Starting to talk about the prehistoric art of the north of Europe, we must, from a review of the high, free and mature creations of art, return once more to the consideration of works that are much less perfect and primitive. The classic site of the first Iron Age north of the Alps is the Hallstatt cemetery in South-Western Austria, excavated in the 1850s. and described by Fr. Von Saken. To designate the whole culture of the first iron epoch of Central Europe, the term “Hallstatt era”, or rather “Hallstatt culture”, came into use. The later, in comparison with it, the Bronze Age of the North for the most part continued in parallel with the more ancient Hallstatt culture. The iron, which brought with it the language of the forms of the previously matured south, has already spread in the eastern Alpine countries at that time, as the northern Europe itself could still do without this metal. Whereas in the ancient Hallstatt era (700–500 BC) the southern influence apparently came more from the Balkan than from the Apennine peninsula, the later Hallstatt culture (500–300 BC.) was dependent on her modern and more ancient Italian art. Görnes called this influence of Italian art on the more youthful Hallstatt culture "the first world action of Italian art." There are two belts of Hallstatt culture - the southern and the northern. The southern belt, in which its carriers are considered to be Illyrian tribes, akin to the Wends of Upper Italy, covers a space from the Adriatic Sea to Central Styria; the northern one, in which the culture was supposedly spread by Celtic tribes, stretches to the Danube, embraces Bohemia and Silesia, goes up the Danube to the west, beyond the sources of this river and even beyond the Rhine.

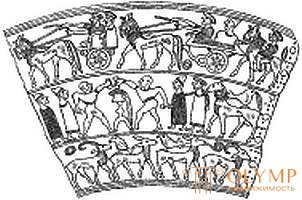

Fig. 540. Situla from Vatsha (in expanded form). By ranke

In respect of some art products found during the Hallstatt excavations, there is disagreement: whether they are made in the Eastern Alpine sites of Austria according to southern samples or brought in finished form from the south. Even A. B. Meyer pointed out that the sickle-shaped fastener (brooch) with magnificent long pendants described by the Linz Museum was born far from Hallstatt; Görnes and other researchers believed that the famous Hallstatt iron dagger with a bronze grip ending in a ring made up of bird necks and dotted with geometric figures of naked men, located in the Vienna Museum of the Court, was brought to the north from the Italian south; Similarly, the often-quoted Strattweg badge belonging to the Graz collection, embellished with a relief image of sacrificing a deer, with very skinny, rough shapes of animals and people, most researchers attributed to the already familiar series of works of Italian art. But if the southern Hallstattzas, as well as the Wends, of the Illyrian tribe, there is no reason to assume that the manufacture of sieve (the ancient bronze vessels in the form of a bucket), which is best characterized by the Hallstatt culture, was known only to the Veneds; indeed, leaf bronze images found in the Hallstatt cemetery differ from those found in Italy by their special, highly barbaric character. Therefore, we, together with V. Gurlitt and others, think that sitsuly and belt badges of this kind were also made in Alpine countries under direct Greek-Eastern influence. Above, we have already mentioned the lid of the bronze vessel from Hallstatt. On the situation from Kuffarn, in Lower Austria, which is kept in the Vienna Court Museum, we see a band of images running only along its upper edge. It depicts a race contest that takes place in the presence of the judges, a fistfight for a prize (helmet) and a feast. The movements are extremely lively, but the forms, for all their clarity, are clumsy in many places. At first glance, it is clear that this art did not develop on its own, but was borrowed and even managed to “run wild”.

A situation from Vatsha (fig. 540), the Laibach Museum, first described by Hochstetter, is decorated with three bands of images placed one above the other: the lower one represents a frieze, depicting a lion devouring meat, and seven stone goats with curled stalks of plants in the mouth; the middle one is fistfight and feast, the top one is for people riding in chariots both on horseback and horses driven about. Male heads with large upturned noses and round eyes have a completely northern barbaric character.

