The rule of the Mongol-Tatar dynasty of the Yuan continued in the Heavenly Empire for a little more than one century. China has retained enough vitality to fully return to its national traditions. They were embodied in Gong Wu, the son of an ordinary worker who became the founder of the powerful and famous Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The first half of the era of this dynasty was especially flourishing at times in the arts and sciences. The XV century in China, as well as in Europe, is a period of their revival and further development. True, Chinese architecture from this time, apparently, has not made significant progress. But it is from it that especially many buildings survived in China, and it is in them that we find the most characteristic features of Chinese architecture. By 1421, the Temple of Heaven, which consists mainly of open terraces, dates back to 1425 - a temple dedicated to the memory of Emperor Yuan Lo in Beijing, with two roofs placed one above the other; by 1428-1478 - the restructuring of the vast imperial temple of Ta-Hüeg-si, near Beijing. This temple thanks to the photograph and description of Heinrich Hildebrand is known in construction for the best of all Chinese architectural monuments. Some parts of this structure are located symmetrically on a quadrangular space, in a shady park on the side of a mountain, next to each other. Four temples are located one behind the other on the middle axis of this space, stretching from west to east. And here, in all the individual buildings, the aforementioned “motive of an open wooden colonnade dominates, the spans of which are closed — though only later — by masonry between the individual pillars.” These pillars, on which the bases and capitals are only marked with paints, consist of solid wood trunks. On the marble balustrades of the temple terraces, next to the Indian tailed ornaments, real and distorted meanders of in-depth work are highlighted.

In the 15th century, stone gates were also built leading to the graves of the Ming dynasty and having five spans and five roofs (see fig. 580); at the same time, massive bells with bells in Beijing and the famous Nanking Porcelain Tower (see fig. 588) were built, from the ruins of which a well-glazed porcelain tile with yellow leafy ornaments was found, which is located in the Dresden porcelain collection.

The sculpture of the Ming Dynasty also received a new push forward. In the figures of people and animals the size of more than life, placed on the road to the tombs of Minov, there is some desire for nobility and solemnity; but the routine and dryness of their performance clearly show that attempts in this direction were for Chinese people in vain labor; all later statues of gods and relief images on the arches of the gates, on temples and towers confirm that understanding the language of forms of monumental plastics was alien to the Chinese.

Almost the same should be said about painting . No matter how extensive were the scrolls with paintings of famous Chinese painters, designated for hanging on the walls, no matter how much clarity and grace within the Chinese style these images reveal, this style, which we sometimes imitate in posters and billboards, can be called rather artistic, artisanal and decorative, than strictly picturesque. Chinese painting and Chinese art industry, in which the further development of Chinese art was mainly expressed, always went hand in hand.

The period of multilateral and magnificent flourishing was for Chinese painting in particular the first half of the dominion of the Ming dynasty. The painters of that time were distinguished not so much by originality as by their full possession of technical means and the field of images in which they had to show their skills. The greatest individuality is characterized by small pictures of the nature of artists Chien Chu (Chien-ch-tien) and Pi-wen Wen-tsina (Pien-king-chao). The most versatile and outstanding masters of this era are T'ang-Yin (T'ang-Liuyu), Chu Ying (She-chow), Tai-Tsin, Siou Won, Lin Leang and Wu Wei. The most famous of them is Fr. Geert called T'ang-Yin, who died in 1523, a contemporary of Raphael Urbinsky. His hand belongs to the picture in the Grassi Museum in Leipzig, in which the goddess of the sky was neatly painted in bright, clear colors with the girl behind her, hovering on a dragon (fig. 594). In the collection of Geert in Munich there is a copy of a painting by the same artist, depicting the Amazon Mu Lang, clothed in the armor of his sick father and entering his military service instead.

In the second half of the Ming Dynasty, painting gradually lost its former freshness, naturalness and spontaneity. At this time, the drawing is made more fictional, more soulless, more mannered; Reception of the letter becomes more timid, "sleek" and routine. Artists are specializing more and more. The dominant painting is inanimate nature, depicting branches of flowering plants, flowers, birds and butterflies. The best masters in this section are Lu Ki, Wang-i-pung and Chow-che-wang. Yang Li Peng owned the painting "Birds and Peony" (Fig. 595), which is in the collection of the British Museum.

