depicted nature on a plane, without fear of reproach that the unfinished is given by them for the finished.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)