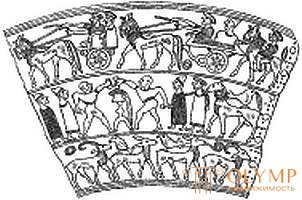

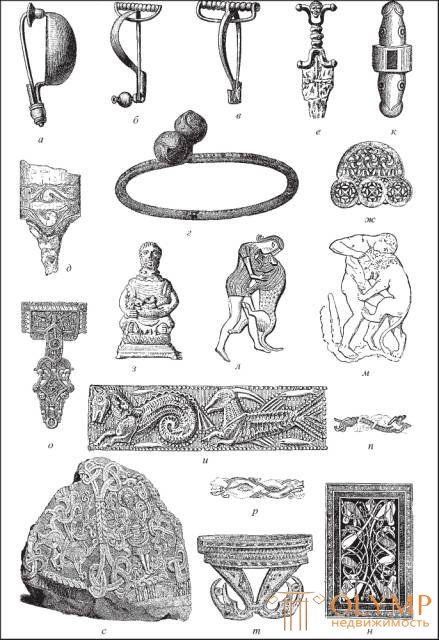

Our task is not to work to trace the multiple modifications of the Hallstatt brooches (Fig. 541, a - c ) - from their oldest forms, in the form of glasses and semicircles, in all their further transitions to the forms of hearts and crossbows to Laten fibula - or to compare bronze and the iron weapon of the Hallstatt culture in relation to its forms and ornamentation with the modern northern weapon of the Bronze Age. Equally, we cannot embark on a detailed study of the development of small bronze and clay figures of animals and people found in the graves of the Hallstatt culture. Awkward bronze or clay figurines - sometimes more or less geometrized, sometimes more naturalistic, among which the most typical are bulls with curved horns, horses with thin necks and straight legs, birds with a wide beak and human figures, with the exception of riders, are quite rare - they do not discover anything for us that we would not have found in the prehistoric times of Greece and Italy; we already met with handles in the form of the head of a bird or a horse, found in the bronze utensils of the Hallstatt culture, when we looked at the modern northern bronze age (see Fig. 28). The bulls on the Hallstatt bronze vat, in the Vienna Court Museum (Fig. 542), and bronze vessels in the form of birds from Hungary, in the same collection, are very characteristic; no less characteristic are bronze horsehead pendants from Yezerin, in the Museum of Sarajevo in Bosnia.

Fig. 542. Bronze tub of Hallstatt culture. According to Görnes

Fig. 543. Urn Hallstatt culture of Hemeleneenbarn. According to Görnes

The originality of the forms of Hallstatt culture we find mainly in clay plastic. We have already spoken about urns in the form of dwellings and facial (see fig. 29-31), which are not found in the actual spread of Hallstatt culture and for the most part belong to an earlier era. But the oldest Hallstatt culture owned remarkable clay products, originating from Edenburg, in Hungary. Some large black urns of the Vienna Court Museum are decorated with coarse triangular patterns, scratched before firing; on the neck, this pattern turns into quite distinct, although quite geometrical human figures in the ceremonial dress (Fig. 543). Their head is sometimes not marked at all, sometimes depicted as a circle or quadrilateral sitting on a long neck. Here, nothing resembles the Dipilonian style, but the figures are no less schematic and geometrized than in it.

Curious in their forms, symbolic "images of the moon" also come from Edenburg: clay sickles standing on their feet with vertically curved horns on thrones, turning into protomes of bulls and rams facing each other.

Plastic clay products found in the same mound near Hemeinledenburn, in Lower Austria, are also remarkable - the numerous figures of animals or people and urns stored in the Vienna court museum. On the upper edge of one of the urns, bird figures are seated, and on the surface of the vessel, where it begins to taper, Stsombati suggested plastic images of horsemen and standing shapeless human figures. Other urns have side handles in the form of arches ending in bull heads.