The times of the Ming dynasty were brilliant at times of Chinese porcelain production. Under this dynasty, the dressing of porcelain became a real national art of the Chinese, which they undoubtedly invented and in which, no doubt, no other people surpassed them. The manufacture of plastic gods, people and animals on a small scale was constantly improved simultaneously with the improvement of the production of vessels. From the point of view of art history, decorations of porcelain vases are particularly important, sometimes embossed, but more often painted with paints. According to the character of the then painting, and here the ornamentation consists mainly of flowers, birds and butterflies. Its main elements are peonies, chrysanthemums, magnolias, lotus flowers, leaves and branches of the blossoming mummy, branches of the blossoming peach and cherry trees, but most often bamboo-loved by the Chinese. Plane stylization performed masterfully, but without pedantry. From the world of animals, in addition to birds and insects, fish, crayfish and small amphibians, which are interspersed with plants, are especially often taken; there are also in decorations on large vases unprecedented symbolic animals that we talked about. Figures of gods and people, scenes from everyday life, from legends, short stories and works of poetry, as well as images of historical events and real landscapes, appear only gradually on vases of a certain kind. Once achieved in this respect, to the extent permitted by the means of performance, has not been lost. Since in the subsequent time, imitations of porcelain products were made even with imperial brands (niengao), it is necessary to have a very familiar eye in order to distinguish real old porcelain from later fakes.

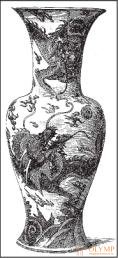

Researchers such as Du Sartel, Grandidier and Bushel, together with Chinese experts, recognize the period from 1426 to 652 as the classical era of Chinese porcelain production. For the first years of this period, vessels are typical, on which flowers, animal figures or symbolic images are painted with blue paint on a white background before watering. The vase of this period (fig. 596) is in the collection of Du Sartel in Paris. Soon the copper paint joins the blue paint. The best works of this period also include vases with embossed purple images against a turquoise background and white vases Tien-ne.

Fig. 594. T'ang-yin. Goddess on a dragon among the clouds. From the original

Fig. 595. Yang Li Pen. Birds and Peony. Painting. According to Anderson

Fig. 596. Chinese vase. From the collection of Du Sartel. By du sartel

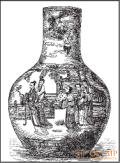

The second period of porcelain production during the Ming Dynasty is called the name of Emperor Ching-goa. This period lasts from 1465 to 1522, and if you combine it with the period of Kia-Tsing, then until 1579. An important innovation in this period was the use, along with coloring in blue on a white background, "five" or as the Chinese say, "many" paints, which, after applying them to porcelain, were lightly roasted. Grandidier believed that the beginnings of this method of painting porcelain existed even under Siu-en-te and that it was improved upon by Ching-goy. Thanks to this innovation for painting on the vases, the open space opened up, and she began to depict in greater size and better both human figures and landscapes, began to convey history and compete with poetry. The development of the forms went hand in hand with the invention of usable dyes. In fig. 597 vase, located in the Bertel collection in Paris, belongs to this period.

Fig. 597. Chinese vase. From the collection of Bertele. By du sartel

Fig. 598. Chinese vase. From the collection of Borelli. By du sartel

The last period, from 1573 to the end of the Ming dynasty, is similar to the previous one, named after the first emperor Wang Li who reigned in it. White vases with blue coloring now give way to a motley. Green paint to such an extent prevails in the multicolor coloring of the vessels of this time that the most beloved ones are called the "green family". Curly images or landscapes, which occasionally, as in the previous period, were placed in the form of framed pictures among floral ornaments, now began to fill, especially in the form of a continuous strip, the entire neck or surface of a vase. A model of such ornamentation can serve as a vase from the Borelli collection in Paris (fig. 598).

In Europe, Chinese porcelain vases of the Ming dynasty can be seen mainly in private French and English collections. Remarkable examples of this kind of works are also found in the British and South Kensington museums in London, as well as in the Berlin Museum of Art and Industry. In America, the most notable is the collection of such vases, which belonged to Walter in Baltimore and is excellently described by Bushel.