Finally, some features are represented by the polychrome clay plastic of the Hallstatt era. In the Austrian Hallstatt region itself, such plastics are rarely found. But from Vis, in Styria, occurs, for example, a fragment of an urn, decorated on a yellow background with red meanders. Polychrome vessels are more commonly found in the northern and western regions of Hallstatt culture. Vessels painted with red and black graphite paints with a white display in recessed ornaments of a rich geometric shape, are often found in Upper Bavaria, where Noak researched them, as well as in Baden; similar pots come across in Silesia. This can be seen in the museums of Karlsruhe and Breslau. L. Lindenshmit also recognized this polychrome Hallstatt German ceramics, and objections to his opinion seem to us not entirely convincing.

When looking at the Hallstatt ornamentation, it turns out to be impossible to recognize the character of unity. Everywhere we see in her differences depending on the locality and time; at every step, native ornaments are joined to those brought in from the outside. Animal ornamentation plays a large role in products, it can be in the form of plastic heads of birds, horses and bulls. In some places in a flat ornament dominates a purely geometric shape, but in the form of patterns and lines larger than before, the size. Very often, as in the Bronze Age in the north, ornaments in the form of humps and warts displace geometric forms. Straight lines everywhere join rounded, twisted, bent in an arc; everywhere there are hanging semicircles and stripes of wavy lines that are far from conforming to the concept of a geometric style. If we take some forms, such as, for example, rows of intertwined spirals, as a legacy of Mycenaean ornamentation, the question arises: why are there no other essential features of Mycenaean art in Hallstatt's ornamentation? However, in some forms of this ornamentation it is impossible to deny with certainty the strong influence of Oriental art, especially the ancient Greek of the time in which it had an Oriental character; but only occasionally it is possible to clearly distinguish what exactly penetrated here by a direct route from the southeast and which is carried in a roundabout way through the south and southwest. One can only notice everywhere along with the subtlety of the leaf bronze from which the utensils are made, some striving for a lively, complete, strong play of lines and an effort to adapt the forms borrowed from outside to local needs and taste.

Fig. 544. Belt plaque found in one of the graves of Kobani. According to virhov

This influence is clearly evident in the Fettersfeld gold finds, among which are the gold metal plates, luxuriously ornamented with animal motifs, kept in the Berlin Antiquarium. They were found in Lausitz and represent scattered remnants of the Scythian-early Greek art colonies along the shores of the Black Sea. Other writers considered them Scythian-Gothic works of the time of the resettlement of peoples; but adornments in the ranks of animals and images of the struggle between animals indicate their connection with Caucasian belt patches. They probably belong to the sixth century before and. e. It is difficult to give them a proper place in the general course of historical development, as it is generally difficult to determine the time of origin of almost all South Russian and Siberian antiquities. The Russian archaeologist Kondakov attributed the most ancient of the things found in Koban only to the first centuries of our era, but the opinion of this scholar may be disputed; however, he is undoubtedly right in recognizing as the works of the era of the migration of peoples later products stored in the Siberian Branch of the St. Petersburg Hermitage Museum, the amazing badges of penetration work with coarse relief figures of fantastic animals. Only the future will shed light on the development and influence of the language of the art forms of countries stretching from the mountain ranges of Asia to the depths of European Russia.

В североевропейском и среднеевропейском искусстве, следовавшем за гальштатской культурой, не всегда легко различить друг от друга элементы галльские, германские, скифские и славянские.

Племенные особенности в художественных работах этого цикла отражались гораздо менее заметно, чем общность условий жизни. О языческом северном зодчестве этого периода времени не может быть речи уже потому, что в валах и стенах, уцелевших от городов и укреплений, нет ничего художественного, а собственно строения, которые тогда почти везде были деревянными, совсем не сохранились. От крупной скульптуры, в которой религия галлов и германцев нисколько не нуждалась, дошли до нас только обломки. Живописи в собственном смысле слова это языческое искусство не знало. Оно производило преимущественно предметы так называемого малого искусства – художественной ремесленности и орнаментики.

За гальштатской культурой, доходящей до 300 г. до н. э., последовала в Европе латенская, которая в 100 г. н. e. уступила свое место римскому провинциальному искусству. Это последнее господствовало с 100 до 350 г. н. e. То, что явилось между 350 и 500 гг. n э., принято называть искусством времени переселения народов; произведения же, созданные между 500 и 750 гг. n э., принято относить во Франции и Германии к искусству эпохи Меровингов, в Скандинавии – к искусству позднейшей железной эпохи, за которым следовали в языческие времена на севере искусство викингов, на востоке Европы – искусство языческой Венгрии и искусство венедов. Эпоха викингов и венедов оканчивается лишь в XI в. n e. Конец этой художественной ступени наступает с введением христианства, что, однако, происходит в разные времена, отдаленные одно от другого целыми столетиями.

Искусство латенской культуры примыкает непосредственно к позднейшей гальштатской. Латен – местность, по которой со времени исследований Ф. Келлера и Ф. Гросса названа эта ступень культуры, так как здесь найдены первые, и притом образцовые, ее памятники, представляет собой отмель на Невшательском озере, близ деревни Марен. Основателями и первоначальными носителями латенской культуры были кельты, галлы в Швейцарии, во Франции и на Верхнем Рейне. Но культура эта, обойдя большой дугой собственно гальштатскую область, отвоевала себе германский Север, Англию, крайний Восток Европы и Верхнюю Италию, откуда исходили, по крайней мере, некоторые из ее проявлений. На западе Центральной Европы она подготовила почву для римского провинциального искусства, а в других местах – для искусства германской эпохи переселения народов. В искусстве латенской культуры так же мало самобытности и единства, как и в гальштатской; возникнув главным образом из смеси южных и восточных элементов, переработанных в местном духе, латенское искусство, вместе взятое, представляет, однако, больше единства, чем гальштатское.

In contrast to the Hallstatt culture of the first iron epoch, the Latenta culture arose during the times of a fully developed iron epoch. But we can speak about her art only with great limitations. The Gauls, who lived in the cities, were a practical and at the same time warlike people. Iron weapons and tools were their main products, which they, as a rule, did not decorate, and if there were any decorations, they were very modest. Even gold and bronze products differ from them more in the expediency of the basic forms than in the artistic character of the decoration. In this decoration, thin tin forms of Hallstatt art give way to a more complete, massive, profiled more strongly. Open bronze bracelets are often at the ends of the buttons in the form of a ball or calyx (see. Fig. 541, g). A brooch with the head of an animal in some localities belongs to the early Latinian culture. The developed form of the latent fibula is characterized by a double head with a spiral spring and a bent nest for a pin. Bronze chains sometimes end in a crochet in the shape of an animal's head.

Fig. 545. Bronze statuette of a warrior of the Laten culture. According to Görnes

In metal ornamentation , end-to-end work that is open on all sides acquires independent significance; in products of this kind, as can be seen on bronze III century BC. Oe., found in the graves of Champagne (W), the latent ornamentation reaches full development. Sometimes the incised lines of the ornament communicate with colored shine through a “bloody glass alloy”; pieces of coral and artificial colored pastes were also set in bronze. A different kind of play of colors was distinguished by blue and yellow glass handcuffs and amber beads.

Pottery art has not made progress except that it began to use the rotating circle.

The coins of the Laten culture represent the imitation of the Greek, Macedonian and Massalioto. At first, it is still possible to distinguish by what samples they are made, but then they are covered with the image of curls.

Among the Laten antiquities there are many small bronze and terracotta animal figures. Among them a boar is prominent, the Gallic "totem", whose image is also on the coins, there is also no lack of human figures. A small bronze figure of a warrior, originating from Idrija, on the Austrian coast, was recognized by Görnes as the best of the works of the late plastic arts (Fig. 545). Apart from a head that is too large, the shape of this figurine, for all the archaic stiffness, is rather clean and clear.

In spite of all the elements that make up the late Latin art, it still has its own face, and the role it played as an intermediary link between the forms of classical antiquity and the forms of the Christian middle ages gives it the right to a certain kind of value in world history of art. . But this value was acquired by him only because it skillfully processed all foreign things that flowed to him from the outside, in a distinctive style, which was by no means devoid of taste.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)