The Ming dynasty was replaced in 1644 by the reigning Tatar dynasty of Tsing, or Manju. Under her, the Chinese got a new look: they were forced to shave their heads in Tatar and wear a braid. In the spiritual respect, they approached decline, although Tatar sovereigns as quickly as their predecessors assimilated Chinese culture. From this time on, Christian missionaries began to preach the religion of love in China. European influence, now repressed, permissible, but never related to the most intimate national, was reflected in many aspects of Chinese spiritual life and art. However, this influence was by no means manifested in those works of art that the Chinese performed on their own initiative and for themselves, but, on the one hand, manifested themselves in the attempts of some French Jesuitists of the 18th century that had never succeeded in teaching the European perspective and chiaroscuro or shade they have Limoges enamel painting, and on the other hand, in the ingenuity of Chinese porcelain manufacturers, who, as before, worked for Persian taste in the Persian style, and for Siamese in Siamese, so The company, working for export trade, sufficiently adapted to European requirements.

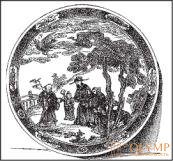

Fig. 600. Chinese plate. From the collection of Du Sartel. By du sartel

Chinese painting on silk or paper gradually fell into decay too. Countless guides, containing the rules and instructions regarding all the details of drawing and painting, freed Chinese artists from the labor of inventing and observing themselves. Technique alone was of some interest, and indeed, it stood, one might say, at an unattainable height until the end of the 18th century. Confidence and delicacy of the pattern sometimes make us forget the mannerism and superficiality of the image mode. From the middle of the XVII century. until the end of the 18th century, there were many artists in China who enjoyed notable fame; It goes without saying that their works were preserved in large numbers and made available to European collectors. For him, it is often made up in Europe a very mistaken opinion about all Chinese painting.

Fig. 599. White porcelain figure of the goddess Guanyin. From the original

The most famous painters of the religious Buddhist plots were: Tong-tai-chuan, who lived in the second half of the XVII century, King-nong and Loping in the XVIII century. In the field of landscape painting, Mei-Ven-ting, Wang-mu, Chang-cao, Giang-mu-che and Chen-pu-shu follow each other throughout this period. Skillful craftsmen depicting flowers and birds were Jun-shu-ping, nicknamed Cheng-shu (1633-1690), Li-fang-ing and Chen-shu-piao. Geert in Munich owned wonderful sketches of flowers that belonged to the first of these masters and his adopted daughter, Jun-ping.

Fig. 601. Lev Fo. Purple chinese porcelain figure. From the original

Fig. 602. Chinese porcelain plate. From the Messagère collection. By du sartel

In the same way, in all branches of applied art, the Chinese achieved the greatest success during the last third of the XVIIth and the whole XVIIIth century. At least under the emperors of Kansi (1662-1722), Jung-ching (1726-1736), and Qianlong (1736-1795), purely Chinese art differed, simultaneously with the desire to please overseas demands, which were not surpassed by any other people in the manufacture of bronze products decorated with colored cellular enamel, in fine works and especially in porcelain production. The most brilliant sometimes applied art in China, especially porcelain, the best experts until recently considered the reign of Kangxi. First of all, the production of fine white porcelain was revived, from which not only utensils and vessels were made, but also statues of Buddha, the goddess Guanyin (fig. 599) and saints, such as those with which the Dresden collection is rich. Then they achieved the high perfection of the so-called "green family" vases. On vases of this category, decorated with flowers, birds, butterflies, placed with great taste, besides the prevailing green color scheme, there are bright rust-red and a few blue, yellow and purple tones. As a sample of such products, you can point to a plate from the Du Sartel collection in Paris (fig. 600). Green vases with large images on a historical or religious theme were especially popular until in 1677 they were banned by an imperial edict. At the same time, the production of vases of the "red family" began. Along with them, vessels with blue drawings on a white background and porcelain objects completely covered with the most luxurious colors were made again: celadon, fiery-orange, turquoise with an admixture of violet tones — works of peculiar beauty. Figures of lions (fig. 601) or Fo dogs were made mainly of this kind. The most magnificent examples of such works can be seen in the Dresden collection, most of the objects of which belong to the Kangxi era in general. In the reign of Qianlong, the "red family" of porcelain vases and plates comes to the fore, and next to it is a thin, elegant, almost entirely single glaze "egg-shell porcelain". In fig. 602 - a plate of the "red family", located in the collection of the Messager in Paris. The two varieties of porcelain products just mentioned have been made for a long time, but only now they have reached perfection. However, the excessive abundance of their ornamentation heralds the onset of decline, which continued throughout the nineteenth century.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)